Prediction and Reactions

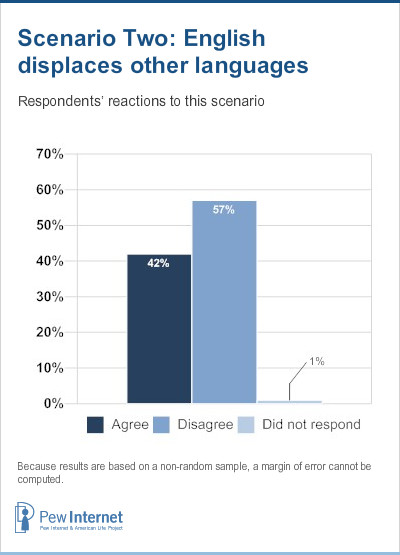

Prediction: In 2020, networked communications have leveled the world into one big political, social, and economic space in which people everywhere can meet and have verbal and visual exchanges regularly, face-to-face, over the internet. English will be so indispensable in communicating that it displaces some languages.

An extended collection hundreds of written answers to this question can be found at:

http://www.elon.edu/e-web/predictions/expertsurveys/2006survey/englishtoplanguage.xhtml

Overview of Respondents’ Reactions

English will be the world’s lingua franca for cross-culture communications for at least the next 15 or 20 years; Mandarin and other languages will continue to expand their influence, thus English will not ‘take over’; linguistic diversity is good, and the internet can help preserve it; all languages evolve over time.

Until translation technology is perfected and pervasive, people must find other ways to communicate as effectively as they can across cultures. A lingua franca is a common language for use by all participants in a discussion. At this point, the world’s lingua franca is English – for example, it has been accepted as the universal language for pilots and air-traffic controllers. But English-speaking nations have an estimated population of just 400 million out of the 6 billion people in the world. If the pendulum swings to a different dominant language, or two or more overwhelmingly dominant languages, it would bring powerful change.

Thomas Keller, a member of the Registrars Constituency of ICANN and employee of the Germany-based internet-hosting company Schlund,10 spoke for many with this prediction: “The net of the future will very likely evolve more into a big assembly of micro webs serving micro communities and their languages.”

Another common view was captured by Mark Rotenberg, executive director of the Electronic Privacy Information Center: “Two powerful trends will collide: English will become more prevalent as American culture and technology flow out across the world, but critical mass will also be achieved for global communications in Spanish, Mandarin, Japanese and Arabic as new internet protocols which support International Domain Names are more widely adopted.”

Many who disagreed with domination by English in this 2020 scenario generally acknowledged that English is a common “second-language” of choice but said they expect many users of the internet will mostly use the language of their own cultures in online communications. Many expressed enthusiastic support of another language – such as Mandarin Chinese – supplanting English within the next 15 years, while others agreed that English will be important but not dominant. Some speculated that by 2020 innovators will build some sort of translating function into the internet to make it technologically possible for everyone to speak and write in their native languages while being easily understood by people across the globe.

“English will not, alone, predominate. However, many smaller language groups will give way to a general reliance on one of several large languages such as English, but also Spanish, French, and variations on Chinese,” argued Matthew Allen, Curtin University, Australia, president of the Association of Internet Researchers.

Fred Baker, chairman of the board of trustees for the Internet Society, wrote, “To assert that we will therefore have a large English-only world doesn’t follow; Mandarin, German, Spanish and many other languages will continue to be important.” And Seth Finkelstein, anti-censorship activist and author of the Infothought blog, wrote that this scenario is “much too ambitious. There will still be plenty of people who will have no need for global communications in other languages, or who choose to communicate only within their local community.”

“First the premise that networked communications will have developed to this point is false,” maintained Robin Lane, educator and philosopher, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. “Second it is a fact that English has been indispensable for international communications for the last century – a fact that has not led to English displacing other languages. It is, and will continue to be, layered on top of the native language of the user of intercultural communications.”

Never has there been a language spoken by so many.

11Linguist David Crystal has estimated in his research that the world has 140 languages in use by at least a million people each. He says there has never in the history of the world been a language spoken by so many people as English is today, adding that as many as 1.5 billion people speak English as a first or “added” language, and the number could exceed 2 billion by 2020.The respondents who agreed with the survey’s 2020 language scenario generally noted that English is already a pervasive “second” language – used as a tool of diplomacy, education and business around the world – and it is also the language of the originators of the internet, and is thus most likely to continue to dominate.

“English will be well on the way to being the world’s most popular second language (by 2020),” wrote Hal Varian, dean of the School of Information Management & Systems at UC-Berkeley and a Google researcher. “Mandarin is a contender, but typewriter keyboards will prevent it from really taking over from English.”

“The leveling effect is already quite visible,” wrote Glenn Ricart, Internet Society board member employed by Price, Waterhouse Coopers; formerly of DARPA. “It seems paradoxical that the Internet can be a powerful force for memorializing and evangelizing local languages and cultures and differences and still lead to a great homogenization as the thirst for knowledge leads one invariably into Chinese and English. In 2020, many more people will be bilingual, with working web-interaction knowledge of English to go with their native tongue.”

Jim Warren, founding editor of Dr. Dobb’s Journal and a technology policy advocate, agreed that the issue of interface construction plays a role. “English has already become the mandated standard language … most keyboards around the world are the ASCII character set,” he wrote. “The accent characters of other Western languages require special finger contortions, and it seems certain that the world will NOT standardize on any of the more complex character sets of the East, much less the pictograms of Asia … it’s only 15 years to 2020.”

Language choices will be context-specific, much as they are today.

There was a suggestion in some answers that language preferences might shift and accommodate, even as English was sweeping the internet. A typical iteration of this idea came from Esther Dyson, former chair of ICANN, and now of CNET Networks: “Yes, English will ‘displace’ some languages, but there will be, for example, much more Chinese. People pick their language according to whom they want to communicate with, and there will be many different communities with (still) many different languages.”

Paul Saffo, forecaster and strategist for the Institute for the Future, responded that the scenario is actually a “present-tense description.” He added: “Badly-accented English is to global society today what Latin once was to Western society long ago. English will continue to advance, BUT the real question is whether this trend will peak in the next two decades, and I believe it will. English’s acceptance will reach a certain high-water point not terribly larger than its penetration today. Then things will get interesting.”

“English is going to be the common language,” wrote internet pioneer David Clark of MIT, “but we will see an upsurge in use and propagation of local languages. For many users, their local language will still be the only language they use on the Internet. And of course, for low-complexity uses, we will see more translation.”

Internet growth in non-English-speaking countries will affect the language used online.

While internet-usage demographics are inexact, most measurement experts agree that North American dominance in regard to Web-content-building and total usage of the internet ended a while ago, with only about one-fourth of internet users hailing from the U.S. or Canada at this point in time.

While there are other nations in which English is a dominant language, including the United Kingdom and India (where Hindi and English are officially used), the nations where internet growth will see the most progress in the next few years are situated primarily in Asia; the expectation is that China will have the world’s largest internet population within the next five years.

“Sure, English will displace some languages,” wrote Howard Rheingold, the internet sociologist and author. “But as the century advances, Chinese becomes more dominant, strictly because of demographic drivers.” Former InfoWorld editor Stewart Alsop wrote: “English will not displace or replace the other major languages in the world, including French, Spanish, Japanese, Germanic, Hindu, etc.” And communication technologies researcher Mark Poster wrote: “Chinese might be emerging as the new lingua franca.”

International Domain Names will change the landscape.

The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers has been urged for years to find a way to initiate the use of non-English top-level domain names – at this point in time, roots (such as .com, .org, .net) are only used in English (and the Roman character set). ICANN was established in 1998 to oversee technical details regarding web addresses – the Domain Name System. It is an international body working at sorting out worldwide networking details for a technology established by English-speaking people. There has been some fear that other nations, frustrated with ICANN’s slow progress toward opening its system to other languages, might split off into nation-state networks with their own naming schemes rather than staying tied to the global network. ICANN officials agreed in March to begin to test the use of international domain names written in local character sets in July of 2006.12

Scott Hollenbeck, IETF director and a leader for internet infrastructure-services company VeriSign, reflected the politics of root addresses in his survey response. “While I do believe English will continue to be the predominant language used for ‘across-the-network’ human communication,” he wrote. “I do not believe that it will be ubiquitous by 2020. In 2006 there are efforts to localize Internet protocols in a way that will likely create islands of non-English communication capabilities. These efforts will continue and will gain traction in communities where English is not spoken by a large portion of the population.”

Bret Fausett, a partner with a U.S. law firm and producer for ICANN.Blog, wrote, “In 2005, we’re at the peak of the English language on the internet. As internationalized domain names are introduced over the next few years, allowing users to conduct their entire online experience in their native language, English will decline as the central language of the internet.”

Alan Inouye, a U.S. internet policy analyst, agreed. “I would say ‘displace’ is not likely. English will continue in its role as the de facto international language. However, there are countervailing forces against English language dominance on networks. Networks such as the internet facilitate the development of communities of common interests and languages among people who may be widely dispersed geographically. Also, we will see a dramatic increase in Chinese-language content.”

Many expect translation technology to improve greatly.

At this point, computer-based translation is still in early development, and despite improvements it lags far behind the ability of a good human translator. Some respondents who questioned the likelihood of the 2020 language scenario did so because of their belief that technology innovators will have found a way to bridge the gaps in intercultural communication.

One person with such confidence is pioneering internet engineer and Internet Architecture Board and Internet Society leader Christian Huitema, who wrote, “Computer technology increases the frequency of communication, which creates a desire to communicate across boundaries. But the technology also enables communication in multiple languages, using various alphabets. In fact by 2020 we might see automatic translation systems.”

Marilyn Cade, of the Information Technology Association of America and the Generic Names Supporting Organization of ICANN, wrote, “English may be the default ‘universal’ language, but we will see a rise of other languages, including Chinese, French (francophone Africa) and other languages supported by technological translation – at last!”

The internet can help preserve languages and cultures.

Many survey respondents pointed out that the internet is actually helping to halt the complete disappearance of some languages and it is even being used to revive those that were considered to be “dead.”

Previous 20th century communications technologies were principally responsible for what researcher Michael Krauss of the Alaska Native Language Center said in 1992 is “electronic media bombardment, especially (by) television – an incalculably lethal new weapon which I have called ‘cultural nerve gas’.”13 But today the internet is being used for “RLS” – reversing language shift – projects. For instance, the Tlingit language of the Inuit people in southeast Alaska has been preserved in an online database used by schoolchildren in Glacier Bay. More places are seeing the development of indigenous-language projects and databases online. Broadband allows the use of richly detailed audio and video files on such sites – allowing depth of detail in pronunciation and in facial and other physical movements associated with the languages to become a part of the record.

Survey respondent Steve Cisler, a former senior library scientist for Apple now working on public-access internet projects in Guatemala, Ecuador and Uganda, wrote: “Indigenous languages will have a hard time changing to accommodate the impact of popular media languages, though more people will use ICT to try to revitalize some languages or spread the use of them outside of local places.”

Michel Menou, a professor and researcher in information science who was born in France and has worked in nearly 80 nations, replied that while linguistic diversity is increasing on the internet, the challenges to their survival still remain. He added what the internet will do is “offer new options for their preservation, teaching and use.”

And John Quarterman, president of InternetPerils Inc. and the publisher of the first “maps” of the internet, wrote: “Internet resources will permit some languages to thrive by connecting scattered speakers and by making existing and new materials in those languages available.”

Internet influences might create new dialects in the English language.

Several respondents noted that English itself is likely to see some changes in the next 15 years, as globalization and new communications-content delivery systems alter cultural needs.

Bruce Edmonds of the Centre for Policy Modelling in the United Kingdom observed, “1) Technology will allow considerable interoperability between languages, making a single language less necessary. 2) As in all evolutionary systems, very successful, dominant species spawn subspecies; English will continue to fragment into many sublanguages.”

Bob Metcalfe, inventor of Ethernet, founder of 3Com, and now with Polaris Venture Partners, wrote, “Of course, a lot of 2020 English will sound Mandarinish.” Paul Saffo of the Institute for the Future wrote: “Mandarin will of course grow dramatically, but I believe we will also see the rise of divergent English dialects.”

Michael Gorrell, senior VP and CIO for EBSCO, wrote, “Some internationalized variation of English will evolve. Internet and instant messenger-based acronyms will grow into everyday use, fwiw. This new slang will be combined with new words and concepts – like blog, wiki, chat – to form a new ‘net dialect’ of English.”