Five years ago this month, news organizations broke stories about federal government surveillance of phone calls and electronic communications of U.S. and foreign citizens, based on classified documents leaked by then-National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden. The initial stories and subsequent coverage sparked a global debate about surveillance practices, data privacy and leaks.

Here are some key findings about Americans’ views of government information-gathering and surveillance, drawn from Pew Research Center surveys since the NSA revelations:

1Americans were divided about the impact of the leaks immediately following Snowden’s disclosures, but a majority said the government should prosecute the leaker. About half of Americans (49%) said the release of the classified information served the public interest, while 44% said it harmed the public interest, according to a Pew Research Center survey conducted days after the revelations. While adults younger than 30 were more likely than older Americans to say the leaks served the public interest (60%), there was no partisan divide in these views.

At the same time, 54% of the public said the government should pursue a criminal case against the person responsible for the leaks, a view more commonly held among Republicans and Democrats (59% each) than independents (48%). Snowden was charged with espionage in June 2013. He then fled the U.S. and continues to live in Russia under temporary asylum.

2Americans became somewhat more disapproving of the government surveillance program itself in the ensuing months, even after then-President Barack Obama outlined changes to NSA data collection. The share of Americans who disapproved of the government’s collection of telephone and internet data as part of anti-terrorism efforts increased from 47% in the days after the initial disclosure to 53% the following January.

Other research by the Center also showed that a majority of adults (56%) did not think courts were providing adequate limits on the phone and internet data being collected. Moreover, 70% believed that the government was using surveillance data for purposes beyond anti-terror efforts. Some 27% said they thought the government listened to the actual contents of their calls or read their emails. (Similar figures emerged in a 2017 survey.)

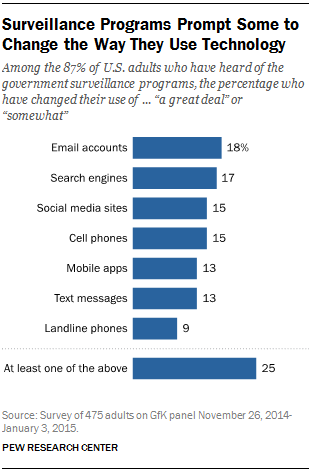

3 Disclosures about government surveillance prompted some Americans to change the way they use technology. In a survey by the Center in late 2014 and early 2015, 87% of Americans said they had heard at least something about government surveillance programs. Among those who had heard something, 25% said they had changed the patterns of their technology use “a great deal” or “somewhat” since the Snowden revelations.

Disclosures about government surveillance prompted some Americans to change the way they use technology. In a survey by the Center in late 2014 and early 2015, 87% of Americans said they had heard at least something about government surveillance programs. Among those who had heard something, 25% said they had changed the patterns of their technology use “a great deal” or “somewhat” since the Snowden revelations.

On a different question, 34% of those who were aware of the government surveillance programs said they had taken at least one step to hide or shield their information from the government, such as by changing their privacy settings on social media.

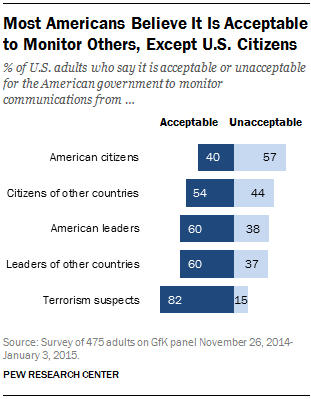

4 Americans broadly found it acceptable for the government to monitor certain people, but not U.S. citizens, according to the 2014-15 survey. About eight-in-ten adults (82%) said it was acceptable for the government to monitor communications of suspected terrorists, and equal majorities said it was acceptable to monitor communications of American leaders and foreign leaders (60% each). Yet 57% of Americans said it was unacceptable for the government to monitor the communications of U.S. citizens.

Americans broadly found it acceptable for the government to monitor certain people, but not U.S. citizens, according to the 2014-15 survey. About eight-in-ten adults (82%) said it was acceptable for the government to monitor communications of suspected terrorists, and equal majorities said it was acceptable to monitor communications of American leaders and foreign leaders (60% each). Yet 57% of Americans said it was unacceptable for the government to monitor the communications of U.S. citizens.

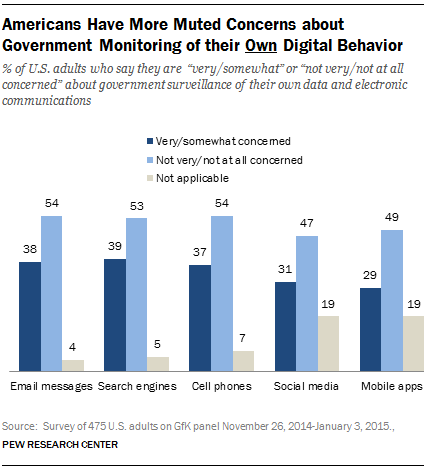

5 About half of Americans (52%) expressed worry about surveillance programs in 2014 and 2015, but they had more muted concerns about surveillance of their own data. Roughly four-in-ten said they were somewhat or very concerned about government monitoring of their activity on search engines, email messages and cellphones. Roughly three-in-ten expressed the same amount of concern over monitoring of their activity on social media and mobile apps.

About half of Americans (52%) expressed worry about surveillance programs in 2014 and 2015, but they had more muted concerns about surveillance of their own data. Roughly four-in-ten said they were somewhat or very concerned about government monitoring of their activity on search engines, email messages and cellphones. Roughly three-in-ten expressed the same amount of concern over monitoring of their activity on social media and mobile apps.

6The vast majority of Americans (93%) said that being in control of who can get information about them is important, according to a 2015 report. At the same time, a similarly large majority (90%) said that controlling what information is collected about them is important.

Few Americans, however, said that they had a lot of control over the information that is collected about them in daily life. Just 9% of Americans said they had a lot of control over the information that is collected about them. In an earlier survey, 91% agreed with the statement that consumers have lost control of how personal information is collected and used by companies.

Few Americans, however, said that they had a lot of control over the information that is collected about them in daily life. Just 9% of Americans said they had a lot of control over the information that is collected about them. In an earlier survey, 91% agreed with the statement that consumers have lost control of how personal information is collected and used by companies.

7Some 49% said in 2016 that they were not confident in the federal government’s ability to protect their data. About three-in-ten Americans (28%) were not confident at all in the government’s ability to protect their personal records, while 21% were not too confident. Just 12% of Americans were very confident in the government’s ability to protect their data (49% were at least somewhat confident).

Americans had more confidence in other institutions, such as cellphone manufacturers and credit card companies, to protect their data. Around seven-in-ten cellphone owners were very (27%) or somewhat (43%) confident that cellphone manufacturers could keep their personal information safe. Similarly, around two-thirds of online adults were very (20%) or somewhat (46%) confident that email providers would keep their information safe and secure.

8Roughly half of Americans (49%) said their personal data were less secure compared with five years prior, according to the 2016 survey. The Snowden revelations were followed in the ensuing months and years with accounts of major data breaches affecting the government and commercial firms. These vulnerabilities appear to have taken a toll. Americans ages 50 and older were particularly likely to express concerns over the safety of their data: 58% of these older Americans said their data were less secure than five years prior. Younger adults were less concerned about their data being less secure; still, 41% of 18- to 49-year-olds felt their personal information was less secure than five years earlier.