Contrary to assertions that people “don’t care” about privacy in the digital age, this survey suggests that Americans hold a range of strong views about the importance of control over their personal information and freedom from surveillance in daily life. As earlier studies in this series have illustrated, Americans’ perceptions of privacy are varied in important ways and often overlap with concerns about personal information security and government surveillance. In practice, information scholars have noted that privacy is not something one can simply “have,” but rather is something people seek to “achieve” through an ongoing process of negotiation of all the ways that information flows across different contexts in daily life.

The data from the new Pew Research surveys suggest that Americans consider a wide array of privacy-related values to be deeply important in their lives, particularly when it comes to having a sense of control over who collects information and when and where activities can be observed.

When they are asked to think about all of their daily interactions – both online and offline – and the extent to which certain privacy-related values are important to them, clear majorities believe every dimension below is at least “somewhat important” and many express the view that these aspects of personal information control are “very important.”5 The full range of their views is captured in the chart below and more detailed analysis is explored after that.

Nine-in-ten adults feel various dimensions of control over personal information collection are “very important” to them.

The issue of who is gathering information and what information is being gathered is considered to be an important dimension of privacy control by nearly all American adults. In all, 93% of adults say that being in control of who can get information about them is important; 74% feel this is “very important,” while 19% say it is “somewhat important.”

At the same time, 90% say that controlling what information is collected about them is important– 65% think it is “very important” and 25% say it is “somewhat important.” There are no significant age- or gender-based differences for either of these questions.

As earlier surveys have demonstrated, the sensitivity level of various types of information varies considerably, with social security numbers topping the list of the most sensitive pieces of information and basic purchasing habits being viewed as the least sensitive kind of data.

Americans value having the ability to share confidential matters with another trusted person.

While public c0nfidence in the security of various communications channels is low, Americans continue to value the ability to share confidential information with others in their lives. Nine-in-ten (93%) adults say that this is important to them, with 72% saying it is “very important” and 21% saying it is “somewhat important” to have this ability to share confidential information with trusted parties. Men, women and adults of all ages are equally likely to hold these views.

Permission and publicness are key features that influence views on surveillance.

Americans say they do not wish to be observed without their approval; 88% say that it is important that they not have someone watch or listen to them without permission (67% feel this is “very important” and 20% say it is “somewhat important” to them).

However, far fewer (63%) feel it is important to be able to “go around in public without always being identified.” Only 34% believe being able to go unnoticed in public is “very important” and 29% say it is “somewhat important.” In both cases, all adults, regardless of age or gender, express comparable views.

For many, homes really are “do not disturb” zones.

Americans do not appreciate being bothered at home. Fully 85% say that not being disturbed at home is important to them. Some 56% say it is very important they not be bothered at home and another 29% say it is “somewhat important” they be free from disturbances at home.

Americans treasure the ability to be alone at times and they do not appreciate intrusive inquiries about personal matters.

Some 85% of adults say it is important to be able to have times when they are completely alone, away from anyone else. Fully 55% say this is “very important” to them and another 30% say this is somewhat important. These with high school educations or less are not as likely as those with at least some college experience or college graduates to say that being alone matters to them. Women and men show no difference in their answer on this question, nor do those in different age groups.

On a separate question, 79% say that it “very” or “somewhat” important to them not to have people at work or social situations ask them about things that are “highly personal.” Some 44% say that avoiding prying acquaintances is “very important” to them and another 36% say this is “somewhat important.”

The ability to avoid “highly personal” questions is an especially important virtue to those over age 50. Some 52% say it is very important to them not to be asked about highly personal matters, compared with 37% of those ages 18-49 who feel that level of sensitivity. In addition, women (84%) are more likely than men (74%) to say that it is important to them not to have people ask them highly personal questions in work and social situations.

By a 2-to-1 margin, people think it is important not to be monitored at work.

Some 56% of Americans say it is important to them not to be monitored at work, compared with 27% who say it is not very or not at all important. Another 15% of adults say they do not know or this issue does not apply to them. Twenty-eight percent say it is “very important” not to be monitored at work and another 28% say it is “somewhat important.”6

Even as they value the ability to be free from observation, Americans feel it is hard to avoid surveillance in public.

While the patterns of one’s digital communications and behaviors have been the focus of much of the recent public discussion about surveillance, Americans also have a pervasive sense that their physical activities may be recorded when they are moving about their daily lives. In the first survey in this series, Americans were asked whether or not they agree that “it is hard to avoid surveillance cameras when I am out in public.”7 The vast majority – 81% – agree that surveillance cameras are hard to avoid; 36% say they “strongly agree” and 45% “agree.”

Majorities of every demographic group said they feel this way, with relatively minor variation in the responses. For instance, the oldest adults in the sample were somewhat more likely than those under the age of 50 to feel that surveillance cameras are hard to avoid when they are out in public; 90% of adults ages 65 and older agree that surveillance cameras are hard to avoid in public, compared with 76% of those ages 18-29 and 80% of those ages 30-49 who feel that way.

Similarly, in online focus groups conducted for this report, respondents were prompted to think about specific examples of the kinds of data and information that might be recorded or collected about them. When asked about the kinds of observation that might happen as they are walking down the street, many mentioned the presence of cameras of various kinds. And while most cast these observations in a negative light, some noted that they can be a boon to public safety:

When you are walking down the street, do you ever think that you are being observed in a way that would create a kind of record about where you’ve been that could be accessed later?

“CCTV Cameras are all over the place plus there [are] satellites. All kind[s of] stuff.”

“We are always on video. We leave [an] imprint as soon as we leave our house.”

“I’m frightened by high resolution satellite cameras.”

“Sites visited, purchases made. You are always being filmed on cameras … which can be a good thing if you are assaulted.”

“Big Bro is always watching.”

Few feel they have “a lot” of control over how much information is collected about them in daily life.

While Americans clearly value having control over their personal information, few feel they have the ability to exert that control. Beyond surveillance cameras, there are many other forms of daily data collection and use that they do not feel they can avoid. When asked how much control they feel they have over how much information is collected about them and how it is used in their everyday lives, only a small minority of Americans say they have “a lot” of control.

Our question on this subject went as follows: Respondents were asked to think about a typical day in their lives as they spend time at home, outside their home, and getting from place to place. They were asked to consider that they might use their cellphone, landline phones or credit cards. They might go online and buy things, use search engines, watch videos or check in on social media. When thinking about all of these activities that might take place on a typical day, just 9% say they feel they have “a lot” of control over how much information is collected about them and how it is used, while 38% say they have “some control.” Another 37% assert they have “not much control,” and 13% feel they personally have “no control at all” over the way their data is gathered and used.

While there are some minor variations across socioeconomic groups, men, women and adults of all ages report similar views.

In keeping with other research on technology use and perceptions of control, social media users are more likely than non-users to believe they have “a lot” of control over how much information is collected about them and how it is used; 11% feel this way vs. 4% of non-users. However, it is still the case that about half of all social media users feel they have “not much” or “no control at all” over personal data collection and use in daily life.8

Those who are more aware of government surveillance efforts feel they have less control over the way their information is collected and used on a typical day.

At the time of this survey, 81% of adults had at least some low level of awareness about the government collecting information about telephone calls, emails and other online communications. One-in-three (32%) said they had heard “a lot” about the programs and almost half (48%) said they had heard “a little.”9 Those who were among the most likely to hear “a lot” about the programs include adults ages 50 and older (40%) and those with a college degree (44%).

Those who are more aware of government surveillance efforts say they have less control over the way their information is collected and used on a typical day; 60% of those who have heard “a lot” about the government collecting information about communications said they feel they have “not much” or “no control at all” over the way their data is gathered and used compared with 47% of those who have heard only “a little” about the monitoring programs.

Focus group discussions suggest that many want more transparency in who collects information about them, but some don’t care or don’t worry.

In the online focus group discussions, a subset of the survey respondents was asked whether or not they feel as though they “know enough” about who collects data about them and why it is being collected. Among those who felt they don’t know enough, respondents noted multiple dimensions of unknowing, including where the data is stored, who has access to it and how it might be used:

Do you feel as though you know enough about who collects information about you and your activities or would you like to know more about who is doing the collecting and the reasons for it?

“No we don’t know who is always collecting it and the bigger question is where does it go and who also gets to see it.”

“No. Once it is collected, it has no expiration date … things collected 10 years ago about my daily patterns are relevant to what I do today? There is a great unknown to it all.”

“I would like to know more. I feel there is too much secrecy and perhaps the government wants there to be secrecy precisely so that they can monitor what people think they are not being monitored for!”

“I would like to know more about who is collecting information and for what reasons.”

“I would like to know everyone who is collecting data on me and what they are doing with it.”

“I know from personal experience that we don’t (and probably will never) know enough about who is collecting information and why. If people knew how much the Government knew about their day-to-day activities, we wouldn’t be so carefree with our lives.”

“Definitely would like to know who’s collecting information about me. What if you’re suspected of something unjustly.”

At the same time, another group of participants voiced the view that they “don’t care” or “don’t worry” about who might be collecting data about them and why:

“If I find out, fine. But I’m certainly not going to waste any time on it… too many other things to enjoy in life.”

“I do not care. I feel I don’t do anything wrong so I don’t have to worry.”

“I don’t worry too much about this. But I just wonder if the United States is still a free country that we all are looking for.”

“I lead a very placid life. I don’t know of any activity I could be doing that could track me for anything.”

When asked about the length of time that data should be retained by various institutions, most Americans feel that “a few months” or less is long enough to store most records of their activity.

Various organizations and companies often are required to retain information about customers or users for legal reasons or as part of their business operations. The length of time varies considerably across different organizations and according to the type of information being retained.10 Groups that set standards for records management and retention state that one of the core principles of the practice is to determine what is “an appropriate time, taking into account all operational, legal, regulatory and fiscal requirements, and those of all relevant binding authorities.”11

In this survey there is both wide variation across the length of time that respondents feel is reasonable to store their data, and considerable variance depending on the kind of organization that retains the records of the activity. In general, and even though it may be necessary to provide certain functionality, people are less comfortable with certain online service providers—such as search engine providers and social media sites—storing records and archives of their activity. For instance, 50% of adults think that online advertisers who place ads on the websites they visit should not save any information about their activity.12

At the other end of the spectrum, the vast majority of adults are comfortable with the idea that credit card companies might retain records or archives of their activity. However, the length of time that people feel is reasonable varies significantly. While few think that data about their credit card activity should only be stored for a few weeks (6%) or a few months (14%), many more consider a few years (28%) a reasonable length of time. Another 22% think credit card companies should store the information “as long as they need to” and just 13% think that credit card companies “shouldn’t save any information.”

The notable demographic variances across these questions include:

- Women are more likely than men to say that government agencies should retain their records “as long as they need to” (34% vs. 23%).

- Women are more likely than men to say that credit card companies should retain their records “as long as they need to” (27% vs. 17%).

- Large numbers (24%) of those under age 50 said that the question about landline telephone companies did not apply to them. By contrast, large numbers (30%) of those ages 50 and older said that the question about social media sites didn’t apply to them. A slightly smaller number (26%) of older adults said the same about online video sites.

Those who have greater awareness of the government monitoring programs are more likely to believe that certain records should not be saved for any length of time.

Those who have had the most exposure to information about the government surveillance programs also have some of the strongest views about data retention limits for certain kinds of organizations. These differences are particularly notable when considering social media sites; among those who have heard “a lot” about the government collecting communications data as part of anti-terrorism efforts, 55% say that the social media sites they use should not save any information regarding their activity, compared with 35% of those who have heard “a little” about the government monitoring programs.

Those who have had the most exposure to information about the government surveillance programs also have some of the strongest views about data retention limits for certain kinds of organizations. These differences are particularly notable when considering social media sites; among those who have heard “a lot” about the government collecting communications data as part of anti-terrorism efforts, 55% say that the social media sites they use should not save any information regarding their activity, compared with 35% of those who have heard “a little” about the government monitoring programs.

Focus group discussions highlight some of the public’s assumptions and concerns about data collection and surveillance in daily life.

In focus group conversations, panelists noted various ways that they assume information might be collected about them. Expansive government data collection efforts were cited by many respondents and several noted the ways in which hackers might access records that were gathered for other purposes.

Just off the top of your head, what kind of information about you and your activities do you think is being collected and who is collecting it?

“Anything digital can record, even a car today tells everything, your cellphone even when it is off is still sending info to the towers.”

“I have a cousin that was involved in the government. I believe that they try collecting as much information as they possibly can, especially after 9/11. They pretty much know when we sleep, eat, watch, t.v., make calls (and to whom), what videos we rent, and what we like to eat.”

“I think the NSA does most of the collecting. What they would get from me is location and site address I am accessing, I guess.”

“I believe that my search and order history on websites is being collected by companies that I order from.”

“Hackers … are trying to find out your credit card and other identity information.”

“Name, address, everybody in my family, my interests, anything I may want to purchase. I think it is collected by the government, and anybody who has great computer knowledge … can hack.”

“Web browsing (businesses, govt, hackers), credit card transactions (businesses, govt, hackers), cellphone texts and calls (govt)”

“I’m sure the government has buzz words that they take from texts or emails or blogs that they keep an eye on.”

“I think Facebook can be used as a key tool in getting info by the government & our cellphones.”

“I think even so-called “private” browsing could be explored by the government if they wanted access…not sure about Snap Chats–does anyone know?”

Americans have little confidence that their data will remain private and secure—particularly when it comes to data collected by online advertisers.

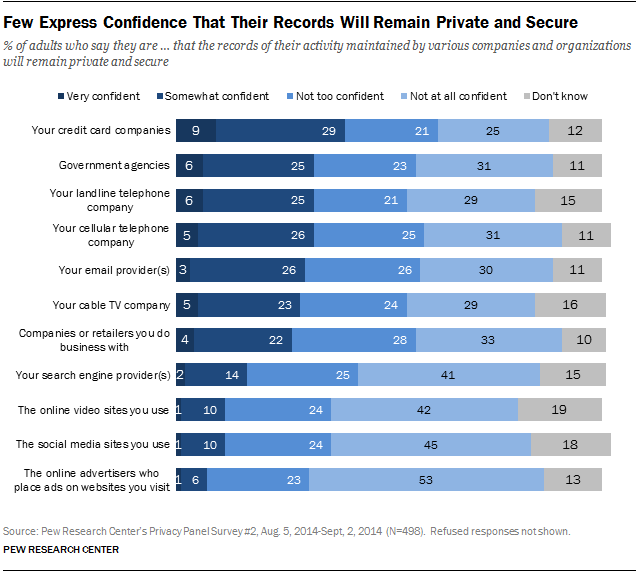

When they consider the various companies and organizations that maintain records of their activity, very few express confidence that the data records held by these institutions would remain private and secure. For all of the 11 entities we asked about – from government agencies to credit card companies to social media sites – only small minorities say they are “very confident” that the records maintained by these organizations will remain private and secure.13

However, there are notable variations in Americans’ confidence levels according to the type of organization being considered. For instance, just 6% of adults say they are very confident that government agencies can keep their records private and secure, while another 25% say they are somewhat confident.

Credit card companies appear to instill a marginally higher level of confidence when compared with other entities, but they still garner only 9% of respondents saying they are “very confident” and 29% saying they are “somewhat confident” that their data will stay private and secure.

Landline phone companies and cellphone companies are more trusted than digital communications providers, but neither instills great levels of confidence. For instance, just 6% of respondents say they are “very confident” that landline telephone companies will be able to protect their data and 25% say they are “somewhat confident” that the records of their activities will remain private and secure.

In keeping with the findings about the length of time various organizations might store records and archives of activity, online service providers are among the least trusted entities when it comes to keeping information private and secure. When asked about search engine providers, online video sites, social media sites and online advertisers, the majority felt “not too confident” or “not at all confident” that these entities could protect their data:

- 76% of adults say they are “not too confident” or “not at all confident” that records of their activity maintained by the online advertisers who place ads on the websites they visit will remain private and secure.

- 69% of adults say they are not confident that records of their activity maintained by the social media sites they use will remain private and secure.

- 66% of adults say they are not confident that records of their activity maintained by search engine providers will remain private and secure.

- 66% say they are not confident that records of their activity collected by the online video sites they use will remain private and secure.

Those who have heard “a lot” about the government monitoring programs are less confident in the privacy and security of their data.

Those who have heard “a lot” about the government monitoring programs are less confident in the privacy and security of their data across an array of scenarios. This is true when we ask questions about records maintained by a wide variety of institutions including government agencies, communications companies, landline telephone companies and various online service providers.

The share of Americans who disapprove of the government collection of telephone and internet data as part of anti-terrorism efforts continues to outweigh the number who approve.

Four-in-ten (40%) adults say they disapprove of the government’s collection of telephone and internet data as part of anti-terrorism efforts, while one-in-three (32%) say they approve. At the same time, more than one-in-four (26%) say they don’t know if they approve or disapprove.14 Adults ages 50 and older are considerably more likely to approve of the programs when compared with those under age 50 (42% vs. 24%). Younger adults under age 50 express more uncertainty when compared with older adults; 32% say they “don’t know” if they approve or disapprove of the programs, compared with 19% of those ages 50 and older.

Those who have heard “a lot” about the government monitoring programs are far more likely to disapprove of them: 60% disapprove of the programs compared with just 36% of those who have heard only “a little.”

However, as other surveys have indicated, Americans’ views vary substantially when they consider the idea of monitoring of U.S. citizens vs. foreign citizens. While only a minority of Americans feels it is acceptable for the government to monitor ordinary American citizens, many think it is acceptable to monitor others in a variety of other situations. Americans generally support monitoring foreign citizens and support the use of surveillance to investigate specific scenarios such as those involving criminal activity or suspected involvement with terrorism.15

65% of American adults believe there are not adequate limits on the telephone and internet data that the government collects.

The survey also reveals a broadly-held view that there should be greater restrictions on the kinds of information that the government is allowed to collect. When asked to think about the data the government collects as part of anti-terrorism efforts, 65% of Americans say there are not adequate limits on “what telephone and internet data the government can collect.” Just 31% say they believe that there are adequate limits on the kinds of data gathered for these programs.16

The majority view that there are not sufficient limits on what data the government gathers is consistent across all demographic groups with one modest variation. Those in the highest-income households are somewhat more likely than those in the lowest-income groups to say that the limits on government data collection are sufficient; 36% of adults living in households earning $75,000 or more per year think the limits on these programs are adequate, compared with 21% of those in households earning $30,000 or less per year.

Notably, those who are more aware of the government surveillance efforts are more likely to feel there are not adequate safeguards in place; 74% of those who have heard “a lot” about the programs say that there are not adequate limits, compared with 62% who have heard only “a little” about the monitoring programs.