Americans strongly support using gene editing techniques for people’s therapeutic needs. But, when it comes to their potential use to enhance human health over the course of a lifetime by reducing a baby’s risk of getting serious diseases or conditions, as many Americans think this would be a bad idea for society as say it would be a good idea. The public is also closely divided over whether they would want this for their own baby. As with previous Pew Research Center surveys on this topic, women and more religious Americans are less accepting of gene editing for this purpose.

Scientific advances in the use of CRISPR technology are expanding the possibilities for using gene editing. These techniques are currently in development for therapeutic needs. Clinical trial data suggests that gene therapy can be effective in treating some heritable blood disorders such as sickle cell anemia. Other trials have shown promise for treatment of life-threatening rare diseases.

There are a large number of potential applications of gene editing techniques for humans.2 One includes the possibility of using gene editing to prevent, or greatly lower the probability, of developing serious disease. If such applications become widespread it would potentially change the trajectory of human health, greatly reducing the prevalence of serious disease.

The current survey asked respondents to consider one possible use of gene editing techniques: changing the DNA of embryos before a baby is born in order to greatly reduce the baby’s risk of developing serious diseases or health conditions over their lifetime.

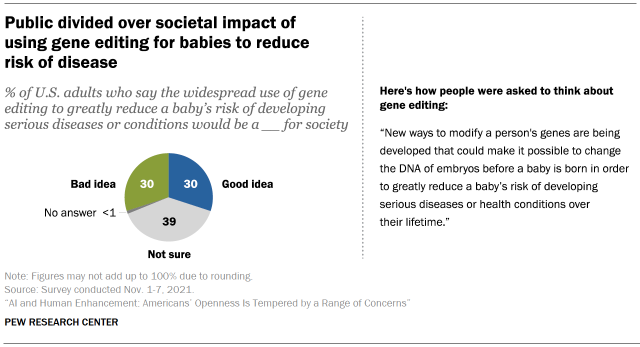

Among U.S. adults, equal shares (30% each) say the widespread use of gene editing to greatly reduce a baby’s risk of developing serious diseases or health conditions over their lifetime would be a good idea or bad idea for society. About four-in-ten (39%) are not sure how they feel about using gene editing for this purpose.

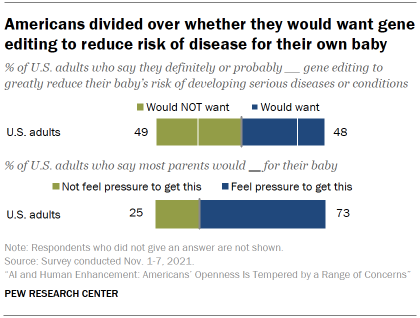

Americans are about evenly divided over whether they would want to use gene editing in this way for their own baby, if it were available to them. Overall, 48% say they would definitely or probably want this for their own baby; a similar share (49%) say they would not.

Parents of a minor-age child are a bit more hesitant: 42% say they would want this kind of gene editing for their own baby, while 55% say they would not. (See details in Appendix.)

Although Americans are closely divided over whether they themselves would want gene editing to reduce the risk of disease for their own baby, a majority thinks that most parents would feel pressure to get this type of gene editing. Nearly three-quarters (73%) think most parents would feel pressure to get gene editing to reduce their baby’s risk of developing disease if its use becomes widespread. Far fewer (25%) think most parents would not feel pressure to use gene editing for their baby.

A 2016 Center survey also focused on the idea of using gene editing to enhance health by greatly reducing a baby’s chance of developing serious diseases over their lifetime. Americans were also closely divided over whether or not they would want this kind of gene editing for their baby (48% would and 50% would not). However, the current survey and past Center surveys on American’s views of gene editing in babies have found large differences in views depending on the intended purpose of the genetic modification.

Concern about potential widespread use of gene editing to reduce a baby’s health risk is stronger among those with high religious commitment

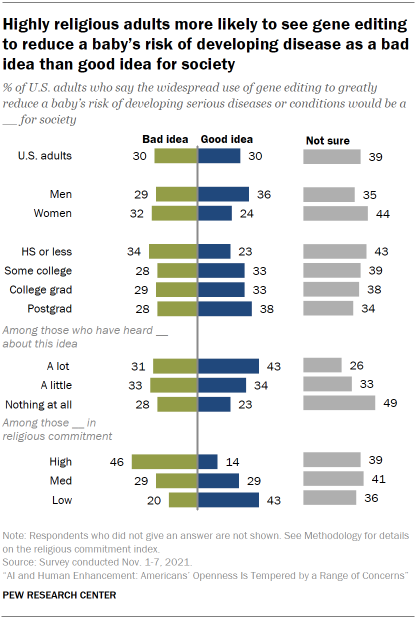

One of the largest gaps in views of gene editing to reduce a baby’s risk of developing serious disease is between those with higher and lower levels of religious commitment. Those with higher levels of religious commitment (a three-item index based on the importance of religion in their life and their frequency of religious service attendance and prayer) are much more likely to call the widespread use of gene editing in this way a bad idea than a good idea for society (46% to 14%). By contrast, those with low levels of religious commitment are about twice as likely to say it’s a good idea for society than to say it’s a bad idea (43% to 20%). Between 36% and 41% of those across levels of religious commitment say they aren’t sure about their views.

On balance, men are more likely to call the use of gene editing to reduce the risk of disease in babies a good (36%) rather than a bad idea (29%). Women tilt in the other direction, with more saying the widespread use of gene editing for this purpose would be a bad idea than a good one (32% to 24%).

Among those with at least some college experience, views are slightly more positive than negative about the use of this technology. People with a high school diploma or less education are more negative than positive about the implications for society from the widespread use of gene editing in this way.

Just 8% of U.S. adults say they have heard or read a lot about using gene editing to greatly reduce a baby’s risk of developing serious diseases or conditions over their lifetime, while 47% say they have heard a little and 44% say they have heard nothing at all about this.

People more familiar with the concept of gene editing for babies to reduce the risk of serious diseases or health conditions during their lifetime are more likely to say it is a good idea than bad idea for society (43% to 31%), while about a quarter say they’re not sure (26%). Among those who hadn’t heard about this idea prior to the survey, 28% think the use of gene editing in babies would be a bad idea for society, compared with 23% who think it would be a good idea; nearly half of this group (49%) say they aren’t sure.

Americans foresee both positive and negative implications from widespread use of gene editing to enhance human health

While gene editing techniques hold the promise of reducing the risk of serious disease over a person’s lifetime, the public is not entirely convinced that this would lead to a higher quality of life for people.

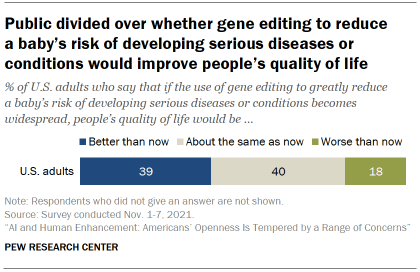

Overall, 39% of U.S. adults think the widespread use of gene editing to greatly reduce a baby’s risk of developing serious diseases or health conditions over their lifetime would lead to a better quality of life for people. However, 40% say quality of life for people would be about the same as now if this technology were widely used, and 18% say it would be worse.

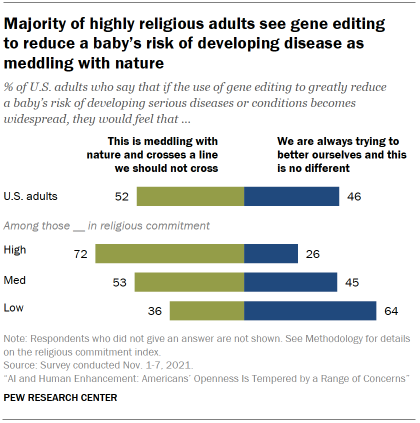

Further, about half of Americans (52%) say that “this idea is meddling with nature and crosses a line we should not cross.” By contrast, 46% say their views are better described by the statement “as humans, we are always trying to better ourselves and this idea is no different.”

A majority of those high in religious commitment (72%) consider this use of gene editing to be inappropriate, crossing a line we should not cross. By contrast, a majority of adults with low levels of religious commitment (64%) take the opposing view and describe this use of gene editing as no different than other efforts to better ourselves.

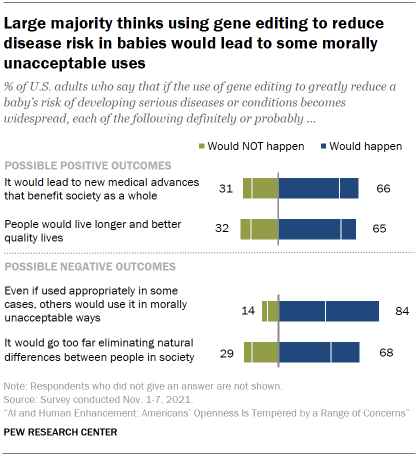

Asked to think about a future where gene editing to reduce the risk of babies developing serious diseases or health conditions is widespread, the public sees both positive and negative impacts as likely to happen. But one negative outcome is seen as particularly likely: the use of these techniques in ways that are morally unacceptable.

Overall, 84% think that even if gene editing is used appropriately in some cases, others would definitely or probably use these techniques in ways that are morally unacceptable.

Nearly seven-in-ten (68%) say these gene editing techniques would definitely or probably go too far eliminating natural differences between people in society.

At the same time, 66% say the development of these techniques would definitely or probably pave the way for new medical advances that benefit society as a whole, and 65% say these techniques would likely help people live longer and better-quality lives.

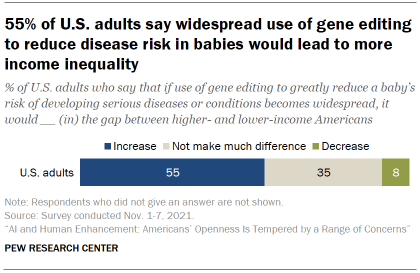

In thinking about access to these techniques, 55% of U.S. adults say that if the use of gene editing to reduce a baby’s risk of developing a serious disease during their lifetime becomes widespread, the gap between higher- and lower-income Americans would increase. About a third (35%) say the widespread use of this technology would not make much difference in the gap between higher- and lower-income Americans; 8% say it would decrease this gap.

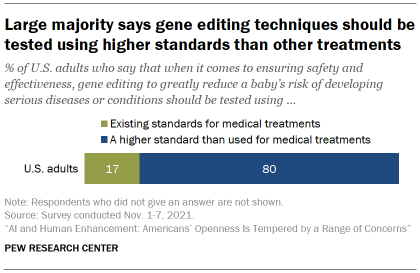

Majority backs higher standard for testing use of gene editing in babies, major role for medical scientists in setting standards

In line with concerns about the possible misuse of gene editing, a large majority (80%) of Americans say that gene editing techniques to greatly reduce a baby’s risk of serious diseases or conditions should be tested using a higher standard than those used for other medical treatments to ensure their safety and effectiveness. Only 17% say gene editing should be tested using existing standards for medical treatments.

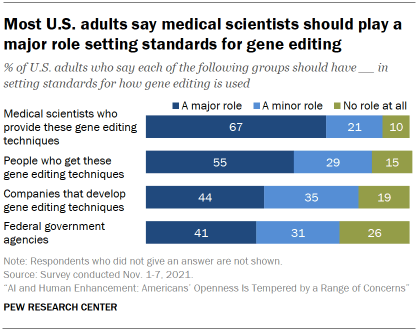

When asked who should be responsible for setting standards regarding the use of gene editing, two-thirds of Americans (67%) believe that medical scientists should play a major role, while another 21% say they should play a minor role.

Over half (55%) say the people who get these gene modifications should play a major role in setting the standards for how they are used; 29% think they should play a minor role.

Fewer than half say the companies that develop gene editing techniques (44%) and federal government agencies (41%) should have major roles in setting standards. However, majorities of Americans say both of these groups should play at least a minor role in setting standards for how gene editing techniques are used.

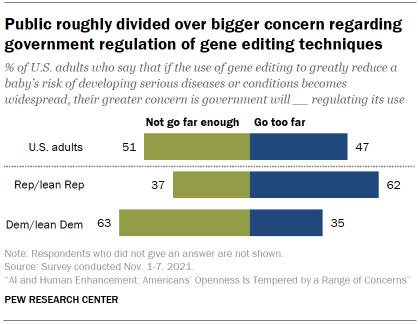

Americans are closely divided when it comes to their greater concern about government regulation in this area. In all, 51% say that if this use of gene editing becomes widespread, their greater concern is government will not go far enough regulating its use. Nearly as many (47%) take the opposite view and say their greater concern is that government regulation will go too far.

Democrats and Republicans differ widely on this question, consistent with their broader views on government regulation. A majority of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents (62%) say that if gene editing to reduce a baby’s risk of developing a serious disease or condition becomes widespread, their greater concern is that government will go too far in regulating the use of this technology. Among Democrats and Democratic leaners, 63% say their greater concern is that government regulation will not go far enough.

Consent, control and heritability matter in thinking about the potential use of gene editing to reduce the risk of developing disease

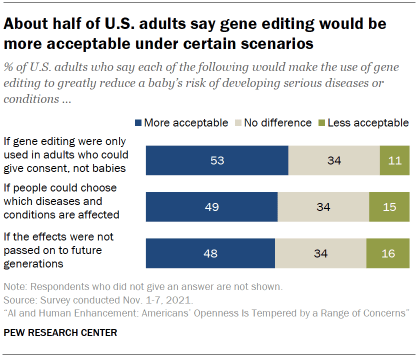

Overall, 53% of U.S. adults say the use of gene editing would be more acceptable to them if it were only used in adults who could consent to the procedure, rather than for babies; 34% say this wouldn’t make a difference in their view and 11% say it would make the use of gene editing less acceptable to them.

About half or more of both those who say they would and would not want to use gene editing for their own baby say the idea of adult consent for this use of gene editing would make it more acceptable to them.

Roughly half (49%) of Americans also say the use of gene editing to reduce disease risk would be more acceptable to them if people could choose which diseases and conditions are affected. A similar share, 48%, say it would be more acceptable to them if the effects were limited to the person receiving the treatment and not passed on to future generations, a key concern among genetic experts when it comes to the societal and ethical implications of gene editing in babies.

About seven-in-ten Americans favor the use of gene editing to treat serious diseases

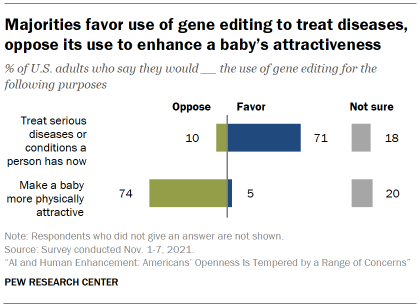

When asked to consider some other possible uses for gene editing (beyond use on babies to prevent the future risk of disease) the public is broadly supportive of using gene editing to treat conditions a person already has, but they are broadly opposed to using it to make a baby more attractive.

About seven-in-ten Americans (71%) say they would favor the use of gene editing to treat serious diseases or health conditions that a person currently has. Just 10% say they would oppose gene therapy, and 18% say they’re not sure.

Gene therapy aims to treat disease by correcting an underlying genetic problem. It is in use or in an experimental development phase for a range of diseases including immune deficiencies and cancer.

A 57% majority of those with high levels of religious commitment on a three-item index favor the use of gene editing to treat a current disease or health condition, as do large majorities of those with medium (71%) and low (83%) levels of religious commitment.

By contrast, a large majority (74%) in the U.S. say they would oppose using gene editing to change a baby’s physical characteristics to make them more attractive. Only 5% would favor this (20% say they’re not sure).

These findings are broadly in line with a 2019-2020 Center survey which found majorities in the U.S. and many other places surveyed thought the use of gene editing in babies to make a baby more intelligent would be taking technology too far but that gene editing for treating a baby’s serious disease or health condition would be an appropriate use of the technology.