Overall, some groups of Americans are far better at parsing through news content than others, suggesting gaps in the public’s competence. Most prominently, Americans’ familiarity with politics and the digital world bleeds into how they understand statements in the news. Those with high political awareness (those who are both knowledgeable about politics and regularly get political news) and high digital savviness (those who say they are highly capable of using digital devices and regularly use the internet) are much more likely to know the difference between factual and opinion news statements. Likewise, Americans with a lot of trust in national news organizations have an easier time separating factual from opinion statements than those with less trust. How closely one follows the news, on the other hand, provides only a modest edge in classifying factual statements, but not opinions.

Even though these characteristics relate in predictable ways to education, these relationships hold true even when accounting for level of education.7 Further, there is relatively modest overlap among the groups, meaning that each of these groups is distinct.8 For example, just 32% of those with high political awareness also have a lot of trust in national news organizations. The group that shows the largest overlap with the other groups is those who are very digitally savvy, since they account for a large portion of the population generally (48%), but even here the overlap with the other groups never reaches more than 58%.

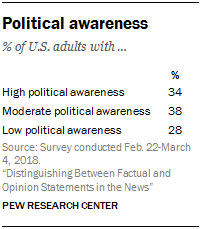

- Politi

cal awareness is the measure of knowledge of and interest in politics and government and is based on the combined responses in two separate areas:

cal awareness is the measure of knowledge of and interest in politics and government and is based on the combined responses in two separate areas:

- Correctly answering three political knowledge questions (e.g., “Who is Mike Pence?”; see topline for all items)

- Including government and politics among the topics one regularly gets news about

Those with high political awareness both answer all three knowledge questions correctly and regularly get news about government and politics; for those with moderate political awareness, only one of these two is the case; and for those with low political awareness, neither is the case.

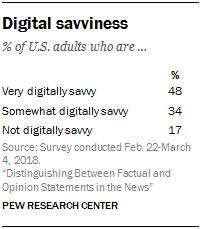

- Digital savviness is the measure of use of and familiarity with digital technology and is based on responses to two separate indicators:

- Reporting using the internet at least multiple times a day

- Being very confident in one’s ability to use electronic devices

Those who are very savvy both use the internet multiple times a day and are very confident in their ability to use digital devices; for those who are somewhat savvy, only one of these is the case; and for those who are not savvy, neither is the case.

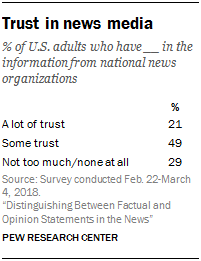

Trust in news media is a measure based on the response to a single question: “How much, if at all, do you trust the information you get from national news organizations?” Respondents were divided into those who answered “a lot”; those who answered “some”; and those who answered either “not too much” or “none at all.”

Trust in news media is a measure based on the response to a single question: “How much, if at all, do you trust the information you get from national news organizations?” Respondents were divided into those who answered “a lot”; those who answered “some”; and those who answered either “not too much” or “none at all.”

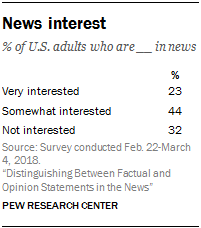

- News interest is a measure of interest in news more broadly and is based on the combined responses to two indicators:

- Following the news “most of the time, whether or not something important is happening” (rather than “only when something important is happening”)

- Responding that getting the news is one of the three activities, among a list of six, done most frequently during one’s free time

Those who are very interested both follow the news most of the time and list getting the news as one of their most frequent leisure activities; for those who are somewhat interested, only one of these two is the case; and for those who are not interested, neither is the case.

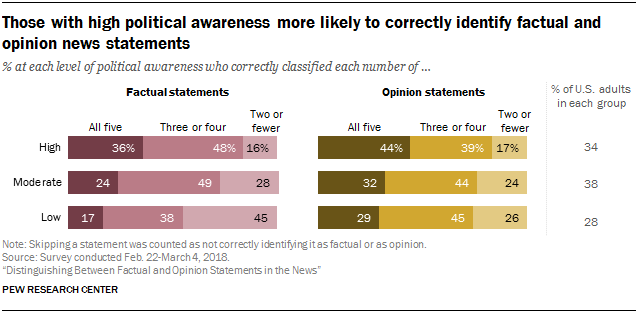

Those with high political awareness are far better able to identify factual and opinion statements

Those with high political awareness show far greater ability to correctly identify both factual and opinion statements. About a third (36%) correctly identified all five factual statements as factual, compared with 17% of those with low political awareness. Those with moderate awareness fell in between the two at 24%.

What’s more, just under half of those with low political awareness (45%) accurately classified two or fewer of the factual statements, misclassifying more than half of them. This was true of just 16% of those with high awareness.

A similar pattern emerges for correctly identifying all five of the opinion statements, which 44% of those with high political awareness, 29% of those with low awareness and 32% of those in between could do. The most politically aware were also more likely to see both borderline statements as opinions than those with moderate or low awareness, which is in line with people overall considering these statements to be opinions.

While some groups did fare better than others, overall, there was no group where a majority classified all five factual or opinion statements correctly.

In this study, political awareness measures how politically knowledgeable someone is and how often he or she gets news about government and politics. Those with high political awareness are both highly knowledgeable (accurately answering three political knowledge items) and report regularly getting political news. About a third of Americans (34%) have high political awareness, about four-in-ten (38%) have moderate awareness and 28% have low awareness.

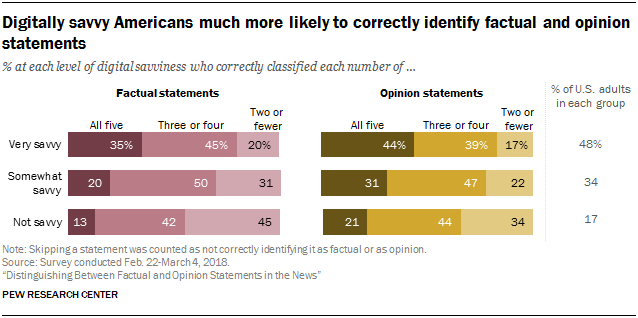

Digitally savvy Americans fare far better at classifying factual and opinion statements

The very digitally savvy are also notably better at classifying statements as factual or opinion, with the divide between the very digitally savvy and those who are not savvy standing out as particularly stark. Roughly three times as many very digitally savvy (35%) as not savvy Americans (13%) classified all five factual statements correctly, with the somewhat savvy falling in between (20%). And about twice as many classified all five opinion statements correctly (44% of the very digitally savvy versus 21% of the not digitally savvy).

Like those with low political awareness, just under half of the not digitally savvy (45%) correctly classified two or fewer factual statements, erroneously identifying most as opinions. They were slightly more successful at the opinion statements, with around a third (34%) classifying two or fewer correctly.

Similar to those high in political awareness, those who are very digitally savvy were more likely to categorize both borderline statements as opinions than those who are less savvy.

Digital savviness is based on Americans’ frequency of internet use and confidence in using digital devices. About half (48%) are very digitally savvy (those who use the internet at least multiple times a day and are very confident in using digital devices), while 17% are not savvy (those who use the internet once a day or less and are not very confident in using digital devices). About a third (34%) fall in between the two and are categorized as somewhat digitally savvy.

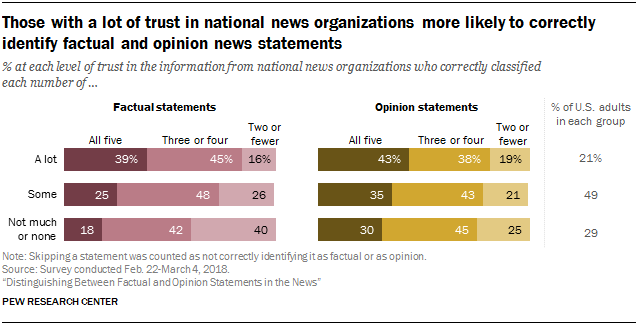

Those with greater trust in the news media are more likely to correctly classify factual and opinion statements

Previous Pew Research Center findings that Americans’ attitudes about the news are strongly related to their news habits are reinforced in this study: Those more trusting of national news organizations are better at accurately categorizing factual and opinion statements.

About four-in-ten of those who have a lot of trust in the information from national news organizations (39%) categorized all five factual statements correctly, about twice the rate of those who have not much or no trust (18%) and also more than those with some trust (25%). Very similar gaps emerge for the opinion statements, declining from 43% among those with a lot of trust down to 30% among those with the least amount of trust. No differences surfaced for the borderline statements.

Likewise, looking at other news attitudes also measured in this survey, such as skepticism toward news and connection to news outlets, found that those who are less skeptical toward the news media were more likely to correctly classify both factual and opinion news statements. Respondents who feel a closer connection to their news outlets were more likely to correctly classify the factual statements.

Overall, about one-in-five U.S. adults (21%) has a lot of trust in the information they get from national news organizations, about half (49%) have some trust and 29% have not too much trust or none at all. And while Democrats are more likely than Republicans to trust the news media a lot (35% vs. 12%, respectively), the findings hold true even when accounting for party differences.

The role of education

While those with high political awareness, digital savviness and trust in national news organizations are overall more educated, the findings persist even when accounting for level of education.

As is often seen with survey measures of proficiency, Americans’ level of education makes a difference. Indeed, those with more education are more likely to classify factual and opinion statements correctly, with a magnitude of difference similar to that for political awareness and digital savviness. And given the differences between the very digitally savvy and those less so, it is not surprising that age matters as well, with those ages 18 to 49 being better at classifying statements than those ages 50 and older.9 For a full breakdown, see Appendix B.

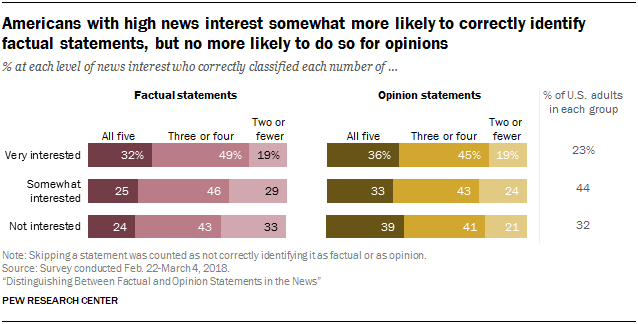

Greater interest in news connects modestly to correct classifications of factual statements; no difference for opinions

In contrast to attitudes about the news, having greater interest in the news is not as closely related to deciphering factual from opinion statements.

Respondents who are the most interested in news were somewhat more likely to correctly identify the factual statements. About a third of the very interested (32%) correctly identified all five factual statements, compared with roughly a quarter of both the least interested (24%) and the somewhat interested (25%). These differences between the high and low groups are notably smaller than for political awareness, digital savviness or trust. And when it comes to opinion statements, there is no clear pattern.

Other measures of news interest asked about in the survey were also only weakly predictive of success in classifying statements. For instance, those who are highly engaged with the news by doing such things as writing letters to the editor, sharing news on social media or performing other actions with the news were more likely than those less engaged to correctly identify the factual statements. This was also true when comparing those who tend to put more consideration into their news (those saying they like to gather additional information about stories they see, debate the news with others and think about the news).

For this study, news interest is based on whether people follow news closely and get news in their free time. Nearly a quarter of Americans (23%) fall into the very interested group, which means they follow news most of the time and say news is one of the top three activities in their free time. About a third (32%) are not interested in news – they follow the news only when something important is happening and do not frequently get news in their free time. The greatest portion (44%) do one or the other but not both and are thus deemed “somewhat interested.”