Last year, Pew Research Center conducted its second U.S. religious knowledge survey, designed to gauge Americans’ familiarity with a variety of religion-related facts. (The first was conducted in 2010.) This time, we also included a few questions aimed at measuring how much Americans know about the Holocaust, resulting in this report.

The new data is based on a survey of 10,971 U.S. adults conducted in February 2019. Most of the people surveyed (10,429) were members of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel. An additional 542 respondents were sampled from the Ipsos KnowledgePanel – all of them Jewish, Mormon or Hispanic Protestant, to bolster the samples for these subgroups. Both the online survey panels used as a basis for this study recruited panelists by phone or mail via random sampling to ensure that nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. Recruiting panelists this way gives us confidence that any sample can represent the whole population (watch our Methods 101 explainer on random sampling).

To further ensure that each survey reflects a balanced cross-section of the nation, the data are weighted to match the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology and the methodology for this report.

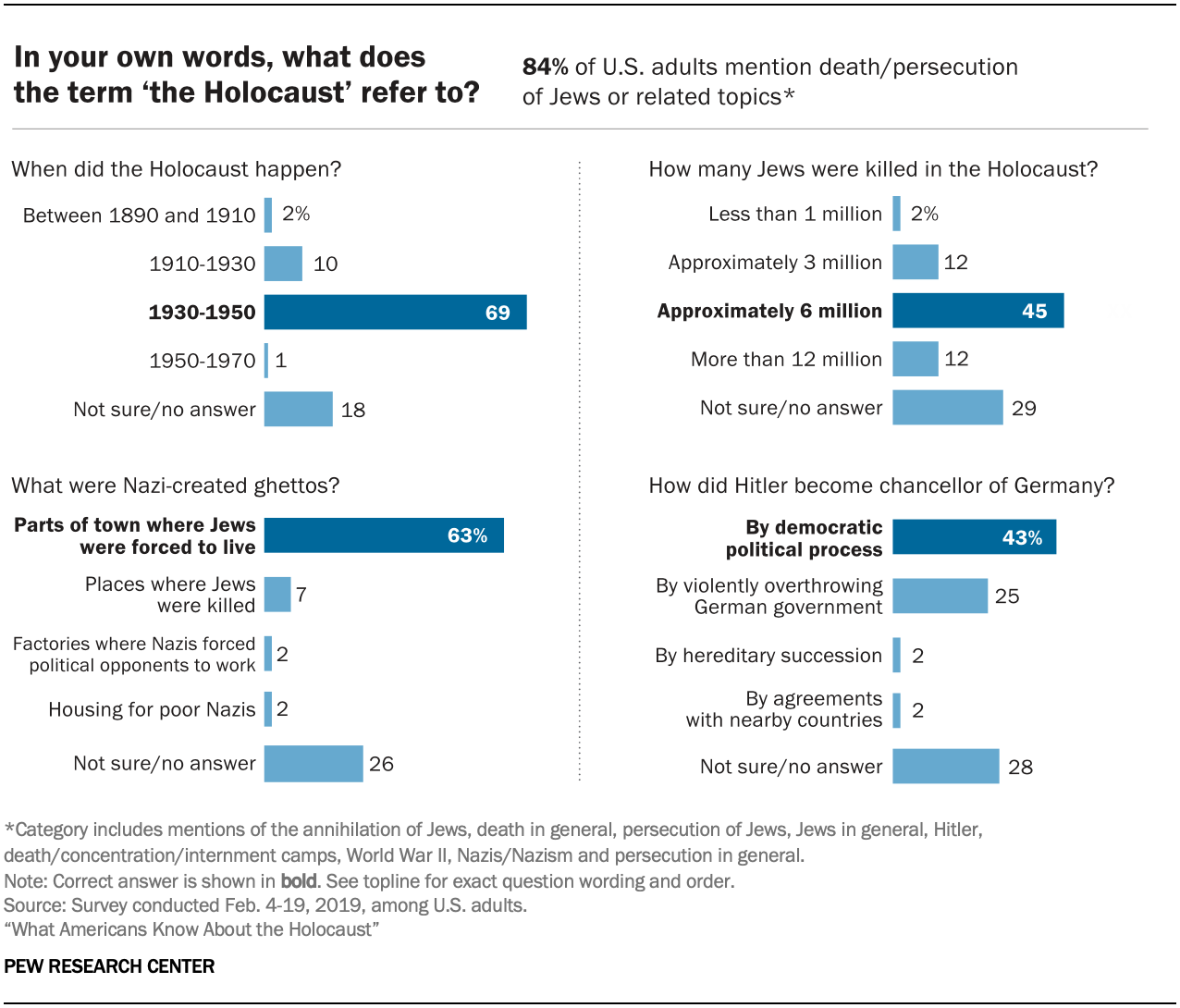

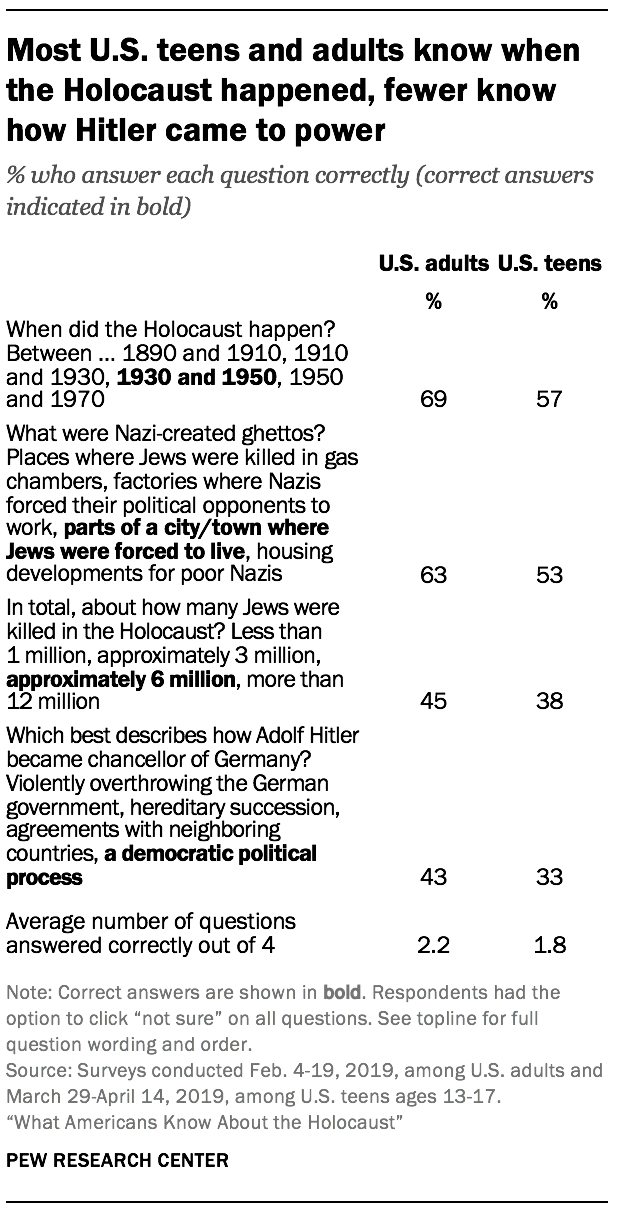

Most U.S. adults know what the Holocaust was and approximately when it happened, but fewer than half can correctly answer multiple-choice questions about the number of Jews who were murdered or the way Adolf Hitler came to power, according to a new Pew Research Center survey.

When asked to describe in their own words what the Holocaust was, more than eight-in-ten Americans mention the attempted annihilation of the Jewish people or other related topics, such as concentration or death camps, Hitler, or the Nazis. Seven-in-ten know that the Holocaust happened between 1930 and 1950. And close to two-thirds know that Nazi-created ghettos were parts of a city or town where Jews were forced to live.

Fewer than half of Americans (43%), however, know that Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany through a democratic political process. And a similar share (45%) know that approximately 6 million Jews were killed in the Holocaust. Nearly three-in-ten Americans say they are not sure how many Jews died during the Holocaust, while one-in-ten overestimate the death toll, and 15% say that 3 million or fewer Jews were killed.

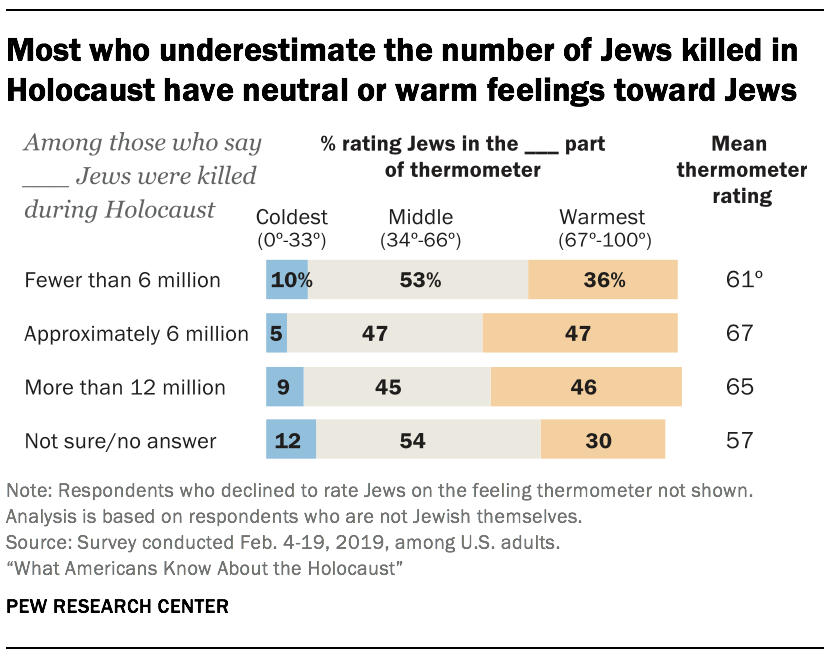

This raises an important question: Are those who underestimate the death toll simply uninformed, or are they Holocaust deniers – people with anti-Semitic views who “claim that the Holocaust was invented or exaggerated by Jews as part of a plot to advance Jewish interests”?1

This raises an important question: Are those who underestimate the death toll simply uninformed, or are they Holocaust deniers – people with anti-Semitic views who “claim that the Holocaust was invented or exaggerated by Jews as part of a plot to advance Jewish interests”?1

While the survey cannot answer this question directly, the data suggests that relatively few people in this group express strongly negative feelings toward Jews. On a “feeling thermometer” designed to gauge sentiments toward a variety of groups, nine-in-ten non-Jewish respondents who underestimate the Holocaust’s death toll express neutralor warm feelings toward Jews, while just one-in-ten give Jews a cold rating. Similar shares express cold feelings toward Jews among those who overestimate the number of Holocaust deaths (9%) and among those who say they do not know how many Jews died in the Holocaust or decline to answer the question (12%).

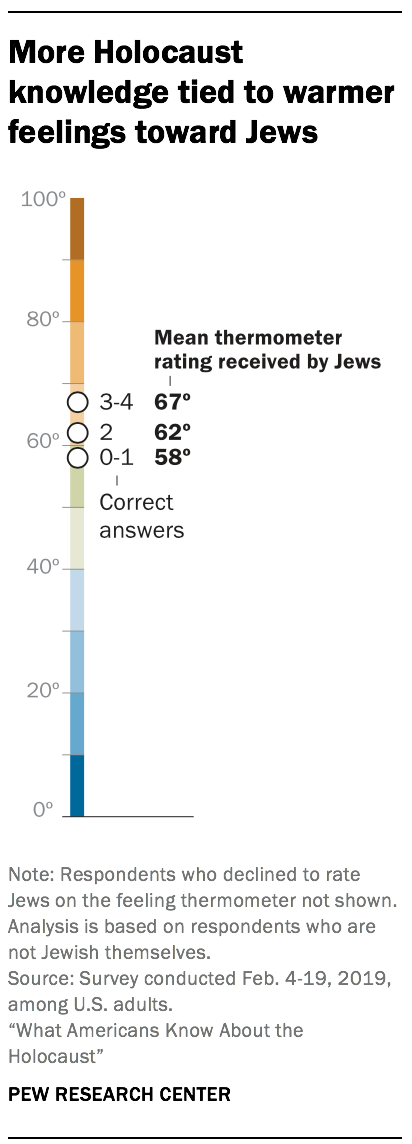

That said, respondents who get more questions right also tend to express warmer feelings toward Jews. For example, non-Jews who correctly answer at least three of the four multiple-choice questions about the Holocaust rate Jews at a relatively warm 67 degrees on the feeling thermometer, on average. By comparison, non-Jews who correctly answer one question or less (including those who get none right) rate their feelings toward Jews at 58 degrees, on average.

That said, respondents who get more questions right also tend to express warmer feelings toward Jews. For example, non-Jews who correctly answer at least three of the four multiple-choice questions about the Holocaust rate Jews at a relatively warm 67 degrees on the feeling thermometer, on average. By comparison, non-Jews who correctly answer one question or less (including those who get none right) rate their feelings toward Jews at 58 degrees, on average.

These are among the key findings of a survey conducted online Feb. 4 to 19, 2019, among 10,971 respondents. The study was conducted mostly among members of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (a nationally representative panel of randomly selected U.S. adults recruited from landline and cellphone random-digit-dial surveys and an address-based survey), supplemented by interviews with members of the Ipsos KnowledgePanel. The margin of sampling error for the full sample is plus or minus 1.5 percentage points.

A previously published report on this survey explored the public’s answers to 32 knowledge questions about a wide range of religious topics, including the Bible and Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, atheism and agnosticism, and religion and public life. In addition to the 32 questions about religious topics, the survey included five factual questions to test knowledge of the Holocaust: one open-ended question and four multiple-choice questions.

The four multiple-choice questions also were included in a separate survey of approximately 1,800 U.S. teens (ages 13 to 17). Overall, the teens display lower levels of knowledge about the Holocaust than their elders do. Like the adults, however, teens fare best on the questions about when the Holocaust occurred and what ghettos were. About half or more of teens answer those questions correctly. By comparison, 38% of teens know that approximately 6 million Jews perished in the Holocaust, and just one-third know that Hitler came to power through a democratic process. See here for details.

The Holocaust knowledge questions were designed to measure some basic facts about the Holocaust, including when it happened and who it involved. However, the questions were not meant to include all of the most essential facts about the Holocaust.

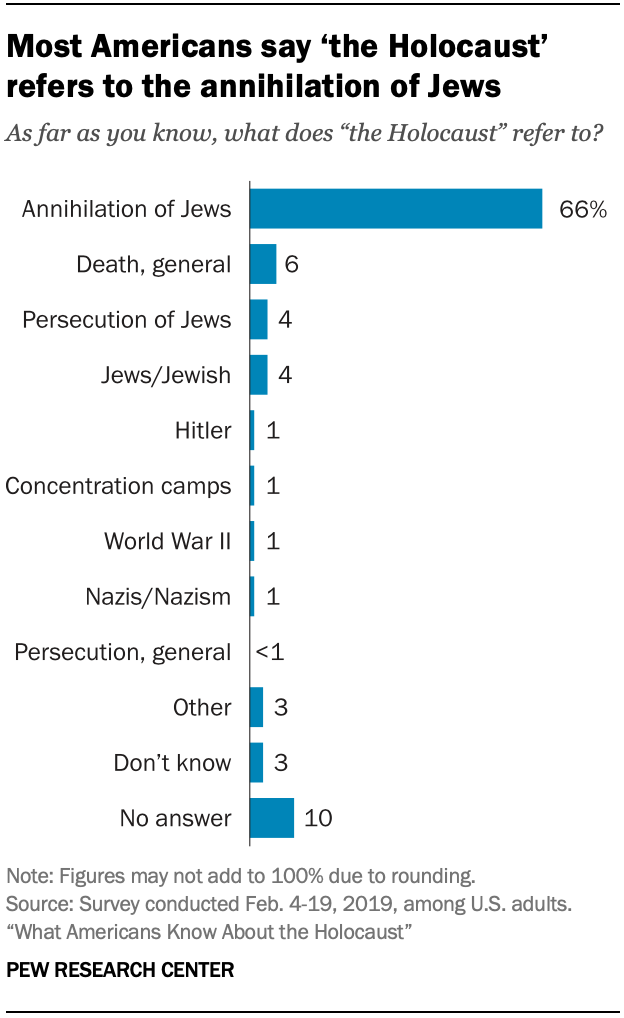

The open-ended question asked: “As far as you know, what does ‘the Holocaust’ refer to?” and invited respondents to write their answers in their own words. In response, two-thirds say the Holocaust refers to the attempted annihilation of the Jewish people, or words to that effect, mentioning the mass murder of Jews.

The open-ended question asked: “As far as you know, what does ‘the Holocaust’ refer to?” and invited respondents to write their answers in their own words. In response, two-thirds say the Holocaust refers to the attempted annihilation of the Jewish people, or words to that effect, mentioning the mass murder of Jews.

An additional 18% mention concepts that are more loosely associated with the Holocaust, including the general idea of death (6%), the persecution (but not murder) of Jews (4%), or just something about Jewish people (4%). This group also includes some respondents who reference Hitler, concentration camps, World War II, Nazis or persecution in general without mentioning Jews specifically.2

Just 3% of Americans mention something else, and an equal share say they don’t know. One-in-ten decline to answer the question.

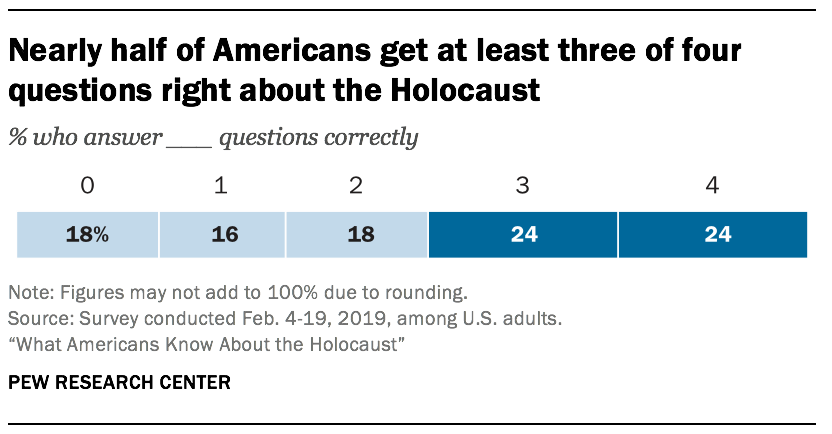

Overall, the average respondent correctly answers about half (2.2) of the four multiple-choice Holocaust knowledge questions. Nearly half of Americans get at least three questions right, including one-quarter who correctly answer all four questions (24%). Roughly one-in-five respondents do not answer any of the Holocaust knowledge questions correctly, mainly because they say they are “not sure” about the answers to the questions.

Overall, the average respondent correctly answers about half (2.2) of the four multiple-choice Holocaust knowledge questions. Nearly half of Americans get at least three questions right, including one-quarter who correctly answer all four questions (24%). Roughly one-in-five respondents do not answer any of the Holocaust knowledge questions correctly, mainly because they say they are “not sure” about the answers to the questions.

Jews, atheists and agnostics get more questions right about the Holocaust

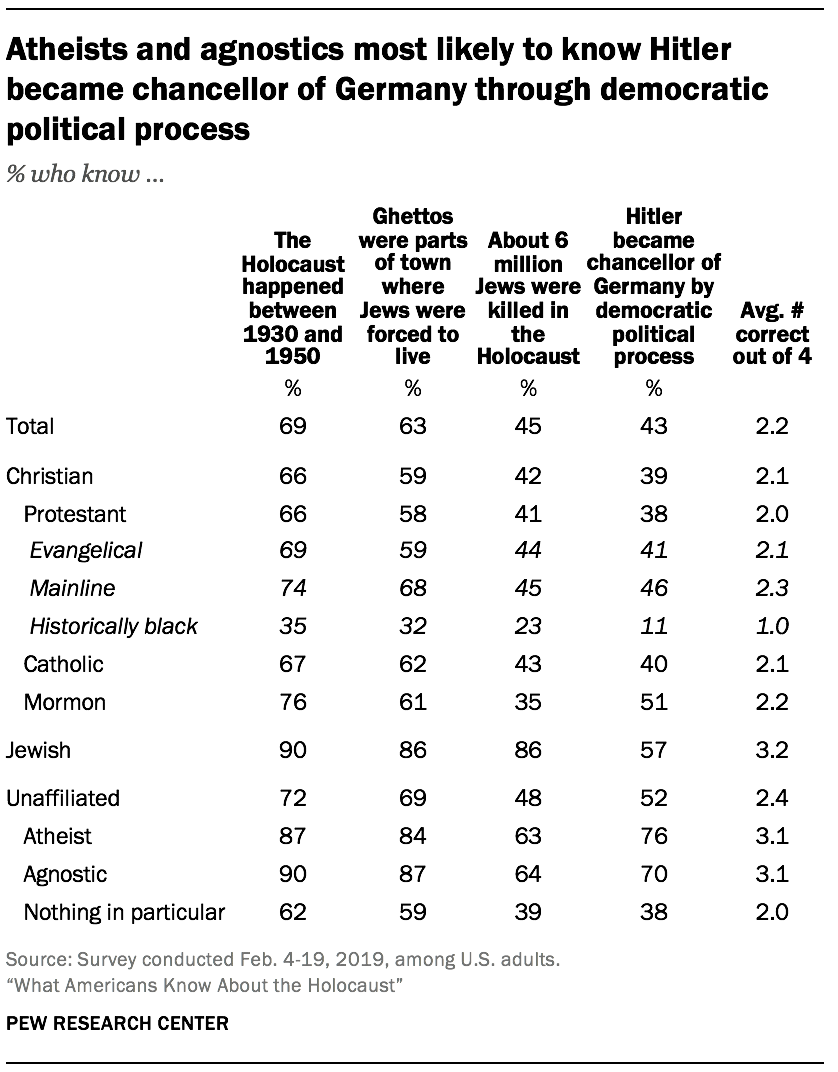

Jews (3.2), atheists (3.1) and agnostics (3.1) get the most questions right about the Holocaust, answering an average of at least three of the four questions correctly. (These groups also rank among those with the highest levels of overall religious knowledge.) Mainline Protestants, Mormons, Catholics, evangelical Protestants and Americans who describe their religion as “nothing in particular” correctly answer about half of the questions, while members of the historically black Protestant tradition get one out of four right, on average.

Jews (3.2), atheists (3.1) and agnostics (3.1) get the most questions right about the Holocaust, answering an average of at least three of the four questions correctly. (These groups also rank among those with the highest levels of overall religious knowledge.) Mainline Protestants, Mormons, Catholics, evangelical Protestants and Americans who describe their religion as “nothing in particular” correctly answer about half of the questions, while members of the historically black Protestant tradition get one out of four right, on average.

Nearly nine-in-ten U.S. Jews (90%), agnostics (90%) and atheists (87%) know that the Holocaust happened between 1930 and 1950. Similarly, an overwhelming majority of agnostics (87%), Jews (86%) and atheists (84%) know that ghettos were parts of a town or city where Jews were forced to live.

U.S. Jews are more likely than atheists and agnostics to know how many Jews were killed in the Holocaust. Nearly nine-in-ten Jews know that about 6 million Jews were killed in the Holocaust, compared with two-thirds of agnostics (64%) and atheists (63%) who get this question right. By contrast, more atheists and agnostics than Jews correctly answer the question about how Hitler became chancellor of Germany: Three-quarters of atheists (76%) and seven-in-ten agnostics know Hitler became chancellor through a democratic political process, compared with 57% of Jews.

Education, visiting a Holocaust museum and knowing someone who is Jewish are strongly linked with Holocaust knowledge

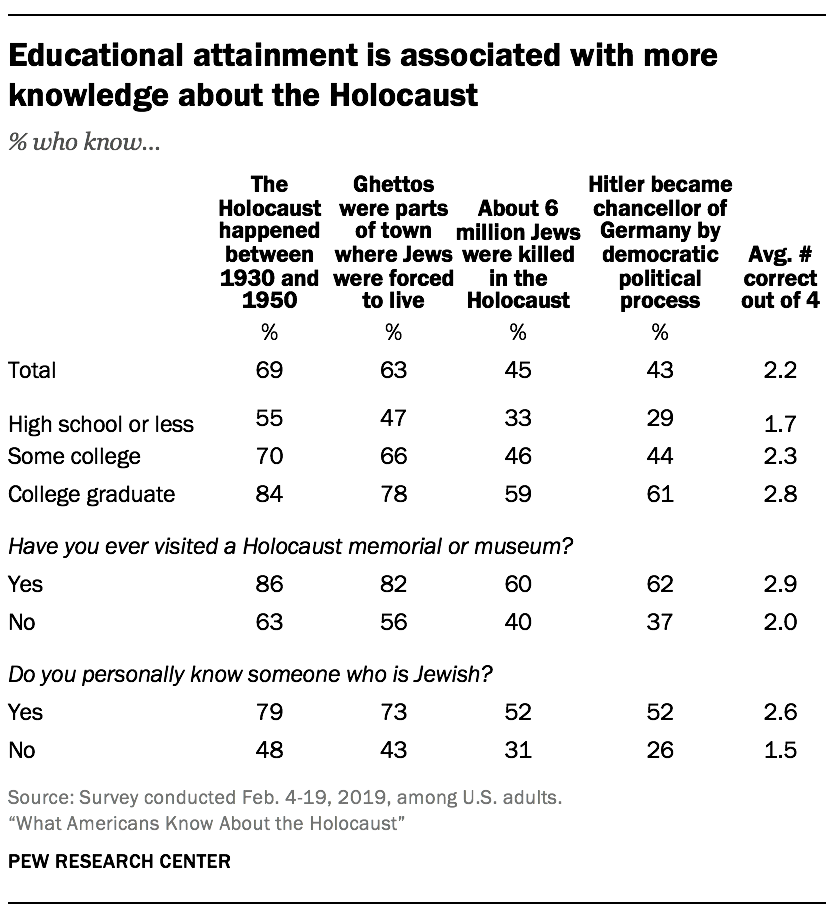

In addition to religious affiliation, several other factors are associated with how much Americans know about the Holocaust. For example, college graduates get an average of 2.8 out of the four multiple-choice questions right, while those whose formal education ended with high school correctly answer 1.7 questions.

In addition to religious affiliation, several other factors are associated with how much Americans know about the Holocaust. For example, college graduates get an average of 2.8 out of the four multiple-choice questions right, while those whose formal education ended with high school correctly answer 1.7 questions.

Another factor linked with how much Americans know about the Holocaust is whether respondents have ever visited a Holocaust memorial or museum. U.S. adults who say they have visited a Holocaust memorial or museum (27% of all respondents) correctly answer 2.9 questions right out of the four multiple-choice questions about the Holocaust. By comparison, those who have never visited a Holocaust memorial or museum answer 2.0 questions right, on average.

The survey included a question that asked respondents whether they personally know someone who is Jewish. Compared with those who say they do not know anyone who is Jewish, Americans who know a Jewish person answer about one additional question right, on average (2.6 vs. 1.5).

Older adults display slightly higher levels of Holocaust knowledge

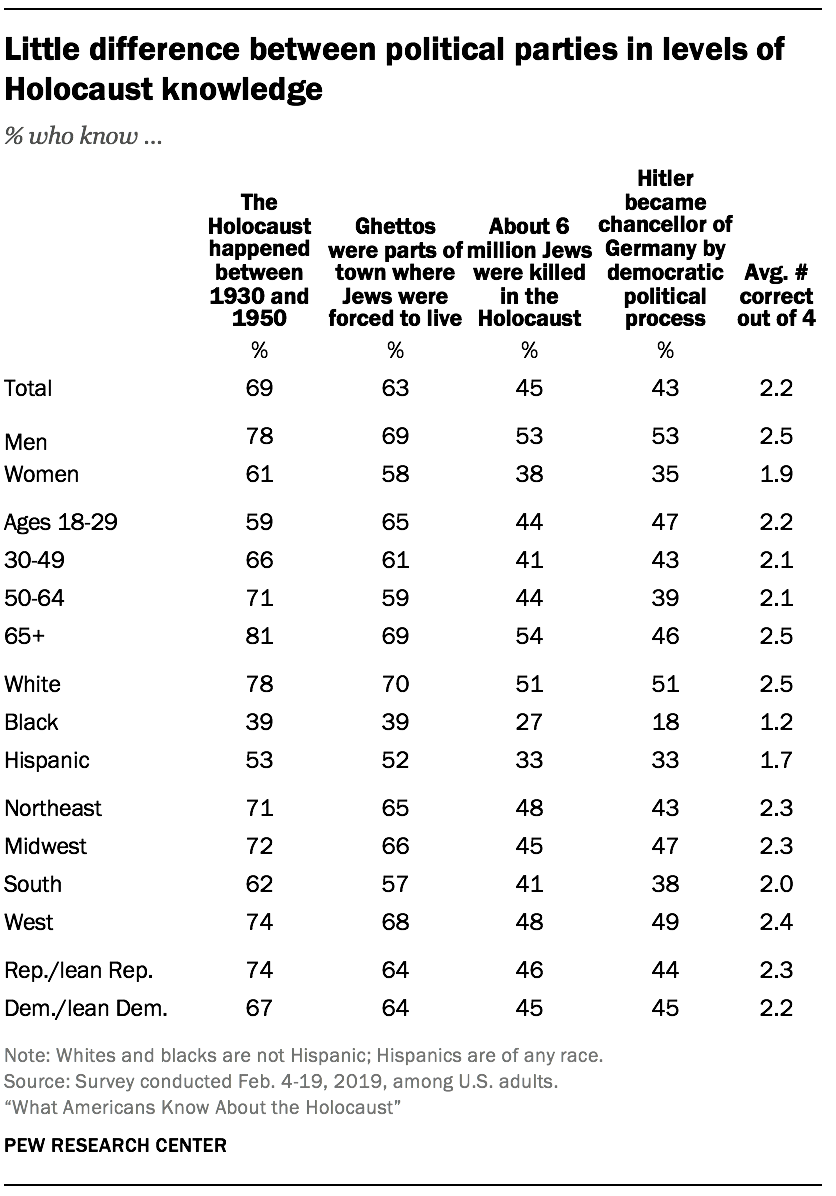

There are modest differences in levels of knowledge about the Holocaust based on gender, race and ethnicity, age, and region. For example, men correctly answer 2.5 out of four multiple-choice questions, on average, while women get 1.9 right.3 And white respondents get an average of 2.5 questions right, compared with 1.2 questions among black adults and 1.7 questions among Hispanics.

There are modest differences in levels of knowledge about the Holocaust based on gender, race and ethnicity, age, and region. For example, men correctly answer 2.5 out of four multiple-choice questions, on average, while women get 1.9 right.3 And white respondents get an average of 2.5 questions right, compared with 1.2 questions among black adults and 1.7 questions among Hispanics.

In addition, Americans ages 65 and older correctly answer an average of 2.5 questions about the Holocaust, compared with 2.2 right answers among those under the age of 65. And U.S. adults who live in the West, Northeast and Midwest perform slightly better than those who live in the South.

Politically, Republicans and those who lean toward the Republican Party (2.3) correctly answer about as many Holocaust knowledge questions as Democrats and Democratic leaners do (2.2).

U.S. teens’ levels of Holocaust knowledge similar to those of adults without post-secondary education

The four multiple-choice questions about the Holocaust also were included in a recent Pew Research Center survey of U.S. teens ages 13 to 17.

The four multiple-choice questions about the Holocaust also were included in a recent Pew Research Center survey of U.S. teens ages 13 to 17.

Like adults, more teens know when the Holocaust occurred (57%) and what Nazi-created ghettos were (53%) than know how many Jews were killed during the Holocaust (38%) or how Hitler became chancellor of Germany (33%).

On average, teens correctly answer slightly fewer questions than U.S. adults do (1.8 vs. 2.2, on average). This may reflect disparities in education. Among adults, those with a college degree correctly answer about one question more than those with a high school degree or less. Of course, teens between the ages of 13 and 17 have not yet had a chance to pursue post-secondary education. Overall, U.S. teens correctly answer about the same number of questions (1.8, on average) as adults whose formal education ended with high school (1.7).

However, one difference between teens and adults is the relationship between gender and Holocaust knowledge. While adult men answer slightly more questions right than women, teen boys and girls correctly answer a similar number of questions about the Holocaust (1.8 each, on average).

Previous Holocaust knowledge surveys

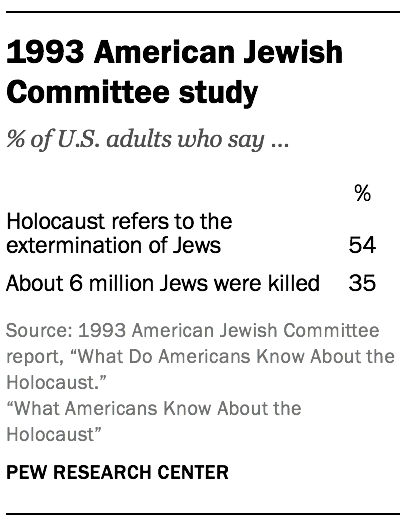

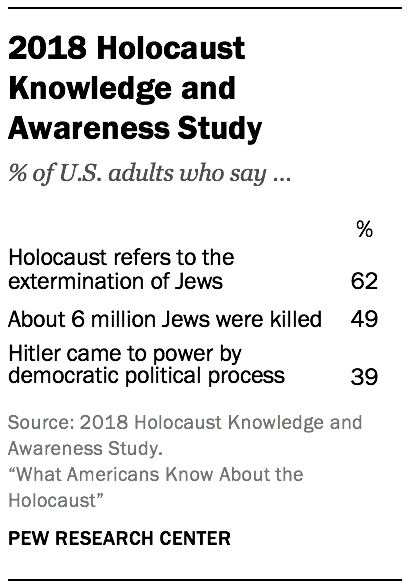

The 2019 Pew Research Center survey is not the first research conducted to assess how much American adults know about the Holocaust. In 1993, the American Jewish Committee (AJC) published the results of a study regarding what U.S. adults and students in the 10th, 11th and 12th grades knew about the Holocaust.4 And in 2018, the Holocaust Knowledge and Awareness Study, conducted by the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, asked American adults many of the same questions that were discussed in the 1993 report.

The 2019 Pew Research Center survey is not the first research conducted to assess how much American adults know about the Holocaust. In 1993, the American Jewish Committee (AJC) published the results of a study regarding what U.S. adults and students in the 10th, 11th and 12th grades knew about the Holocaust.4 And in 2018, the Holocaust Knowledge and Awareness Study, conducted by the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, asked American adults many of the same questions that were discussed in the 1993 report.

There are several important differences between Pew Research Center’s 2019 Holocaust knowledge questions and the other two surveys that make it so that they are not directly comparable (and thus unable to gauge whether levels of knowledge about the Holocaust have changed over time).

Even though some of the questions asked on the new survey are similar to those asked on previous surveys, these questions were not always asked in the exact same way. For example, all three surveys included a question asking approximately how many Jews were killed during the Holocaust. While the question wording was similar, Pew Research Center’s question included five response options listed from smallest to largest: “Less than 1 million,” “approximately 3 million,” “approximately 6 million,” “more than 12 million” or “not sure.” The AJC study and the Holocaust Knowledge and Awareness Study each included six response options listed from largest to smallest: “20 million,” “6 million,” “2 million,” “1 million,” “100,000” and “25,000.” (The AJC study included a “don’t know” option, while the Knowledge and Awareness Study included “other” and “not sure” options.) And while all three studies included an open-ended question asking respondents to describe in their own words what “the Holocaust” refers to, the responses were not necessarily coded using the same criteria.

Even though some of the questions asked on the new survey are similar to those asked on previous surveys, these questions were not always asked in the exact same way. For example, all three surveys included a question asking approximately how many Jews were killed during the Holocaust. While the question wording was similar, Pew Research Center’s question included five response options listed from smallest to largest: “Less than 1 million,” “approximately 3 million,” “approximately 6 million,” “more than 12 million” or “not sure.” The AJC study and the Holocaust Knowledge and Awareness Study each included six response options listed from largest to smallest: “20 million,” “6 million,” “2 million,” “1 million,” “100,000” and “25,000.” (The AJC study included a “don’t know” option, while the Knowledge and Awareness Study included “other” and “not sure” options.) And while all three studies included an open-ended question asking respondents to describe in their own words what “the Holocaust” refers to, the responses were not necessarily coded using the same criteria.

The respondents also took the surveys in different ways. The 2019 Pew Research Center survey was administered online on the American Trends Panel, a nationally representative panel of randomly selected U.S. adults. By contrast, the survey discussed in the 1993 AJC report was administered by interviewers in respondents’ homes. The 2018 Holocaust Knowledge and Awareness Study was administered mostly by interviewers over the phone, but also included some interviews administered online. Sometimes when the same question is asked in different modes, such as over the phone and online, there is a difference in results that is attributable to what survey methodologists call a mode effect. In other words, the presence of a live interviewer may encourage people to answer questions differently than they would if no one was observing their (self-recorded) responses.