In possibly the first survey of its kind, in 1983, polling firm Louis Harris & Associates asked U.S. adults if they had a personal computer at home and, if so, if they used it to transmit information over telephone lines.2 Just 10% of adults said they had a home computer and, of those, 14% said they used a modem to send and receive information. The resulting estimate was that 1.4% of U.S. adults used the internet.

Personal computer owners were then asked, “Would your being able to send and receive messages from other people…on your own home computer be very useful to you personally?” Some 23% of the computer owners said it would be very useful, 31% said it would be somewhat useful, and 45% of those early computer users said it would not be very useful. And 74% of computer owners agreed with the statement, “The trouble with purchasing and bill-paying by computer is that it will be too easy to buy too many things that aren’t in the family budget.”

Looking back, this should come as no surprise. A blinking cursor on a blank screen was not exactly an invitation to dream, at least by most people’s estimates. The internet would remain a clunky, text-based resource for another six years.

In 1989, Tim Berners-Lee changed all that by introducing the concept of a “distributed hypertext system,” which could link files in an ever-expanding network shaped more like a cobweb than like a chain or tree structure, as was standard at the time. The World Wide Web was born.

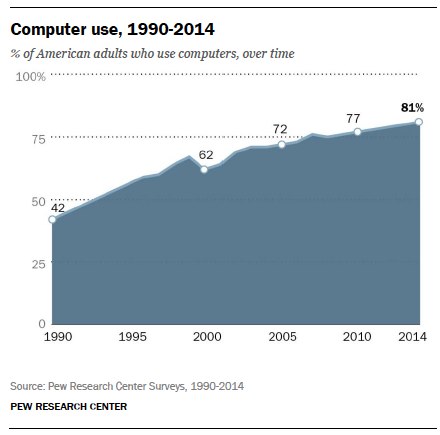

Within a year, the Pew Research Center fielded its first question about computer use in a national survey. In February 1990, 42% of U.S. adults said they used a personal computer, even if only rarely. Men and women were about equally as likely to use computers, as were whites and blacks. College graduates were the most likely group to say they use computers on a regular basis: 46%, compared with 16% of those who had completed high school.

But counting the number of computer users was not going to cut it among people who took the internet’s potential seriously.

In 1994, Donna Hoffman and Thomas Novak, professors at the Owen Graduate School of Management at Vanderbilt University, wrote, “Current approaches to estimating the number of users of the internet are akin to estimating the number of people in the U.S. by sampling the number of buildings, without regard to their function or contents. We propose a completely different way—rather than inferring the number of users by counting and sampling machines, sample the users themselves.”3

The computer connection

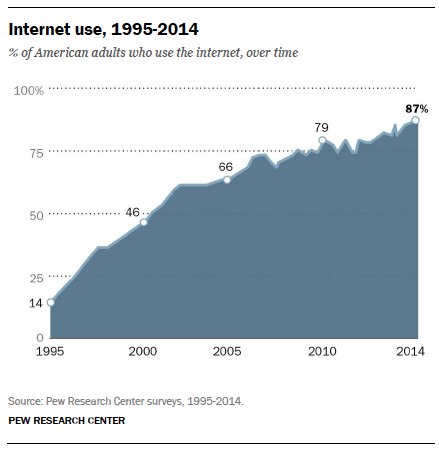

In 1995, the Pew Research Center did just that, finding 14% of U.S. adults with internet access.4 Most were using slow, dial-up modem connections—just 2% of internet users were comparatively screaming along with an expensive 28.8 modem.

To put things into further perspective, 42% of U.S. adults had never heard of the internet and an additional 21% were vague on the concept—they knew it had something to do with computers and that was about it. Yet even then, 63% of people who used a computer at home said they would miss it “a lot” if they no longer had one.

Early researchers were not too far off the mark, however, focusing on computer penetration into American households, schools, and businesses. Twenty-five years ago, anyone who wanted to use the internet needed to have access to a computer. Again, in 1990, 42% of U.S. adults said they used a computer at their workplace, at school, at home, or anywhere else, even if only occasionally.

Now, eight in ten U.S. adults (81%) say they use laptop and desktop computers somewhere in their lives—at home, work, school, or someplace else.

Education has always been a significant factor when it comes to predicting someone’s likelihood to use a computer. In both the 1990 and the current sample, there is about a 30 percentage point gap in computer use between adults with a college degree and adults with a high school diploma. Age is also a durable predictor for computer use: 56% of adults ages 65 and older now say they use a computer, compared with 89% of 18-29 year olds, for example.

Cell phones and mobile connectivity

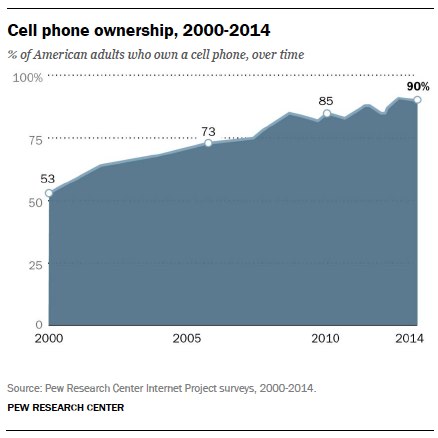

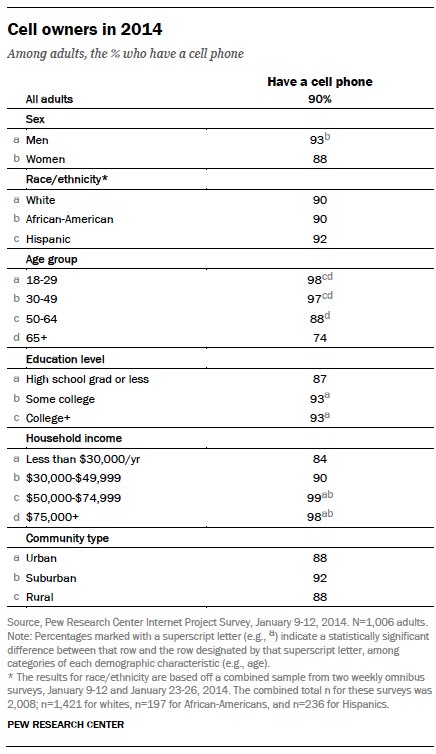

Nowadays, desktop or laptop computer access is no longer a prerequisite for internet access. Ninety percent of U.S. adults have a cell phone and two-thirds of those say they use their phones to go online. One third of cell phone owners say that their primary internet access point is their phone, not some other device such as a desktop or laptop computer.

The Pew Research Center’s earliest measure of cell phone ownership was in 2000, when 53% of U.S. adults said they had a cell phone.

Education is less of a factor in predicting cell phone ownership than in predicting computer use: 93% of adults with a college degree have a cell phone, compared with 87% of adults with a high school education or less. Age, however, is a factor: 98% of 18-29 year-olds say they have a cell phone, compared with 74% of adults ages 65 and older.

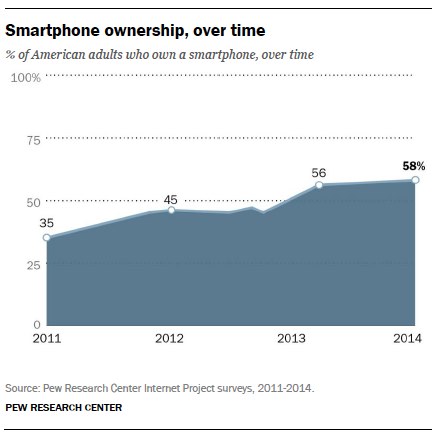

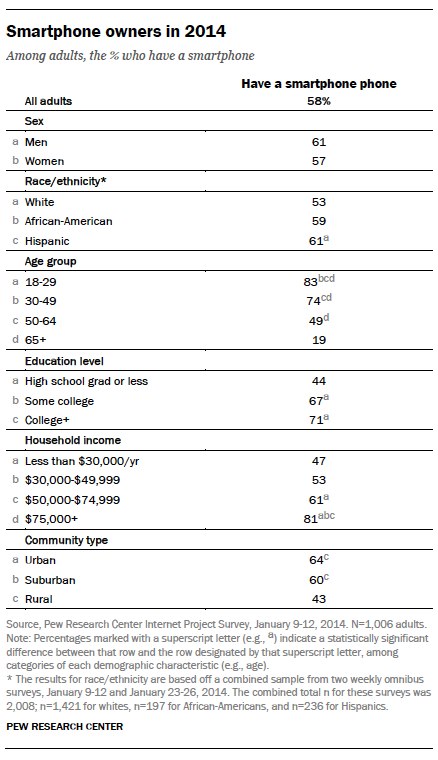

Mobile access to the internet took a huge leap forward when smartphones were introduced in mid-2007 with the introduction of the iPhone. Now, 58% of U.S. adults say they have a smartphone. Higher education is associated with smartphone use, as is being younger than age 50.

Internet adoption over time

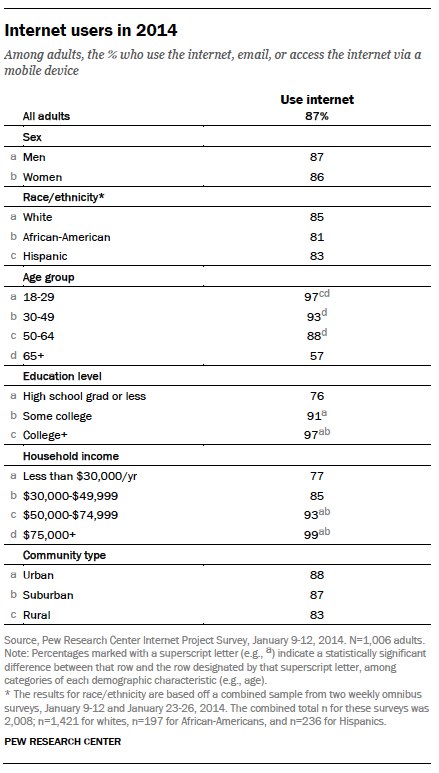

Adding all of these access points together, 87% of U.S. adults say they use the internet, at least occasionally—the highest percentage captured in a Pew Research Center poll since we began measuring it in 1995, when just 14% of U.S. adults had access.

The latest findings illustrate remarkable growth in internet adoption across all demographic groups. Yet, there still are notable differences in adoption: Those ages 65 and older are considerably less likely to use the internet than younger Americans; those with college degrees are more likely than those with high school diplomas or no high school diploma to be online; and those in higher-income households are more likely to be online than less well-off Americans. More Pew Research material on digital differences can be found here.

Another way to look at the increasing importance of the internet is to look at the frequency with which people go online. Seventy-one percent of all American adults say they use the internet on a typical day. This is a significant increase from the year 2000, our first measure, when just 29% all adults said they went online on a typical day.

The vast majority of internet users go online from home on a typical day—90% say that, up from 76% in 2000. The percentage of internet users who go online from work has not changed as much in the past 15 years: 44% of internet users say they go online from work on a typical day in 2014, compared with 41% of internet users who said that in 2000.

The rise of mobile device use represents the biggest shift in access over the past ten years: 68% of U.S. adults now say they access the internet on a cell phone, tablet, or other mobile device, at least occasionally.

All of this data covers the mechanics of the internet’s spread— the how of access—but it doesn’t address why people flocked online.

Is it because they could access a seemingly limitless amount of information? Is it because they could communicate, in real time, with friends and family across the globe? Is it because they could share their deep expertise in a subject? Is it because they really liked that cute boy and wanted to know if he is single? Like the parable of the blind men describing an elephant—one feels the leg and says it is like a pillar, another feels the tail and says it is like a rope—people’s experiences of the internet are highly subjective. Instead of guessing at why people were drawn to it, or were required to start using it, we asked people to assess the role of the internet in their lives more generally.