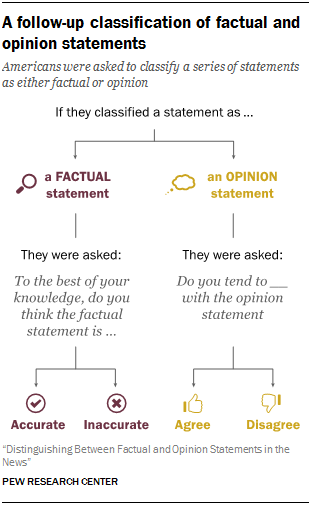

To understand what drives Americans to classify news as either factual or opinion, respondents were asked a follow-up question after each initial response. If they classified a statement as factual, respondents were asked if they thought it was accurate or inaccurate. An opinion classification was followed with a question asking if they agreed or disagreed with the statement.

To understand what drives Americans to classify news as either factual or opinion, respondents were asked a follow-up question after each initial response. If they classified a statement as factual, respondents were asked if they thought it was accurate or inaccurate. An opinion classification was followed with a question asking if they agreed or disagreed with the statement.

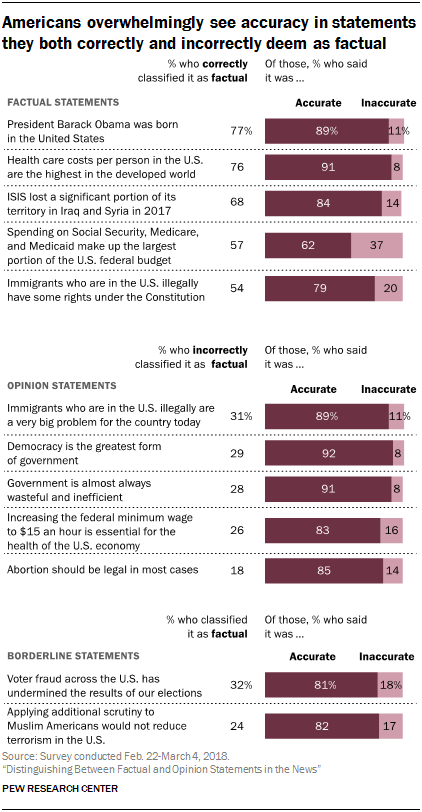

Overall, Americans overwhelmingly tie the idea of news statements being factual with them also being accurate. This is consistent with how the term “facts” is sometimes used in modern political debate – statements that are true. Americans are far less likely to see factual statements as inaccurate – statements that can be disproved based on objective evidence. For both factual statements that people correctly classified and opinion statements that they incorrectly classified as factual, Americans were far more likely to have said each was accurate than inaccurate.

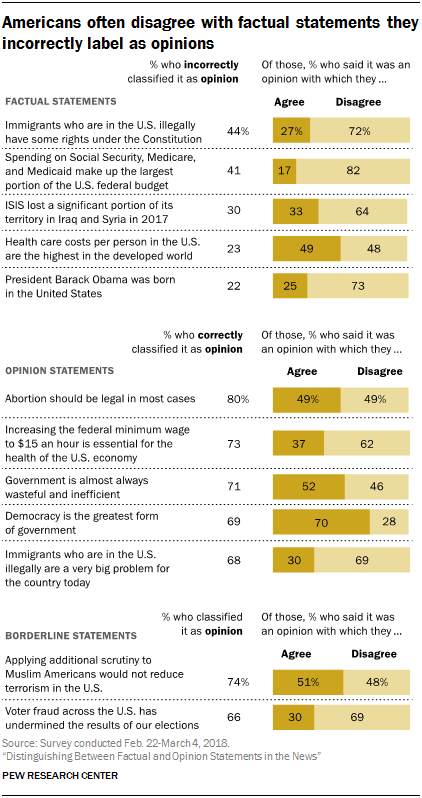

As for opinion statements, correct classifications are not necessarily associated with agreement, but instead result in a mix of agreement and disagreement. However, seeing factual statements as opinions largely coincides with disagreeing with them.

Statements classified as factual are almost always seen as accurate

On the whole, across the factual, opinion and borderline statements, large majorities of those who classified each as factual said it was accurate.

On the whole, across the factual, opinion and borderline statements, large majorities of those who classified each as factual said it was accurate.

All five of the factual statements were accurate, so it makes sense that, overall, large majorities of those who classified each as factual thought it was accurate. For example, 91% of those who correctly identified the statement “Health care costs per person in the U.S. are the highest in the developed world” as factual said it was accurate.

Even when opinion statements were incorrectly classified as factual, large majorities again thought they were accurate, showing that misclassification links to people’s perceptions of their accuracy. At least eight-in-ten of those who identified each of the five opinions as factual statements also said it was accurate. For example, 92% of those who incorrectly classified “Democracy is the greatest form of government” as a factual statement said it was accurate. Likewise, those who classified each borderline statement as factual largely saw accuracy in each.

This does not mean, though, that the public does not ever see a claim in the news as factual and wrong – something that is stated as a fact, but can be unambiguously disproved by objective evidence. Segments of the public – albeit mostly small – classified statements as both factual and inaccurate. For example, a majority of those who correctly classified the statement “Spending on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid make up the largest portion of the U.S. federal budget” as a factual statement saw it as accurate (62%), but roughly four-in-ten (37%) thought it was inaccurate. While the findings do not address how Americans assess inaccurate statements since all of the factual statements included in the study were accurate, this study provides some evidence that Americans can see news as both factual and inaccurate.

Americans most often disagree with factual statements they incorrectly think are opinions

Dissent is a driving factor in why most Americans see factual statements as opinions. In the case of four of the five factual statements, each was largely disagreed with when incorrectly identified as an opinion. For example, 82% of those who incorrectly identified “Spending on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid make up the largest portion of the U.S. federal budget” as an opinion disagreed with it. There was a split between agreeing and disagreeing for only one of the five factual statements when incorrectly classified as an opinion.

Dissent is a driving factor in why most Americans see factual statements as opinions. In the case of four of the five factual statements, each was largely disagreed with when incorrectly identified as an opinion. For example, 82% of those who incorrectly identified “Spending on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid make up the largest portion of the U.S. federal budget” as an opinion disagreed with it. There was a split between agreeing and disagreeing for only one of the five factual statements when incorrectly classified as an opinion.

There was more variation among correctly classified opinion statements. Americans who correctly classified the opinion statement “Democracy is the greatest form of government,” for instance, were more likely to agree (70%) than disagree with it (28%). On the other hand, those who said “Immigrants who are in the U.S. illegally are a very big problem for the country today” were more likely to disagree (69%) than agree with it (30%).

Similar to the opinion statements, there was variation in agreement when borderline statements were classified as opinions. Nearly seven-in-ten (69%) of those who classified the statement “Voter fraud across the U.S. has undermined the results of our elections” as an opinion disagreed with it. However, those who classified “Applying additional scrutiny to Muslim Americans would not reduce terrorism in the U.S.” as an opinion were split between agreeing (51%) and disagreeing (48%).