Majorities across global publics accept evolution; religion factors prominently in belief

This report examines public perceptions of biotechnology, evolution and the relationship between science and religion. Data in this report come from a survey conducted in 20 publics from October 2019 to March 2020 across Europe, Russia, the Americas and the Asia-Pacific region. Surveys were conducted by face-to-face interview in Russia, Poland, the Czech Republic, India and Brazil. In all other places, the surveys were conducted by telephone. All surveys were conducted with representative samples of adults ages 18 and older in each survey public.

Here are the questions used for the report, along with responses, and the survey methodology.

Global publics take a cautious stance toward scientific research on gene editing, according to an international survey from Pew Research Center. Yet most adult publics (people ages 18 and older) draw distinctions when it comes to specific applications of human gene editing, including showing wide support for therapeutic uses.

The findings come amid a period of rapid development in biotechnology in which new tools, such as CRISPR gene-editing technology, have extended the possibilities of science, raising the need for scientists, governments and people around the world to grapple with the accompanying social, ethical and legal considerations.

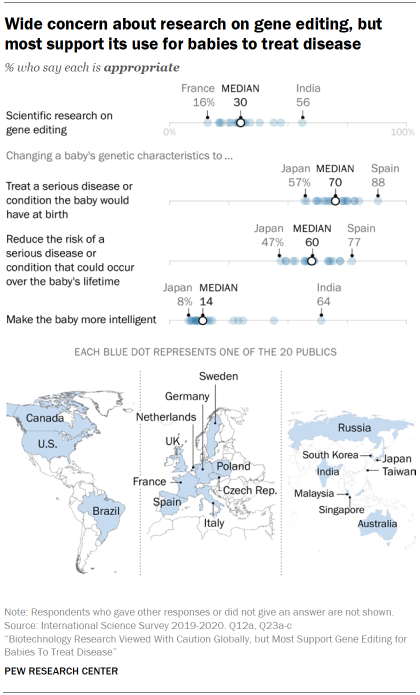

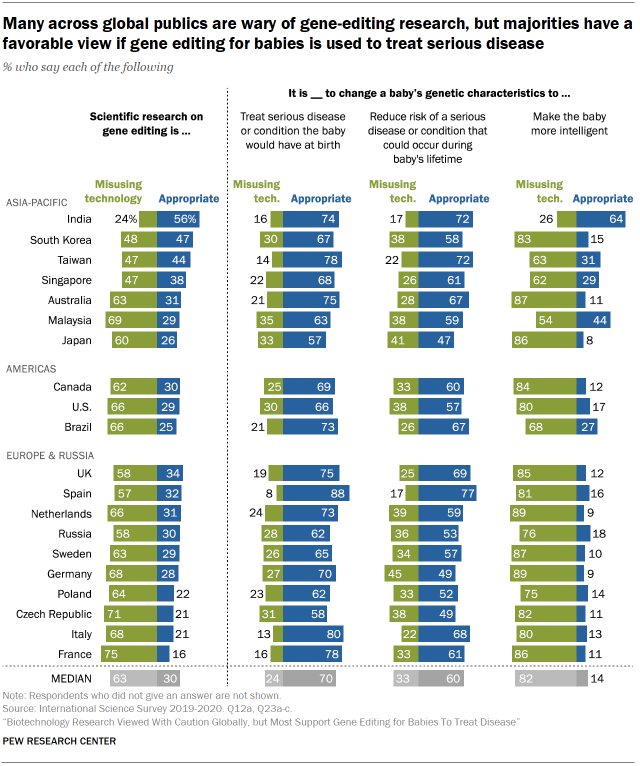

A 20-public median of 63% say scientific research on gene editing is a misuse – rather than an appropriate use – of technology, according to the survey fielded in publics across Europe, the Asia-Pacific region, the United States, Canada, Brazil and Russia.

However, views on specific instances where gene editing might be used highlight the complex and contextual nature of public attitudes. Majorities say it would be appropriate to change a baby’s genetic characteristics to treat a serious disease the baby would have at birth (median of 70%), and somewhat smaller shares, though still about half or more, say using these techniques to reduce the risk of a serious disease that could occur over the course of the baby’s lifetime would be appropriate (60%). But a median of just 14% say it would be appropriate to change a baby’s genetic characteristics to make the baby more intelligent. A far larger share (median of 82%) would consider this to be a misuse of technology.

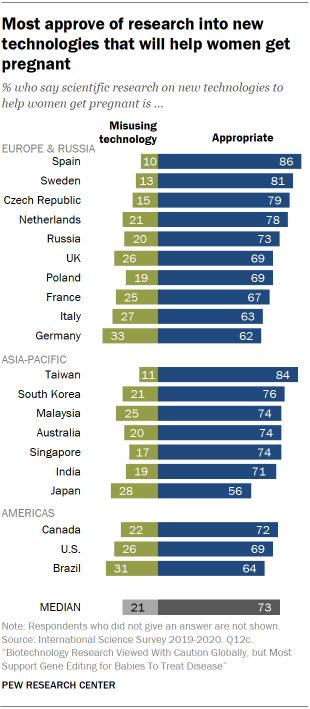

Global publics also draw distinctions between the areas of scientific research they view as appropriate and inappropriate. There is broad support across most places surveyed for scientific research on new technologies to help women get pregnant (a median of 73% view this as appropriate). But research on animal cloning is largely met with opposition, with a median of two-thirds (66%) considering scientific research on animal cloning to be a misuse of technology.

Religious beliefs tie with attitudes on many aspects of biotechnology across global publics but the impact of religion is far from uniform. For instance, Christians are often more wary than those who are religiously unaffiliated, especially in the West. In the U.S., about half as many Christians as religiously unaffiliated adults consider scientific research on gene editing to be an appropriate use of technology (21% vs. 47%). Similar gaps are seen in the Netherlands, the UK, Sweden and other publics across Western Europe.

But in India, a majority of adults (56%) view research on gene editing as appropriate – the highest level measured across places surveyed – and Hindus and Muslims there are equally likely to express this view. In Singapore – a country with a religiously diverse population –about half or more Christians, Hindus and Muslims see research on gene editing as a misuse of scientific technology. Buddhists and the religiously unaffiliated in Singapore are closely divided on this issue.

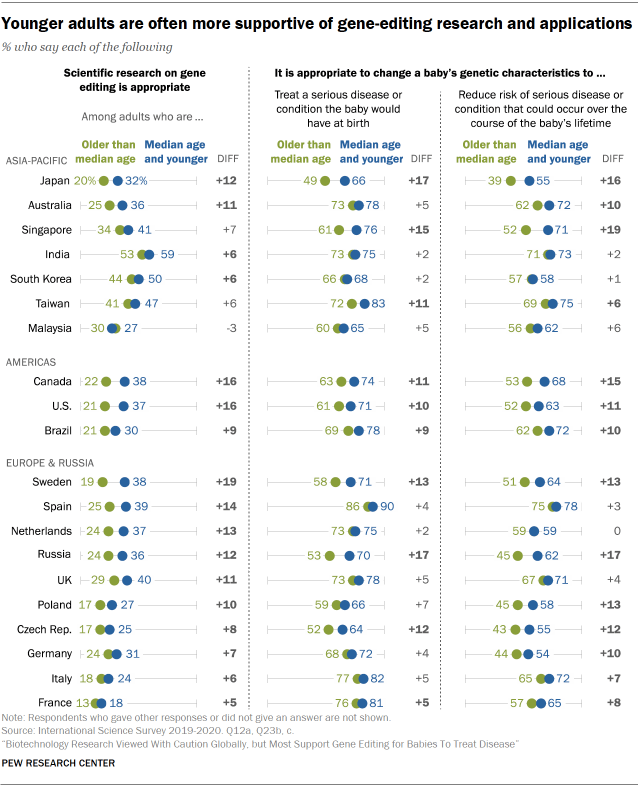

Age – rather than religion – has a more uniform relationship with views of biotechnology research and its applications across the 20 publics surveyed. In nearly all places surveyed, younger adults (those at or below the median age) are more likely than older adults to say that scientific research on gene editing is appropriate, though both groups often express general wariness. In Sweden, for instance, 38% of younger Swedes and half as many older Swedes (19%) view gene-editing research as an appropriate use of technology.

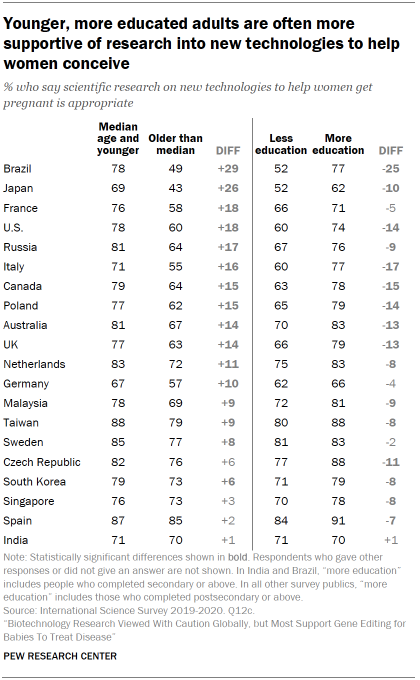

Younger adults are also more accepting than older adults of research on animal cloning and pregnancy technology across most places surveyed. There are similar age differences in views about potential uses of human gene-editing technologies.

The survey also looks at public beliefs about evolution, an area often seen as a point of friction between science and religion, particularly for followers of Abrahamic faiths such as Christianity or Islam.

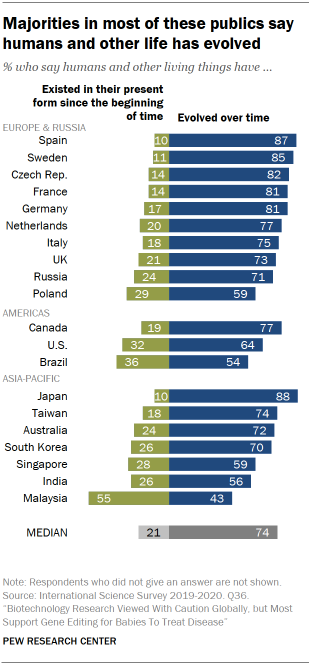

The survey finds broad acceptance of evolution across these publics. A median of 74% say humans and other living things have evolved, while a median of just 21% think humans and other living things have existed in their present form since the beginning of time.

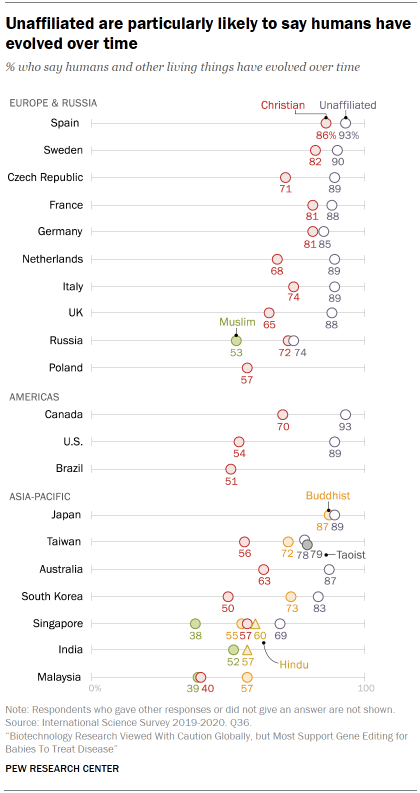

Beliefs about evolution are strongly linked with religious affiliation. Christians – especially those for whom religion is highly salient – are less accepting of the idea that humans and other living things have evolved over time. In Canada, for instance, 93% of religiously unaffiliated adults say humans and other living things have evolved over time compared with a smaller majority of all Christians (70%) and 49% of Christians who say religion is very important to them. In South Korea, half of Christians say that humans and other living things have evolved, compared with 73% of Buddhists and 83% of the religiously unaffiliated.

Muslims are also less accepting of evolution across the publics surveyed. About four-in-ten Muslims in Malaysia and Singapore say that humans and other living things have evolved. In India and Russia, it is roughly half.

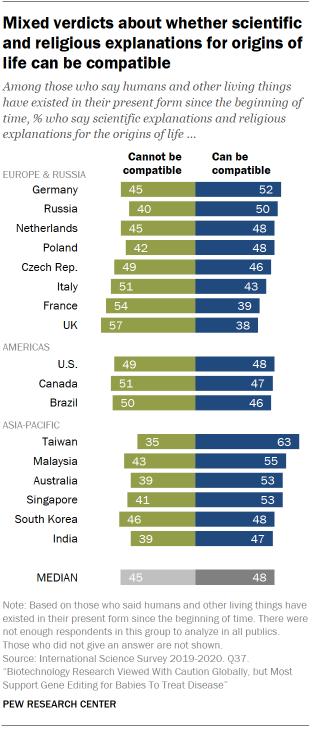

Those who believe that humans and other living things have existed in their present form since the beginning of time are generally of two minds about the potential for scientific and religious explanations to align. Among those who reject evolution, nearly equal shares across these publics say that scientific and religious explanations for the origins of life can be compatible as say they cannot. (Median of 48% to 45% across the 17 publics with a large enough sample for analysis.)

Despite such differences by religion, when people assess how often their own religious beliefs are at odds with science, majorities say that conflict rarely or never occurs (20-public median of 62%). A median of just 11% say their religious beliefs often conflict with science. Another 21% say this sometimes happens.

These are among the chief findings from the survey conducted among 20 publics with sizable or growing investments in scientific and technological development from across Europe (the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden and the UK), the Asia-Pacific region (Australia, India, Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan) as well as Russia, the U.S., Canada and Brazil.

See “Science and Scientists Held in High Esteem Across Global Publics” for more findings from this survey

Majorities across most of these publics are wary of gene-editing and animal cloning research; younger adults tend to be more receptive

The past quarter century has seen rapid developments in modern biotechnology, particularly from the discovery of more precise techniques for genome editing. Earlier this year, the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, awarded to Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier, called attention to the importance of advances in the field stemming from CRISPR gene-editing technology.

Public opinions about emerging developments in biotechnology are mixed, with majorities across most places surveyed expressing caution about doing scientific research on gene editing and animal cloning. But public reaction to using gene-editing techniques for babies is widely positive if the goal is aimed at the treatment of disease. And scientific research into pregnancy technologies is generally seen in an approving light.

Younger adults are generally more supportive than older adults of research in these areas of biotechnology. And religion is often connected with views about these topics, with Christians typically more wary than those who are religiously unaffiliated, particularly in the West.

Publics are generally cautious about research on gene editing, but are much more accepting if gene editing will be used for therapeutic purposes

Public views about scientific research on gene editing are more negative than positive. But the balance of opinion about using gene editing to change a baby’s genetic characteristics depends on how it will be used.

A median of 30% across the 20 publics say scientific research on gene editing to change people’s genetic characteristics is appropriate. Nearly two-thirds (median of 63%) – including majorities in all but a handful of publics surveyed – say such research is a misuse of technology. French adults are the most disapproving of research into gene editing. Just 16% in France say it is appropriate, while three-quarters say it’s a misuse of scientific technology. India stands out as the only place where a majority of adults (56%) consider gene-editing research to be appropriate.

People are more positive about gene-editing technologies if they’ll be used to treat illnesses a baby would have at birth. Majorities in all places surveyed (20-public median of 70%) describe using gene editing to treat a serious disease or condition a baby would have at birth as appropriate, while about one-quarter (median of 24%) say this would be a misuse of technology. Support for using gene editing for babies to treat disease is particularly strong in Spain, where 88% describe it as appropriate and just 8% say it is a misuse of technology.

People are also generally in favor of using human gene editing to reduce the risk of future health problems from occurring. A median of 60% say it is appropriate to use gene editing to reduce the risk of a serious disease a baby could develop over their lifetime, while 33% see this as a misuse of technology. About three-quarters of adults are positive about this application in Spain (77%), as are roughly seven-in-ten in India and Taiwan. Opinion is more narrowly divided in Germany, where 49% say this is appropriate while 45% say it is misusing technology. And in Japan, opinion divides 47% appropriate to 41% misusing technology.

In 2018, the use of CRISPR technology by Chinese scientists aimed at making babies genetically resistant to HIV led to widespread condemnation and concern in the international scientific community. Ethical concerns were driven in part by the unknown health implications from this type of human germline genome editing over time.

When survey respondents consider the possibility of using human gene editing to make a baby more intelligent, the answer from the general public is clear. A median of just 14% across the 20 publics say this would be acceptable; 82% say it would be misusing technology.

Similarly, in-depth interviews in Malaysia and Singapore found that when those interviewed –whether Muslim, Hindu or Buddhist – talked about their views of research on gene editing, many were positively disposed to the idea of using such techniques to treat serious disease. However, some interviewees raised concerns about other possible uses of gene editing, including a fear that people might try to westernize their children by creating babies with blond hair and blue eyes.

Younger adults tend to be more accepting of gene-editing research and its applications for babies than their elders

Across nearly all of the 20 publics surveyed, younger adults are more likely than older ones to say that scientific research on gene editing is appropriate. This age gap is largest in Sweden, where 38% of younger adults (those at the median age or younger), say this research is acceptable, compared to just 19% of older Swedes, a gap of 19 percentage points.

Younger adults also tend to be more accepting of using gene editing on babies to treat disease at birth and to reduce the risk of serious disease over a baby’s lifetime. Statistically significant differences by age occur in half or more of the publics surveyed. In Japan, for instance, a majority of younger adults say it’s acceptable to use gene editing to treat disease (66%), compared with about half (49%) of older adults.

Opinion about using gene editing to change a baby’s intelligence is generally negative across age groups, and there are few sizable differences between older and younger adults about this application of gene editing.

Religious differences sometimes play a sizeable role in opinion about gene editing

Adults who have no religious affiliation are often more supportive of gene-editing research than those who are religiously affiliated, particularly in Western countries with larger shares of Christians.

In 10 of the publics surveyed, unaffiliated people (including atheists, agnostics and people who say they are “nothing in particular”) are more likely than Christians to describe gene-editing research as an appropriate use of scientific technology. However, even among the unaffiliated, no more than about half see such research as appropriate.

In the U.S., for instance, nearly half of unaffiliated Americans (47%) say gene-editing research is acceptable, compared with 21% of Christians. Similarly, Christians are more disapproving of gene-editing research than the unaffiliated in the Netherlands, Canada, the UK, Australia, Sweden, Italy, Spain and Germany.

In the Czech Republic, Christians and religiously unaffiliated adults are more disapproving than approving of gene-editing research. In Russia, about half or more of the unaffiliated, Christians and Muslims say such research is misusing technology. (There are not enough unaffiliated respondents in Poland for separate analysis.)

India stands out as more positive about gene-editing research. Just over half of Hindus (57%) and Muslims (59%) see such research as appropriate. By contrast, both Muslims and Christians in Malaysia tend to be disapproving of such research.

Buddhists in Malaysia are more divided over the appropriateness of research on gene editing (44% to 47%), as are Buddhists in Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan. In Taiwan, Taoists are also closely divided, with 48% saying gene-editing research is appropriate and 45% saying this is misusing technology.

Religious groups are generally more accepting of changing a baby’s genetic characteristics in order to treat serious disease or to reduce the risk of serious disease over their lifetime. (See Appendix.) Most people, regardless of religious affiliation, think it would be a misuse of technology to use gene editing to increase a baby’s intelligence.

Religious salience also factors into people’s views on these issues. Those who are more religious, saying religion is very important in their lives, tend to be more disapproving of scientific research on gene editing. This pattern is seen in a number of countries with larger Christian populations, including the U.S., the UK, Canada, Australia, the Netherlands and Italy.

There are similar differences by religious salience in views about using gene editing for babies. For example, religiously affiliated adults in Australia who consider religion very important in their lives are less supportive of using gene editing to treat disease a baby would have at birth than those for whom religion is not too or not at all important (57% vs. 75%, respectively).

Men are more approving than women of gene-editing research in 12 of the 20 publics surveyed. However, gender differences fade when it comes to views about using gene editing for babies to treat disease at birth or reduce the risk of serious disease over their lifetime.

Public views about research on animal cloning are mostly negative

The balance of opinion about scientific research on animal cloning is much more negative than positive in most places surveyed.

In the nearly 25 years since cloning Dolly the sheep, cloning techniques have been used to create an exact genetic copy of an existing animal across more than 20 species, including livestock, dogs and primates.

Advocates see a number of benefits from animal cloning for biomedical research and agriculture. Others raise concerns about animal welfare and see drawbacks from animal cloning such as reducing the genetic diversity of the species.

Across the 20 publics, a median of 27% say animal cloning research is an appropriate use of technology, while more than double that figure (median of 66%) say such research is a misuse of scientific technology.

Disapproval of animal cloning research is particularly common in France (80%), Germany (79%), Italy (77%), the Czech Republic (75%) and the Netherlands (73%).

Men are more supportive than women of animal cloning research, although no more than about half of men across these publics say that animal cloning research is appropriate. Younger adults are more supportive of animal cloning research in all but three places surveyed, and those with higher levels of education are generally more supportive of such research.

Christians are often more disapproving than religiously unaffiliated adults of animal cloning research, although about half or more of both groups say this research is misusing technology across the 20 publics.

In the U.S., for example, about half of unaffiliated Americans (49%) say animal cloning research is appropriate, compared with about a quarter of Christians (27%). There are similar differences in Canada, the UK, Sweden, Australia, the Netherlands, Italy and Spain.

Elsewhere, differences among religious groups are less pronounced, including in France, Germany, India, Japan, South Korea and Russia.

In Taiwan, Taoists (46%) and unaffiliated (52%) adults are more accepting of animal cloning research than either Buddhists (34%) or Christians (32%).

Malaysian Buddhists are more likely than Malaysian Muslims to say animal cloning research is appropriate (48% vs. 34%, respectively).

There is broad public support for research on technologies that would help women get pregnant

In contrast to views about gene editing and animal cloning research, majorities in all places surveyed say that research into new technologies to help women get pregnant is appropriate (median of 73%). A median of just 21% say such research is a misuse of technology.

One of the better-known technologies aimed at helping women get pregnant is in vitro fertilization, or IVF. Once controversial, IVF is now in common use. There are a host of other biotechnologies being developed to aid reproduction. For example, some think 3D printing could one day be used to repair ovaries and restore fertility.

There is broad public support for research on pregnancy technologies. The Japanese are among the least supportive of new technologies to help women conceive. A slim majority sees such research as appropriate (56%), while 28% say it is misusing technology.

Women and men feel similarly positive about research on technologies that help women conceive in most publics surveyed.

Younger adults and the more highly educated tend to be more supportive of research in this area.

Larger shares of younger than older adults say research on new pregnancy technologies is appropriate in 16 of the 20 publics surveyed.

Age gaps are particularly large in Brazil and Japan. In Brazil, 78% of people who are at or younger than the country’s median age supports this kind of research, compared with 49% of older adults. The gap between older and younger adults is similar in size in Japan (69% vs. 43%, respectively).

Those with more education are especially likely to approve of research on new pregnancy technologies in most places surveyed. Differences by education are largest in Brazil (25 percentage points), followed by Italy (17 percentage points).

Religion plays a modest role in public views about this issue. As with other areas of biotechnology research, unaffiliated adults tend to be more accepting of research on new pregnancy technology than are Christians in most Western nations surveyed.

In one-on-one interviews the Center conducted in Singapore and Malaysia, Buddhist and Hindu interviewees generally spoke favorably about research on new pregnancy technologies, such as IVF. Muslims interviewees also discussed this kind of research in positive terms, though a number of interviewees noted their approval depended on how such procedures are used. In particular, Muslim interviewees said these procedures should only be available to married couples and should only use the husband and wife’s genetic material.

The Center survey finds roughly seven-in-ten Malaysian Muslims, Buddhists and Christians see such research as appropriate, as do roughly three-quarters of Buddhists and Christians and 57% of Muslims in Singapore. There is also broad support for such research in Taiwan among both Buddhists and Taoists. Religiously unaffiliated adults have similar views to other religious groups in Singapore and Taiwan.

Majorities in most publics accept evolution, but there are differences across religious groups

Evolution, a foundational theory for much of modern biology, has long been a source of conflict between religion and science.

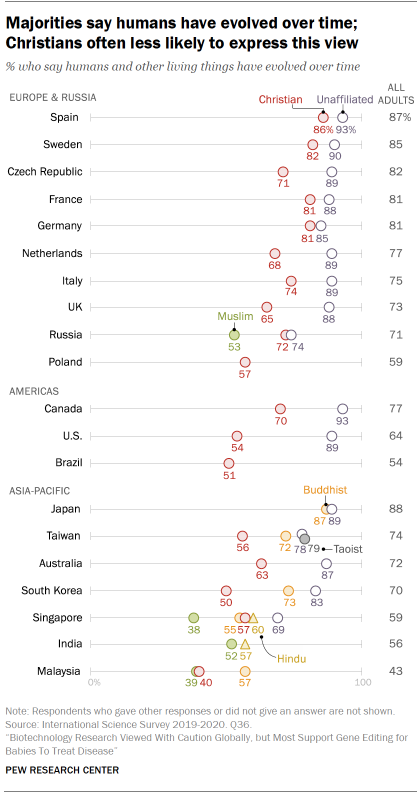

The Center survey found broad acceptance of evolution across publics. A median of 74% say humans and other living things have evolved over time, while a median of just 21% say humans and other living things have existed in their present form since the beginning of time.

Eight-in-ten or more in Japan, Spain, Sweden, the Czech Republic, France and Germany say humans and other living things have evolved over time, as do majorities elsewhere. Malaysia is the only public in which the balance of opinion is the opposite (43% vs. 55% saying humans and other living things have existed in their present form since the beginning of time).

Beliefs about evolution are strongly linked with religious affiliation. Larger shares of Christians say that humans and other living things have existed over time in their present form. In contrast, unaffiliated adults are generally more accepting of evolution. Differences between Christians and the unaffiliated are particularly wide in the U.S. and in South Korea (a 35 and 33 percentage point gap, respectively).

Similarly, Christians are at least 20 points less likely than the unaffiliated to accept evolution in Australia, the UK, Canada, the Netherlands and in Taiwan.

Christians for whom religion is more salient are less accepting of the idea that humans and other living things have evolved over time. In Canada, for example, about half of Christians who say religion is very important to them (49%) accept evolution, compared with 89% of Christians for whom religion is not too or not at all important. (See Appendix for more details.)

Followers of Islam also tend to be less accepting of evolution. In Malaysia and Singapore, roughly four-in-ten Muslims say that humans and other living things have evolved. In India and Russia, roughly half say this.

A Center survey of Muslims worldwide conducted in 2011 and 2012 found acceptance of evolution varied across world regions and countries. Muslims in South and Southeast Asian publics in that study also expressed lower levels of belief that humans and other living things have evolved over time.

During in-depth interviews, Muslim interviewees in Singapore and Malaysia often brought up concerns that the theory of evolution is incompatible with the Islamic tenet that humans were created by Allah, though Muslim interviewees sometimes differed in their own views about this.

Buddhists, followers of a religion with no creator figure, are generally more accepting of evolution. Majorities of Buddhists in Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Malaysia and Singapore say that humans and other living things have evolved over time.

In Taiwan, at least seven-in-ten Buddhists (72%), Taoists (79%) and religiously unaffiliated (78%) accept evolution. By comparison, 56% of Christians in Taiwan say the same.

Majorities of Hindus in India (57%) and Singapore (60%) say that humans and other living things have evolved over time.

These findings are broadly aligned with Center findings from qualitative interviews conducted with Buddhists and Hindus in Singapore and Malaysia.

More educated adults are often more likely to accept theory of evolution

People’s beliefs about evolution also vary with their level of education. Across 18 of 20 publics, those with more education are more accepting of evolution, saying that humans and other living things have evolved over time. Differences between those with more and less education range from 27 percentage points in Singapore to 8 percentage points in Japan, where large majorities at both levels of education say humans and other living things have evolved. Malaysia and the Czech Republic are the only places where those with more and less education are about equally likely to accept evolution.

Differences in beliefs about evolution by education hold even when looking only at those who are affiliated with a religion. In a handful of places, those who have also completed more science training are especially likely to say that humans and other living things have evolved over time. (See Appendix for more.)

Those who reject evolution are of two minds about whether scientific and religious explanations on the origins of life can be compatible

The Center survey also captured respondents’ sense of the degree to which scientific and religious explanations related to evolution are at odds.

Those who believe humans and other living things have existed in their present form throughout time are closely divided over whether or not scientific and religious explanations for the origins of life can be compatible. A median of 48% across the 17 publics with a large enough sample for analysis say they can, while a median of 45% say the two cannot be compatible.

For example, among Americans who reject evolution, 48% think scientific and religious explanations for the origins of life can be compatible, while an equal share (49%) says otherwise. There are wide differences of opinion on this question across all publics surveyed.

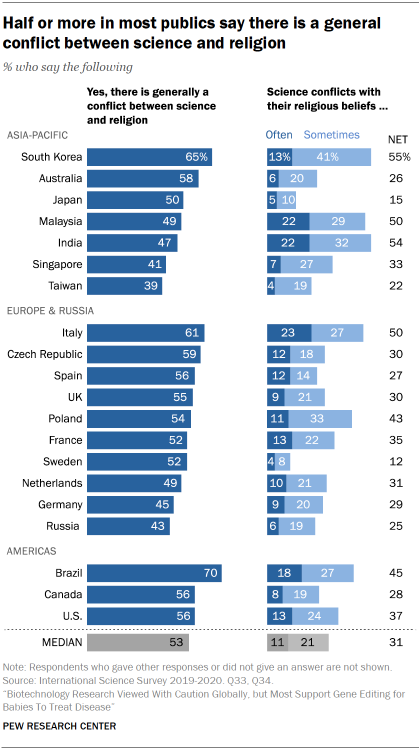

While some see a general conflict between science and religion, few say their own religious beliefs are often in tension with science

There is a long-standing debate about whether science and religion are compatible with one another, inherently at odds, or perhaps best seen in some other way altogether.

Asked to report how often their personal religious beliefs conflict with science, a median of just one-in-ten say there is often conflict. A median of 31% across the 20 publics surveyed say such conflict occurs at least sometimes. Majorities across most of these publics say there is rarely or never conflict between the two.

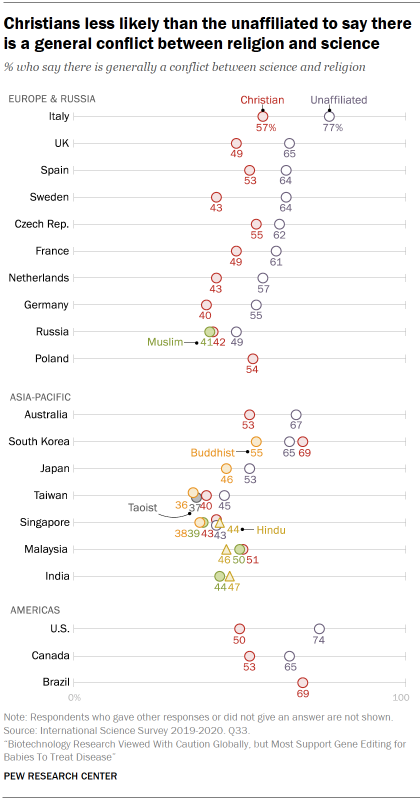

But when people think about the broad idea of whether science and religion are at odds, larger shares see the two as being in conflict (20-public median of 53%). That point of view is particularly common among people who do not identify with a religious group.

Views about these issues tend to vary by religion as well as place, however.

Religiously unaffiliated adults are more inclined than others to see a general conflict between science and religion. Half or more unaffiliated say the two conflict in 13 of these publics.

Differences between the affiliated and unaffiliated are more pronounced in places with a larger Christian population, including the U.S., Canada, Australia, Sweden and a number of other Western European nations.

In more religiously diverse places such as Singapore and Taiwan, about half or more of all religious groups with large enough samples for separate analysis say there is no conflict between science and religion.

In India, Hindus and Muslims are about equally likely to say religion and science generally conflict (47% and 44%). And in Malaysia, Muslims and Buddhists are about equally likely to say religion and science are generally at odds (50% and 46%). (There are not enough unaffiliated adults in the survey samples for separate analysis in either country.)

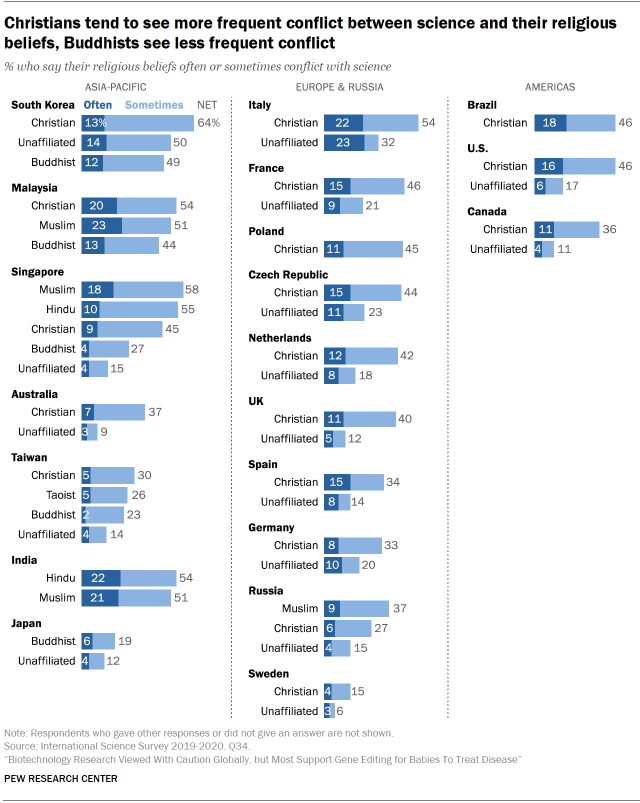

Followers of Christianity and Islam see more frequent conflict between science and their religious beliefs

To the extent that people experience conflict, Christians tend to think a tension between science and their religious beliefs occurs more frequently than do those who are unaffiliated. The share of Christians who say conflict between the two occurs at least sometimes is highest in South Korea (64%), Malaysia (54%) and Italy (54%). Elsewhere, the share of Christians who say there is often or sometimes conflict between science and their beliefs falls short of half.

Half or more Muslims in Singapore (58%), India (51%) and Malaysia (51%) say their religious beliefs are at odds with science at least sometimes. In Russia, the only other place surveyed with enough Muslim respondents for separate analysis, 37% say there is often or sometimes tension between science and their religious beliefs.

In a Center study using in-depth interviews in Singapore and Malaysia, Muslim interviewees offered a wide range of views about the relationship between science and their religion. One Muslim woman (age 20) in Singapore described it this way: “I feel like, sometimes, or most of the time, they are against each other. … Science is about experimenting, researching, finding new things, or exploring different possibilities. But then, religion is very fixed, to me.” But a Muslim man in Malaysia (age 24) offered a different perspective: “I think there is not any conflict between them. … In my opinion, I still believe that it happens because of God, just that the science will help to explain the details about why it is happening.”

By comparison, Buddhists tend to say conflict is less common. For example, 27% of Buddhists in Singapore, 23% in Taiwan and 19% in Japan say their religious beliefs at least sometimes conflict with science. Although 44% of Buddhists in Malaysia say this occurs at least sometimes, as do 49% of Buddhists in South Korea. In the same Center study using in-depth interviews, many Buddhists interviewees described science and religion as separate spheres. For example, one Buddhist woman in Singapore (age 26) said, “Science to me is statistics, numbers, texts – something you can see, you can touch, you can hear. Religion is more of something you cannot see, you cannot touch, you cannot hear. I feel like they are different faculties.”

Religious salience also plays a role in how often people experience conflict between their religious beliefs and science. Differences by religious salience are especially pronounced in places with larger shares of Christians in the West. In the Netherlands, the UK, Canada and the U.S., about half or more of affiliated adults who say religion is very important also say that conflict between science and their beliefs occurs at least sometimes. No more than a quarter of those who are affiliated and say religion is not too or not at all important in these countries say this. (See the Appendix)

The vast majority of Muslims in Malaysia, India and Singapore say that religion is very important in their lives.

In India, three-quarters of Hindus say that religion is very important in their lives. About eight-in-ten Hindus in India (79%) have a shrine or temple in their home. Those that do are more likely than Hindus who don’t to say their religious beliefs and science are often in competition (24% vs. 16%).

Buddhists stand out for their smaller shares of followers who describe religion as very important in their lives. Religious salience is not closely related to how often Buddhists say their religious beliefs conflict with science in the places surveyed. Nor are their sizable differences in views on this question between Buddhists who have a shrine at home and those who do not.