Prediction and Reactions

Prediction: As sensing, storage and communication technologies get cheaper and better, individuals’ public and private lives will become increasingly ‘transparent’ globally. Everything will be more visible to everyone, with good and bad results. Looking at the big picture – at all of the lives affected on the planet in every way possible – this will make the world a better place by the year 2020. The benefits will outweigh the costs.

An extended collection hundreds of written answers to this question can be found at:

http://www.elon.edu/e-web/predictions/expertsurveys/2006survey/transparencyandprivacy.xhtml

Overview of Respondents’ Reactions

Some level of privacy will be retained, but there is disagreement over whether this should be achieved by force of law or social contract. There is an expectation that governments and corporations will continue to escalate surveillance and “own” access to information; the powerful and privileged will benefit most from this growing availability of personal information.

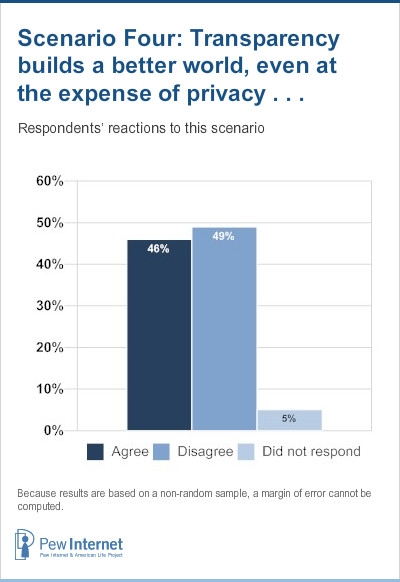

Respondents offered divided reactions to this scenario. “We will continue to have very mixed opinions about the effects of transparency and the loss of privacy, just as we do today,” predicted Gary Chapman, director of the 21st Century Project at the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas-Austin.21 “These mixed opinions are likely to intensify, meaning that there will be passionate extremes on both sides of the issue.” In this 2006 survey, while the answers were nearly evenly divided, the passion was most deeply expressed by those who disagreed with the scenario. Those who agreed generally hedged their agreement with qualifications indicating that the world would have to find ways to deal with privacy issues.

Several top leaders of the internet groups surveyed took the view that in a transparent world the benefits will outweigh the costs, but they noted that privacy must also be protected in some manner – some argued for formal mechanisms and others expected informal mechanisms to predominate.

A starting point for some respondents was a sense expressed by writer and teacher Douglas Rushkoff: “Things have never been private anyway. The most important thing about transparency is it shows how transparent people have already been, all along, to the institutions that mean to control them.”

“I generally agree,” wrote Internet Society Chairman Fred Baker. “However, privacy remains important, so I tend to think that we will find ways to limit the invasion of it. Data mining techniques and other kinds of analysis will make the globe more similar to a small town than it is now, in much the same way that the deployment of the Internet has pushed the development of McLuhan’s global village. One characteristic of a small town is that ‘everybody knows everybody’s business,’ which is to say that gossip and other activities betray confidences and otherwise invade the privacy of the people in the town. That will be one side of the global village.”

Thomas Narten of IBM, who also works as the Internet Engineering Task Force liaison to ICANN, wrote, “I generally agree, but legislation will be needed (and is probably inevitable) to curb abuses. The incentives for abuse are simply too great.”

“Between ‘agree’ and ‘disagree’ I’ll pick ‘agree,’ but I think it’s more accurate to say it could make the world a better place overall,” wrote Seth Finkelstein, EFF Pioneer Award winner. “The difference between the Open Society and the Police State is political, not technological.”

Glenn Ricart, a member of the Internet Society Board of Trustees, wrote: “There will be higher degrees of transparency, but this will arise from a change in social norms and ultimately come from voluntary compliance … Look at taking cell phone calls. A decade ago, no one would have interrupted a personal conversation to answer a ringing desk telephone. Today, however, people provide lots of transparency into their lives by answering their cell phones anywhere and everywhere. It’s being done so often that it’s becoming culturally acceptable. And, even if you don’t answer your phone, it’s still OK to SMS someone even while your attention was assumed to be elsewhere. IM ‘away’ messages and more … all make me believe that people will continue to surrender certain parts of their privacy for what they perceive to be benefits of interaction. However, I’m a staunch believer that we need to retain the ‘off’ button. People should be able to opt out of transparency, and I believe they will do so increasingly as a form of vacation or holiday or de-compression. Some new name will attach to this phenomenon. (‘Turning-off’?)”

Matthew Allen, president of the Association of Internet Researchers and a professor at Curtin University in Australia, tackled today’s definition of the concept of privacy in the world’s democracies. “Privacy has been asserted as a right within the modern Western paradigm that has come to dominate our perceptions of what ‘ought’ to be,” he wrote. “In fact, privacy is not a right but a state of engagement with the world. Technologies that interlink people (whether they be telephones, ships, or computing and the Internet) bring people into proximity and thus into a realm of less privacy.”

Australian internet pioneer Ian Peter wrote: “The benefits are enormous in enabling communication across an inter-connected planet. The potential problems this may give rise to in areas such as privacy do need to be addressed carefully, though, and the benefits will only be as great as our governments and societal attitudes allow. If we do not learn to behave more compassionately and sensibly as global citizens, no amount of connectivity will make up for this (although it may help to bring it about).”

One simple strategy for coping in a world of more enabled surveillance same from Bob Metcalfe, founder of 3Com, now of Polaris Venture Partners: “The trick is not to do anything you’re ashamed of.”

Chris Sorek, former director of global communications for Red Crescent and Red Cross, now with SAP, wrote, “Without transparency there can be no ‘level playing field’; competitive and open environments build economies and communities. This, in turn, enables everyone to have a fair chance to succeed and prosper.”

Tiffany Shlain, founder of the Webby Awards, wrote, “Giving all people access to information and a context to understand it will lead to an advancement in our civilization.”

And Christopher Johnson, co-founder and CEO for ifPeople, wrote, “I am optimistic about the ability of the public to maintain control of the information that is generated, despite the current trend in secretive government information control. If the public has control, the benefits will outweigh the costs. If powerful groups have control and use of the information, it will further greed, discrimination, and infringement of privacy.”

There is plenty of pessimism, though, about prospects for transparency.

Some respondents expressed deep concerns about losses of privacy. Naturally, many of them are deeply attuned to the issues involved because they represent civil liberties organizations.

The answer was a clear “disagree” for Marc Rotenberg, executive director of the Electronic Privacy Information Center. “The cost of unlimited transparency will not simply be privacy,” he wrote. “It will be autonomy, freedom, and individuality. The personal lives of prisoners are transparent. So, too, is the world of the Borg.”

Sharon Lane , president of WebPageDesign, was also forceful in her reply. “It will NOT be a better world,” she wrote. “It will be an Orwellian world! The benefits most certainly will not outweigh the costs.”

Robin Gross, executive director of IP Justice, a civil liberties organization that promotes balanced intellectual property law, wrote, “The cost to privacy will be greater than we expect.”

Barry Wellman, a researcher on virtual communities and workplaces and the director of NetLab at the University of Toronto, responded, “The less one is powerful, the more transparent his or her life. The powerful will remain much less transparent.” Lisa Kamm, an IT professional who has worked for IBM and the ACLU, wrote, “Privacy should remain a critical value and a right, and while there are benefits that come with increased transparency, they do not outweigh the costs.”

Alejandro Pisanty, vice chairman of the board for ICANN and a member of the United Nations’ Working Group for Internet Governance, built his own scenario: “Transparency builds a much worse world, at the expense of privacy and security. The benefits will not, or hardly, outweigh the costs. The situation will be dramatically worse in societies (countries or not) in which democratic governance is weak.”

That kind of imbalance is what worries Gwynne Kostin, director of Web communications at the U.S. Department of Homeland Security: “There are bad guys out there ready to exploit these vulnerabilities. There may be a giant technical step backward caused by privacy concerns.”

Forecaster and strategist Paul Saffo, director of the Institute for the Future, says the scenario is “a utopian overstatement.” He explained: “It underestimates the intrinsic flaws in the technology, and the capacity of clever people to subvert the system for selfish ends. The sensor society will be a mixed bag of real benefits and real cost in terms of lost freedoms. That said, we must press for transparency at every opportunity. The only way to control Big Brother is for all the little brothers to watch back. The most we can hope is that we will be able to find a reasonable balance between privacy and the need to know.”

Michael Cannella, a member of Computer Professionals for Social Responsibility and an IT manager for Volunteers of America, wrote, “This ‘transparency’ will result in loss of liberty and privacy for individuals but will not give the individual human any more information about nor control over the consolidation of power in non-governmental hands, such as multinational corporations. This will partially be a result of misinterpretation (by governments already beholden to these powers’ and their interests) of the power of free markets to maximize all possible goods (including social and cultural). This outlook: ignores the reality of collusion, market manipulation and other limitations; overlooks the power money holds over politics (bribery, lobbying); forgets our historical lessons about relying on the ‘invisible hand of the market,’ and the strengths of putting other values before money in market management.”

A number of the survey respondents expect that information will often flow just one way.

Some respondents mentioned “Big Brother” and “1984” in their answers in reference to George Orwell’s dystopian novel. Most just predicted that transparency will not be equitably applied. Esther Dyson of CNET, founding director of ICANN, wrote, “The world is not average, and the benefits and costs will not be evenly distributed.” Alex Halavais, an internet researcher and assistant professor at Quinnipiac University, responded, “Recent events seem to indicate that reciprocal transparency is hardly an obvious future.”

Steve Cisler, founder of the Association for Community Networking, put this in the context of double bookkeeping: “Certain groups that have maintained secrecy to guard their power (shamans, governments that are autocratic or kleptocratic, criminals) will continue to do so. There may be double bookkeeping of sorts: a private face and record, and a supposedly open and transparent spin for public scrutiny.”

Denzil Meyers, founder and president of Widgetwonder, responded, “The general populace will have the experience noted above, but there are always ways to commit subterfuge for those who are so motivated. We will get lulled into a sense of false security and transparency, allowing the unethical to operate even more quietly than they do now; corporations will be the biggest offenders/danger.”

And Michelle Catlett of Edubuilder wrote, “The loss of individual privacy will be controlled by the companies and governments that can afford to utilize the massive resources to manipulate the information. This won’t be used to benefit the individual. Transparency isn’t going to be two-way; individuals will not have access to information about governments or large companies in the same way.”

David Elesh, a sociology professor at Temple University, was one of several respondents to propose that people will be able to hide their information for a price or buy an identity. “What will happen,” he wrote, “is that those who can afford to do so will create ‘managed lives’ to convey the impressions that they wish to. This is true now for a thin elite, but it will diffuse.” Hernando Rojas, a Colombian communications researcher for the United Nations Development Program, agreed, writing: “Privacy becomes commodified, so yes maybe more transparency, but not overall transparency.”

In reaction to the prevailing assumption that those in power will try to escape being open to scrutiny, John Browning, co-founder of First Tuesday, a global network dedicated to entrepreneurs, wrote, “The global village metaphor holds true here. In villages, everybody knows everybody else’s business. The security lies mainly in that, in a village, you know who’s trying to find out about you. Governments and privacy advocates need to work to ensure mutual transparency.”

There ought to be a social contract – or a better technology regime on the privacy front.

Internet policy makers are already thinking along the lines Browning suggested in his response. Robert Shaw, internet strategy and policy adviser for the International Telecommunication Union, said there will be a worldwide movement to protect privacy. “Privacy will be seen more and more as a basic human right,” he wrote, “and there will be growing pressure to define this in an international instrument or convention and to have states enforce it through national legislation and regulation.”

Boing Boing blogger Cory Doctorow, an EFF Fellow, wrote, “Transparency and privacy aren’t antithetical. We’re perfectly capable of formulating widely honored social contracts that prohibit pointing telescopes through your neighbours’ windows. We can likewise have social contracts about sniffing your neighbours’ network traffic.” And Hal Varian of Google and the UC-Berkeley wrote, “Privacy is a thing of the past. Technologically it is obsolete. However, there will be social norms and legal barriers that will dampen out the worst excesses.”

Robin Berjon, a technology developer working with the World Wide Web Consortium and Expway, wrote optimistically about the development of technology solutions to protect privacy: “I am convinced that as transparency becomes increasingly visible as an issue to the general public, solutions will be developed to handle the problems it causes while at the same time maintaining as much as possible of the information infrastructure. This relies on a number of technologies such as identity, web of trust, etc., that we have a crucial need to create very soon.”

As people weigh costs v. benefits, some see virtues in the open-view world and others see problems.

Daniel Conover, new-media developer for Evening Post Publishing, responded, “The future of intrusive informatic systems will allow participants in private corporate internets access to all sorts of wonders, but their lives will be wide open to paying vendors. Most people will choose this lifestyle, and will continue to choose this lifestyle so long as the tradeoff between ‘smart suggestions’ and ‘intrusiveness’ breaks in their favor. Most people will not care to look back through the glass so long as their luxuries and entertainments continue to flow in ever-improving streams. Meanwhile, on the Open Source side of the culture, two-way transparency will change expectations of privacy and public life. Some aspects of life will become more guarded, and laws will require that specific permission be granted before certain types of information can be added to the data stream (think HIPAA). Most Americans, however, will trade waivers of those privacy rights for ‘better’ products and free access to media. And while Open Source culture will be a minority culture, it will include a vibrant mediascape. Because of its innovative and creative power, the two-way transparency of the Open Source networks will continue to influence the larger culture, even as expressed in the proprietary nets.”

Perhaps today’s youth will have different views about the tradeoffs between transparency and privacy, according to Martin Kwapinski, senior content manager for FirstGov, the U.S. Government’s Official Web Portal. He wrote: “We are facing a tidal wave of new thought on this issue. That is, people who are now, and will be coming into their maturity in the next 15 years live in a very different technological environment, and the old meanings of such concepts as privacy are rapidly changing. Younger people seem to be less concerned with keeping private things private!”

Lynn Schofield Clark, director of the Teens and the New Media@Home Project, predicted that viable oversight groups will continue to be vital to the successful protection of privacy in the coming years of increasing transparency. “I am not sure that we as a society will place enough value on this watchdog role to underwrite the costs to continue to pursue lengthy investigations and legal action. It is incumbent on those of us in education and public life to continue to place a value on this watchdog and investigative role … and to continue to push for increased accountability structures, understanding that these must be continually updated so as to keep pace with the changes that technology allows.”

Here is the current status of surveillance issues today.

Your life is being recorded in various ways today. Your cell phone is a tracking device. Your personal life and financial status are recorded in various databases. Anyone in the world can find out the tax-assessed value of your home with a 10-second internet search. And, with the further development of “IP on everything,” the concept that people and goods will be tagged and trackable on the network through the use of sensors, things are becoming more complex and more transparent simultaneously.

Billions of radio frequency ID (RFID) tags are already in use due to their growing adoption by retailers (such as Wal-Mart) and government agencies (such as the U.S. Department of Defense). The fairly inexpensive, nearly invisible devices are used as a means to improve efficiency. They can be used to track inventory, equipment and personnel; they may replace bar codes. One estimate finds that corporations making RFID devices will make more than $24 billion a year by 2016.

At this point in their development, the information that is captured or transmitted by these tiny devices has little or no security – no screens or firewalls. A report released by researchers at Vrije University in Amsterdam in March 2006 raised concerns that RFID tags might be altered without a user’s knowledge and utilized as a transmission medium for computer viruses, noting that the limited storage buffer of such tags (ranging from 90 to 100 bytes) could allow bad code a place to lurk and then enter the network.

A bigger concern is the surveillance applications implicit in the devices. In late May the U.S. Department of Homeland Security issued a 15-page draft report that expresses concerns over the potential use of RFID in identification cards or tokens for illegal tracking of people. “Miners or firefighters might be appropriately identified using RFID because speed of identification is at a premium in dangerous situations,” the report reads, “… but for other applications related to human beings, RFID appears to offer little benefit when compared to the consequences it brings for privacy and data integrity.”

Bills regulating RFID tags have been proposed in at least 19 states, and Wisconsin passed a law that took effect in June stipulating that no person may force another to have a microchip implanted in his body. Several nations have begun to embed RFID devices in passports – the U.S. has tested this and is implementing it this summer and fall, despite complaints that the passports can be “read” by anyone with special equipment from 30 feet away.

Concerns have been raised because at this point it is easy to steal or modify data contained on most RFID chips. It is expected the RFID signals sent by U.S. passports will be encrypted.22

The internet is no longer a private, borderless network.

The governments of China and other non-democratic nations are exerting more controls and surveillance all the time over the internet – once considered to be a perfect conduit for anonymous communications. This is explained well in the book Who Controls the Internet?, by law professors Jack Goldsmith and Tim Wu. In it, they write: “[China] is trying to create an internet that is free enough to support and maintain the world’s fastest growing economy yet closed enough to tamp down political threats to its monopoly on power.”23

They cite the example of Liu Du, a 22-year-old university student whose 2002 online essay titled “How a national security apparatus can hurt national security” caused her to be jailed in a cell with a convicted murderer. When concerned supporters protested on her behalf, five of them were arrested. Liu Du was held for a year and released, but she is not allowed to leave Beijing, she is not allowed to speak to foreign journalists, and she is now under permanent surveillance. Alaa Seif al-Islam was arrested in May 2005 for protesting the beating of women at a pro-democracy rally in Cairo. Seif al-Islam is still in jail, and at least six additional bloggers were arrested for protesting Egyptian government policies in May 2006.24

China reportedly employs as many as 50,000 internet investigators who conduct online surveillance, erasing commentary, blocking sites, and authorizing the arrests of people for any communication that is seen to be unpatriotic. In addition it has begun to employ thousands of university students as volunteer internet monitors – the project is named “Let the Winds of a Civilized Internet Blow,” and it is part of a broader “socialist morality” campaign, known as the Eight Honors and Disgraces.25 Records from a court case in China showed that Yahoo may have been involved in identifying the email account of a dissident writer; Reporters Without Borders announced in April that this is at least the third incident of this type involving Yahoo. Google co-founder Sergey Brin acknowledged in June that his company has compromised its principles by accommodating censorship demands from the Chinese government. Brin told reporters in Washington, D.C., that Google agreed to the censorship only after Chinese authorities blocked its service. The popular search service is now accessible only through the censored site Google.cn.26

China isn’t the only nation convincing people to participate in voluntary spy service. In another instance of a government recruiting people as active participants in surveillance, Texas governor Rick Perry announced a $5 million plan in June to install hundreds of night-vision cameras along the Mexican border, run live the video feeds on the internet, and encourage anyone with a computer who spots illegal immigrants trying to enter the U.S. to call a toll-free number and turn them in – it’s called a “virtual posse.”

In these and other less-public cases, governments and corporations are working – sometimes in league with one another – to spy on people, some of whom are being arrested and jailed. In order to convince internet companies to help, in many cases (China for one) governments threaten a loss of access (this equates to a loss of corporate income) if the companies don’t follow their wishes in regard to censorship, the sharing of the personal computing records of protesters, and the sending of “tracing” packets out on the network to identify the location of wanted users.

Filtering, network tracing technology and geo-identification were developed to help all nations fight online fraud and other crimes, to help certain nations retain their cultural identity (France is a leader in this regard) and to help corporations and other groups share information selectively on a regional level. Goldsmith and Wu write in Who Controls the Internet? that the firewalling of nations is becoming more sophisticated as the newest internet geo-ID technologies are allowing companies to tailor content by geography and avoid sending content to places where it is not legal.

A new battlefield: Who can have access to what data?

Surveillance issues are not limited to non-democratic nations. In a May 2006 preliminary discussion, the FBI suggested that U.S. internet providers consider putting the storage capacity in place to retain their customers’ Web-use records for up to two years in order to aid investigations into terrorism, child pornography, and other crimes. FBI and U.S. Department of Justice officials met formally with top internet executives from Google, Microsoft, AOL and other companies in an initial discussion of the request. At this point in time, internet companies generally keep such information as sites visited, email contacts, and downloads for a period of a few days to a few weeks, and the government generally does not have any access to these records. Several internet firms have cooperated by opening records in specific government investigations of pornography and terrorist activity when subpoenaed in the past.

Earlier this year, the Department of Justice and National Security Agency were heavily criticized by privacy proponents for allegedly requesting access from U.S. companies to the phone and internet records of virtually all U.S. customers. U.S. law currently holds that court orders can be issued to require internet companies to turn over records when they have them, but the internet records needed to prove a case are generally erased before they are of use in court. In March, Google was ordered by a U.S. District Court to give the U.S. government a randomly generated selection of 50,000 indexed Websites to test internet filters. The Department of Justice had originally asked for several months of keywords and search results; Google refused, spurring the court action that led to a reduced request, but one that was fulfilled.

Data exposure makes headlines weekly and nearly daily, as personally sensitive data collections stored in corporate and government databases and on digital media are lost or stolen on a regular basis. A famous example: privacy advocates made public the Social Security numbers of then-Rep. Tom Delay and Florida Gov. Jeb Bush, both found easily online on county Websites. Another more recent example: AOL’s release of the details of all online searches conducted over a period of time by a large sample of its customer base during the summer of 2006.

Sometimes the data isn’t stolen or lost by accident. Some companies have been accused of improperly sharing it for a profit. Gratis, a Washington-based corporation, was sued in March 2006 by the state of New York for selling the personal information of millions of people to email marketers.