Much of this study has focused on the efforts of D.C. correspondents in covering the federal government for local communities situated outside of Washington. But, with the vast amount of news coming out of Washington day in and day out, it is wire services that supply the majority of this news to local newspaper readers, even if the paper has a reporter stationed in the nation’s capital.

The eight newspapers in this study offered their readers 1,595 stories from wire services – nearly six-in-ten of all stories about national government produced over this four-month period. While in many cases the same stories – or close versions of them – were carried in multiple newspapers, for any individual reader this amounts to more than half of the national government coverage they receive: 52% for readers of papers with a D.C.-based correspondent and 62% for readers of papers without. The majority, though not all, of the wire content comes from The Associated Press – an organization which, according to the most recent data from the Senate Press Gallery, accounted for 121 of the 1,782 reporters accredited to cover Congress.

The eight newspapers in this study offered their readers 1,595 stories from wire services – nearly six-in-ten of all stories about national government produced over this four-month period. While in many cases the same stories – or close versions of them – were carried in multiple newspapers, for any individual reader this amounts to more than half of the national government coverage they receive: 52% for readers of papers with a D.C.-based correspondent and 62% for readers of papers without. The majority, though not all, of the wire content comes from The Associated Press – an organization which, according to the most recent data from the Senate Press Gallery, accounted for 121 of the 1,782 reporters accredited to cover Congress.

It is important to note that the data here represent what newspaper editors chose to carry in the papers, not all that the reporters for the wire services produced. In making those choices, editors seem to see a clear role for the wires – one distinct in many ways from what is provided by staff reporters either in D.C. or out. The stories are more national and international in scope, are tied more to coverage of the administration and federal agencies than of Congress, and include more focus on how the news will impact other countries than do staff-produced articles. What they do less of, as could be expected, is connect back to the local communities that these papers serve.

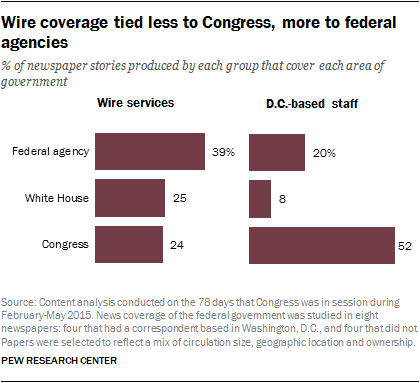

The wire stories that appeared in these eight papers focused on a range of government areas, including Congress, federal agencies and the White House. But they focused more heavily on federal agencies and the White House than on Congress, leaving the bulk of congressional reporting to the paper’s own staff. About four-in-ten wire stories (39%) covered federal agencies, while another quarter each was devoted to the Obama administration (25%) and to Congress (24%). By contrast, just 20% of D.C. correspondents’ stories related to activity tied to federal agencies and 8% to the Obama administration, while about half (52%) were tied to Congress. (Other national media, like the wire copy, tended to focus on federal agencies and the White House.)

The wire stories that appeared in these eight papers focused on a range of government areas, including Congress, federal agencies and the White House. But they focused more heavily on federal agencies and the White House than on Congress, leaving the bulk of congressional reporting to the paper’s own staff. About four-in-ten wire stories (39%) covered federal agencies, while another quarter each was devoted to the Obama administration (25%) and to Congress (24%). By contrast, just 20% of D.C. correspondents’ stories related to activity tied to federal agencies and 8% to the Obama administration, while about half (52%) were tied to Congress. (Other national media, like the wire copy, tended to focus on federal agencies and the White House.)

Coverage from wire services also stands out from that of D.C. and non-D.C. staff when it comes to whom or what is primarily impacted by national government events. Overall, wire coverage was generally more evenly distributed, falling in between the amount of coverage by both Washington-based and non-Washington based reporters in both of these cases. The one area of impact it was more likely to focus on was that of other countries and it was least likely to focus on how events in Washington would impact citizens: About a quarter of wire stories were dedicated to each.

Along those lines, just 2% of wire stories made any reference to the impact upon the local community (and when they did, it was mostly because they had quoted an elected leader from the area), compared with 40% of stories by staff reporters, both in and out of D.C.

Overall, the data suggest that, while the job of tying stories back to local readership is almost solely done by staff reporters, wire coverage, while heavily national in scope, tended to be less focused on one area of government or one way of presenting government developments than the coverage by other kinds of reporters. This may add some broader insight into how newspapers are dedicating the limited staff resources they have. In a time when resources for newspapers continue to be tight and newspapers’ reporting presence in Washington continues to diminish, the decisions around wire coverage play a large role in the nature of the national government reporting readers receive.