Introduction

Tens of millions of Americans turn to the Internet when they need help with health problems. Health professionals are often apprehensive about the reliability of online health information and wonder how consumers can possibly find good advice in the untamed wilderness of the Internet. In an environment where any quack can create a credible-looking Web site and promote all manner of questionable “cures,” how can Internet users know what information will most benefit them? What signals of quality should they seek?

Some experts warn about another danger – that the best information is not even on the Internet. An exhaustive study by the California HealthCare Foundation and RAND Health found “substantial gaps in the availability of key information” relating to breast cancer, depression, obesity, and childhood asthma available through English- and Spanish-language search engines and Web sites.15 Another study, funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, echoed RAND’s cautionary tone after comparing the 25 most popular health Web sites’ adherences to quality codes, peer review, and external advisory boards.16 And the American Medical Association (AMA) has taken the position that online health information is never a substitute for a physician’s experience and training, suggesting that Americans make a new year’s resolution to “trust your physician, not a chat room.”17

Widespread skepticism among medical providers has not deterred the remarkable growth in the number of people seeking medical information online. More Americans research health information online on an average day than visit health professionals. About 6 million Americans go online for medical advice on a typical day, whereas the American Medical Association estimates that there are an average of 2.75 million ambulatory care visits to hospital outpatient and emergency departments per day and an average of 2.27 million physician office visits per day. So we set out to examine how Internet users search for information, how they establish its credibility, and how they decide to act on it. We used several approaches. We surveyed 500 Internet users who go online for health care information. This special sample, surveyed June 19-August 6, 2001, portrays the overall habits and attitudes of those Americans who use the Internet for medical information and advice. We also gained insights from two online focus groups conducted on October 15, 2001, by Harris Interactive. In one group, six participants with special needs discussed how they use the Internet to manage their chronic illnesses and care for their loved ones. In the second group, ten participants representing the general population discussed how they use the Internet to take better care of themselves and their loved ones.

Part One: A basic profile of health seekers

Who is searching for health information online?

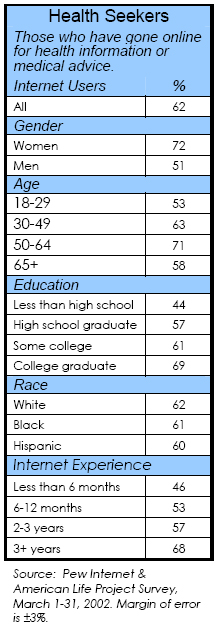

In a national survey conducted March 1-31, 2002, the Pew Internet Project found that 62% of Internet users, or 73 million people in the United States, have gone online in search of health information. Women are more likely than men to have researched a medical question online. Some 72% of online women have sought medical information online, compared with 51% of online men. Those in the middle age groups are more likely to turn to the Internet for health information than those under 30 or over 65. College-educated Internet users are more likely to search for medical advice online than those with a high school education. Longtime users are more likely than Internet newcomers to look online for health tips. Interest in health information cuts across ethnic and racial groups in a relatively equal way – white, black, and Hispanic Internet users are equally enthusiastic for such material.

Fifty-seven percent of health seekers describe themselves as in “good” health. Twenty-nine percent of health seekers say they are in “excellent” health and 14% say they are in “fair” or “poor” health. By comparison, the National Center for Health Statistics reports that 37% of Americans assess their health as “excellent,” 31% say it is “very good,” 23% say it is “good,” and 9% say their health is “fair” or “poor.”18 Not surprisingly, those in fair or poor health search for medical advice more frequently and on more topics than those in better health.

On a typical day, 5% of all Internet users – about 6 million Americans – go online to look for health information. There are few differences in the population of Internet users who searched online “yesterday”; men, women, old, young – all were equally likely to look for medical advice. However, it seems that those with more online savvy may be more accustomed to answering a health question online – 7% of Internet users with three or more years of experience search on a typical day, compared with 2% of Internet users with just six months of experience online.

Part Two: Hot topics

Weight control and prescription drug information are high on the list of health interests

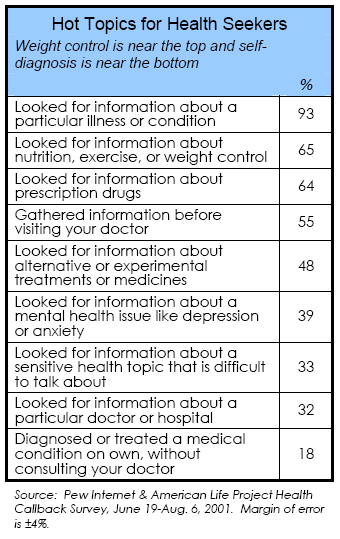

Almost every health seeker (93%) has looked at one time or another for information about a particular illness or condition. Roughly two thirds of all health seekers have looked for information about nutrition, exercise, or weight control. In our August 2000 survey, 13% of health seekers said they had sought information about just “fitness and nutrition.” The new survey shows a big increase when weight control is added to this list. Those who describe their health as “fair or poor” are more likely than those in excellent health to have looked for information about nutrition, exercise, or weight control.

Two thirds of all health seekers (64%) have looked for information about prescription drugs. Those who have seen a doctor in the past year are more likely to use the Internet to research a certain drug than those who have not consulted with a doctor. In our August 2000 survey, only 10% of health seekers said they had purchased medicine or vitamins online. As with other aspects of online shopping, there are more browsers than buyers. Part of the reason for this is that many people prefer to make their actual purchase in stores. Others are worried about the security of their credit card information. Nonetheless, the Web is increasingly important to “window shoppers” – those gathering consumer information, doing price comparisons, checking out alternative purchases.

More than half of all health seekers have gathered information before visiting a doctor. Health seekers dealing with a chronic disease or disability are more likely to do their homework before a doctor’s appointment. One member of the Harris Online focus group living with fibromyalgia said, “I can at least go into the doctor’s office with a good knowledge of what is going on and ways of treatment.”

Nearly half of all health seekers (48%) have looked for alternative or experimental treatments or medicines. Those who have been treated for a serious illness in the past year are more likely to have done this – 62%, compared with 48% of those who have escaped such a diagnosis. One focus group participant who is living with a chronic condition said, “I hope to find new ways to treat myself without using medication.” Another chronically ill participant agreed, saying, “Most doctors are not up to date on alternative methods.”

Thirty-nine percent of health seekers have looked for information about a mental health issue such as depression or anxiety. Those who have visited an emergency room for medical treatment in the past year are more likely to have looked for mental health information online – 49%, compared with 37% of health seekers who have not been to the emergency room. In August 2000, 26% of health seekers said they had ever looked for this type of information. Although our survey ended August 6, 2001, this increased interest in mental health information probably accelerated in the wake of the September 11 terrorist attacks. As an indication of this, Michelle Pruett, media director for the National Mental Health Association, says the association’s Web traffic increased by 50% from September to October and the top destination was “Coping with Disaster,” an information page for helping children deal with disaster-related anxiety.

Similarly, 33% of health seekers have looked for information about a sensitive health topic that is difficult to talk about, which is a big jump from the 16% of health seekers who said they had done this in August 2000. Men are more likely than women to have done this – 38% of male health seekers, compared with 29% of female health seekers.

Frequent health seekers are more likely than occasional seekers to have tried every activity we asked about, from looking for weight control tips to diagnosing a medical condition on their own. For example, 74% of health seekers who go online at least several times a month have looked for information about nutrition, exercise, or weight control. Fifty-nine percent of Internet users who go online every few months or less have done this. Not surprisingly, health seekers who say the Internet has improved the way they take care of themselves are also more likely to have gone down all sorts of avenues in pursuit of medical advice – and to have found the right information the last time they did a search.

Part Three: Search strategies

Most go it alone

To get a picture of Internet users’ actual behavior, we asked health seekers to relate details about their most recent information search. Most health seekers (86%) just plunged right in to see what they could find rather than asking anyone for advice about which Web sites to use. Of the 14% of health seekers who asked someone for advice, most followed that counsel at least a little bit. However, 41% of health seekers who got advice said they ended up finding the information they wanted on their own.

Most use a search engine and visit a few sites

In keeping with other research into health seekers’ habits,19 we found that the vast majority (86%) visit multiple sites when looking for health information and do not have one favorite site. Most start at a general, non-specialty Web site – a search engine or a portal. They surf to other sites after finding information or links to them on the general site. The typical range of sites visited is two to five. Eighty-nine percent of health seekers who visit multiple sites say that, in general, they start at a site like Yahoo or the AOL home page. Just 8% of health seekers who visit multiple sites say they are most likely to start at a specialized health site like WebMD.com.

Last time they searched for health advice, those who used a search query on a search engine were more focused on getting the information fast than finding a trusted name – 45% started at the top of the search results and worked their way down; 39% read the results list and then clicked on the items that seemed to be the most relevant; and just 12% clicked on a site because they recognized the sponsor or name.

A small number consult one favorite site

About one in three health seekers (29%) has bookmarked health-related Web sites or saved them as a “favorite place” for consultation again and again. Frequent and enthusiastic health seekers are more likely to have health-related bookmarks, as are those who saw a doctor in the past year.

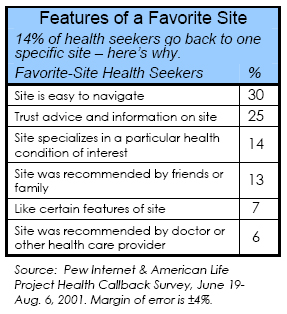

When asked if they have one favorite site, 14% of health seekers said yes. Of that small group, 35% named WebMD. Other sites named by these “favorite-site” health seekers include the Mayo Clinic site, the National Institutes of Health, InteliHealth, Medline, and DrKoop.com. One online focus group participant who is a fan of WebMD commented, “I know it so well it is just easier to go to it every time I have a question.”

About one quarter of health seekers with one favorite site say they first went to it because of a personal recommendation, usually from a friend or family member, and a small number got the tip from a doctor or other health professional. Another quarter of favorite-site health seekers saw an advertisement for the site. The third quarter found it through an Internet search, and another 12% just came across their favorite site while surfing the Web. One focus group participant said that he ended up getting good advice from health chat rooms recommended by “close friends who thought they would help.”

Health seekers with a favorite site are often rewarded for their focused approach. Of the 41% of health seekers who went to a specialized health site or health portal site the last time they went online for health information, about half (53%) said the site delivered exactly what they needed. Thirty-seven percent of these focused health searchers went on to other sites.

For some health seekers, the need for detailed, specialized information is vitally important. One focus group participant who is living with 18% lung capacity put it this way: “Most commercial sites have the basics of an illness. I am beyond basics.”

Most are occasional users

Most health seekers are only occasional visitors to health and medical sites. Fifty-eight percent of health seekers use the Internet to look for medical advice or health information every few months or less. Forty-two percent of health seekers search for health information at least several times a month – 4% do so every day, 13% search several times a week, and 25% search several times a month. Those in excellent health are less likely to haunt health Web sites than those who describe their health as good, fair, or poor.

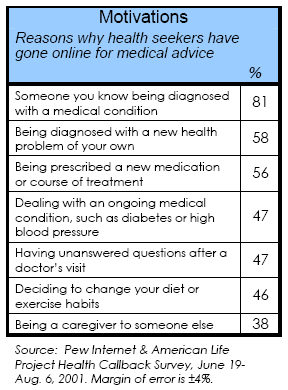

Many are looking on behalf of someone else

Worrying about someone else’s health issue is the No. 1 motivation for health seekers to go online for medical advice, whether for a friend, spouse, child, or parent. Eighty-one percent of health seekers have gone online because someone they know was diagnosed with a medical condition. In addition, 38% of health seekers have gone online because they are caring for someone else. Indeed, when asked about their last online health search, half of health seekers say they were looking on behalf of someone else. (See the separate section on caregivers, Page 29.)

New symptoms spur research for individuals

Fifty-eight percent of health seekers have gone online because they themselves were diagnosed with a new health problem. Other important motivating factors include being prescribed a new medication or treatment; dealing with an ongoing condition; having unanswered questions after a doctor’s visit; and deciding to change diet or exercise habits.

The middle age groups (30-49 years old) are more likely than young health seekers or senior health seekers to be motivated to go online for all these reasons, except one. Older health seekers are more likely to go online for information about how to deal with an ongoing medical condition, such as diabetes or high blood pressure. Not surprisingly, those in less-than-excellent health are more likely to go online to research a new diagnosis or medication. There are few differences, however, when it comes to feeling underserved by a health professional – no single group is more motivated than another to go online because they had unanswered questions after a doctor’s visit.

Searching from home to answer a specific question

The great majority of health seekers went online from home the last time they searched – 80% of health seekers. Just 16% of health seekers went online from work the last time and 4% said they went online from somewhere else, such as a library or a friend’s house. As one at-home mother said in an online focus group, “If I did work, I would probably be too embarrassed to look up stuff online.” Another focus group participant echoed her concern, saying, “I know we monitor the use of the Net at work and I have seen it work against people.”

The last time they went online for health information, 62% of health seekers researched a specific illness or condition. When we asked what illness or condition they searched for, 12% of this subgroup of disease-researching health seekers said they were researching cancer. Other commonly named illnesses included diabetes, heart condition, arthritis, mental health, and conditions affecting the skin, kidneys, lungs, the brain, and bone density. The rest of those who looked for information on a specific illness revealed a wide range of concerns, from spider bites to autism.

Health seekers with one illness in mind were quite focused the last time they went online for information. They tended to be looking for information about medications or treatments for that particular illness, for details about the symptoms of that illness, and for the disease’s prognosis.

The last time they went online for health information, 14% of health seekers sought information about specific doctors, hospitals or medicines. This is a notable increase from our August 2000 survey, which found that 9% of health seekers had searched for a specific doctor the last time.

Fourteen percent of health seekers sought information about fitness, nutrition, or general wellness the last time they went online for health information. Ten percent of health seekers sought information about a specific surgical or diagnostic procedure. Ten percent of health seekers went looking for basic health care news.

Part Four: Evaluating the quality of health information

The recommended way to assess medical material

A substantial majority of health seekers do not follow the verification protocols recommended by experts such as the Medical Library Association when searching for information. The MLA recommends that searchers identify each site’s sponsor, check the date of the information posted, and verify that the material is factual information, not opinion. The California HealthCare Foundation recommends that consumers take ample time to search for health advice, visit four to six sites, and discuss the information with a health care provider before making a treatment decision. Advocates for privacy, such as the Center for Democracy and Technology, recommend reading a site’s privacy policy very carefully – and writing a protest email to any site that doesn’t post a policy.

In fact, most health seekers go online without a fixed destination in mind. The typical health seeker starts at a search site, not a medical site, and visits two to five sites. She feels reassured by advice that matches what she already knew about a condition and by statements that are repeated at more than one site. She is likely to turn away from sites that seem to be selling something or don’t clearly identify the source of the information. And about one third of health seekers who find relevant information online bring it to their doctor for a final quality check.

Respondents seemed to fall into three groups – about a quarter of them are vigilant about verifying a site’s information, another quarter are concerned but follow a more casual protocol, and about half mostly avoid the kind of search strategies experts recommend. And although health seekers are generally wary about revealing their identity online or having their activities tracked, only about one in five have checked a site’s privacy policy.

Health seekers’ basic presumptions

Health seekers generally start their searches in a confident frame of mind – and this might be the reason that so many avoid digging into the background of the information they are retrieving. Fully 72% of health seekers say you can believe all or most of the health information online. Part of the reason for their upbeat assessment might stem from the fact that 69% of health seekers say they have not seen any wrong or misleading health info on the Web – although 28% of health seekers have seen bad information. It should be noted that consumers’ radar is not as highly tuned as a health professional’s – consumers may not be aware of what is not readily found on the Web. It also could be the case that health seekers are so pleased with the convenience of getting health information online that they forgive any shortcomings of online medical advice. In our August 2000 survey, 93% of health seekers said it is important that they can get health information when it is convenient for them. One focus group participant said the Internet makes it “so easy to look up things” and “go deeper into the problem” that she frequently uses it to check her doctor’s diagnosis or her mother’s advice.

If it fits with what they’ve already heard, they believe it

In most cases, health seekers decide to believe what they read online because it fits with the facts they already know. Nine out of ten health seekers who found the information they were looking for the last time they searched said the health information mostly agreed with what they already thought or knew. Only 4% of successful searchers said the information mostly disagreed with what they knew, and 7% of successful searchers said they found information that both agreed and disagreed with what they knew. In an online focus group, one participant said, “When I had surgery I found a lot of information that corresponded with what the doctor had told me. It made me feel more at ease.” Another participant living with a chronic disease explained why he continues to read and re-read online health information, saying, “I want to read everything I can locate regarding my disease on any site I locate. [It] is mostly rehashing but [I] often find a new tidbit or two.”

At the same time as they are relying on online information that confirms what they already believe, most health seekers also pick up new insights about medical conditions or treatments when they do their searches. Eight out of ten successful searchers said they learned something new the last time they went online for health information.

When they read the same facts at different sites, health seekers’ trust in those sites grows

If a site confirms what they already know or they found similar information on multiple sites, health seekers were more confident in those sites. Of the health seekers who visited two or more sites during their last search and found what they were looking for, two thirds (67%) say the multiple sites provided mostly the same information. A majority of multiple-site searchers who found similar information on different sites say the similarities gave them more confidence in the sites – 49% say it gave them a lot more confidence, 38% say it gave them a little more confidence. Eleven percent of multiple-site searchers who saw similar information say it did not give them more confidence.

A participant in an online focus group said that he trusts information more if he sees it on more than one site, saying, “There is a lot of bogus info out there but at least it is a starting point.” Another participant said, “On the Internet you can get four or fifty different opinions and if they are all the same advice your doctor gave you, you can relax and not wonder if he was right or if his info is dated.”

It is important to note that some health-related content is syndicated and may appear on multiple sites. Consumers may think they have verified a piece of information by reading two sources, but in fact may have simply re-read the same material from the same syndicate at two different Web sites. For example, Well-Connected reports about common diseases and wellness issues have appeared on WebMD, CBS HealthWatch, MDConsult.com, and Discovery Health.20

One third of multiple-site searchers (30%) say the different Web sites they visited provided different information. The fact that they found different information at different places had a smaller effect on health seekers than the similarity of information had on searchers. One fourth of multiple-site searchers who had found differing opinions say the differences gave them less confidence in the Web sites – 6% say it gave them a lot less confidence and 17% say it gave them a little less confidence. Three-quarters of these multiple-site searchers (76%) say it did not give them less confidence in the sites. Perhaps this reflects recognition by health seekers that there is often not uniform advice from the medical establishment about how to treat some medical conditions.

Health seekers’ information assessment screens

Other researchers have spelled out the factors that potentially affect a user’s decision to visit a certain Web site. For example, the Utilization Review Accreditation Commission (URAC), a nonprofit accreditation organization, asked health seekers to rate the importance of various features to be found on health Web sites. Its survey found that a “seal of approval,” links to related sites, interactive tools, and a list of sponsors would increase consumer trust in a health Web site.21 In a more general survey conducted for Consumer WebWatch, 80% of Internet users said it is “very important” that a site is easy to navigate. Just 19% of Internet users said that a seal of approval is “very important” when it comes to deciding whether to visit a site.22

Since many surveys have asked questions in the abstract (“Which of the following do you think is the most important attribute for a health related Web site to have?”), we decided to ask health seekers to describe steps they had actually taken to check facts or reject a Web site’s advice.

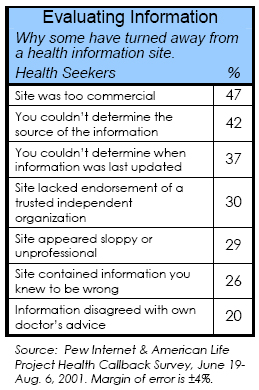

When users are asked about the reasons they have rejected information from a health Web site, many report that they have taken the expert advice to heart. They turn away from sites that do not identify the source or date of the information. But they add a few tests of their own. E-patients say that overt commercialism is the No. 1 reason they have turned away from a site. Forty-seven percent of health seekers have decided not to use information they found because the Web site was too commercial and seemed more concerned with selling products than providing accurate information.

In the Harris Online focus group, health seekers were asked what factors make them feel a particular resource is not trustworthy. An overabundance of advertising, particularly “pop-up” ads, made a few participants’ lists of negative factors. One woman took a hard line and said, “If a site has a shopping cart I don’t go back.”

Health seekers also pay attention to what many experts believe is one of the most important factors in judging the quality of online health information – they look for the source23 Forty-two percent of health seekers have turned away from online information because they couldn’t determine the source or author of the information. Not every e-patient looks for the source every time she goes online, however. When asked if they check the source, 58% of health seekers who go to multiple health Web sites say they do so “most of the time” or “always.” Fifty-five percent of health seekers who consult one favorite site say they have checked the source of the information on that site. When thinking about what would make him trust a site, one focus group participant said he looks for the name of “a reputable doctor that I have seen on television or who has printed articles in notable journals.”

Men are more likely than women to blame a site’s sloppy or unprofessional design as the reason for turning away from the information. Younger health seekers are also more influenced by the site’s design than older users. Otherwise, there were no notable differences among demographic groups for the other information quality signals.

Commercialization and search engines

Overt commercialism erodes the credibility of health sites, but what about subtler influences? Consumer WebWatch, a project partly funded by the Pew Charitable Trusts, found that only 39% of Internet users knew that some search engines are paid to list some sites more prominently than others. When told about the practice, 80% of Internet users said it was important for search engines to disclose these arrangements. But only 30% of Internet users said they are less likely to use a search engine that accepts money to promote certain sites and fully 56% of Internet users said it makes no difference to them.24

A typology of health seekers

- Vigilant health seekers

About one quarter of health seekers say they always check the source, date, and privacy policy on a health Web site. These Vigilant health seekers are more likely than other types of health seekers to say the Internet has improved the way they take care of their health – 72%, compared with 63% of Concerned health seekers and 54% of Unconcerned health seekers. This group seems to approach the search for health information quite methodically, trusting search engines to some degree, but clicking on a recognized name more often than the other two groups. Vigilant health seekers are more likely to take their time and visit many sites during a typical search. Seventy percent of Vigilant health seekers spent more than half an hour online during their last foray, compared with 52% of Unconcerned health seekers who devoted that much time. Thirty-one percent of Vigilant health seekers went to four or five sites the last time, compared with 16% of Unconcerned health seekers who did the same. Vigilant health seekers are by far the most likely to talk to a health care professional about what they found online – 51% of Vigilant health seekers did so the last time they searched for health information, compared with 25% of Unconcerned health seekers.

- Concerned health seekers

Another one quarter of health seekers say they check the source, date, and privacy policy of a health Web site “most of the time.” This group seems to trust the search engines to return good results more than the other two groups. Concerned health seekers are the most likely to start at the top of the search results list instead of reading the explanations or looking for a trusted name.

Concerned health seekers are as likely as Vigilant health seekers to go online because they are dealing with an ongoing medical condition. Concerned and Vigilant health seekers are also equally likely to have turned away from a health site because they could not determine the source or author of the information.

- Unconcerned health seekers

About half of all health seekers say they check the source, date, and privacy policy of a health Web site “only sometimes,” “hardly ever,” or “never.” They are the least likely to say the Internet has improved the way they take care of their health. Unconcerned health seekers are the least likely group to be living with a chronic illness like diabetes or high blood pressure. Unconcerned health seekers are, not surprisingly, the least likely to have turned away from a health site because they could not determine the source or author of the information – 31%, compared with 52% of Vigilant health seekers. Unconcerned health seekers seem to be in a hurry – they are more likely than the other groups to visit between one and three sites and to spend less than half an hour on a typical search for health information. Unconcerned health seekers are also the least likely to talk to a medical professional about what they found online.

Health seekers still rely on doctors for guidance and fact-checking

A small minority of health seekers is going online instead of seeing a doctor. Fourteen percent of health seekers say they’ve gone online because they didn’t have time to see a doctor. Eight percent say they have gone online because they couldn’t get a referral or an appointment with a specialist. Asked in a different way, a total of 18% of health seekers say they have gone online to diagnose or treat a medical condition on their own, without consulting their doctor. Those who have been treated for a serious illness in the past year are more likely to use the Internet to self-diagnose, as are those who have gone to the doctor at least once in the past year, so these are not necessarily people who reject a doctor’s advice altogether. They are supplementing their care with advice gleaned from the Internet. For example, one focus group participant who is living with a chronic illness said that he finds health Web sites “help clarify some of the things I don’t quite understand” after a doctor’s appointment.

However, another participant in an online focus group lauded the Internet’s ability to help him avoid the doctor’s office: “When I get sick, I know what to do to get rid of the cold without going to the doctor.” Another said, “I don’t see a doctor unless I am really sick. If I have any questions I check out Internet sites.”

After their most recent health search, more than one third of successful searchers (37%) talked to a doctor or other health care professional about the information they found online. Two thirds of successful searchers (63%) said they did not talk to a health care professional about what they found – mostly because the health seeker deemed the topic too insignificant to seek expert advice. This finding is consistent with an August 2000 Pew Internet Project survey and may reflect consumers’ confidence in their decision-making abilities rather than a fear of rejection by their doctor or their rebellion against a doctor. Just 2% of those who did not talk to a doctor say it was because they didn’t think their doctor would listen.

Indeed, health professionals seem to be receptive to those consumers who bring in the information they find online. Thirty-one percent of those who talked to their doctor say he was “very interested” and 48% say their doctor was “somewhat interested” in the information found online. Just 13% of successful searchers who chose to talk to their doctor got the cold shoulder and report that the health care professional was “not too interested” or “not at all interested.” Despite the American Medical Association’s cautions to consumers against online information25, a 2001 Harris Interactive poll26 found that doctors are using the Internet to increase their medical knowledge and improve the care they provide to patients. It is therefore not surprising to hear that more and more doctors are receptive to patients going online to gather more information.

When we asked focus group participants about their relationships with their doctors, most confirmed the positive trend toward receptive doctors. One participant said he talks to his doctor about what he finds online because “sometimes I just need his reassurance I interpreted my info correctly.” However, another participant had a different experience when she brought in Web printouts, relating that her doctor “got mad, like I didn’t trust him. Actually, I didn’t. So I changed doctors.”

Health care professionals also were likely to agree with the information a successful searcher found online. Eighty-two percent of health seekers who discussed what they found with a health care professional said the doctor or nurse agreed with the information.

Health seekers who say the Internet has improved the way they take care of their health are more likely to talk with a doctor about what they found online. Forty percent of these enthusiastic health seekers did so, compared with 30% of those who are less keen on Internet health information.

Of the 63% of successful searchers who did not talk to a health care professional about what they found, 43% say the topic wasn’t a health issue that required a visit or phone call with a doctor. Seventeen percent say they had done the research on someone else’s behalf and therefore did not discuss it with a health professional. Twelve percent say they didn’t think the information was worth mentioning. Eight percent say they were checking on their doctor’s diagnosis, so they already had his or her opinion on the topic. For example, one participant in an online focus group said she usually goes to see her doctor when she’s not feeling well and then goes online “to see if he is on track with his information.”

Seven percent of successful searchers who did not talk to a health care professional about what they found say they haven’t had time to see the doctor about it yet. Small numbers of health seekers say they forgot to bring it up, thought the doctor wouldn’t listen, or say it was too difficult to talk about with a health care professional.

Part Five: Results

Successful searches

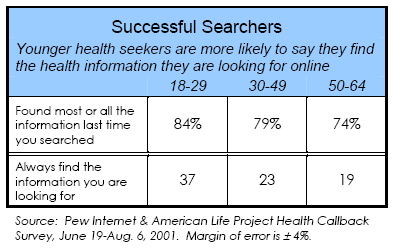

Eight in ten health seekers found most or all of the information they looked for online the last time they searched. Fourteen percent of health seekers say they just ran out of time and had to stop looking, whether or not they had all the answers they needed. A very small minority of health seekers (6%) said they couldn’t find the information they were looking for and gave up.

Age is a factor associated with successful searching. The youngest health seekers (18-29 years old) are more likely to say they “always” find the information they are looking for online. Younger users are no more likely to have found one favorite site or other stratagem – they were easier to please, more confident of their search skills, or both.

Health seekers who are living with a chronic disease or disability are most likely to say they gave up before finding the right information, possibly because they are looking for more detailed or rarer kinds of material. Success did not depend on whether the health seeker has one favorite site or visits many different sites – the vast majority of both groups found what they were looking for.

Health sites please users more than they please health care professionals. The results of the California HealthCare Foundation/RAND study demonstrated those concerns: “Only half of the topics that the expert panels thought were important for consumers were covered more than minimally.”27 In addition, they found that most of the content was written at a high school or college reading level – much higher than the sixth-grade reading level recommended by experts concerned about consumers’ ability to understand the information. However, some of our respondents suggested that high-level writing may inspire trust in the site. One participant in our online focus group said, “When I can only half understand what they’re saying, I start to feel they’re competent.”

The vast majority of health seekers who found the information they were looking for said it was easy to find – 61% said it was “very easy” and 33% said it was “somewhat easy.”

The California HealthCare Foundation/RAND study recommends spending at least 30 minutes on a search to be sure a health seeker has delved deeply into a topic. During a typical search, most health seekers exceed the recommended time allowance. The last time they went online for health information, 12% of health seekers spent less than 15 minutes and 27% spent between 15 and 30 minutes. Thirty-five percent of health seekers spent between a half hour and an hour online. Nineteen percent of health seekers spent one to two hours online and 7% spent more than 2 hours online the last time.

The last time they went online for health information, 51% of successful searchers said they found the information they needed on a site they were already familiar with or had used in the past. Forty-four percent of successful searchers said they found the information on a site they had never heard of before. Three percent of successful searchers said they had found the information on both familiar and unfamiliar sites.

Those in excellent health are more likely to have chanced upon relevant health information – probably because they do not need to search very frequently and are less familiar with health sites. Those in less-than-excellent health are more likely to have visited a familiar site and found what they needed, as are people who search for health information more frequently.

Part Six: Impact

In a survey in January 2002, we asked Internet users whether they themselves had dealt with an illness in the past two years. Seventeen percent said yes, and about one in four of those Internet users say the Internet played a key role in the way they took care of themselves. Women were twice as likely as men to report that their use of the Internet played an important or crucial role in their coping with sickness. And those aged 50-64 were more likely than other age groups to report a significant impact from their use of the Internet.

In our special survey of health seekers, 61% of respondents say the Internet has improved the way they take care of their health either “a lot” or “some.” This is a significant increase from an August 2000 Pew Internet Project poll that found that 48% of health seekers said the Internet improved the way they take care of themselves. Indeed, about 45 million Americans now say the Internet has improved the way they take care of their health, compared with 25 million Americans who said that in August 2000.

Health information’s impact

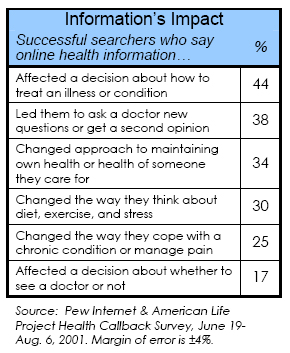

Health seekers are mostly going online to look for specific answers to targeted questions. Often, this information helps them make informed decisions, but it rarely induces them to make a wholesale change in their approach to health care.

Most of those who have completed successful searches report that the impact of those searches was modest. Of the health seekers who found the information they needed the last time they went online for medical advice, 16% say the information had a major impact on their own health care routine or the way they care for someone else; 52% say the information had a minor impact; 31% say it had no impact at all. The impact was equally felt among all groups – old, young, men, women, college-educated or not.

Those who searched on behalf of a loved one were as likely to say the information had an impact as those who searched for answers to their own health questions.

In an online focus group, one participant said online information helped identify a major neck problem that a doctor later confirmed. Yet another participant said she turned to the Internet after a “painful joint replacement in my foot. I [then] knew about the recovery period and what I could or could not do.”

Of the successful searchers, 44% said the information they found online affected a decision about how to treat an illness or cope with a medical condition. Again, there was no significant difference between those who searched on behalf of someone else and those who searched on behalf of themselves. The only topics that prompted dramatically different answers from these two groups were diet, exercise, and stress. Forty-one percent of health seekers looking for information for themselves say they changed the way they think about diet, exercise, and stress based on what they found online. Just 20% of health seekers looking on behalf of someone else felt the same way.

About one in three health seekers know someone who has been significantly helped by following medical advice or health information they found on the Internet. Fittingly, those most in need are most likely to reap the benefits of online health information. Fully 51% of those who have been treated for a serious illness in the past year say they or someone they know was significantly helped by following advice they found on the Internet.

In an online focus group, one woman said, “When I was pregnant, [online health information] eased my worries, making it an easier and less stressful pregnancy.” Based on what she read online about the risks and trade-offs of prenatal testing, this health seeker decided not to go through with amniocentesis to find out if the baby had Down’s syndrome.

Another focus group participant, who is living with a chronic condition, found that online research improved her quality of life in ways that her doctor deemed too insignificant to mention. “My hair fell out in gobs for years,” she said. “I found out on the Web that the medication I was on did that. Only then did [my doctor] say yes, he knew it could do that. I had told him previously about the hair loss.” This focus group participant was unhappy that her doctor had omitted key information from their conversations, but she was grateful to members of her online support group who posted the truth.

Just 2% of health seekers know someone who has been seriously harmed by following medical advice or health information they found on the Internet. While this small number may cheer advocates of online health information, it serves as a warning for e-patients who may rely too heavily on the advice they find on the Web. For example, in a case reported in the March 2002 issue of Pediatrics, a one-year-old boy suffering from diarrhea was brought to an emergency room. A clinician incorrectly advised his parents to stop giving him solid foods, but to provide fluids for rehydration. The parents independently searched online and found similar advice on an unidentified Web site, so they continued the treatment recommended at the hospital. Over the next few days, the child become increasingly weak and eventually was admitted to the hospital, where he recovered.28 Of course, it was a medical professional who made the first mistake, but the inaccuracy on the Web site exacerbated the problem.

Part Seven: Email, support groups, and personalization

Few go beyond Web searching

Most health seekers stuck to Web searching the last time they went online for health information, but 3% communicated online with a health care professional, such as a doctor or nurse. Another 3% communicated with a Webmaster of a particular health Web site, while yet another 3% communicated with members of an online support group at some point in their last online search.

These small numbers are consistent with an August 2000 Pew Internet Project survey which found that 9% of health seekers said they had ever used email or gone to a Web site to communicate with a doctor or a doctor’s office. However, when asked if they would like to communicate with their doctor online, health seekers in an online focus group were very receptive – as long as the doctor actually replied in a timely manner. As one man who does exchange email with his doctor said, “It is faster to call.” A 2002 Harris Interactive poll found that 90% of Internet users would like to email their doctor’s offices – and 37% would be willing to pay for the service.29 As further evidence that email is gaining a foothold, a 2001 Harris Interactive poll found that many doctors were initially skeptical about the benefits of online tools, but were pushed by patients to start using email and now say it has increased patient satisfaction.30

Just one in ten health seekers has ever participated in an online support group or email list for people concerned about a particular health or medical issue. This activity showed little increase from last year – in both the August 2000 and June-August 2001 surveys, 9% of health seekers say they have ever participated in an online support group. Frequent health seekers are more likely to have joined an online support group – 13% of those who look for health information several times a month or more have done so, compared with 6% of those who look every few months or less.

In an online focus group discussion about why they do not participate in support groups, health seekers cited privacy concerns and the need for a “loving voice” instead of an on-screen note. One woman said, “It seems a bit personal to be chatting about things like that, plus you are exposed in a way on the Internet. Anyone could see what you wrote. Confidentiality is a real big thing with me.” But other participants say the benefits outweigh the risk, and one argued, “But it’s not like they know you, or will ever see you, so why not?”

Though the numbers are small, those who are most in need are more likely to take advantage of online support groups. Ten percent of health seekers in fair or poor health consulted an online support group the last time they searched for health information, compared with just 1% of those in excellent health. And 14% of those in fair or poor health have ever participated in an online support group, compared with 5% of those in excellent health.

Instead of treating the Internet as a vast library, some health seekers are joining online communities that allow them to provide support and keep up with the latest research. In an online focus group, one man living with emphysema said he spends eight hours per day online, scouring Web sites and passing on his knowledge to other members of his online support group, Efforts.31 He is grateful to the group for giving him hope, especially in the early days of his diagnosis, saying, “Knowledge is key in living with a progressive and fatal disease. I know pretty much what will take my life. Now I am learning how to hold it off.” Another focus group participant’s sister has epilepsy and was thinking about getting pregnant, so they dropped into an epilepsy support group to get advice before talking to her doctor about it. Indeed, 33% of health seekers have looked for information about a sensitive health topic that is difficult to talk about – some people feel more comfortable asking strangers or believe that someone who has been in their situation will advise them better than a health professional can.32

There is evidence that peer support can not only improve the way someone feels but cut costs as well. A randomized study of 580 people with chronic back pain showed that those who participated in an email discussion group with other patients and three expert moderators experienced less pain and saw their doctor less than those who did not participate.33

“Online patient-helpers” can work in concert with a doctor’s advice to improve care, as well. For example, Karen Parles, who did not smoke, was shocked by a diagnosis of terminal lung cancer at the age of 38. A librarian, she used her skills to research a new treatment and to share her concerns with an online support group, the Lung-Onc mailing list. Group members reassured her about lung surgery and gave her tips on how to sleep on sore ribs during recovery. After going through successful treatment for her own cancer, Parles created a clearinghouse of online information so that others could benefit from her research: lungcanceronline.org. Most Americans will hopefully never need such specialized resources – indeed few health seekers have sought out such support online – but those who do use it are forever grateful.34

Few take advantage of personalization

Only 8% of health seekers have set up a personal profile at a favorite health Web site or customized a health Web site so they receive only the information they are most interested in. Those who saw a doctor in the past year are more likely to have personalized a health Web site, as are those who believe the Internet has improved the way they take care of their health.

About 14 million Americans, or one fifth of all health seekers, have ever signed up for an electronic newsletter that emails the latest health news or medical updates. Those in fair or poor health are more likely to do so – 30% have signed up, compared with 17% of those in good health and 16% of those in excellent health. Those who have seen a doctor in the past year are more likely to have signed up, as are those who believe the Internet has improved the way they take care of their health.

Part Eight: Health searches for someone else

Searching on behalf of someone else

In January 2002, we conducted a national survey of Internet users, asking if they had helped another person deal with a major illness or health condition in the last two years. A substantial 39% of Internet users said yes, they had done that, and about one in four say their use of the Internet played a key role in the way they took care of that loved one. Therefore, it is not surprising that a large subset of health seekers are those who have gone online because someone they know was diagnosed – 81% of health seekers are included in this group. Indeed, the “last time” they went online for health information, 50% of all health seekers searched on behalf of someone else and 47% were looking for information for themselves. Another 2% of health seekers went online to do health research the last time, not necessarily with anyone in mind.

Health seekers take responsibility for all sorts of relatives and friends. Ten percent of health seekers searched on behalf of a child the last time they went online for medical advice, 10% for a spouse, 9% for a parent, 10% for another relative, 8% for a friend, 2% for a patient or client, and 1% for someone else. Those in the middle age groups are more likely than those in their twenties or senior citizens to search on someone else’s behalf. Men are more likely than women to do a health search for their spouse or partner.

E-patients whose last search was on someone else’s behalf were more likely to be problem solving or reacting to a specific situation than those who were looking on their own behalf. Seventy-two percent of “for someone else” health seekers looked for information about a specific illness or condition compared with 53% of “self” health seekers.

More “for someone else” health seekers looked for information about cancer and a certain treatment or medication, which supports the notion that a community often coalesces around someone who is dealing with a chronic illness like cancer. Friends and family educate themselves, forming an ad hoc support group. Indeed, these “for someone else” health seekers encompass a wider population than just parents and direct caregivers for the chronically ill. Focus group participants said they had searched for all sorts of people – a roommate with heartburn, a sister with skin problems, a mother who needed diabetic recipes, and a friend whose child was recently diagnosed with attention-deficit disorder. Said one participant, “I went to Ask Jeeves to find out about some symptom my mom was having and it described the symptoms as that of an ulcer-related problem. She went to the doctor and sure enough, she had three of them!”

Even e-patients living with a chronic illness become information gatekeepers for their friends and family and therefore caregivers in their own way. One chronically ill focus group participant said she searches on behalf of family members, including an adult daughter who has lupus.

Continual caregivers

Thirty-eight percent of health seekers have gone online for health information because they are caring for someone else. This is a different group from those who told us that they occasionally searched for someone else. Not surprisingly, women and people in the “sandwich generations” are more likely to identify themselves as caregivers. Forty-one percent of women health seekers have gone online as a caregiver compared with 33% of men. Thirty percent of health seekers in the18-29 age cohort have gone online as a caregiver, compared with 43% of 30-49 year-olds, 38% of 50-64 year-olds, and just 13% of health seekers over the age of 65. As an illustration of the “sandwich generation” dilemma, one focus group participant had recently looked up teething information for his baby and disease information for his father.

One in ten health seekers lives with someone who has a disability, handicap, or chronic disease. These caregivers are likely to act on what they find online and are more likely than non-caregivers to research drugs or alternative therapies online. Caregivers are almost twice as likely to ask a doctor new questions based on what they find online and are more likely to say they have been “significantly helped” by online health information. Indeed, the Internet had played an important or even crucial role for 25% of Internet users who had helped another person deal with a major illness in the past two years.

Parents

Four in ten health seekers are the parent or guardian of children under age 18, living at home. (Note that parents are no more likely to be health seekers than non-parents – about four in ten Internet users are parents.) Parents seem to take their health research responsibilities quite seriously, but may not adhere to all the search and validation strategies recommended by experts. For example, parents are less likely than non-parents to look to see who provides the information on a health Web site.

However, parents are more likely than non-parents to visit four or five sites and to spend more time online during a search (usually between 30 minutes and an hour). Parents are also more likely than non-parents to talk to their doctor about what they found online. Parents take a more deliberative approach to search engine results and are more likely to read the explanations of a search engine result instead of just starting at the top and working down.

In an online focus group, parents gave a range of reasons for going online for health information. One mother said she uses the Internet to try to “avoid lugging four kids to the doctor for something that I can take care of with over-the-counter medication.” Another mother goes online to see if her teenager is faking his illness to avoid school – if his symptoms check out, she takes him to the doctor. But someone else sounded a note of caution, saying, “If it’s the kids, then doctor is first.” All of the parents in the focus group said they appreciated knowing more about what to expect about their child’s illness, whether it was a teenager’s mononucleosis, a baby’s croup, or a young athlete’s torn ligament. These parents say they research homeopathic cures and ways to prevent illness, often starting at a search engine and then checking the information against what they find at trusted sites like WebMD, Babycenter.com, or Kidsdoctor.com. The repetition of information makes them feel it’s on target – or at least a starting point for further discussions with their doctors.