What makes life meaningful? Answering such a big question might be challenging for many people. Even among researchers, there is little consensus about the best way to measure what brings human beings satisfaction and fulfillment. Traditional survey questions – with a prespecified set of response options – may not capture important sources of meaning.

To tackle this topic, Pew Research Center conducted two separate surveys in late 2017. The first included an open-ended question asking Americans to describe in their own words what makes their lives feel meaningful, fulfilling or satisfying. This approach gives respondents an opportunity to describe the myriad things they find meaningful, from careers, faith and family, to hobbies, pets, travel, music and being outdoors.

The second survey included a set of closed-ended (also known as forced-choice) questions asking Americans to rate how much meaning and fulfillment they draw from each of 15 possible sources identified by the research team. It also included a question asking which of these sources gives respondents the most meaning and fulfillment. This approach offers a limited series of options but provides a measure of the relative importance Americans place on various sources of meaning in their lives.

The second survey included a set of closed-ended (also known as forced-choice) questions asking Americans to rate how much meaning and fulfillment they draw from each of 15 possible sources identified by the research team. It also included a question asking which of these sources gives respondents the most meaning and fulfillment. This approach offers a limited series of options but provides a measure of the relative importance Americans place on various sources of meaning in their lives.

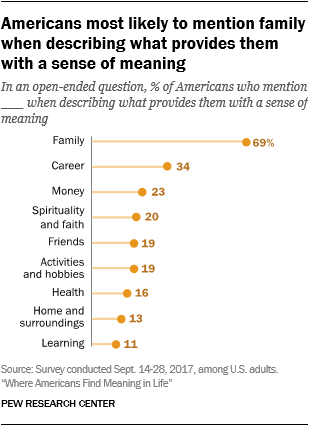

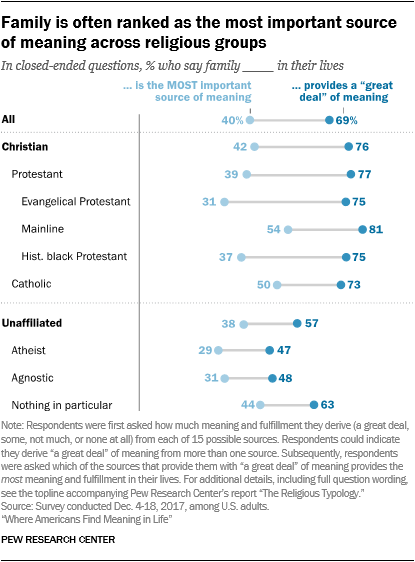

Across both surveys, the most popular answer is clear and consistent: Americans are most likely to mention family when asked what makes life meaningful in the open-ended question, and they are most likely to report that they find “a great deal” of meaning in spending time with family in the closed-ended question.

But after family, Americans mention a plethora of sources (in the open-ended question) from which they derive meaning and satisfaction: One-third bring up their career or job, nearly a quarter mention finances or money, and one-in-five cite their religious faith, friendships, or various hobbies and activities. Additional topics that are commonly mentioned include being in good health, living in a nice place, creative activities and learning or education. Many other topics also arose in the open-ended question, such as doing good and belonging to a group or community, but these were not as common.

But after family, Americans mention a plethora of sources (in the open-ended question) from which they derive meaning and satisfaction: One-third bring up their career or job, nearly a quarter mention finances or money, and one-in-five cite their religious faith, friendships, or various hobbies and activities. Additional topics that are commonly mentioned include being in good health, living in a nice place, creative activities and learning or education. Many other topics also arose in the open-ended question, such as doing good and belonging to a group or community, but these were not as common.

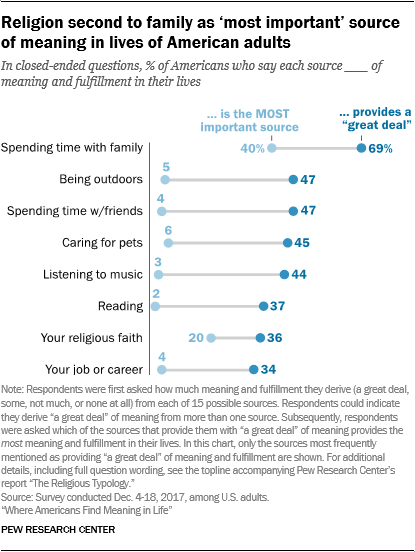

In the closed-ended question, the most commonly cited sources that provide Americans with “a great deal” of meaning and fulfillment (after family) include being outdoors, spending time with friends, caring for pets and listening to music. By this measure, religious faith ranks lower, on par with reading and careers. But among those who do find a great deal of meaning in their religious faith, more than half say it is the single most important source of meaning in their lives. Overall, 20% of Americans say religion is the most meaningful aspect of their lives, second only to the share who say this about family (40%).

People in a wide variety of social and demographic subgroups mention family as a key source of meaning and fulfillment. But there are some patterns in the sources of meaning that Americans cite, depending on their religion, socioeconomic status, race, politics and other factors.

People in a wide variety of social and demographic subgroups mention family as a key source of meaning and fulfillment. But there are some patterns in the sources of meaning that Americans cite, depending on their religion, socioeconomic status, race, politics and other factors.

Among the key findings from the surveys:

- Family is among the most popular topics across demographic groups. In response to the open-ended question, seven-in-ten Americans mention their family as a source of meaning and fulfillment, and a similar share say in the closed-ended question that family provides “a great deal” of meaning in their lives. While substantial shares in all major subgroups of Americans mention family, people who are married are more likely than are those who are not married to cite family as a key source of meaning.

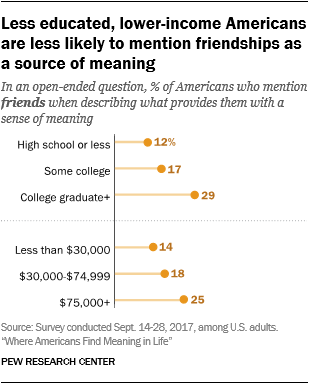

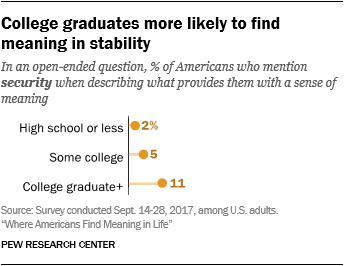

- Americans with high levels of household income and educational attainment are more likely to mention friendship, good health, stability and travel. A quarter of Americans who earn at least $75,000 a year mention their friends when asked to describe, in their own words, what makes life meaningful, compared with 14% of Americans who earn less than $30,000 each year. Similarly, 23% of higher-income U.S. adults mention being in good health, compared with 10% of lower-income Americans. And among those with a college degree, 11% mention travel and a sense of security as things that make their lives fulfilling, compared with 3% and 2%, respectively, who name these sources of meaning among those with a high school degree or less.

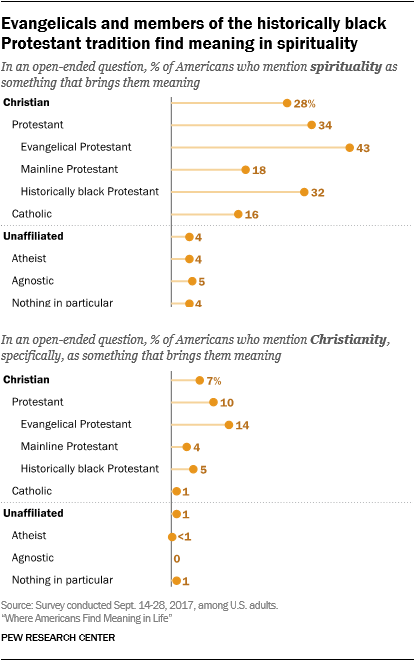

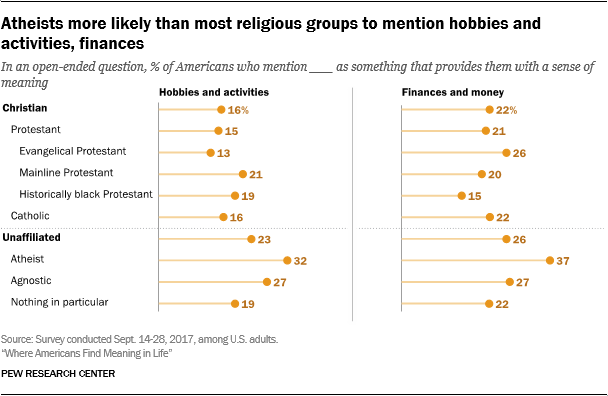

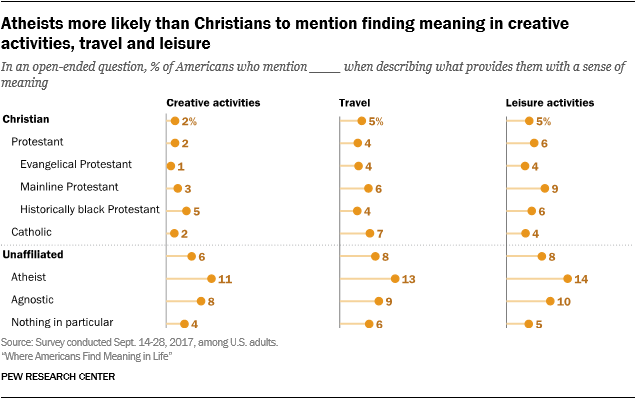

- Many evangelicals find meaning in faith, while atheists often find it in activities and finances. Spirituality and religious faith are particularly meaningful for evangelical Protestants, 43% of whom mention religion-related topics in the open-ended question. Among members of the historically black Protestant tradition, 32% mention faith and spirituality, as do 18% of mainline Protestants and 16% of Catholics. Evangelical Protestants’ focus on religious faith also emerges in the closed-ended survey: 65% say it provides “a great deal” of meaning in their lives, compared with 36% for the full sample. At the other end of the spectrum, atheists are more likely than Christians to mention finances (37%), and activities and hobbies (32%), including travel (13%), as things that make their lives meaningful. Atheists tend to have relatively high levels of education and income, but these patterns hold even when controlling for socioeconomic status.

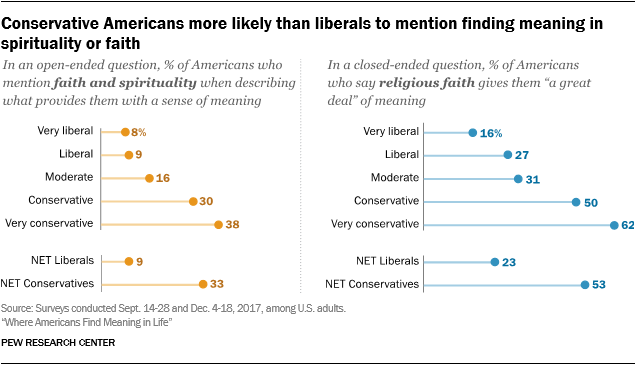

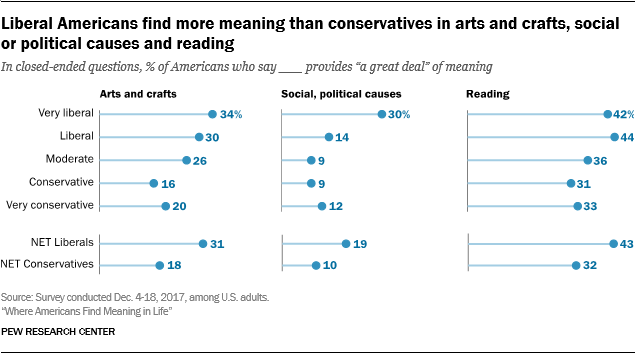

- Politically conservative Americans are more likely than liberals to find meaning in religion, while liberals find more meaning in creativity and causes than do conservatives. Spirituality and faith are commonly mentioned by very conservative Americans as imbuing their lives with meaning and fulfillment; 38% cite it in response to the open-ended question, compared with just 8% of very liberal Americans – a difference that holds even when controlling for religious affiliation. By contrast, the closed-ended question finds that very liberal Americans are especially likely to derive “a great deal” of meaning from arts or crafts (34%) and social and political causes (30%), compared with rates of 20% and 12% among very conservative Americans.

Measuring meaning

The closed-ended questions were included in a survey conducted Dec. 4 to 18, 2017, among 4,729 U.S. adults on Pew Research Center’s nationally representative American Trends Panel. Respondents were asked to indicate how much meaning and fulfillment they derive (“a great deal,” “some,” “not much” or “none at all”) from each of 15 possible sources. Additionally, respondents were asked to indicate which of the 15 items provides them with the most meaning and fulfillment. (For details on how the December survey was conducted, including full question wording, see Appendix B in “The Religious Typology.”)

The open-ended question was included in a survey conducted Sept. 14 to 28, 2017, among 4,867 U.S. adults on the American Trends Panel.1 The question asked, “We’re interested in exploring what it means to live a satisfying life. Please take a moment to reflect on your life and what makes it feel worthwhile – then answer the question below as thoughtfully as you can. What about your life do you currently find meaningful, fulfilling or satisfying? What keeps you going, and why?”

Those answering the question were free to write as much as they wanted. The average respondent wrote 41 words; some wrote hundreds of words. Respondents who gave longer responses tend to be highly educated and are more likely to be women. The patterns highlighted in this report hold up even when controlling (in multiple regression models) for the length of the responses as well as the demographic characteristics of respondents.

Researchers used natural language processing methods and human validation to identify topics in the open-ended responses. Put more simply, algorithms were used to analyze the responses for specific terms, and researchers verified the results to ensure accuracy. The goal was to classify whether each response mentions a given topic. Using a computational model of words that regularly appear together in the answers, researchers identified 30 different topics and used sets of keywords to measure each topic and label the responses. For example, answers that used words like “reading” and “exercise” were classified as mentioning “activities and hobbies.” Responses could be coded as mentioning multiple topics or none at all. For example, responses that mentioned “reading the Bible” were identified as both mentioning reading as an activity or hobby, and Christianity, faith and spirituality.

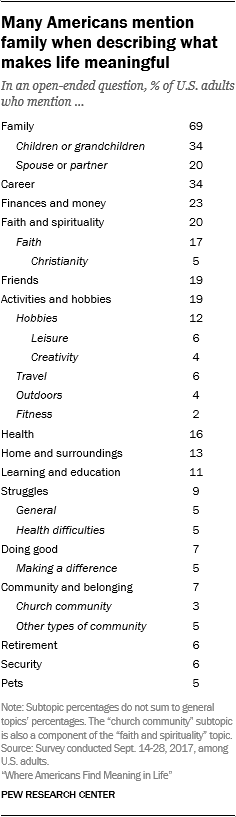

The open-ended responses include both broad topics and more specific subtopics within them. For example, respondents who specifically mention their husband, wife or romantic partner are coded as having cited a spouse or partner (20%). Those who respond with specific mention of their children or grandchildren (34%) are coded as such. And all respondents who mention any of these are also included in a broader category of those who mention family (69%), as are those who use words like “mom,” “sibling,” “niece” or simply “family.”

Similarly, responses that contain words like “Jesus” or “Christian” are included in the Christianity category (5%). The category of those who mention faith and spirituality (20% of all respondents) includes the 5% who mention Christianity as well as those who mention other religions or offer more general references with words like “God,” “religion,” “creator,” or simply “faith” or “spirituality.”

Full details about how the open-ended responses were coded are provided in the Methodology.

In many cases, the results of the open-ended and closed-ended questions resemble one another. For instance, 69% of respondents mention something having to do with family in their open-ended response to the question of what gives their life meaning and satisfaction, and an identical share (69%) say in the closed-ended question that they derive “a great deal” of meaning and fulfillment from family. Similarly, career is mentioned as a source of meaning and fulfillment by one-third of respondents in both the open-ended and the closed-ended questions.

In other cases, however, the two approaches to asking the question about what makes life meaningful yield very different results – at least at first glance. For example, in the open-ended question, just 5% of respondents mention something about pets or animals when describing what makes their lives meaningful. But in the closed-ended question, fully 45% of Americans say “caring for pets” provides them with “a great deal” of meaning and fulfillment.

These divergent results underscore the very different nature of the two kinds of questions. The results of the open-ended question suggest that when asked to describe, in their own words, what provides them with meaning and fulfillment and satisfaction in life, relatively few people think immediately of pets or caring for animals. Other things – including family, friends, career and religious faith – may come to mind much more quickly for most people.

However, when prompted explicitly in the closed-ended question to think about their pets, nearly half of Americans acknowledge that caring for their animals does, indeed, provide them with a great deal of meaning and fulfillment, and an additional three-in-ten say they get “some” meaning and fulfillment from their relationships with animals.

The surveys find similar patterns with respect to being outdoors and experiencing nature, fitness activities, and creative hobbies (such as arts and crafts or making music). These are all cited as providing a great deal of meaning by much larger shares of respondents when they are reminded about them in the closed-ended question than when they are asked to express, in their own words, what makes their lives meaningful and fulfilling.

The open-ended responses were coded using a computer-assisted approach in which certain keywords were identified as indicators of particular sources of meaning or fulfillment. For the most part, the interpretation of responses including these keywords is straightforward because respondents were referring to topics in an overwhelmingly positive way. Responses containing words like “Jesus,” “Christ” or “Bible” are clearly indicative of respondents who find meaning in Christianity, and those containing phrases like “traveling” and “exploring the world” are indicative of respondents who enjoy traveling. The keywords related to security and stability also conveyed something respondents feel positive about, rather than something they lack. Similarly, the words used to discuss being in good health were distinct enough from those used to discuss health difficulties and medical issues that researchers were able to measure both concepts with two different sets of keywords.

But the language surrounding other topics was more nuanced, making the interpretation of some kinds of responses more ambiguous. For instance, all responses that included any of a dozen words related to money or finances (e.g., “money,” “pay” or “paid,” “income,” “afford,” “salary,” “finance” or “financially,” etc.) were coded as having mentioned money, regardless of context, since the computer-assisted coding approach was unable to distinguish whether the keywords were used in a positive or negative sense. Human coding conducted by researchers found that most such responses (77% of all responses coded as having referenced money) mention money in a positive sense. For instance, one respondent finds life meaningful in part because, “[I have] an interest in my chosen career and I expect to be well paid for it in coming years.” But others (23% of all responses that mention money) discuss money in a more neutral way (like the respondent who said, “I think life is more than wealth in money”) or in a negative context (like the respondent who indicated she finds meaning in her faith despite the fact that she has “a very difficult time financially”).

However, in bringing up each topic, respondents are indicating that these factors affect their sense of meaning in some way. Mentions of specific topics should be interpreted as things that pertain to or affect a respondent’s sense of meaning or satisfaction in life, but it is also important to keep in mind that not all mentions of the topic are necessarily positive or refer to respondents’ current feelings (as opposed to the way they felt at some point in the past).

Different groups of Americans find meaning in different places

Different groups of Americans mention different topics when asked what gives them meaning in life. Those with high income levels are more likely to mention friends and being in good health. Evangelical Protestants are more likely than Christians in general to say that they find a great deal of meaning in religion. Those who identify as politically liberal mention creative activities more than Americans overall, while conservatives are more likely to bring up faith, even after controlling for differences in their religious identification. For the most part, these and other patterns are observed in both the open-ended and closed-ended questions (where direct comparisons are possible).

Americans with higher household income, more education are most likely to mention friendships, good health, stability

There are several sources of meaning that are mentioned much more often by Americans with high incomes and levels of educational attainment than by those with lower incomes and less education. For instance, the open-ended question finds that higher levels of education and income are associated with an increased likelihood that a respondent will cite friendships and good health. Furthermore, high levels of education also are associated with mentioning a sense of security or stability and recreational activities as key sources of meaning and fulfillment.

There are several sources of meaning that are mentioned much more often by Americans with high incomes and levels of educational attainment than by those with lower incomes and less education. For instance, the open-ended question finds that higher levels of education and income are associated with an increased likelihood that a respondent will cite friendships and good health. Furthermore, high levels of education also are associated with mentioning a sense of security or stability and recreational activities as key sources of meaning and fulfillment.

Conversely, there are few topics that those with lower levels of income and education mention more often than others. Taken together, these findings suggest that those respondents who are socioeconomically advantaged may have resources – like free time to spend with friends or money to pursue opportunities to travel – that those who are less socioeconomically privileged simply do not have.

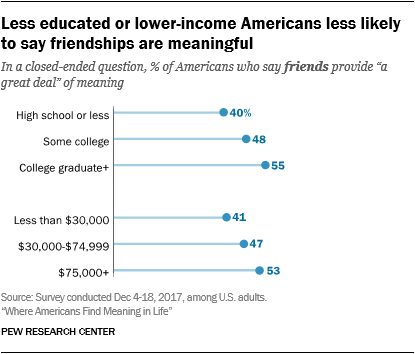

For example, those with a college degree are more likely than those with a high school diploma or less education to mention their friends (29% vs. 12%). There is a similar gap across income groups, even after accounting for education: A quarter of those who earn more than $75,000 a year mention friends, compared with 14% of those who have household incomes of less than $30,000 a year. One respondent in the highest income and education groups said: “Enjoying being with friends and family. What keeps me going is gourmet cooking for my friends and family.”

For example, those with a college degree are more likely than those with a high school diploma or less education to mention their friends (29% vs. 12%). There is a similar gap across income groups, even after accounting for education: A quarter of those who earn more than $75,000 a year mention friends, compared with 14% of those who have household incomes of less than $30,000 a year. One respondent in the highest income and education groups said: “Enjoying being with friends and family. What keeps me going is gourmet cooking for my friends and family.”

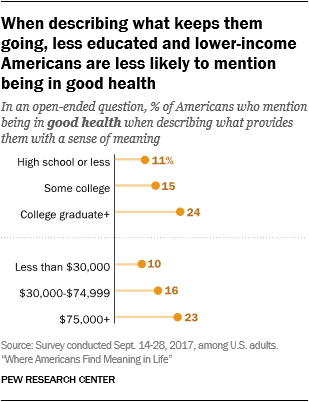

Education and income also are associated with whether respondents mention the health of themselves or loved ones. About a quarter of college graduates (24%) and those with household incomes of $75,000 or more (23%) mention being in good health when describing what gives them a sense of meaning. For instance, one respondent at the highest income and education levels said, “I am strong and fit, and while I am facing the physical changes that you face as you age, I am doing what can be done to defer them.” In contrast, those with incomes under $30,000 and those with no college experience are less likely to mention the topic (10% and 11%, respectively).

Education and income also are associated with whether respondents mention the health of themselves or loved ones. About a quarter of college graduates (24%) and those with household incomes of $75,000 or more (23%) mention being in good health when describing what gives them a sense of meaning. For instance, one respondent at the highest income and education levels said, “I am strong and fit, and while I am facing the physical changes that you face as you age, I am doing what can be done to defer them.” In contrast, those with incomes under $30,000 and those with no college experience are less likely to mention the topic (10% and 11%, respectively).

In addition to being less likely to mention being in good health, Americans whose household incomes are below $30,000 are somewhat more likely than those who earn $75,000 or more to mention health difficulties (coded as a different topic) as part of their response to the open-ended question about what makes their life meaningful. As one lower-income respondent put it, “It’s been more than difficult. Every year I’ve needed surgery on something. I’m still striving to do my best, to live my most productive life.”

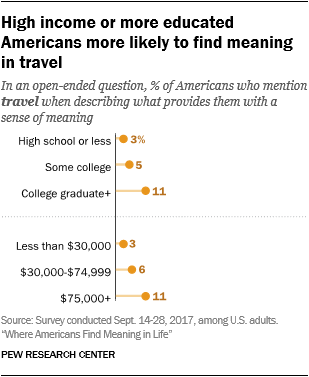

Travel is also mentioned more frequently by those with high household incomes, as well as those with college degrees – 11% in both groups bring up traveling, exploring new places, or going on vacation, compared with 3% of those with no college experience or incomes under $30,000. As one low-income college-educated respondent put it, “I travel to see friends and family. I live in a beautiful country where I can see, hear and appreciate God’s creation.” On the other hand, one high-income person with no college experience echoed similar sentiments: “Traveling and seeing things I have never seen, enjoying simple things like the outdoors and warm weather.”

Those with higher incomes or college experience are also far more likely to mention their job or career when describing what gives them a sense of meaning. Nearly half – 48% – of both high-income and college-educated Americans mention their job. By contrast, just 24% of those without college experience and 22% of those making less than $30,000 cite their job or career when discussing how they find meaning and satisfaction in life.2

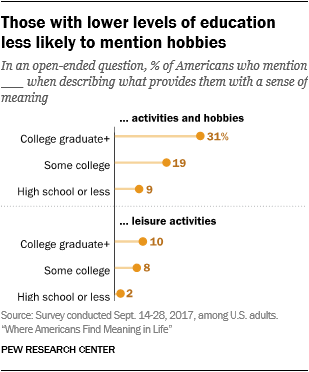

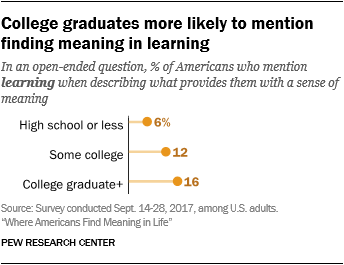

Levels of education – but not income – have a strong relationship with finding meaning in personal activities and hobbies, as well as other broad topics like feeling a sense of security and stability, and learning or education itself. College graduates are about three times as likely as Americans with less education to mention activities of any kind (31% among college graduates, compared with just 9% of those with no college experience). In particular, they more frequently cite leisure activities (10%, compared with 2% among those with a high school degree or less). Those with college or graduate degrees also are more likely to mention learning or education when describing what gives them a sense of meaning (16% vs. 6% of Americans with a high school degree or less). For example, one respondent with a college degree said, “I’m a gardener and use cover crops to increase soil tilth and fertility. This requires that I continue to explore and learn about the soil ecosystem.”

Levels of education – but not income – have a strong relationship with finding meaning in personal activities and hobbies, as well as other broad topics like feeling a sense of security and stability, and learning or education itself. College graduates are about three times as likely as Americans with less education to mention activities of any kind (31% among college graduates, compared with just 9% of those with no college experience). In particular, they more frequently cite leisure activities (10%, compared with 2% among those with a high school degree or less). Those with college or graduate degrees also are more likely to mention learning or education when describing what gives them a sense of meaning (16% vs. 6% of Americans with a high school degree or less). For example, one respondent with a college degree said, “I’m a gardener and use cover crops to increase soil tilth and fertility. This requires that I continue to explore and learn about the soil ecosystem.”

College-educated Americans also are more likely to mention having a sense of security or stability. One-in-ten of those with college degrees (11%) say they derive meaning from a sense of security, compared with just 2% of those without any college experience – regardless of their age or income. One respondent who has a postgraduate degree said, “Being safe and secure. Knowing that my family will be taken care of and having their needs met. My children having a future as bright as mine.”

College-educated Americans also are more likely to mention having a sense of security or stability. One-in-ten of those with college degrees (11%) say they derive meaning from a sense of security, compared with just 2% of those without any college experience – regardless of their age or income. One respondent who has a postgraduate degree said, “Being safe and secure. Knowing that my family will be taken care of and having their needs met. My children having a future as bright as mine.”

Like the open-ended question, the closed-ended questions find that those with more socioeconomic resources may have more opportunities for social activities than those who have fewer resources. For example, 55% of college graduates say spending time with friends provides them with “a great deal” of meaning and fulfillment, compared with 40% of those with a high school degree or less. Similarly, more than half (53%) of those with household incomes above $75,000 a year say that friends provide them with “a great deal” of meaning, while only 41% of those with incomes under $30,000 say the same.

Like the open-ended question, the closed-ended questions find that those with more socioeconomic resources may have more opportunities for social activities than those who have fewer resources. For example, 55% of college graduates say spending time with friends provides them with “a great deal” of meaning and fulfillment, compared with 40% of those with a high school degree or less. Similarly, more than half (53%) of those with household incomes above $75,000 a year say that friends provide them with “a great deal” of meaning, while only 41% of those with incomes under $30,000 say the same.

However, while education and income are associated with whether respondents mention their job or career in the open-ended question, these factors have no substantial effect on whether Americans say in the closed-ended question that they draw “a great deal” of meaning from their job or career. This suggests that those with higher incomes or more education do not necessarily find more meaning in their jobs, but that they are notably more likely to think of and bring up their careers when asked to describe in their own words what gives them a sense of meaning in their lives.

However, while education and income are associated with whether respondents mention their job or career in the open-ended question, these factors have no substantial effect on whether Americans say in the closed-ended question that they draw “a great deal” of meaning from their job or career. This suggests that those with higher incomes or more education do not necessarily find more meaning in their jobs, but that they are notably more likely to think of and bring up their careers when asked to describe in their own words what gives them a sense of meaning in their lives.

Where different racial groups find meaning

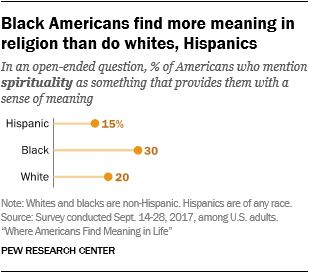

Regardless of their particular religious denomination, black Americans are more likely than others to mention faith and spirituality when describing (in the open-ended question) what gives them a sense of meaning.3 Fully three-in-ten black Americans (30%) mention spirituality and faith, compared with 20% of whites and 15% of Hispanics.

Regardless of their particular religious denomination, black Americans are more likely than others to mention faith and spirituality when describing (in the open-ended question) what gives them a sense of meaning.3 Fully three-in-ten black Americans (30%) mention spirituality and faith, compared with 20% of whites and 15% of Hispanics.

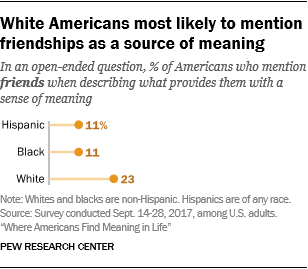

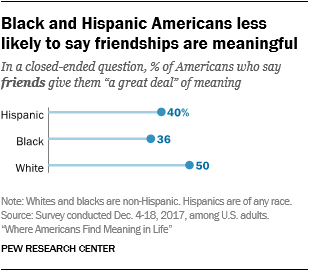

Race and ethnicity also are linked with a number of other sources of meaning, independent of socioeconomic factors. Specifically, white Americans are much more likely than black and Hispanic Americans to mention friends, stability and security, and a positive home environment as sources of meaning in their lives, even when controlling for education and income.

Race and ethnicity also are linked with a number of other sources of meaning, independent of socioeconomic factors. Specifically, white Americans are much more likely than black and Hispanic Americans to mention friends, stability and security, and a positive home environment as sources of meaning in their lives, even when controlling for education and income.

While 23% of white Americans mention friends when describing what gives their lives meaning, fewer black and Hispanic Americans do so (11% in each group). Furthermore, black and Hispanic Americans are much less likely than whites to mention enjoying where they live; 5% and 7% do so, compared with 16% of white Americans. And while 13% of blacks and 14% of Hispanics mention finances and money in some way, more white Americans (26%) mention the topic when describing what makes their lives meaningful.4

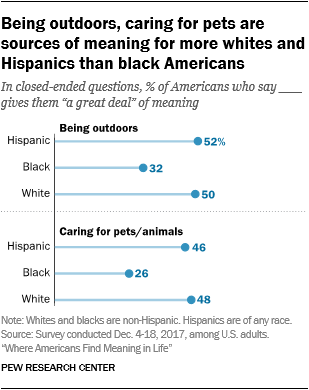

Analysis of the open-ended responses also shows that black Americans are less likely than others to mention being in good health (8%, compared with 15% of Hispanics and 18% of whites), and black Americans are notably less likely than whites to mention pets or animals or enjoying the outdoors and nature. While these topics were not brought up frequently in the open-ended responses by any group, hundreds of white respondents mentioned pets or animals and nature or the outdoors. In contrast, fewer than 10 black respondents mentioned either topic.

Analysis of the open-ended responses also shows that black Americans are less likely than others to mention being in good health (8%, compared with 15% of Hispanics and 18% of whites), and black Americans are notably less likely than whites to mention pets or animals or enjoying the outdoors and nature. While these topics were not brought up frequently in the open-ended responses by any group, hundreds of white respondents mentioned pets or animals and nature or the outdoors. In contrast, fewer than 10 black respondents mentioned either topic.

Similar patterns are found in the closed-ended questions, in which fully half of black Americans (52%) say they derive “a great deal” of meaning from their religion, compared with 37% of Hispanic Americans and a third of white Americans. Furthermore, a third of black Americans (32%) indicate that religion is their single most important source of meaning in life, compared with 18% of whites and 16% of Hispanics.

Similar patterns are found in the closed-ended questions, in which fully half of black Americans (52%) say they derive “a great deal” of meaning from their religion, compared with 37% of Hispanic Americans and a third of white Americans. Furthermore, a third of black Americans (32%) indicate that religion is their single most important source of meaning in life, compared with 18% of whites and 16% of Hispanics.

The closed-ended survey also finds that both black and Hispanic Americans are less likely than whites to say that spending time with friends provides them with “a great deal” of meaning. And whereas about half of Hispanics and whites say they get “a great deal” of meaning from pets or spending time in nature, just a quarter of black respondents say they get “a great deal” of meaning from pets (26%), and one-third say the same about nature (32%).

Among evangelicals, religion ranks as the most important source of meaning

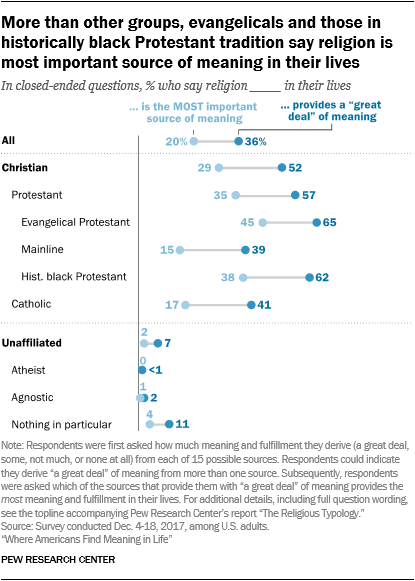

Religion is not the most commonly referenced source of meaning and fulfillment in either survey. In the open-ended question, one-in-five adults mention spirituality and religious faith when describing the things they find meaningful and fulfilling, which is on par with the share who mention friends and various activities or hobbies. And in the closed-ended question, 36% of those surveyed say they get “a great deal” of meaning and fulfillment from their religious faith, which is roughly equivalent to the share who draw the same level of meaning from reading or from their career.

But while religion is not a universal source from which Americans say they obtain “a great deal” of meaning, it is a highly salient source of fulfillment among those who select it. Indeed, among those who say (in the closed-ended survey) that religion provides them with “a great deal” of meaning, 55% say that religion is their most important source of meaning, while fewer (30%) say family provides them with the most meaning and fulfillment.

But while religion is not a universal source from which Americans say they obtain “a great deal” of meaning, it is a highly salient source of fulfillment among those who select it. Indeed, among those who say (in the closed-ended survey) that religion provides them with “a great deal” of meaning, 55% say that religion is their most important source of meaning, while fewer (30%) say family provides them with the most meaning and fulfillment.

For members of some religious traditions as well – particularly evangelical Protestants and members of the historically black Protestant tradition – faith matches or exceeds anything else as the top source of meaning and fulfillment. About two-thirds (65%) of evangelical Protestants say they find “a great deal” of meaning in their religious faith, including 45% who say religion is the most important source of meaning in their lives – higher than the share who say this about family (31%). A similar share of those in the historically black Protestant tradition (62%) also report that their religious faith provides them with “a great deal” of meaning, including 38% who say religion is the most important source of meaning in their lives.

For members of some religious traditions as well – particularly evangelical Protestants and members of the historically black Protestant tradition – faith matches or exceeds anything else as the top source of meaning and fulfillment. About two-thirds (65%) of evangelical Protestants say they find “a great deal” of meaning in their religious faith, including 45% who say religion is the most important source of meaning in their lives – higher than the share who say this about family (31%). A similar share of those in the historically black Protestant tradition (62%) also report that their religious faith provides them with “a great deal” of meaning, including 38% who say religion is the most important source of meaning in their lives.

By comparison, roughly four-in-ten Catholics (41%) and mainline Protestants (39%) say their religious faith provides them with “a great deal” of meaning and fulfillment. Also, in contrast with evangelical Protestants and members of the historically black Protestant tradition, fewer Catholics and mainline Protestants say religion is the most important source of meaning in their lives (17% and 15%, respectively). Instead, they are among the most likely of all religious groups to say that family provides them with the most meaning (50% and 54%, respectively).

In the open-ended question, too, evangelical Protestants are more likely than other Americans to mention faith and spirituality (and Christianity, specifically) when asked what makes life meaningful. Overall, 43% of evangelicals mention spirituality or faith in some way, including 14% who make specific references to their Christian faith. For example, one evangelical respondent said, “My belief in Jesus Christ and his teachings helps me greatly when things get really difficult.”

Spirituality is also a commonly mentioned topic among those in the historically black Protestant tradition, among whom 32% mention spirituality or faith as a source of meaning in their lives. Smaller shares of mainline Protestants (18%) and Catholics (16%) mention faith and spirituality as sources of meaning and fulfillment.

Spirituality is also a commonly mentioned topic among those in the historically black Protestant tradition, among whom 32% mention spirituality or faith as a source of meaning in their lives. Smaller shares of mainline Protestants (18%) and Catholics (16%) mention faith and spirituality as sources of meaning and fulfillment.

Not surprisingly, very few self-described atheists mention spiritual topics when asked what makes life meaningful. Instead, atheists are much more likely than others to mention finances or involvement in various kinds of activities. Indeed, roughly a third of atheists (37%) discuss finances in response to the open-ended question, compared with 26% among evangelical Protestants, 22% among Catholics, 20% among mainline Protestants and 15% among those in the historically black Protestant tradition. One atheist described finding meaning in “doing work and acting in a way that is meaningful to your beliefs. Being financially comfortable to be able to do things that make you happy.”

Atheists are especially likely to mention hobbies and activities in general – roughly a third (32%) of atheists do so. In particular, they are more likely than Americans overall to mention creative activities like painting and writing, leisure activities like playing games and watching movies, and traveling or exploring new places as sources of meaning and fulfillment in their lives. For example, one said, “I also find a lot of pleasure in trying new things, athletics, and exploration. I have the money and the flexible schedule to go on adventures and challenge myself physically.”

Conservative Americans more likely to find meaning in religion, while liberal Americans more likely to find meaning in creativity and social causes

Americans who identify as conservative or very conservative are more likely than others to say they find “a great deal” of meaning in their religious faith, while those who are liberal or very liberal are more likely than conservatives to say they find a great deal of meaning in arts and crafts and social or political causes.

Regardless of their religious affiliation, conservative or very conservative Americans are more likely than liberals to mention (in their open-ended responses) their spirituality or faith as a key source of meaning in their lives (33% vs 9%). As one conservative respondent said, “First, my life is rooted in God and the knowledge that He provides unconditional love and support regardless of what is happening in the world. With God at the center of my life, circumstances may change but love, peace, and joy remain.”

The closed-ended question echoes this pattern. Conservative U.S. adults are at least twice as likely as liberals to say religion provides them with “a great deal” of meaning (53% vs 23%). This is especially true of very conservative Americans: Six-in-ten (62%) say their religious faith provides them with “a great deal” of meaning, including 41% who say that it is their most important source of meaning. In contrast, just 16% of very liberal Americans say that they find “a great deal” of meaning in religion, including just 5% who say that it provides them with the most meaning in life. And fully half of very liberal Americans report that religion does not contribute at all to their sense of meaning.

Liberals, meanwhile, are more likely than conservatives to say they derive meaning and fulfillment from listening to music and arts and crafts. Fully half of liberals say they get “a great deal” of meaning from listening to music (52%), and three-in-ten (31%) say they get “a great deal” of meaning from arts and crafts. By comparison, 34% of conservatives derive “a great deal” of meaning from listening to music, and 18% say the same about arts and crafts. These results come from the closed-ended question, but as one self-identified liberal put it in responding to the open-ended question, “Art and love keep me going. I am in a relationship with the love of my life again, and he encourages me to follow my heart and pursue whatever art it is I want to follow at the time. I paint, draw, do photography, make jewelry, do paper crafts, small woodworking and wood burning, sew costumes and other clothing, blend spices, dry flowers, and sometimes do projects that might be called ‘fusion’ art, such as painting and adding pieces of paper crafts.”

Liberal Americans are also more likely than conservatives to say that social or political causes provide them with “a great deal” of meaning (19% vs. 10%). And among those identifying as “very liberal,” three-in-ten (30%) say they find a great deal of meaning in social or political causes, almost three times the rate seen in the general public. In the open-ended question, one very liberal respondent said they find meaning in “volunteering for causes I believe in like ending hunger and social justice issues,” among other activities. Liberals are also notably more likely to say that they find “a great deal” of meaning in reading: Four-in-ten say they do (43%), compared with 37% of Americans overall.

Younger Americans less likely to mention religion, but draw more meaning from learning than older Americans

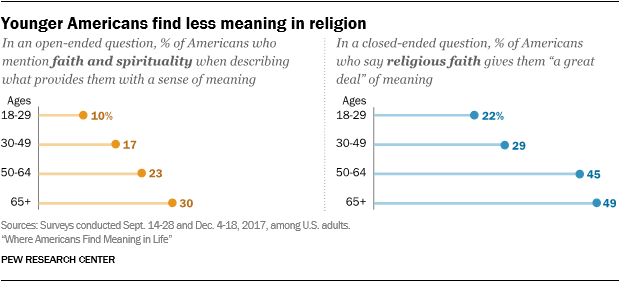

Just 10% of U.S. adults under age 30 mention spirituality, faith or God when describing (in the open-ended question) what affects their sense of meaning. By contrast, three-in-ten adults ages 65 and older mention religion when describing what makes their life meaningful and fulfilling.

The closed-ended question finds a similar relationship between age and finding meaning in religion: Roughly one-in-five adults under 30 (22%) report that religion provides them with “a great deal” of meaning, while fully a third (34%) say religion provides them with no meaning at all. By contrast, half of those ages 65 or older report that they draw “a great deal” of meaning from religion, and only 12% say they do not get any meaning and fulfillment from religion. Three-in-ten (29%) of those ages 65 or older say religion is the top source of meaning in their lives, while 10% of adults under 30 say the same.

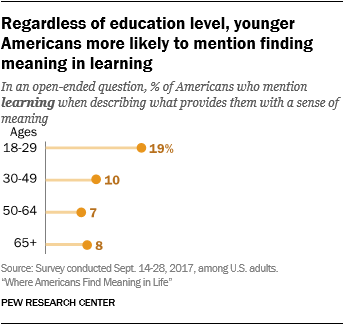

Meanwhile, U.S. adults under age 30 are more likely than older Americans to say (in the open-ended question) that they find meaning in learning or education (19% do so, compared with 9% among older Americans). This difference between younger and older adults is statistically significant even accounting for different levels of educational attainment between the groups, although it may be connected to the fact that a much higher share of young adults are current or recent full-time students.

Meanwhile, U.S. adults under age 30 are more likely than older Americans to say (in the open-ended question) that they find meaning in learning or education (19% do so, compared with 9% among older Americans). This difference between younger and older adults is statistically significant even accounting for different levels of educational attainment between the groups, although it may be connected to the fact that a much higher share of young adults are current or recent full-time students.

Married Americans more likely to mention family, religion

While family is a key source of meaning for Americans in many different demographic categories, there are some variations between subgroups. For example, women are somewhat more likely than men to say family provides a great deal of meaning in their lives.

While family is a key source of meaning for Americans in many different demographic categories, there are some variations between subgroups. For example, women are somewhat more likely than men to say family provides a great deal of meaning in their lives.

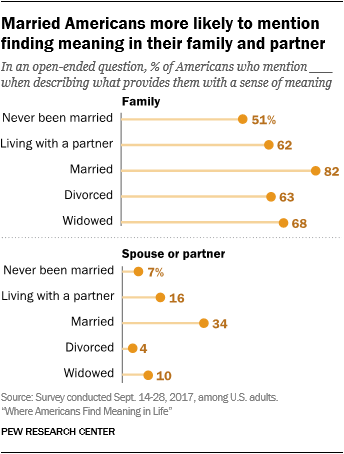

When asked in the open-ended question about what gives them a sense of meaning and satisfaction in life, married Americans are more likely than unmarried people to mention family (which includes specific references to one’s spouse or children). Four-in-five married people (82%) mention family as a source of meaning and fulfillment (including 34% who specifically mention their spouse or partner), compared with 59% of unmarried U.S. adults. Married Americans are also more likely to mention spirituality or faith; 23% do, compared with 13% of Americans that have never been married.

Similar patterns emerge in the closed-ended question. Married Americans are more likely than unmarried people to say that family provides them with “a great deal” of meaning (80% vs. 60%). And half (49%) say that it is their most important source of meaning, compared with 32% of unmarried Americans. Married people also are more likely than unmarried people to indicate that they find “a great deal” of meaning in religion (41% vs. 32%), and a quarter (24%) say religion is the most important source of meaning in their lives, compared with 16% among unmarried Americans. One married American explained that they find meaning in “association with family and friends. … The relationship I share with my wife. But most of all, my relationship with my Lord and Savior Jesus Christ.”