The story of who is covering federal government is a striking illustration of the shifting power dynamics within American journalism at large.

The story of who is covering federal government is a striking illustration of the shifting power dynamics within American journalism at large.

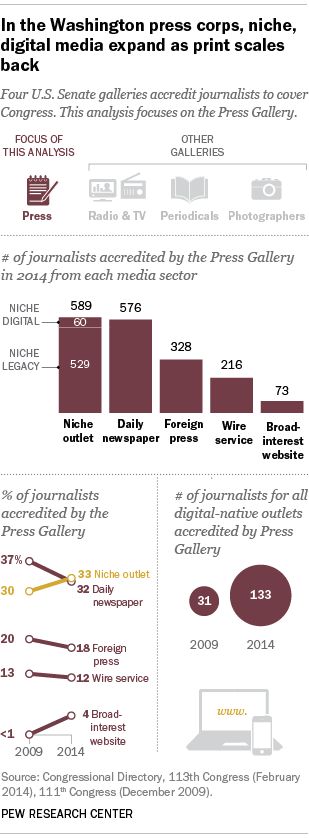

Reporters for niche outlets, some of which offer highly specialized information services at premium subscription rates, now fill more seats in the U.S. Senate Press Gallery than do daily newspaper reporters. As recently as the late 1990s, daily newspaper staff outnumbered such journalists by more than two-to-one.

Also increasing in number are reporters for digital news publishers – some of which focus on niche subjects, others on a broad range of general interest topics. In 2009, fewer than three dozen journalists working for digital-native outlets were accredited to the Press Gallery. By 2014, that number had risen to more than 130 – roughly a four-fold increase.

At the same time though, between 2009 and 2014, 19 local newspapers disappeared from the Press Gallery books, reducing the number of states with any local newspaper staff on the Hill from 33 to 29. Since those 2014 figures were tallied, other papers have turned out the lights in Washington, closing their bureau or simply electing not to replace an outgoing correspondent.

Some local papers have reestablished a presence in Washington – eight, between 2009 and 2014. And a handful of the digital start-ups with correspondents in Washington are locally-oriented. However, the rolls of the Regional Reporters Association – a group of Washington-based reporters that produce local and regional coverage – sit at 59 in 2015, down from around 200 in the mid-1990s.

For the American public, this translates to more digital options for coverage at the national level as well as options for those who have access to trade publications and specialized information products, but also a continuous chipping away at the number of reporters on the Hill covering the federal government on behalf of local communities.

What do these changes mean for the news delivered to readers back home? Do residents served by newspapers with correspondents in D.C. receive a different level of reporting about the activities of federal government and how they relate to local life than those without?

In an attempt to shed light on this question, Pew Research Center systematically studied coverage of the federal government in eight local newspapers from across the U.S., four with a D.C. reporter and four without, over a period of four months. The goal was to use this snapshot of reporting on Washington to get a sense of the ways that coverage from Washington-based correspondents might differ from coverage coming from newspaper staff not stationed in D.C., wire services or other national media. Among the other dimensions studied were how often correspondents cover Congress, use a Congressional source in their stories, frame the impact of the news they cover around citizens, or make a local connection between events in the capital and the communities served by the papers themselves. This report was made possible by The Pew Charitable Trusts, which received support for this study from The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation.

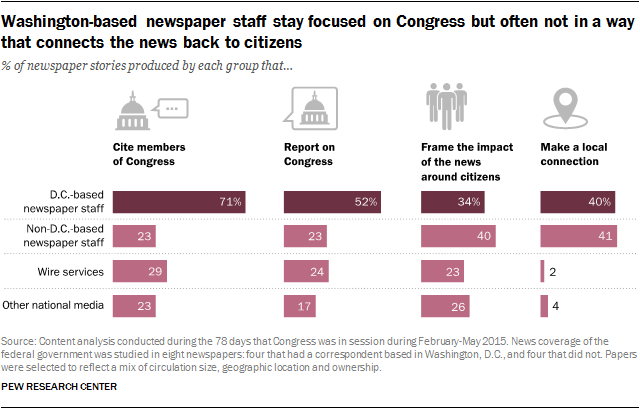

The findings of this content analysis reveal that coverage by D.C.-based reporters stays more closely tethered to the institution and work of Congress than other reporting in the papers studied, usually with direct quotes from members of Congress. But there are also signs that these reporters are often Beltway-focused, with a tendency to keep the emphasis of the stories aimed at the government and in a way that does not tie the significance of the news back to the local community. But perhaps of more importance to the reader overall is that of all the coverage about federal government appearing in these papers, the portion that comes from D.C. based-reporters accounts for less than 10%. Instead, the greatest portion of federal government coverage by far comes from wire service stories.

From February through May of 2015, the period for which these newspapers were studied, about seven-in-ten stories produced by D.C. correspondents (71%) contained a quote from a member of Congress. That is three times the rate of other newspaper staff reporters who were not based in D.C. Further, about three-in-ten stories (28%) from D.C.-based staff cited national politicians on both sides of the political aisle, seven times that of stories from their colleagues outside the beltway.

At the same time, though, nearly half (45%) of stories from these D.C.-based correspondents were written in a way that mainly addressed the impact on the government or individual politicians, such as a story about Obama’s request for U.S. troops to combat ISIS, which focused mainly on relations between the president and Congress. Only about a third (34%) of stories focused mainly around the impact on citizens.

At the same time, though, nearly half (45%) of stories from these D.C.-based correspondents were written in a way that mainly addressed the impact on the government or individual politicians, such as a story about Obama’s request for U.S. troops to combat ISIS, which focused mainly on relations between the president and Congress. Only about a third (34%) of stories focused mainly around the impact on citizens.

In comparison, reporting by non-D.C. based staff, such as those covering Washington activities from home, was more likely to discuss the impact on citizens (40%) and less likely to focus on government or politicians (27%).

The two cohorts of staff reporters studied in this analysis were roughly equal in the portion of coverage that somehow makes a connection to the local community, whether to local businesses, government entities or residents, at about 40% each. That suggests then, that D.C. based staff are about as likely as non-D.C. staff to find a local lens to the news but are less likely to tie it directly to what it means for citizens.

To be sure, local connections are nearly absent from the stories produced by wire services and other national media, which are themselves not connected to the local area in any way. Coverage from these sources was also somewhat less likely than other coverage to focus on the impact to citizens, instead offering a wider mix of the impact on citizens, the U.S. government and countries outside the U.S.

In addition, news events themselves will not always make for a direct opportunity to explore the citizen angle. There are certainly situations where the impact of news on some other actor or institution besides the public is a critical component. Yet, at least among some correspondents, there is a sense of duty to make Washington relevant to citizens. “If Washington already seems remote, certainly regional reporters can play a role in making it a little closer, a little more understandable,” said James R. Carroll, former Washington bureau chief for The Louisville Courier-Journal.

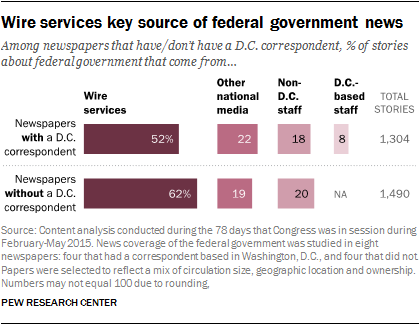

When looking at how these different types of reporting add up in sheer volume for readers, wire stories carry the weight, both in the papers with and without D.C. correspondents. Fully 52% of the federal government stories produced by papers supporting a D.C. correspondent came from wire services – more than six times that of the 8% of coverage coming from D.C reporters. Stories from D.C. reporters were also less than half as prevalent as stories produced by other staff writers (18%) or other news outlets (22%). Papers without a D.C. reporter produced about the same amount of coverage, with wire services playing an even more critical role – providing 62% of all coverage about the federal government.

Some of this may speak to the practical limitations of what any one correspondent can do, as many newspapers with any kind of Washington presence today get by with just one correspondent. Indeed, stories from wire services often provide insights into international affairs or the activities of other federal agencies.

And there is some evidence of additional impact that a newspaper with its own D.C. correspondent may have beyond just the raw number of stories produced by that designated staff. Articles produced by D.C. correspondents are more likely than others to be placed on Page One, appearing in front of even casual readers, and they also tend to be longer. And these papers are more likely to publish stories by other staff with D.C. bylines.

In assessing the influence of these dwindling D.C.-based newspaper correspondents, it is clear that they keep a close and consistent eye on Congress. And it may be that the most important results of their labor are also the most difficult to quantify: the potential influence they may wield through the mere fact that a Senator knows his or her actions are being reported back to voters, the deep institutional knowledge a correspondent accrues over time, and the relationships a correspondent may form with those who pull the power levers. Sometimes, the impact comes from simply being in plain sight. The question is whether in trying to do more with fewer resources in an increasingly fast-paced news environment, while at the same time trying not to “get sucked into [the Washington] bubble,” as D.C. correspondent Matt Laslo puts it, what they are able to deliver to readers back home accomplishes the difficult work of connecting communities to their federal government.

This analysis builds from a study produced by Pew Research Center in 2009, which examined the makeup of the Washington press corps from 1985 through 2009, chronicling the rise of niche and foreign press, as well as the decline of legacy media in Washington over the course of several decades. This study examines the changes in that makeup since 2009 and adds a study of coverage in newspapers with and without a D.C.-based correspondent. More details about the methodology are provided here.

Terms associated with the accounting of journalists who make up the Washington press corps:

“Washington press corps” refers to the group of journalists based in Washington, D.C., covering the federal government.

“Niche outlets” are news organizations that offer specialized coverage of a specific topic or group of closely related topics.

“Broad-interest websites” offer a wide range of news, from politics to sports, for a general audience.

“Digital-native” news outlets are those whose first place of publication was on the web, as opposed to legacy media organizations that developed a web presence after the consumer internet became available. Digital-native news outlets can be either broad-interest, such as The Huffington Post, or niche, such as Kaiser Health News.

The “Congressional Directory,” made available during the first session of each new Congress, is the official directory of the U.S. Congress. Included in the directory are the lists of the journalists accredited to the Press, Radio and Television, and Photographers’ galleries, defined below.

- The “U.S. Senate Press Gallery” accredits individual journalists who represent daily newspapers, wire services or online publications to cover the U.S. Congress. These journalists are granted access to the gallery and the rest of the Capitol complex.

- The “U.S. Senate Periodical Press Gallery” accredits journalists who represent magazines, newsletters, non-daily newspapers and some online publications to cover the U.S. Congress. Throughout the report, this group is referred to as the Periodical Gallery.

- The “U.S. Senate Radio & Television Correspondents Gallery” accredits journalists and other news personnel who represent television and radio outlets to cover the U.S. Congress. Throughout the report, this group is referred to as the Radio and Television Gallery.

- The “U.S. Senate Press Photographers’ Gallery” accredits press photographers working for newspapers, news magazines, wire services and photo agencies to cover the U.S. Congress. Throughout the report, this group is referred to as the Photographers Gallery.

Terms associated with the analysis of federal government news coverage in eight newspapers:

“D.C.-based staff reporters” are journalists who work for one of the newspaper studied and are stationed in Washington D.C.

“Other national media” denotes a national news organization whose coverage appears in one of the local papers studied, such as The New York Times or The Washington Post. Wire services are counted separately.

“Primary impact” is a concept used in the analysis of newspaper content to identify instances where the action that is the focus of the story is directly linked, by the author, to some group or institution. For instance, a story where the primary impact is “citizens” would explore how citizens’ circumstances will somehow be changed by new legislation in Congress.