To shed light on what the cutbacks in Washington-based local newspaper correspondents mean for readers back home, a second part of this study analyzed the federal-government-oriented coverage of eight daily newspapers across the U.S. – four with a Washington correspondent and four without – on all 78 days in which Congress was in session from Feb. 1 through May 31, 2015.

One of the starkest findings is the degree to which even in communities where the local paper has a dedicated reporter in D.C., readers receive far more federal government news stories from wire services, other national media or other newsroom staff than from those reporters stationed in D.C. Much of this may be tied to the fact that one D.C. correspondent, no matter how resourceful, could never produce the amount or breadth of reporting that is provided by other sources of coverage that a daily newspaper has to choose from. But the effect of this equation on what a reader is presented with is significant.

One of the starkest findings is the degree to which even in communities where the local paper has a dedicated reporter in D.C., readers receive far more federal government news stories from wire services, other national media or other newsroom staff than from those reporters stationed in D.C. Much of this may be tied to the fact that one D.C. correspondent, no matter how resourceful, could never produce the amount or breadth of reporting that is provided by other sources of coverage that a daily newspaper has to choose from. But the effect of this equation on what a reader is presented with is significant.

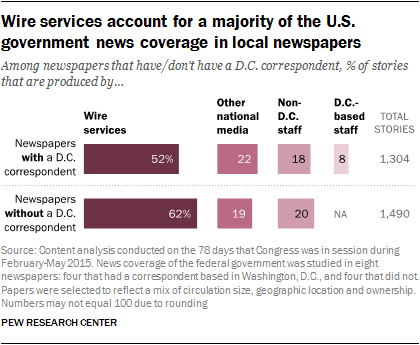

Across the four papers studied that support a D.C. reporter, readers received about six times as many stories from a wire service as from their Washington correspondent. In addition, they were presented with nearly three times as many stories by a national media outlet and around twice as many by other internal newspaper staff not based in D.C. In total, just 8% of national government coverage came from D.C. staff reporters, compared with half (52%) that came from wires and roughly a fifth each from other staff (18%) and from other media outlets (22%).

In total, these papers carried 1,304 federal government stories during the four months studied, of which Congress was in session for 78 days. This amounted to an average of 16.7 stories per day, with an average of slightly more than one story per day coming from D.C. correspondents.

The four papers without a D.C. reporter carried about the same amount of national government coverage overall (1,490 stories compared to 1,304), with stories from wire services largely accounting for the gap left unfilled by D.C.-based staff. About six-in-ten stories (62%) came from wires, while staff reporting and reporting from other media outlets each remained at about 20% of the total.4

D.C.-based correspondents keep a close eye on Congress, less so on local impact

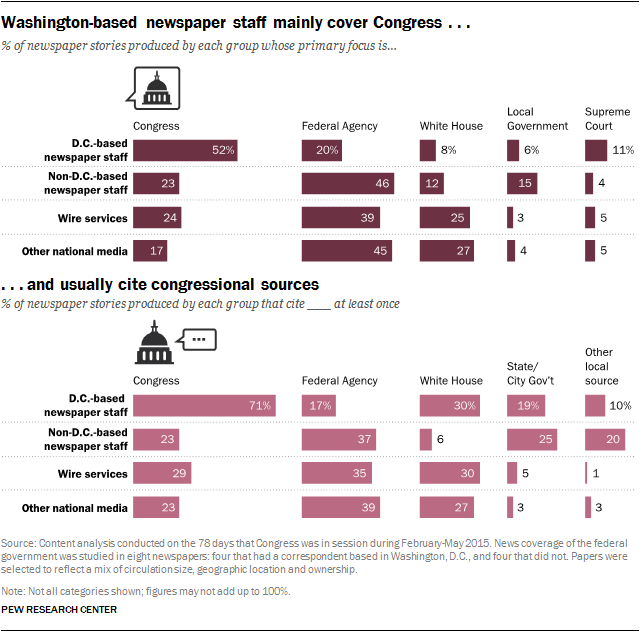

Even if the D.C.-based reporters account for a small slice of the national government reporting offered in their local daily newspaper, the coverage produced by D.C.-based staff reporters stands out in at least one major way: keeping close tabs on the work of Congress. The stories they produce tend to focus on Congress, often with quotes from one or more of the representatives that serve their readers’ home districts and states. Nearly three quarters (71%) of all stories written by a D.C. correspondent cited a member of Congress, and 28% included quotes from members of Congress on both sides of the political aisle.

Correspondents who were interviewed for this project clearly sensed a need for a high level of attention given to these lawmakers. Former Cox D.C. bureau chief and Washington Post ombudsman Andy Alexander described members of Congress as “the gateway to all these incredible decisions that are made in the bureaucracy that affect local communities.”

But following them takes effort. “A lot of these guys are getting a free pass here,” said Matt Laslo, a D.C. correspondent for public radio affiliates among other outlets since 2006. “And some of them just never do interviews,” opting instead to bypass journalists and communicate their messages directly with constituents.

The payoff for this kind of laser-focused attention by a correspondent has unique benefits for readers, said Todd Gillman, The Dallas Morning News D.C. bureau chief, who argues that without a correspondent in Washington, there is a great deal a reader would never know about a lawmaker’s “foibles” or what they might have said elsewhere, at another time, such as on the campaign trail. Not to mention the art of connecting dots over time with follow-up reporting: “Nobody else does that,” says Gillman.

This direct connection to members of Congress occurred far less frequently in stories produced by other staff. Just a quarter (23%) cited a member of Congress and only 4% offered the views of representatives from different political parties. Stories from wires, whose reporters are also often in D.C., were more equally divided across White House, congressional and other federal agency sources.

These D.C.-based reporters were also more likely than others to write about events having to do with Congress. Roughly half, 52%, of their coverage focused mostly on Congress. For example, one such reporter has, in addition to his regular coverage, a column called “D.C. Notes,” which usually summarizes several subjects being discussed in Congress. Just two-in-ten of stories by D.C.-based reporters, on the other hand, were about a federal agency such as the Department of Homeland Security or the State Department and about one-in-ten (8%) focused on the White House.

Federal agencies were a much larger portion of the coverage coming from the other three types of reporters – non-D.C. based staff (46%), wires (39%) and other national media outlets (45%). Wires and other national media outlets were also more likely to produce stories about the Obama administration (25% and 27% respectively) while staff reporters back home produced more stories about local governments’ response to federal activities (15% of all stories). An Associated Press story carried on the front page of one paper studied, for example, reported on the National Security Agency’s program to collect Americans’ phone records. Another AP story, carried the same day further inside the paper, discussed the Obama administration’s concerns about potentially reviving a rebel alliance in Syria.

The heavy focus on Congress often carries through to an inside-Washington lens

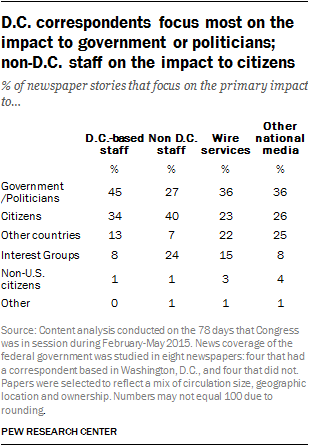

Another way of considering how the coverage from D.C.-based reporters might stand apart from other coverage about the U.S. government is by examining the approach taken by the reporter. Here, the data suggest that D.C.-based reporters, as they closely track the ins and outs of Congress, tend to present the news in a way that’s more likely to stay focused inward on Washington, rather than connecting the dots to the local communities that are served by the paper.

This comes through in two different ways. First, D.C.-based reporters are less likely than staff reporters back home to present their stories in a way that focuses mainly on how the news events might impact citizens. About a third (34%) of their coverage chiefly considered the news in terms of how it was likely to impact citizens, such as an article on how policy changes at the Department of Veterans Affairs would help veterans in a specific state. Instead, much of the coverage (40%) focuses on the impact to government and politicians – such as an article about elected leaders’ opposing views on a national piece of legislation, which focused mainly on how the stance could impact the electoral futures of these leaders. –Another 13% focused on the impact on U.S. relations with other countries.

This comes through in two different ways. First, D.C.-based reporters are less likely than staff reporters back home to present their stories in a way that focuses mainly on how the news events might impact citizens. About a third (34%) of their coverage chiefly considered the news in terms of how it was likely to impact citizens, such as an article on how policy changes at the Department of Veterans Affairs would help veterans in a specific state. Instead, much of the coverage (40%) focuses on the impact to government and politicians – such as an article about elected leaders’ opposing views on a national piece of legislation, which focused mainly on how the stance could impact the electoral futures of these leaders. –Another 13% focused on the impact on U.S. relations with other countries.

A number of reporters interviewed for this study spoke freely of the tendency to get drawn into an inside Washington mentality or to “get sucked into that bubble” as Laslo described it. MinnPost D.C. correspondent Sam Brodey described the tension of coexisting in two worlds: Washington Beltway culture and the community a thousand miles away whose readers he serves: “There are things that I’ll think are important that sometimes my editor has to check me and be like, ‘Man, nobody in Minnesota cares about that.’”

Among non-D.C.-based staff reporters, on the other hand, the greatest portion of stories, four-in-ten, focused mostly on the impact to citizens, while 27% mostly addressed the impact on government institutions. About another quarter (24%) focused on the impact to interest groups, such as the tech industry or telecom businesses.

Among non-D.C.-based staff reporters, on the other hand, the greatest portion of stories, four-in-ten, focused mostly on the impact to citizens, while 27% mostly addressed the impact on government institutions. About another quarter (24%) focused on the impact to interest groups, such as the tech industry or telecom businesses.

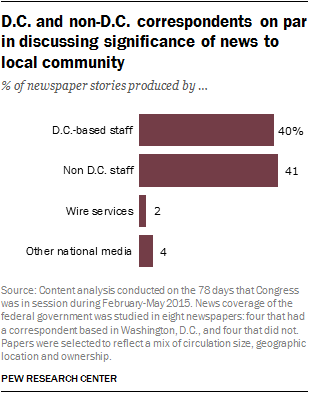

Stories from wire services and other national media were more evenly divided between addressing the impact on the government, citizens and U.S. relations with other countries. Researchers also measured whether a story mentioned in some way the significance of the news to the local area, whether aimed at community members, businesses or local government. Here, D.C.-based reporters were on par with their fellow staff based at home or somewhere other than Washington. Four-in-ten stories by D.C. correspondents (40%) mentioned in some way the significance of the news to the local area, as did 41% of stories from staff not stationed in D.C. One story about tax refund fraud, for example, mainly discussed how the IRS handles identity theft, but it also included a quote from the area’s U.S. Senator about how local residents might react to the news about the fraud and how they might be affected.

Both types of staff reporting are naturally more likely to mention the significance to the home area than wires and national media whose coverage is not designed for a local geographic audience.

Across all reporter types, very little enterprise reporting

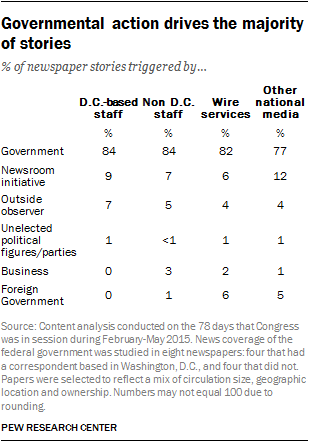

In the coverage studied, one similar characteristic across all four types of reporting groups is that the government, to a very large degree, is setting the news agenda. Whether written by D.C.-based staff of local newspapers, newspaper staff not in D.C., wire service reporters or those from other national media outlets, roughly eight-in-ten stories are triggered by something someone in the government said or did that journalists are then responding to such as a public statement or vote that occurred. In contrast, no more than one-in-eight stories came from a newsroom initiative to uncover or dig into a potential story. The national media stories that appear in these papers are somewhat more likely to be enterprise pieces (12%), but even so about three quarters (77%) are driven by the government.

In the coverage studied, one similar characteristic across all four types of reporting groups is that the government, to a very large degree, is setting the news agenda. Whether written by D.C.-based staff of local newspapers, newspaper staff not in D.C., wire service reporters or those from other national media outlets, roughly eight-in-ten stories are triggered by something someone in the government said or did that journalists are then responding to such as a public statement or vote that occurred. In contrast, no more than one-in-eight stories came from a newsroom initiative to uncover or dig into a potential story. The national media stories that appear in these papers are somewhat more likely to be enterprise pieces (12%), but even so about three quarters (77%) are driven by the government.

While reporting on daily government activity is an important part of keeping readers back home up to date, enterprise reporting often takes the time to uncover a story that would otherwise go unnoticed and could as a result trigger follow up activity.

A couple of examples of enterprise reporting during the four months studied included a front-page special report by a local reporter on hasty inspections and repairs following a military plane crash near a local airbase and a front-page piece by a national media outlet on how some U.S. spending in Iraq and Afghanistan has wound up financing the militants.

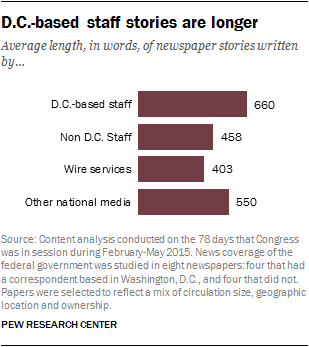

The D.C. staff-produced stories do tend to be longer than others, running for an average of 660 words compared with 550 for national media stories, 458 for other staff stories and 403 for wire stories. That may give room for somewhat more depth in the reporting or additional voices, but the data suggests the storyline itself remains largely driven by the events of the day.

The D.C. staff-produced stories do tend to be longer than others, running for an average of 660 words compared with 550 for national media stories, 458 for other staff stories and 403 for wire stories. That may give room for somewhat more depth in the reporting or additional voices, but the data suggests the storyline itself remains largely driven by the events of the day.

For some, this relatively low level of enterprise reporting is a shift from an earlier era of the press corps. One veteran correspondent, Miranda Spivack, described working for the Hartford Courant in an earlier era, when the paper once had four reporters staffing a Washington bureau. The reporting team would divide and conquer: “There was a point when I was there where I was [covering] Defense and also legal issues, [the] Supreme Court.” For Spivack, covering Defense meant examining defense spending in the legislation, which might have been written in by Sens. Chris Dodd or Joe Lieberman, and figuring out who or what in Connecticut would reap the benefits or suffer the consequences of spending decisions.