What health seekers want and how they hunt for it*

*This section is based largely on a special survey of 521 Internet users who go online for health care information.

Health seekers are mostly interested in investigating specific physical and mental ailments and their searches often are tied to visits to the doctor. However, they do not use the medical establishment or even friends to help guide their online searches when it comes to health care. Most health seekers treat the Internet as a vast, searchable library, relying largely on their own wits, and the algorithms of search engines, to get them to the information they need. Asked about the most recent time they got health-related information online, more than 30% checked out four or more Web sites. Younger health seekers and those with relatively high educations (at least some college-level work) are the most likely to have looked at multiple sites.

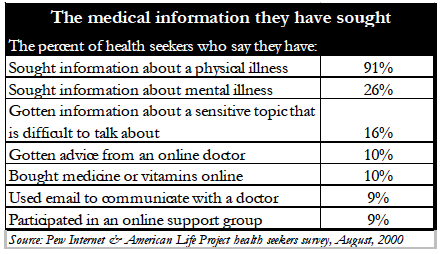

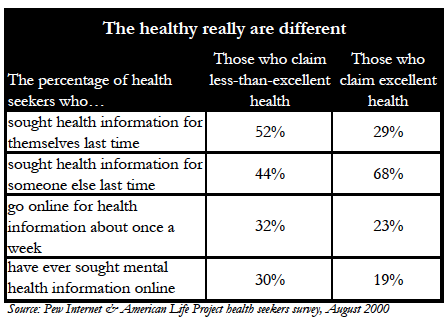

Ninety-one percent of health seekers have looked for information about a physical illness or condition and 26% have looked for information about a mental health issue like depression or anxiety. Less-healthy people are more likely to go online frequently for medically-related material and to have sought mental health information on the Web – 30% of those who say their health is less than excellent have sought material about mental illness, compared to 19% of those who say their health is excellent.

In contrast to their aggressive use of the Internet to do research about specific illnesses, health seekers are much less likely to have interacted with a doctor online, to have searched for general news about health and medicine, or to have bought a medical product or vitamins online. While online pharmacies promote the convenience of ordering online – and some skirt federal laws by dispensing sensitive items such as Viagra without a prescription – most health seekers are not yet using the Web as a substitute for the corner drug store. Only 10% of health seekers have purchased medicine or vitamins online.

Once they have found a useful site, health seekers are likely to go back to it again. Forty-two percent of health seekers have kept a health Web site bookmarked or saved as a “favorite place,” so they can go back to it regularly. Men are more likely to have bookmarked a site than women. And health seekers with more online experience are more likely to bookmark health sites – 45% of those with two or more years of experience have done this, compared to 36% of those with one year or less online experience.

The quality of information: Verify before trusting

Much of the health information available on the Web is not monitored for accuracy or quality. The Federal Trade Commission estimates that doctors review only about half of the content on health and medical Web sites. There is significant concern – especially on the part of advocates for the chronically ill – that patients may harm themselves based on inaccurate information or products obtained on the Internet. In October, for example, a Web-distributor of a home HIV test kit was brought up on charges of misleading his customers because the Federal Drug Administration did not, in fact, approve the faulty kit he sent to over 600 people in the U.S. The few studies by scholars and medical professionals have raised concerns about the reliability of online information. For instance, a 1999 survey by a team at the University of Michigan of 400 health sites found that half of them had not been scientifically reviewed and that 6% provided incorrect information. A study in 1997 that focused on the recommendations of 41 Web sites on how to deal with children’s fevers found that only four of the sites offered recommendations that were completely consistent with established guidelines in the medical community. Because of such fears, the American Medical Association and other medical groups have mounted major campaign to stress that consumers need to check the quality of information they get online.

Our survey confirms that the vast majority of Internet users are worried about getting bad information online. Fully 82% of those with Internet access – health seekers and nonseekers alike – say they are concerned about getting health information from an unreliable source online. Thus, it is not surprising that 58% of health seekers have looked to see what company or organization is providing the advice or information that appears on a health Web site. Health seekers with more education are more likely to check the source of health information – 61% of those with at least some college education have done so, compared to 46% of those with a high school education or less.

While there is a high anxiety among Internet users about health information online, 52% of users who have actually used health sites think that “almost all” or “most” health information they see on the Internet is credible. Forty-four percent of health seekers think that they can believe only “some” online health information. Just 1% of health seekers say “almost none” of the information is credible. Younger health seekers (under age 40) and those with less formal education are more likely to support the credibility of the health information on the Internet.

The absolute value of anonymity

Health seekers report a broad lack of interest in activities that might require them to identify themselves online. They want to be in control of the search for health information and they do not relish giving up personal information in the process. These Internet users would much rather stay anonymous than participate in an exchange about health information online where personal information was given up in return for access to a site or for customized content. In fact, the anonymity of Web searches for health information is sometimes seen by users as preferable to contact with human beings. Some 16% of health seekers have gone online to get information about a sensitive health topic that is difficult to talk about. Health seekers under the age of 40 are also more likely to have done this – 23%, compared to 10% of those over 40.

The vast majority of health seekers are concerned that a health site might disclose what they did online, most worry about their insurance companies or employers finding out what Web sites they have accessed, and most object to the idea of having their medical records posted even on a secure server.

Only 9% of health seekers have participated in an online support group for people who are concerned about the same health or medical issues. This contrasts sharply with another Pew Internet Project survey that found 36% of Internet users who had gone to a support-group site or one that provides information about a specific medical condition or personal situation. Again, it appears that health seekers are much more protective of their privacy than the general Internet population.

Don’t follow me around

Despite the fact that 89% of health seekers say they are concerned that a health Web site might sell or give away information about what they did online, just 24% of health seekers have clicked on a health or medical Web site’s privacy policy to read about how the site uses personal information. Health seekers who have expressed privacy concerns are more likely to have clicked on the privacy policy – 31%, compared to 21% of those who say they are not too concerned about privacy.

Most commercial health Web sites rely on advertising for a large portion of their revenue. Third party ad networks – such as Doubleclick – are interested in tracking and profiling Internet users so that customized ads and content could be placed on their screens. While many of the firms that run health sites say they do not profile based on the health-related material a user has accessed on their site, there is a great deal of concern among privacy advocates that advertisers can have access to sensitive health information without the consumers’ knowledge or consent.

There has not been an extensive review of the privacy policies of the entire universe of health-related Web sites. One important analysis of the 21 most heavily used health sites by the Health Privacy Project in early 2000 showed that several sites warn users that advertisers might have access to information, and that the sites have no “control” over this practice. But most of the policies were silent on the issue of profiling. Unless an Internet user is a very savvy Web surfer, she will never know if she is being tracked and profiled by a health Web site or those that advertise on the site.

Advocates of profiling argue that it brings several advantages to Internet users. They say that it helps Internet companies provide customized information and tailored ads that closely match a user’s interests. That helps the user get the information she needs and makes her aware of the products that matter most to her. This eliminates waste and makes it easy and quick for users to get the information they are seeking. Moreover, many point out that the growth of the Internet would not be taking place were it not for the fact that advertising supports the availability of much of the information online.

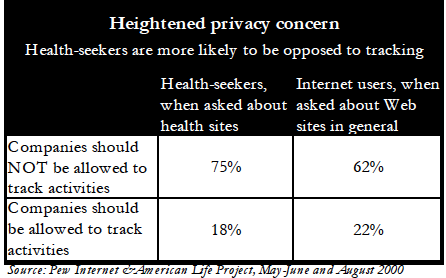

Yet, most health seekers still have a dim view of profiling. Three out of four health seekers (75%) think Internet companies that specialize in health or medical information should not be allowed to track the activities of people who visit their Web sites and just 18% of health seekers think Internet companies should be allowed to track activities. These findings show a higher level of concern about tracking among Internet users who visit health sites than among the general Internet population. In our previous study on trust and privacy online, 62% of all Internet users said Internet companies should not be allowed to track; 22% of all Internet users said companies should be allowed.

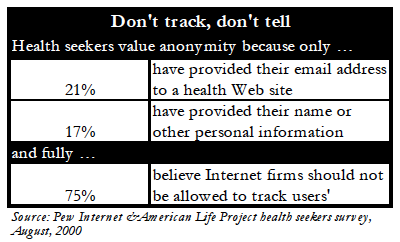

Health seekers are not very likely to have traded personal information with health-related Web sites – just 21% of health seekers have provided their email address at a health Web site. Seventeen percent of health seekers have provided their name or other personal information at a health Web site. This is a sharply lower rate of disclosure than takes place in the overall Internet population. In our previous report “Trust and Privacy Online,” we noted that 54% of all Internet users had given up their email address and other personal information in return for access to Web sites.

Yet while health seekers are determined to preserve their privacy, few have resorted to guerrilla tactics to get access to Web sites. Just 4% of health seekers have provided a fake name, email address, or other personal information in order to avoid providing real information at a health Web site. In our trust and privacy study, we found that 24% of Internet users have provided a fake name or personal information in order to gain access to a Web site.

An overwhelming majority of health seekers (87%) think there should be rules about how health and medical companies on the Internet can track activities. Just 10% don’t think rules are needed. Health seekers register slightly more caution about health Web sites’ business practices than the general Internet population’s attitude toward tracking. In our previous study on trust and privacy online, 81% of Internet users said there should be rules about Internet companies’ ability to track. Asked who should set the rules about if and how health companies can track online, 47% of health seekers said Internet users themselves should set rules, 25% said the federal government should set the rules, and 18% said Internet companies should set the rules.

And, in a finding that runs counter to existing federal policy, 81% of health seekers think people should be able to sue a health or medical company if it gave away or sold information about its Web site users after saying that it would not. Under current law, the Federal Trade Commission can take action, but individuals have no federal right to sue.

Case study: The last time each health seeker went online

To move beyond abstractions and get a picture of Internet users’ actual behavior, we asked health seekers to relate details about their most recent foray online for health information. For about one-quarter of respondents, it was a fresh memory. Some 23% of health seekers said the last time they went online to look for medical advice or information was within the last week; 35% said it was in the last month; 31% said it was in the six last months, and 10% said it was sometime more distant in the past than that.

The overwhelming majority of health seekers (83%) said they went online from home the last time they sought medical advice or information on the Internet. Only 14% went online from work.

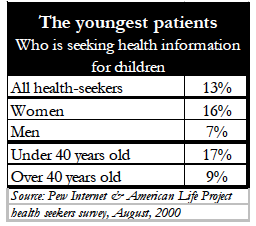

There are two major reasons health seekers go online for medical information – they are gathering information for themselves or they are gathering it for someone else. Our findings suggest that there are more health seekers looking for information on behalf of someone else than there are health seekers looking for themselves. When asked about their most recent search, 43% of health seekers were hunting for material for themselves and 54% were searching for information for someone else. That 54% breaks down this way: 13% of health seekers were looking for health information on behalf of a child, 8% were looking on behalf of a parent, 15% were looking on behalf of another relative, and an additional 18% were looking for health information on behalf of someone else.

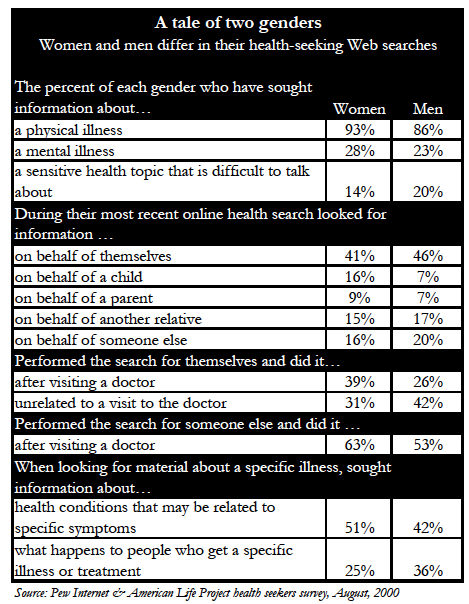

Women were more likely to seek health information on behalf of a child – 16% of women were doing this the last time then went online looking for medical material, compared to 7% of men. However, men were just as likely as women to have been seeking health information on behalf of a parent, another relative, or someone else.

The health seekers in our survey were more likely to be focused on an immediate problem, rather than general information or updates on medical news; 70% went online for information about a specific illness or condition. Thirteen percent sought information about fitness and nutrition, 11% sought basic news about health care, and 9% sought information about specific doctors, hospitals, or medicines.

Of those who were looking for online guidance about a specific illness or condition, 48% looked up symptoms of that illness, 30% sought information about medicines or treatments, and 29% were trying to find out what happens to people who contract a specific illness.

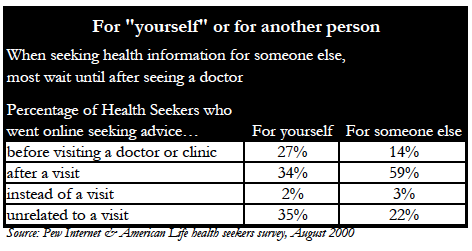

Because most are so focused on a specific illness, it is not surprising that health seekers seem to use Internet health sites to supplement a doctor’s advice or to understand a diagnosis better. Fifty-nine percent of those who sought information on behalf of another person did so after that person had visited a doctor or clinic and 34% of those who sought the information for themselves went online after a doctor’s appointment. Those who went online to seek health information for themselves were just as likely to be looking for this advice independent of a doctor’s visit (35%). A very small percentage of health seekers used the Web to get medical advice instead of visiting a doctor or clinic – just 2% of those who sought information for themselves and 3% of those who sought information on behalf of someone else.

The Internet users looking for health advice for their own problems were more likely to have checked the Web before a doctor’s appointment – 27%, compared to 14% of those who sought health information for others. Health seekers under the age of 40 were more likely to seek information in preparation for their own doctor’s appointment – 34%, compared to 21% of those over 40. Older health seekers were more likely to go online after they had visited a doctor or clinic (41%, compared to 26%).

Health seekers’ search for information had a scattershot quality. Three-quarters of those seeking health information were not content to get material from just one Web site. Only 17% in our sample did that. In contrast, half of health seekers (49%) visited two or three Web sites the last time they looked for health information online; 18% of health seekers went to four or five sites and 9% visited six to ten sites; 4% went to 11 or more sites.

Most health seekers were on their own in finding the sites they visited. An overwhelming majority of respondents (81%) said they found the health Web sites through an Internet search and 62% had not heard about the sites they ended up visiting before they began their search. Just 10% of health seekers had heard about the sites through an advertisement they spotted and 6% had gotten a recommendation from a friend or relative. A very few health seekers read about the site in a news article or followed up on a recommendation from a doctor, health insurance company, or HMO.

Once they completed their Web crawling, health seekers liked what they found. Fully 92% of health seekers say the information they found was useful and 81% said they learned something new the last time they went online for health information.

About half of health seekers (47%) who looked for information about their own health situation said the information they found online affected decisions about health treatments or the way they take care of themselves. Of those who said the information had an effect on the way they coped with the ailment, 51% reported that they changed the way they eat or exercise based on what they read online.

Those who sought information on behalf of another person were somewhat less likely to say that information found online affected decisions about the person’s health care. Still, more than a third (36%) of those hoping to help a loved one or friend said the Web resources affected the decisions they made about how to help the patient.

Of those swayed by what they read online, whether it was information for themselves or for someone else, 70% said the information affected their decision about how to treat an illness or condition. Fifty percent said the information lead them to ask a doctor new questions or to get a second opinion from another doctor. And 28% said the information affected their decision about whether to see a doctor.

The healthy try to help others; the less-healthy try to help themselves

The health status of those getting medical information online strongly correlates with the reasons a health seeker turns to the Web and on the results of her search. A majority of health seekers describe their health as less than ideal – 49% say it is “good,” 10% say it is “only fair,” and 2% say their health is “poor.” Thirty-nine percent of health seekers describe their own health status as “excellent.”

The last time they went online for health information, users in less-than-excellent health were more likely to have sought information for themselves than for other people. Fully half (50%) of those in less-than-excellent health say the information they gathered online during their most recent search affected their decisions about health treatments. That compares to 39% of those in excellent health who reported such an impact. Moreover, those in less-than-excellent health were more likely to report their hunt on the Web led them to ask new questions of their doctor or get a second opinion. Fully 52% of them reported such an effect, while 44% of those in excellent health said the online material led them to ask new questions or get a second opinion.

Those in excellent health were more likely to seek advice on behalf of someone else – a child, parent, relative, or another person.

How women and men differ in their online behavior

Women are more likely than men to have sought health information online. In general, women more frequently say they have searched for information about illnesses and about illness symptoms. Men are more likely than women to have sought information on behalf of themselves. Men are more likely than women to say their Web search affected their decisions about how to treat a disease. While women are more likely to seek material about the illness that is causing disease symptoms, men are more likely to hunt for information about the prognosis of a disease and what happens to people when they undergo certain treatments or take certain medications.

More often than men, women carry out health searches after a doctor’s visit. Women are also more likely to access online health information on behalf of their children. There are no notable gender differences when health seekers are looking for information on behalf of parents, other relatives, or other people. However, men are more likely than women to have used the Web information they gathered to ask follow-up questions of a medical professional.

Perhaps because they are the most active health seekers, women are more likely to register strong feelings about the benefits of online searches, especially those related to the wealth of information online and the convenience of online searches. And women are more likely than men to worry about getting unreliable information from the Web. Men’s and women’s attitudes about privacy are very similar. However, compared to women, men are slightly more privacy-conscious; they are more likely to have read a Web site’s policy. And men are somewhat more eager to take advantage of the fact that they feel anonymous online; they are more likely to have used the Web to search for information about sensitive health issues. Finally, men are more likely to have bookmarked a health site for future reference (48% to women’s 39%).

Fervent and engaged health seekers

Frequent users of health Web sites were more likely to be engaged in online activities that augment their health care. About 59% of health seekers report going online for health information at least once a month. There is not a notable gender difference in this, but age plays a role: 63% of health seekers under age 40 are frequently online for health information, compared to 54% who are over that age. Two-thirds of those living in households earning less than $50,000 report going online frequently for health information. And users who are less well physically use the Web more often than health seekers who describe their health as “excellent.” Some 62% of those in less-than-excellent health report going online to get medical advice at least once per month, while 53% of those in excellent health report frequent health searches online.

Internet users who said they go online for health information at least once a month are more likely to participate in an online support group, buy medicine or vitamins online, email their doctor, check a site’s privacy policy, describe a medical condition online to get advice, bookmark a favorite health site, verify the source of a site’s health information, and look for information about a physical or mental health issue. These highly engaged health seekers are also more likely to say the Internet has improved the way they take care of their health, compared to those who seek online health advice every few months or less often.