Introduction

The internet’s role in campaigns has grown dramatically in the past decade. Several forces are driving this.

At the top of the list is the growth of broadband. There were only a handful of home broadband users in 1996. When the Pew Internet Project began asking questions about broadband access in the summer of 2000 only 3% of Americans had high-speed connections at home. In the post-election survey reported here fully 43% of American adults have broadband connections at home. Those always-on linkages and faster delivery make it easier for people to get news online.

Second on the list is the increase in number of internet users with veteran status. At the dawn of the Pew Internet Project’s work 46% of Americans were internet users and just 30% of them had three or more years of experience. In August, a Project survey found that 70% of Americans use the internet and fully 66% of have six or more years of experience. The more years people are online, the more likely they are to do more things online, including getting their news. Indeed, many users are now sophisticated enough to begin customizing their online news experience and regularly check their favorite news sites for headlines or more in-depth information on the stories about which they are aware. In a December 2005 survey, the Project found that 19% of internet users had customized a news site or set up a news alert to deliver the information that particularly interested them.

Third is the growth of news content online. News is a primary information “currency” online. Many thousands of Web sites now offer news and headline services, even sites that are not run by news organizations.

Fourth is people’s increased fluency with web communication tools. Online communication applications have become so embedded in Americans’ daily rhythms that it is natural people will use email and instant messaging and now even cell phone text messaging as ways to discuss politics, share jokes about candidates, or forward the latest insider political information to friends. At the same time, campaigns are encouraging greater internet use by increasingly relying on email and Web site alerts to stay in touch with voters.

There were other factors in 2006 that might account for higher internet use. It was a very exciting campaign season with much at stake; a great deal of the mainstream media coverage in the late stages of the campaign focused on the prospect that Democrats might seize one or both congressional chambers. The prospect of a shift in power might have drawn more people to all kinds of news consumption, including heavier user of online resources.

With all that as background, this section of the report will cover the new contours of the online political landscape.

Television still wins the political news horserace – by a wide margin.

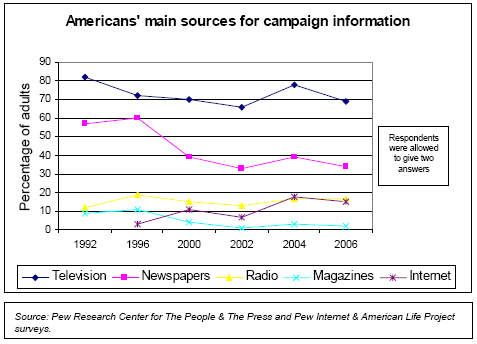

As it has been for generations, television remains ahead of other media in 2006 as a news source. On any given day when this survey was in the field in November, 61% of all Americans say they watched a television news program, 38% read a daily paper, and 21% got news of any kind online.

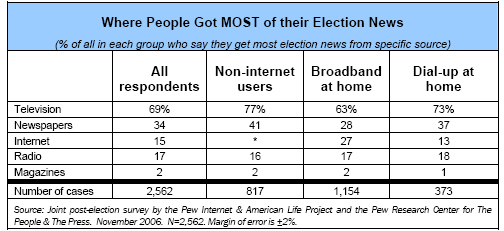

When it comes the political news, television’s lead over other media is even more pronounced. Fully 69% of all Americans said they went to the television for most of their news about the campaign – twice the proportion of those who cited newspapers (34%), four times the proportion who singled out radio (17%) and the internet (15%).

Even for internet users (not the public as a whole), television and newspapers outpace the internet as a campaign source. Among America’s 136 million adult internet users 66% say television was their main source of political news in 2006 and another 31% cite newspapers. That compares with the 22% of internet users who cite the internet itself as their main source of campaign news.

Still, television’s lead is slipping and the only notable growth in any political news channel since 1996 has been on the internet. And the most dramatic shift to reliance on the internet has come among those with broadband connections at home.

15% of all Americans say the internet was their main source of political news and information in the 2006 campaign – up from 7% who said this in the last mid-term election in 2002.

The proportion of Americans who say the internet was a main source of campaign news and information for them grew fivefold since 1996 and doubled since the last mid-term election in 2002. Some 15% of all Americans – and 22% of internet users – say the internet was the place where they were getting most of their news about the 2006 races. Significantly, for an off-year election, the proportion of Americans relying on the internet this year was close to the 18% of Americans who relied on the internet during the hotly-contested presidential election in 2004.

Among other things this means that the internet now rivals radio as a principal source of political news for all Americans.

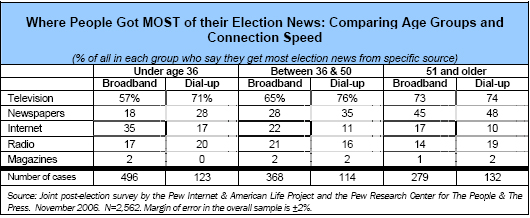

For some groups the internet has become a more important source than some traditional news channels. For instance, home broadband users are just as likely to count on the internet as they are for newspapers to get political news. And home broadband users are notably more likely to rely on the internet than on the radio.

For young broadband users (those under age 36) the media use story is even more dramatic. Among them, there is a striking 2-1 lead for the internet over newspapers as a main source for campaign news. For these highly-engaged and wired Americans, use of internet has a replacement effect on other media. In other words, the internet pushes out newspapers and to a lesser extent TV. For older broadband users, the internet plays a supplementary role and doesn’t push out (very much, at least) newspapers or TV as news sources.8

Comparative analysis of the 2006 post-election survey and our 2002 post-election survey illuminates to some extent the sources of the increase in reliance on the internet. Growth in broadband adoption had something to do with it; we estimate that higher levels of home high-speed adoption accounts for roughly 30% of the greater reliance on the internet for most campaign news over the 2002 to 2006 timeframe. In other words, the share of people turning to the internet as a main source of mid-term political news doubled in four years and about a third of that growth is due to growth in home broadband adoption.9

Where does the rest of the growth come from? There isn’t an entirely clear story here but it is reasonable to speculate that growth in online experience may be part of the answer, as well as improvements and innovations related to the political information that is made available online. Finally, to the extent that people use the internet to dig deeper into news stories of interest to them, greater interest in the 2006 mid-term election relative to 2002 might be behind some of the growth in reliance on the internet for campaign news.

31% of Americans – more than 60 million people – used the internet for political purposes in campaign 2006.

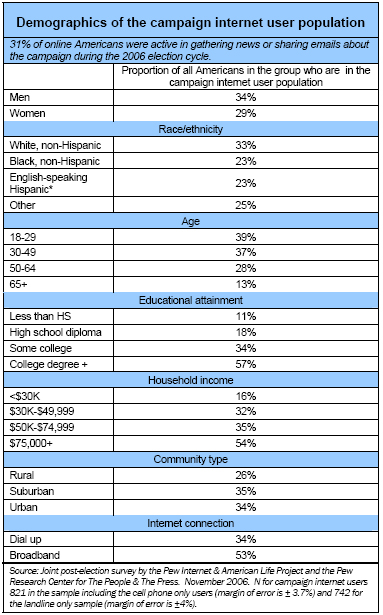

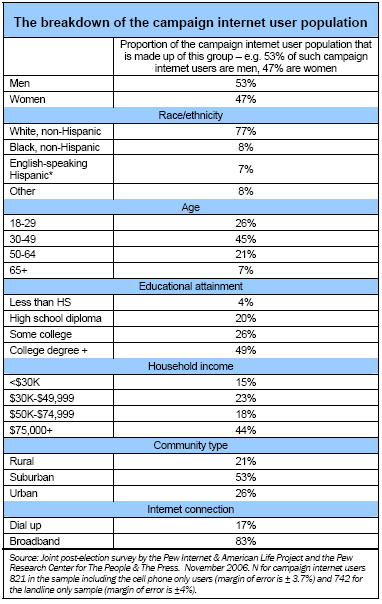

We calculate the overall campaign internet user population by asking several questions about getting news and information on the internet and using email to discuss politics. In all, we calculate that 46% of internet users – or 31% of the entire adult population – used the internet for some kind of political purpose during the last election.

We used different questions to identify this population this year than were used in previous campaigns so it is not possible to do precise comparisons of this group to online politics consumers in previous elections. But is clear that this group is more diverse than the original online political junkies of 1996. Surveys by the Pew Research Center for The People & The Press at the time found the online political class was two-thirds male, disproportionately young, very likely to hold college or graduate degrees, and heavily populated with suburban dwellers.

In 2006 the demographic composition of the group is more like the general population of the country, though it is still not a completely equivalent group. It is still disproportionately composed of those with college degrees and who live in households earning over $75,000.

Among other things, this shift in population composition made the online political news consumer population a bit less intense as a group about political news, more likely to cite convenience as a primary reason to get political news online and more likely to visit the sites of traditional news organizations.

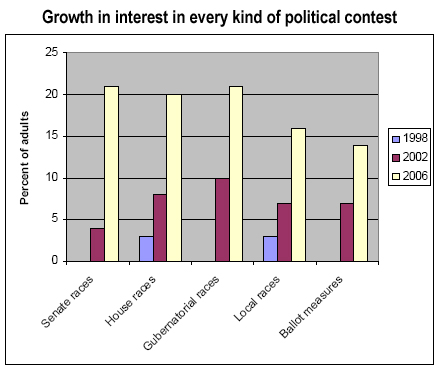

Campaign internet users cared most about Senate and House races, but interest in all kinds of races has risen since 2002.

The increase in the number of people who use the internet for political purposes is reflected in the number of those getting online news and information about particular kinds of races. The number of Americans getting information about Senate races rose fivefold since 2002, and at least doubled in the case of House races, local contests and gubernatorial campaigns.

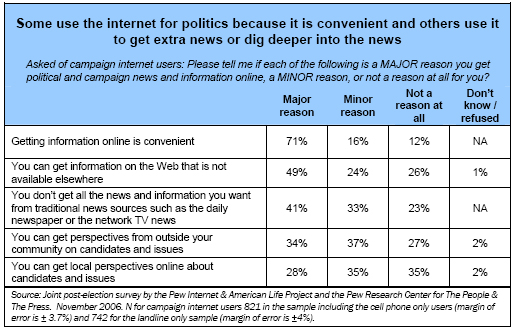

Campaign internet users cite convenience as the primary factor for their reliance on the internet. However, nearly two-thirds of campaign internet users say they like online news resources because they provide more material than they get from other news media.

For most of those interested in political content and chatter about the campaign, the ease of using the internet was the most compelling reason to use the internet for politics. Fully 71% of campaign internet users cite convenience as a major reason they use the internet for political activities.

At the same time, nearly two-thirds of campaign internet users cite unique features of internet news as a major reason for getting political information online. Some 49% say they appreciated that they get information on the Web that is not available elsewhere and 41% say a major appeal of the internet was that they could not get all the political information they wanted from traditional news sources. Altogether, 65% of campaign internet users cite at least one of those as a major reason.

In addition, we asked new questions this year about other factors that might be driving voter interest in getting political news and information and they further confirm the notion that for some users the internet is force that helps them connect to the world outside their community while others say it connects them more directly to their locale. Some commentators have called this “glocalization” and it shows up in our survey this way: A third of campaign internet users (34%) say a major reason to get news online was to get perspectives from outside their communities and 28% say getting local perspectives was a major reason. A significant number (22% of campaign internet users) cite both reasons for their use of the internet.

Mainstream news sources dominated the online news and information gathering by campaign internet users. At the same time, blogs, comedy sites, government websites, candidate sites, and alternative news sites were a part of the information mix for many.

Asked where they went online to get news and information about the campaign, the greatest number of campaign internet users cite traditional news organizations or online services that syndicate news from traditional sources, such as wire services. However, more than half of campaign internet users (53%) go to Web sources beyond those that are fed by traditional news media in the United States – that is, they got political news from sites such as alternative news sites, international news sites, blogs, comedy sites, local and state government sites, candidate sites, and email listservs.

Here is how the Web traffic broke down for the 31% of Americans (more than 60 million) who are in the campaign internet user population:

- 60% got news and information about the campaign from news portals such as Google News or Yahoo! News This is the first post-election survey in which we have framed the question this way and it is striking to note that these services were especially popular with younger internet users (those age 18-29 years old) overall and even more so with civically-engaged young users, particularly those who follow political news closely.

- 60% got news and information about the campaign from TV network websites such as CNN.com or ABCNews.com. These kinds of sites were particularly compelling to campaign internet users between ages 30-49 and those who have broadband connections at work, presumably because a portion of campaign internet users were checking in with their favorite sites during the day on the job.

- 48% got news and information about the campaign from local news organization websites. Again, these kinds of traditional news organization websites were particularly appealing to those age 30-49 years old. These sites were also especially important to those who say they liked the internet because it gave them news and information with local perspective.

- 31% got news and information about the campaign from websites of major national newspapers such as USA Today or the New York Times. These sites are especially popular with those who have higher levels of education and with those who have broadband connections at work. These sites were also especially important to those who say the internet gave them access to non-local perspectives on politics.

- 28% got news and information about the campaign from the websites of state or local governments. There were no notable demographic traits that characterized the campaign internet users of these sites. They were evenly spread among all ages, races, and socio-economic classes. However, these sites had special appeal to campaign internet users who go online in hopes of getting extra local perspective on politics.

- 24% got news and information about the campaign from issue-oriented websites. Internet users with relatively high levels of education were drawn to these sites. These sites particularly appealed to women in the campaign internet user population. They also were attractive to those who do not feel that traditional news sources like television and newspapers give them all the information they seek and to those who are looking for perspective from non-local sources.

- 20% got news and information about the campaign from blogs. Those with relatively high levels of education and high levels of household income were particularly drawn to blogs as were campaign internet users in their 30s and their 50s. Blogs held special force with those who used the internet to get political news and information from places outside their communities.

- 20% got news and information about the campaign from international news organization websites, such as the BBC or Al Jazeera. Online men were more likely than women to be drawn to such sites, as were younger campaign internet users. They also were a favorite destination of people who wanted perspective from outside their community and also those who felt the internet gives them information beyond what is available from traditional news sources.

- 20% got news and information about the campaign from websites created by candidates. These sites were disproportionately used by civically-engaged young voters and voters who felt that the internet is a good source of information that is unavailable elsewhere. They were also important to people who see the internet as a place to get local perspectives.

- 19% got news and information about the campaign from news satire websites like The Onion or The Daily Show. These sites drew a lot of traffic from younger users (those under age 30). Some 30% of campaign internet users under age 30 went to such sites. Further, these sites were appealing to those who felt the internet gives them political information that is not available elsewhere.

- 19% got news and information about the campaign from the websites of radio news organizations, such as National Public Radio. Such sites are particularly appealing to those with higher levels of education.

- 10% got news and information about the campaign from websites of alternative news organizations, such as Alternet.org or NewsMax.com. Not surprisingly, these sites were especially popular to those who liked the internet for giving them information not available in traditional news sources like television and newspapers.

- 10% got news and information about the campaign from email listservs. Interesting, listservs were seen as a good source of political information from places outside a person’s local community.

We recast many of these questions from previous surveys so in those cases it is not possible to do detailed election-to-election comparisons. Still, there is notable growth in some of the general categories between the two elections. For instance: The percent of all Americans who used the websites of local news organizations in 2002 was 4% and this year amounted to 11% of the entire population; the percent of the entire population using issue-oriented websites in 2002 was 2% and in this cycle was 8%; the percent of the full population using candidate sites in 2002 was 2%, compared with 6% this election.

Campaign internet users took advantage of online political resources in many ways, but most commonly checked candidates’ positions on the issues.

The internet has made it easy for citizens to engage in politics online. Here is a rundown of some of the activities that they performed:

- 52% of campaign internet users looked for information about candidates’ positions on the issues or voting records – that amounts to 20% of all Americans who used the internet this way.

- 41% of campaign internet users checked online about the accuracy of claims made by or about the candidates – that amounts to 14% of all Americans who used the internet this way.

- 32% of campaign internet users watched video clips about the candidates or the election online – that amounts to 13% of all Americans who used the internet this way.

- 27% of campaign internet users searched online for candidate endorsements or ratings by outside organizations – that amounts to 9% of all Americans who used the internet this way.

- 9% of campaign internet users signed up to receive emails from candidates or campaigns – that amounts to 3% of all Americans who used the internet this way.

- 5% of campaign internet users contributed money to a candidate – that comes to 3% of all Americans who gave money online to a candidate.

For all of these items, several demographic and technological realities stand out. Those doing these activities are significantly more likely than others to have a broadband connection at home, a college education, live in a household with relatively high income, and be under age 40.

In addition, online men and more likely than women to check on claims about and endorsements of candidates, and watch videos.

A new class of online political activist is emerging online; 23% of campaign internet users are in this new political elite.

The campaign of 2006 marked an important breakthrough moment for online video and politics – especially citizen-created or shared video. Virginia Sen. George Allen’s campaign went into a tailspin after he addressed a videographer from rival James Webb’s campaign as “Macaca,” a term some considered derogatory and racist. Similarly, video of Montana Sen. Conrad Burns dozing off during Senate business was viewed and widely debated by his constituents. And Rep. Sue Kelly of New York was captured on video fleeing reporters rather than answer their questions about her views on Mark Foley’s activities with congressional pages. All three lost their races.

Some 21% of campaign internet users (or 13% of the entire adult population) viewed videos online about the campaign. That is the same proportion of Americans who viewed online video in the 2004 presidential election race and is an illustration of how Americans who have brought broadband connections into their homes have added to their political information resources.

Moreover, in this survey we asked several questions of campaign internet users about creating and sharing political content and found:

- 8% of campaign internet users posted their own political commentary to a newsgroup, website or blog.

- 13% of them forwarded or posted someone else’s political commentary.

- 1% of them created political audio or video recordings.

- 8% of them forwarded or posted someone else’s political audio or video recordings.

Altogether, 23% of campaign internet users (or 11% of internet users and 7% of the entire U.S. population) had done at least one of those things. That translates into about 14 million people.

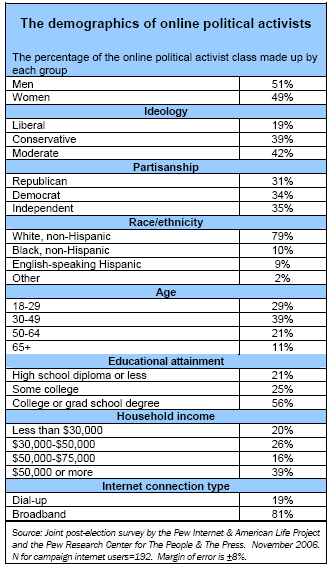

The online political activist cohort is socially upscale and tech-embracing.

This is a population disproportionately weighted towards the young, the relatively well-educated and the well-to-do. And, most notably, it is a group dominated by those who have broadband connections at home.

In their partisanship and ideology, online political activists mirror the general population of those who are civically active. However, liberals are more likely to be online political activists than conservatives. Some 15% of internet users who describe themselves as liberals are such online activists, compared with 9% of online conservatives. Online political activists as a group are evenly divided between men and women. And their racial and ethnic composition is not very different from the general population.

Online political activists are highly active and engaged citizens, not only on the internet, but in civic life in general.

Compared with many of their fellow citizens, online political activists report higher levels of interest in public life. They are heavy consumers of news in all forms. In the most recent campaign they were more likely to cite the internet as the main source of their political news than newspapers, although they were most likely to say television was their main source of political news.

They also exhibit the most aggressive use of the internet to do all kinds of political activity, from exchanging emails about the campaign, to signing up for email alerts from campaigns, to getting political news from websites outside the mainstream media, to watching video clips and assessing candidate claims and counterclaims, to donating to candidates.

Online political activists also have different information-seeking habits online. They are more likely than others to prefer going to websites that share their point of view. And they are more likely than other internet users to go to websites that are not principally fed by American news organizations.

They are also the most likely group to say that their major reasons for using the internet to get political information include getting extra information and more perspective – both in terms of local perspective and insight from beyond their community.

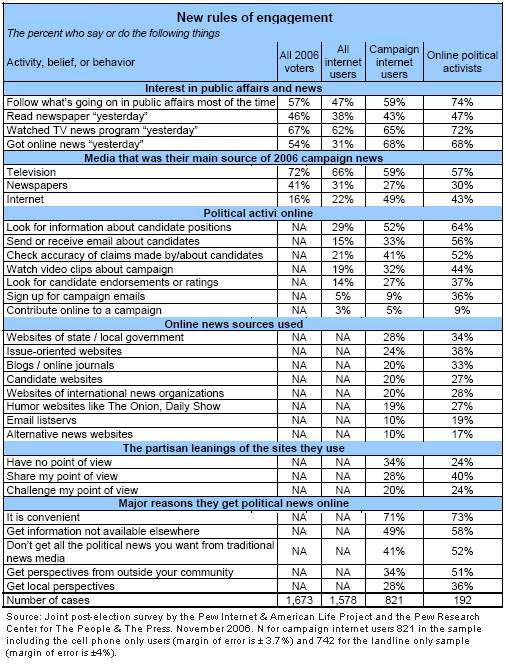

The table below highlights their special brand of activism and interest in political news from all kinds of places on the internet:

Internet users often bump into political news when they were doing other things online.

One of the realities of life online is that an internet user can encounter material through links or through general browsing that is often not related to the subject that inspired them to go online in the first place. For instance, they might go online to check sports scores or use a search engine and still run into political information that is also displayed on pages linked the ones they are using.

We have seen consistent evidence of this and the post-election survey adds more data. Some 36% of internet users (24% of the general population) say they ran across campaign news and information on the internet while they were online for another purpose. These happenstance encounters with political material were somewhat less frequent than in the 2004 election when 51% of internet users (and 31% of the general population) had this occur to them.

Voters aren’t always looking for information that supports their point of view. Many seek contrary material.

One of the major concerns about people’s use of the internet is that they might use the powerful filtering mechanisms available online and begin to shun information that does not agree with their beliefs. The Pew Internet Project studied the phenomenon of “selective exposure” in a report in 2004, which found that it does not appear to be a typical pattern of internet users.10 This new survey provides additional support for the idea that internet users are likely to encounter information that challenges their point of view.

Asked about the websites they regularly visit, a slight plurality of internet users say they prefer neutral sources; the remainder divided between their preferences for going to sites that agreed with their political views and sites that challenged their political views:

- 34% of campaign internet users say most of the sites they use sites that don’t have a particular point of view

- 28% of campaign internet users say most of the sites they use share their point of view

- 20% of campaign internet users say most of the sites they use sites that challenge their point of view

- 18% of campaign internet users did not respond to this question or say they didn’t know.