Prediction and Reactions

Prediction: By 2020, worldwide network interoperability will be perfected, allowing smooth data flow, authentication and billing; mobile wireless communications will be available to anyone anywhere on the globe at an extremely low cost.

An extended collection of hundreds of written answers to this question can be found at: http://www.elon.edu/e-web/predictions/expertsurveys/2006survey/globalnetworkthrives.xhtml

Overview of Respondents’ Reactions

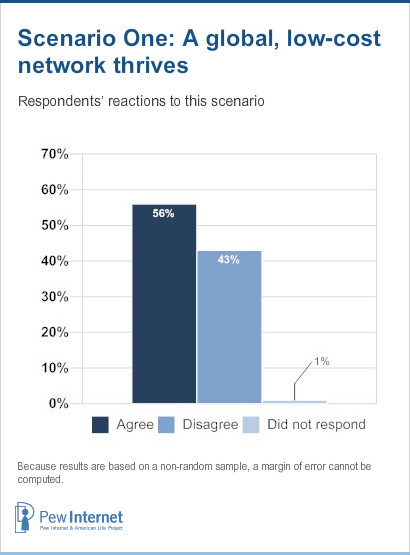

A great deal of innovation, investment of resources and successful collaboration will have to be accomplished at the global level over the next 15 years for the elements of this proposed scenario to unfold in a positive manner. A majority of respondents agree with this optimism, while there is vocal disagreement among a significant minority.

A majority of those who chose to “agree” with this scenario did so while expressing some reservations about parts of our formulation of it. Some suggested that government and/or corporate control of the internet might limit some types of access in certain parts of the world, and others noted a likely lack of “perfected” interoperability in a world of changing technology. Some who supported this scenario presumed that certain technology innovations, such as mobile computing, would accelerate and solve problems that are tough to address now.

“The advances in wireless technologies are pretty much a natural consequence of Moore’s law,” wrote Christian Huitema, a longtime Internet Society leader and a pioneering internet engineer.5 “Better computers mean more advanced signal processing, and the possibility to harness higher frequencies. More frequencies mean an abundant ‘primary resource,’ thus natural competition increasing service availability and driving down prices.”

Bob Metcalfe, internet pioneer, founder of 3Com and inventor of Ethernet, now of Polaris Venture Partners, chose to reflect on the arrival of “IP on everything,” the idea that networked sensors and other devices using an internet protocol (IP) will proliferate. “The internet will have gone beyond personal communications,” by 2020, he wrote. “Many more of today’s 10 billion new embedded micros per year will be on the internet.”

Louis Nauges, president of Microcost, a French information technology firm, sees mobile devices at the forefront. “Mobile internet will be dominant,” he explained. “By 2020, most mobile networks will provide 1-gigabit-per-second-minimum speed, anywhere, anytime. Dominant access tools will be mobile, with powerful infrastructure characteristics (memory, processing power, access tools), but zero applications; all applications will come from the Net.”

Mobile devices are a key to global connection.

Hal Varian, dean of the School of Information Management & Systems at the UC-Berkeley and a Google researcher, generally agrees with the scenario. “I think this could easily happen,” he wrote. “Of course, some of the mobile access could be shared access (a la Grameen Phone)6 but, even so, I would guess that most people in the world could get on the network if they really wanted to by 2020.”

John Browning, co-founder of First Tuesday and a writer for The Economist, Wired and other technology/economics publications, sees many improvements in networking and devices in the next 15 years. “[The system won’t be] perfected and perfectly smooth, but certainly more, better and deeper than today,” he wrote. “The biggest change will come from widespread and reliable identification in and via mobile devices. The biggest source of friction will be copyright enforcement and digital rights management. There will be much innovation in devices to match form and function, media and messages.”

Michael Reilly of Globalwriters, Baronet Media LLC, predicted that “mobile technologies facilitated by satellite” will reach out to all people. “Sat-nets will be subsidized by the commercial lines of interest that promote all kinds of brand expansion,” he predicted. “Non-profits also will use these technologies to provide services and support as well as to help bridge divides such as the Islamic and Judeo-Christian worlds. The Rockefeller Brothers Fund, to name one, is working on the first stages of this now.”

Respondents argue that internet carriers and regulators must work together to make a low-cost network to come to fruition.

Rajnesh Singh of PATARA Communications, GNR Consulting and the Internet Society for the Pacific Islands, qualified his agreement with the proposed scenario. “The issue governing whether this happens completely and really ‘worldwide,’” he wrote, “will depend on the various telecom carriers and regulators around the world taking the necessary steps to effectively relinquishing control of their in-country networks. This may not be completely practical in developing countries, as it will severely impact the revenue model of the incumbent carrier that is typically government-owned. For the ‘developed’ world, this prediction is indeed a reality we may end up experiencing.”

Andy Williamson, managing director of Wairua Consulting in New Zealand, agreed: “The technical and social conditions for this will most likely exist … my hesitation is that I do not see a commitment from national legislatures and from international bodies to control commercial exploitation of networks. For your prediction to come true, global regulation of networks that privileges public good over commercial reward must occur.”

Alik Khanna, of Smart Analyst Inc. in India, sees a low-cost digital world ahead. “With growing data-handling capacity, networking costs shall be low,” he wrote. “The incremental efficiency in hardware and software tech shall propel greater data movement across the inhabited universe.”

Some experts express doubts about a “networking nirvana.”

A vocal minority disagreed with the positive scenario for network development, most of them questioning the ideas of interoperability and global access at a low cost. They also noted the necessity for government and corporate involvement in worldwide development and the political and profit motives that usually accompany such involvement.

“Companies will cling to old business models and attempt to extend their life by influencing lawmakers to pass laws that hinder competition,” argued Brian T. Nakamoto, Everyone.net. And these views were echoed by Ross Rader, director of research and innovation for Tucows Inc. and council member for the Generic Name Supporting Organization of the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers, the international body tasked with assigning internet domain names and IP addresses: “By 2020, network communications providers will have succeeded in Balkanizing the existing global network, fracturing it into many smaller walled gardens that they will leverage to their own financial gain.”

“While society as a whole would be likely to benefit from a networking nirvana, the markets are unlikely to get there by 2020 due to incumbent business models, insufficient adoption of new cost-compensation methods, and insufficient sociotechnical abilities to model human trust relationships in the digital world,” wrote Pekka Nikander of Ericcson Research, the Internet Architecture Board and the Helsinki Institute for Information Technology.

Ian Peter, Australian leader of the Internet Mark II Project, wrote: “The problem of the digital divide is too complex and the power of legacy telco regulatory regimes too powerful to achieve this utopian dream globally within 15 years.”

Peter Kim, senior analyst with Forrester Research, agrees. “Profit motives will impede data flow,” he wrote. “Although interconnectivity will be much higher than ever imagined, networks will conform to the public utility model with stakeholders in generation, transmission, and distribution. Companies playing in each piece of the game will enact roadblocks to collect what they see as their fair share of tariff revenue.”

Will there be a new or different network by then?

Fred Baker of Cisco Systems, chairman of the board of the Internet Society, posed the possibility that “other varieties of networks” might “replace” the current network, “So, yes,” he wrote, “I suspect there will be a global low-cost network in 2020. That’s not to say that interoperability will be perfect, however. There are various interests that have a vested interest in limiting interoperability in various ways, and they will in 2020 still be hard at work.”

One of the key actors in the development of another “variety of network” is David Clark of MIT. Clark is working under a National Science Foundation grant for the Global Environment for Networking Investigations (GENI) to build new naming, addressing and identity architectures and further develop an improved internet. In his survey response, Clark expressed hope for the future. “A low-cost network will exist,” he wrote. “The question is how interconnected and open it will be. The question is whether we drift toward a ‘reintegration’ of content and infrastructure.”

Bruce Edmonds of the Centre for Policy Modelling at Manchester, UK, expects that continuous changes wrought by the evolution of internet architecture will remove any chance for a “perfected” or “smooth” future. “New technologies requiring new standards,” he predicted, “will ensure that (1) interoperability remains a problem, and (2) bandwidth will always be used up, preventing smooth data flow. Billing will remain a problem in some parts of the world because such monetary integration is inextricably political.”

Many see corporate and government restrictions in the future.

Many of the elaborations recorded by those who disagreed with the 2020 operating environment scenario express concerns over the possibility that the internet will be forced into a tiered-access structure such as those now offered by cellular communications providers and cable and satellite television operators. Mark Gaved of The Open University in the UK sees it this way. “The majority of people will be able to access a seamless, always-on, high-speed network which operates by verifying their ID,” he predicted. “However there will be a low-income, marginalised population in these countries who will only have access to limited services and have to buy into the network at higher rates, in the same way people with poor credit ratings cannot get monthly mobile phone contracts but pay higher pay-as-you-go charges.” He also predicted that some governments will limit citizen access in some less-democratic states.

Scott Moore, online community manager for the Helen and Charles Schwab Foundation, wrote: “New networks will be built with more controllable gateways allowing governments and corporations greater control over access to the flow of information. Governments will use the excuse of greater security and exert control over their citizens. Corporations will claim protection from intellectual property theft and ‘hacking’ to prevent the poor or disenfranchised from freely exchanging information.”

Internet Society board of trustees member Glenn Ricart, a former program manager at DARPA now with Price Waterhouse Coopers, predicts a mix of system regulation. “A few nations (or cities) may choose to make smooth, low-cost, ubiquitous communications part of their national industrial and social infrastructure (like electrical power and roads),” he predicted. “Others (and I’d include the United States here) will opt for an oligopoly of providers that allows for limited alternatives while concentrating political and economic power. Individuals and businesses will provide local enclaves of high quality connectivity for themselves and their guests. A somewhat higher-cost ‘anywhere’ (e.g. cellular) infrastructure will be available where governments or planned communities don’t already include it as an amenity. I believe that the Internet will not be uniform in capability or quality of service in 2020: there will be different tiers of service with differentiated services and pricing.”

Stewart Alsop, writer, investor and analyst, commented that there’s a chance for innovations to make a world-changing difference in the next 15 years. “This depends on technology standards exceeding the self-interest of proprietary network owners, like mobile operators, cable and telephony network owners, and so forth,” he explained. “So timing is still open, but most likely by 2020.”

There is also a theme in some answers that focuses on the technical complications of making big systems work together. This is what Mikkel Holm Sorensen, a software engineer and intelligence manager at Actics Ltd., argued: “Patching, tinkered ad hoc solutions, regional/national/brand interests and simple human egoism in general is the order of technology and design. This will never change, unless suppressed by some kind of political regime that takes control in order to harmonize technology, protocols and formats by brute force. Does anybody want that in order to attain compatibility and smooth operation (even if possible)? No, of course not.”

A notable group says it will continue to be difficult to bridge digital divides.

Another issue raised by respondents was the difficulty involved in bringing technology to remote regions and to people living in the poorest conditions. Craig Partridge, internet pioneer and chief scientist at BBN Technologies, wrote: “We tend to overestimate how fast technology gets installed, especially in third-world countries. One is tempted to say yes to this idea, given the tremendous profusion of cellular over the past 20 years or so. But it is far too optimistic. If one limited this to first- and second-world countries, the answer would be more clearly ‘yes it will happen.’“

The Internet Society’s Fred Baker’s answer included a similar point. He wrote: “Mobile wireless communications will be very widely available, but ‘extremely low cost’ makes economic assumptions about the back sides of mountains in Afghanistan and the behavior of entrepreneurs in Africa.”

Adrian Schofield, head of research for ForgeAhead, an information and communications consulting firm, and a leader with Information Industry of South Africa and the World Information Technology and Services Alliance, pointed out the fact that there may always be people left behind. “Although available,” he wrote, “not everyone will be connected to the network, thus continuing the divide between the ‘have’ and ‘have not.’“

And Matthew Allen, president of the Association of Internet Researchers and associate professor of internet studies at Curtin University in Australia, echoed many respondents’ sentiments when he wrote: “Fundamental development issues (health, education, basic amenities) will restrict the capacity of many people to access networks.” Alejandro Pisanty – CIO of the National University of Mexico, a member of the Internet Governance Forum Advisory Group, and a member of ICANN’s board of directors – boiled it down to numbers. “At least 30% of the world’s population will continue to have no or extremely scarce/difficult access due to scarcity of close-by services and lack of know-how to exploit the connectivity available,” he predicted. “Where there is a network, it will indeed be of moderate or low cost and operate smoothly. Security, in contrast, will continue to be a concern at least at ‘Layer-8’ level.”

Jonathan Zittrain, the first holder of the chair in internet governance and regulation at Oxford University, an expert on worldwide access and co-founder and director of Harvard University’s Berkman Center for the Internet and Society, also boiled it down to numbers. “’Anywhere on the globe to anyone’ is a tall order,” he responded. “I think more likely 80% of the bandwidth will be with 20% of the population.”

Author, teacher and social commentator Douglas Rushkoff summed up the opinions of many respondents regarding the proposed operating environment scenario for 2020 when he wrote: “Real interoperability will be contingent on replacing our bias for competition with one for collaboration. Until then, economics do not permit universal networking capability.”

And Marilyn Cade of the Information Technology Association of America and the Generic Names Supporting Organization of ICANN, expressed a common theme when she wrote, “I wish this [optimistic scenario] were TRUE. And I want it to be true, and I want all of us to work very hard to make it as true as possible! First of all, we are at 2006, and we need to address connectivity and affordable access still for vast numbers of potential users on the planet Earth.”

In responding to this survey’s optimistic 2020 operating system and access scenario, foresight expert Paul Saffo, director of the Institute for the Future, wrote: “My forecast is that we will see neither nirvana nor meltdown, but we will do a nice job of muddling through. In the end, the network will advance dramatically with breathtaking effect on our lives, but we won’t notice because our expectations will rise even faster.”

Here is the current state of play in the network’s global development.

The continued innovation of the architecture of the internet to support the flow of more data efficiently and securely to more people is no small order, but it is a given in most technology circles. The most-often-mentioned hurdles to a low-cost system with access for all are not technological. The survey respondents nearly unanimously say the development of a worldwide network with easy access, smooth data flow, and availability everywhere at a low cost depends upon the appropriate balance of political and economic support.

The battle over political and economic control of the internet is evident in the loud debate in the U.S. Congress in the spring and summer of 2006 over “network neutrality” (with internet-dependent companies such as Microsoft and Google facing off against the major telecommunications corporations such as AT&T that provide the data pipelines) and in the appearance of a newly formed world organization that grew out of the UN’s World Summit on the Information Society – the Internet Governance Forum (www.intgovforum.org), which will meet for the first time in October 2006.

The technology to make the internet easy to use continues to evolve. World Wide Web innovator Tim Berners-Lee and other internet engineers in the World Wide Web Consortium are working on building the “semantic Web,” which they expect will enable users worldwide to find data in a more naturally intuitive manner. But at the group’s May WWW2006 conference in Edinburgh, Berners-Lee also took the time to campaign against U.S. proposals to change to an internet system in which data from companies or institutions that can pay more are given priority over those that can’t or won’t. He warned this would move the network into “a dark period,” saying, “Anyone that tries to chop it into two will find that their piece looks very boring … I think it is one and will remain as one.”7

The problem of defeating the digital divide has captivated many key internet stakeholders for years, and their efforts continue. Nicholas Negroponte of MIT’s Media Lab has been working more than a decade to bring to life the optimistic predictions he made about an easily accessible global information network in his 1995 book “Being Digital.” He hopes to launch his “one laptop per child” project (www.laptop.org) in developing nations later in 2006 or in early 2007, shipping 5 to 10 million $135 computers to China, India, Thailand, Egypt and the Middle East, Nigeria, Brazil and Argentina. Partners on the project include the UN, Nortel, Red Hat, AMD, Marvell, Brightstar and Google. The computers will be equipped with Wi-Fi and be able to hook up to the internet through a cell phone connection. The developers hope to see the price of the computers drop to $100 by 2008 and as low as $50 per unit in 2010. “We’re going to be below 2 watts [of total power consumption]. That’s very important because 35% of world doesn’t have electricity,” Negroponte said. “Power is such a big deal that you’re going to hear every company boasting about power” in the near future. “That is the currency of tomorrow.”