It has been nearly two years since the first disclosures of government surveillance programs by former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden and Americans are still coming to terms with how they feel about the programs and how to live in light of them. The documents leaked by Snowden revealed an array of activities in dozens of intelligence programs that collected data from large American technology companies, as well as the bulk collection of phone “metadata” from telecommunications companies that officials say are important to protecting national security. The metadata includes information about who phone users call, when they call, and for how long. The documents further detail the collection of Web traffic around the globe, and efforts to break the security of mobile phones and Web infrastructure.

A new survey by the Pew Research Center asked American adults what they think of the programs, the way they are run and monitored, and whether they have altered their communication habits and online activities since learning about the details of the surveillance. The notable findings in this survey fall into two broad categories: 1) the ways people have personally responded in light of their awareness of the government surveillance programs and 2) their views about the way the programs are run and the people who should be targeted by government surveillance.

Some people have changed their behaviors in response to surveillance

Overall, nearly nine-in-ten respondents say they have heard at least a bit about the government surveillance programs to monitor phone use and internet use. Some 31% say they have heard a lot about the government surveillance programs and another 56% say they had heard a little. Just 6% suggested that they have heard “nothing at all” about the programs. The 87% of those who had heard at least something about the programs were asked follow-up questions about their own behaviors and privacy strategies:

34% of those who are aware of the surveillance programs (30% of all adults) have taken at least one step to hide or shield their information from the government. For instance, 17% changed their privacy settings on social media; 15% use social media less often; 15% have avoided certain apps and 13% have uninstalled apps; 14% say they speak more in person instead of communicating online or on the phone; and 13% have avoided using certain terms in online communications.

Those most likely to have taken these steps include adults who have heard “a lot” about the surveillance programs and those who say they have become less confident in recent months that the programs are in the public interest. Younger adults under the age of 50 are more likely than those ages 50 and older to have changed at least one of these behaviors (40% vs. 27%). There are no notable differences by political partisanship when it comes to these behavior changes.

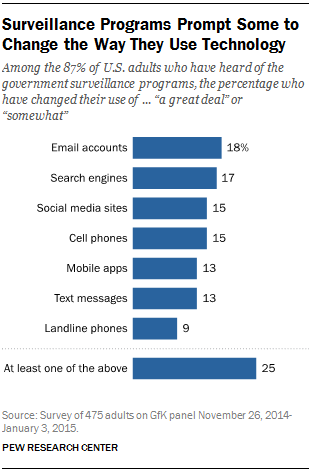

25% of those who are aware of the surveillance programs (22% of all adults) say they have changed the patterns of their own use of various technological platforms “a great deal” or “somewhat” since the Snowden revelations. For instance, 18% say they have changed the way they use email “a great deal” or “somewhat”; 17% have changed the way they use search engines; 15% say they have changed the way they use social media sites such as Twitter and Facebook; and 15% have changed the way they use their cell phones.

25% of those who are aware of the surveillance programs (22% of all adults) say they have changed the patterns of their own use of various technological platforms “a great deal” or “somewhat” since the Snowden revelations. For instance, 18% say they have changed the way they use email “a great deal” or “somewhat”; 17% have changed the way they use search engines; 15% say they have changed the way they use social media sites such as Twitter and Facebook; and 15% have changed the way they use their cell phones.

Those who are more likely to have changed at least one of their behaviors include the people who have heard a lot about government surveillance (38% say they have changed a great deal/somewhat in at least one of these activities), those who are at least somewhat concerned about the programs (41% have changed at least one activity), and those who are concerned about government monitoring of their use of social media, search engines, cell phones, apps, and email.

There are no partisan differences when it comes to those who have changed their use of various technologies.

Additionally, a notable share of Americans have taken specific technical steps to assert some control over their privacy and security, though most of them have done just simple things. For instance, 25% of those who are aware of the surveillance programs are using more complex passwords.

Many have not considered or are not aware of some of the more commonly available tools that could make their communications and activities more private

One potential reason some have not changed their behaviors is that 54% believe it would be “somewhat” or “very” difficult to find tools and strategies that would help them be more private online and in using their cell phones. Still, notable numbers of citizens say they have not adopted or even considered some of the more commonly available tools that can be used to make online communications and activities more private:

- 53% have not adopted or considered using a search engine that doesn’t keep track of a user’s search history and another 13% do not know about these tools.

- 46% have not adopted or considered using email encryption programs such as Pretty Good Privacy (PGP) and another 31% do not know about such programs.

- 43% have not adopted or considered adding privacy-enhancing browser plug-ins like DoNotTrackMe (now known as Blur) or Privacy Badger and another 31% do not know such plug-ins.

- 41% have not adopted or considered using proxy servers that can help them avoid surveillance and another 33% do not know about this.

- 40% have not adopted or considered using anonymity software such as Tor and another 39% do not know about what that is.

These figures may in fact understate the lack of awareness among Americans because noteworthy numbers of respondents answered “not applicable to me” on these questions even though virtually all of them are internet and cell phone users.

The public has divided sentiments about the surveillance programs

This survey asked the 87% of respondents who had heard about the surveillance programs: “As you have watched the developments in news stories about government monitoring programs over recent months, would you say that you have become more confident or less confident that the programs are serving the public interest?” Some 61% of them say they have become less confident the surveillance efforts are serving the public interest after they have watched news and other developments in recent months and 37% say they have become more confident the programs serve the public interest. Republicans and those leaning Republican are more likely than Democrats and those leaning Democratic to say they are losing confidence (70% vs. 55%).

Moreover, there is a striking divide among citizens over whether the courts are doing a good job balancing the needs of law enforcement and intelligence agencies with citizens’ right to privacy: 48% say courts and judges are balancing those interests, while 49% say they are not.

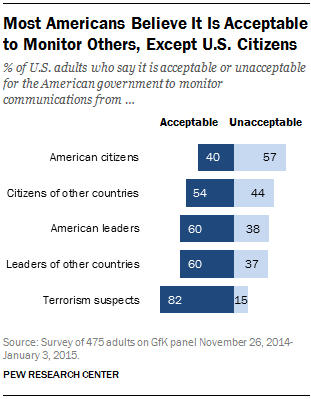

At the same time, the public generally believes it is acceptable for the government to monitor many others, including foreign citizens, foreign leaders, and American leaders:

At the same time, the public generally believes it is acceptable for the government to monitor many others, including foreign citizens, foreign leaders, and American leaders:

- 82% say it is acceptable to monitor communications of suspected terrorists

- 60% believe it is acceptable to monitor the communications of American leaders.

- 60% think it is okay to monitor the communications of foreign leaders

- 54% say it is acceptable to monitor communications from foreign citizens

Yet, 57% say it is unacceptable for the government to monitor the communications of U.S. citizens. At the same time, majorities support monitoring of those particular individuals who use words like “explosives” and “automatic weapons” in their search engine queries (65% say that) and those who visit anti-American websites (67% say that).

Americans are split when it comes to being concerned about surveillance programs

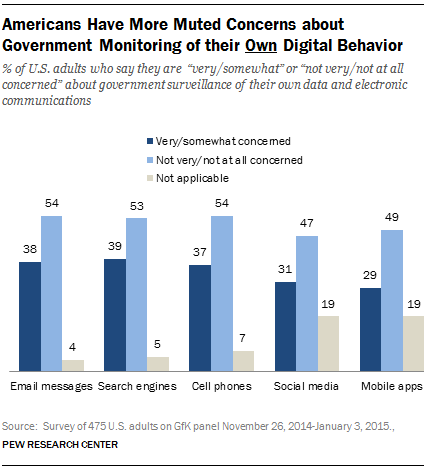

Overall, 52% describe themselves as “very concerned” or “somewhat concerned” about government surveillance of Americans’ data and electronic communications, compared with 46% who describe themselves as “not very concerned” or “not at all concerned” about the surveillance. When asked about more specific areas of concern over their own communications and online activities, respondents expressed somewhat lower levels of concern about electronic surveillance in various parts of their digital lives:

Overall, 52% describe themselves as “very concerned” or “somewhat concerned” about government surveillance of Americans’ data and electronic communications, compared with 46% who describe themselves as “not very concerned” or “not at all concerned” about the surveillance. When asked about more specific areas of concern over their own communications and online activities, respondents expressed somewhat lower levels of concern about electronic surveillance in various parts of their digital lives:

- 39% describe themselves as “very concerned” or “somewhat concerned” about government monitoring of their activity on search engines.

- 38% say they are “very concerned” or “somewhat concerned” about government monitoring of their activity on their email messages.

- 37% express concern about government monitoring of their activity on their cell phone.

- 31% are concerned about government monitoring of their activity on social media sites, such as Facebook or Twitter.

- 29% say they are concerned about government monitoring of their activity on their mobile apps.

More about this survey

The analysis in this report is based on a Pew Research Center survey conducted between November 26, 2014 and January 3, 2015 among a sample of 475 adults, 18 years of age or older. The survey was conducted by the GfK Group using KnowledgePanel, its nationally representative online research panel. GfK selected a representative sample of 1,537 English-speaking panelists to invite to join the subpanel and take the first survey in the fall of 2014. Of the 935 panelists who responded to the invitation (60.8%), 607 agreed to join the subpanel and subsequently completed the first survey (64.9%) whose results were reported in November 2014. This group has agreed to take four online surveys about “current issues, some of which relate to technology” over the course of a year and possibly participate in one or more 45-60-minute online focus group chat sessions. For the third survey whose results are reported here, 475 of the original 607 panelists participated. A random subset of the subpanel receive occasional invitations to participate in online focus groups. For this report, a total of 59 panelists participated in one of six online focus groups conducted during December 2014 and January 2015. Sampling error for the total sample of 475 respondents is plus or minus 5.6 percentage points at the 95% level of confidence.

For more information on the GfK Privacy Panel, please see the Methods section at the end of this report.