Thirty years ago, a wave of optimism swept across Europe as walls and regimes fell, and long-oppressed publics embraced open societies, open markets and a more united Europe. Three decades later, a new Pew Research Center survey finds that few people in the former Eastern Bloc regret the monumental changes of 1989-1991. Yet, neither are they entirely content with their current political or economic circumstances. Indeed, like their Western European counterparts, substantial shares of Central and Eastern European citizens worry about the future on issues like inequality and the functioning of their political systems.

Those in Central and Eastern European nations that joined the European Union generally believe membership has been good for their countries, and there is widespread support in the region for many democratic values. Still, even though most broadly embrace democracy, the intensity of people’s commitment to specific democratic principles is not always strong.

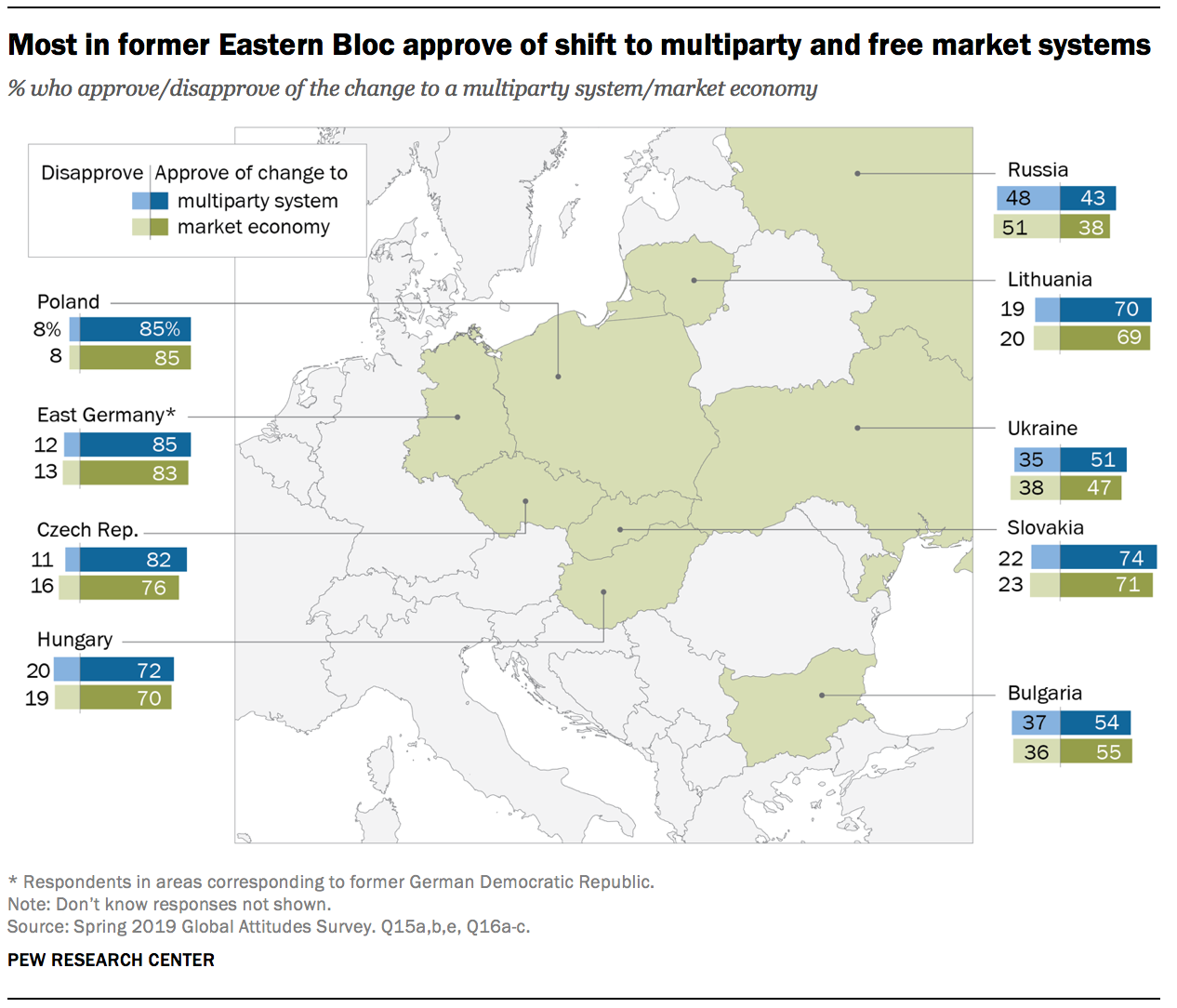

When asked about the shifts to multiparty democracy and a market economy that occurred following the collapse of communism, former Eastern Bloc publics surveyed largely approve of these changes. For instance, 85% of Poles support the shifts to both democracy and capitalism. However, support is not uniform – more than a third of Bulgarians and Ukrainians disapprove, as do roughly half in Russia.

These questions about democracy and a market economy were first asked in 1991, and then again in 2009. In a few nations – Hungary, Lithuania and Ukraine – support for both declined between 1991 and 2009 before bouncing back significantly over the past decade. Russia is the only country where support for multiparty democracy and capitalism is down significantly from 2009.

The varying levels of enthusiasm for democracy and free markets may be driven in part by different perspectives about the degree to which societies have made progress over the past three decades. Most Poles, Czechs and Lithuanians, and more than four-in-ten Hungarians and Slovaks, believe the economic situation for most people in their country today is better than it was under communism. And in these five nations, people are more likely to hold this view now than was the case in 2009, when Europe was struggling with the effects of the global financial crisis.

The varying levels of enthusiasm for democracy and free markets may be driven in part by different perspectives about the degree to which societies have made progress over the past three decades. Most Poles, Czechs and Lithuanians, and more than four-in-ten Hungarians and Slovaks, believe the economic situation for most people in their country today is better than it was under communism. And in these five nations, people are more likely to hold this view now than was the case in 2009, when Europe was struggling with the effects of the global financial crisis.

However, in Russia, Ukraine and Bulgaria, more than half currently say things are worse for most people now than during the communist era.

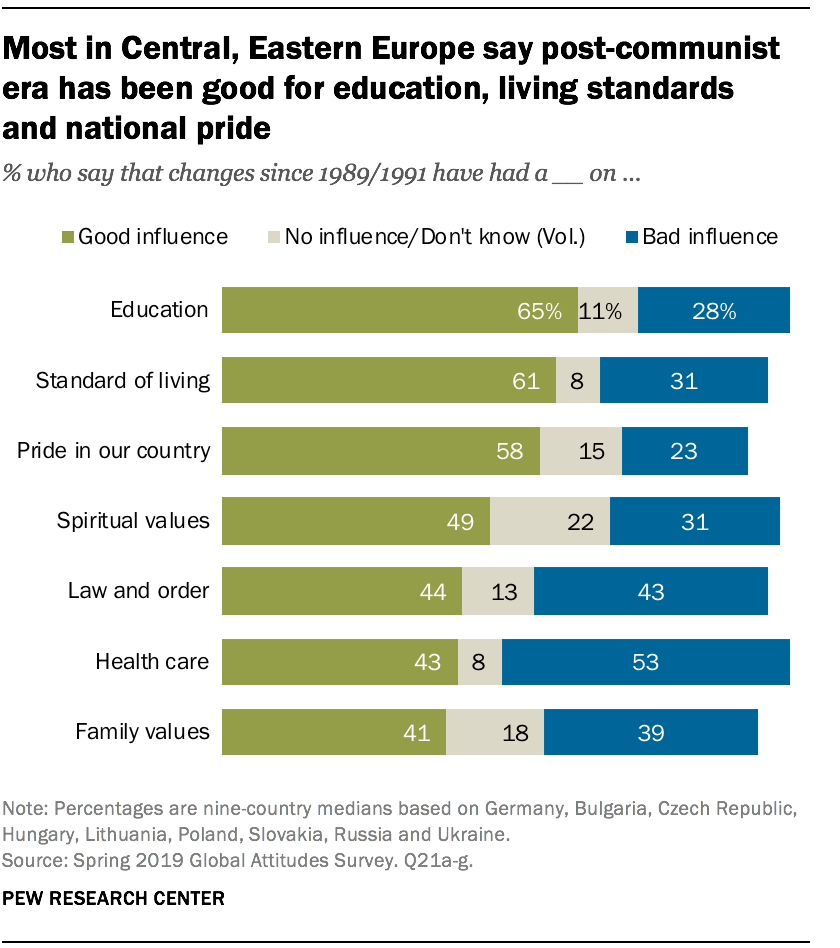

When asked whether their countries have made progress over the past three decades across a range of issues, the Central and Eastern European publics surveyed feel most positive about issues like education and living standards. But opinions are more divided about progress on law and order and family values, and most say the changes have had a negative impact on health care.

There is widespread agreement that elites have gained more from the enormous changes of the past 30 years than average citizens have. Large majorities in all Central and Eastern European nations polled think politicians and business leaders have benefited, but fewer say this about ordinary people.

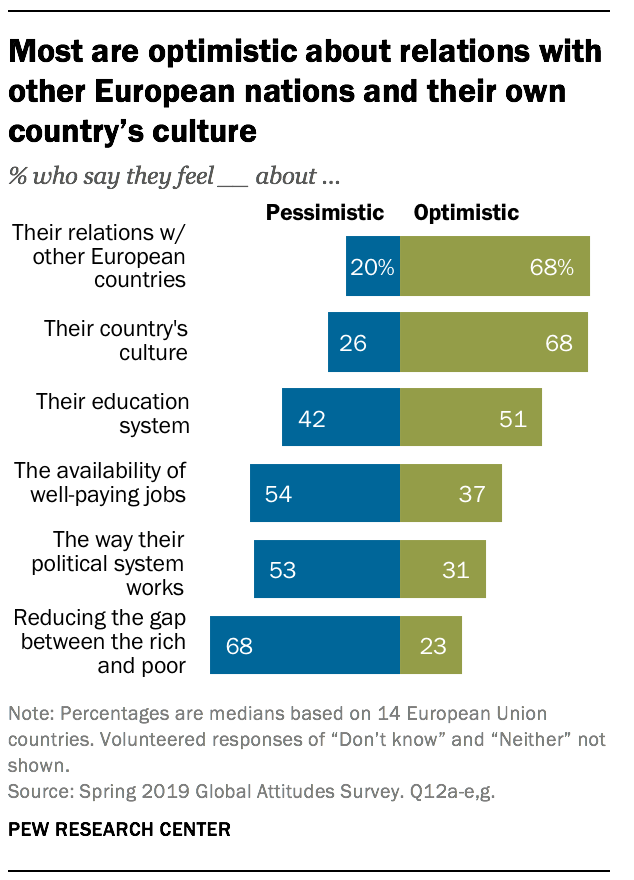

Just as there are different views about the progress nations have made in the recent past, opinions differ about the future as well. Across the former communist nations included in the survey, people are relatively optimistic about the future of their country’s relations with other European nations, but mostly pessimistic about the functioning of the political system and specific economic issues like jobs and inequality.

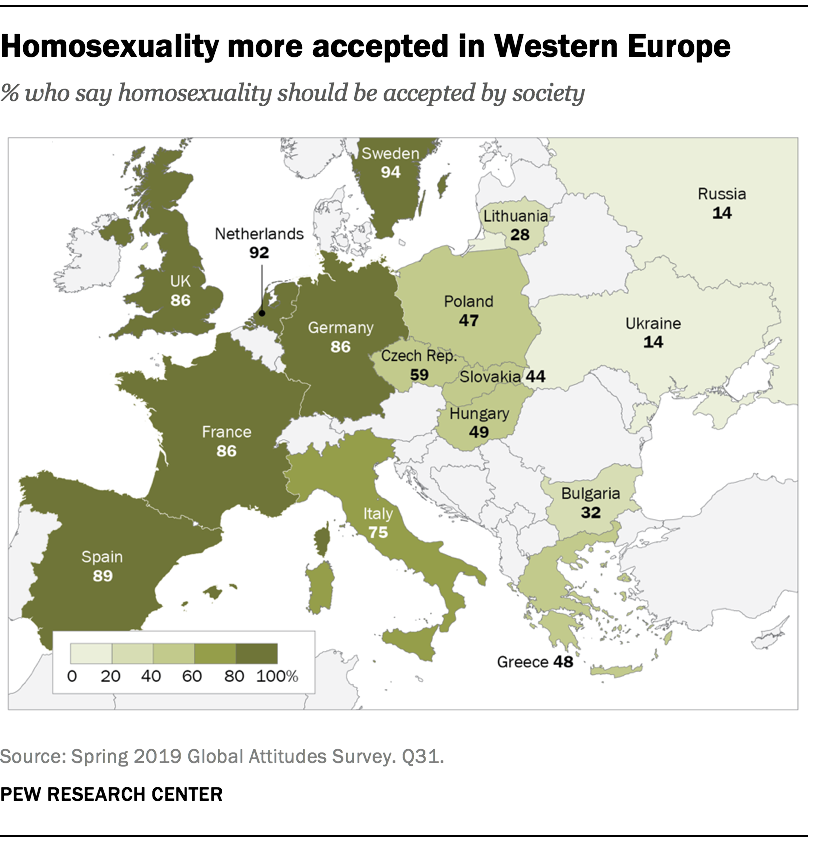

Across Europe, attitudes on some topics reflect a sharp East-West divide. On social issues like homosexuality and the role of women in society, opinions differ sharply between West and East, with Western Europeans expressing much more progressive attitudes.

Across Europe, attitudes on some topics reflect a sharp East-West divide. On social issues like homosexuality and the role of women in society, opinions differ sharply between West and East, with Western Europeans expressing much more progressive attitudes.

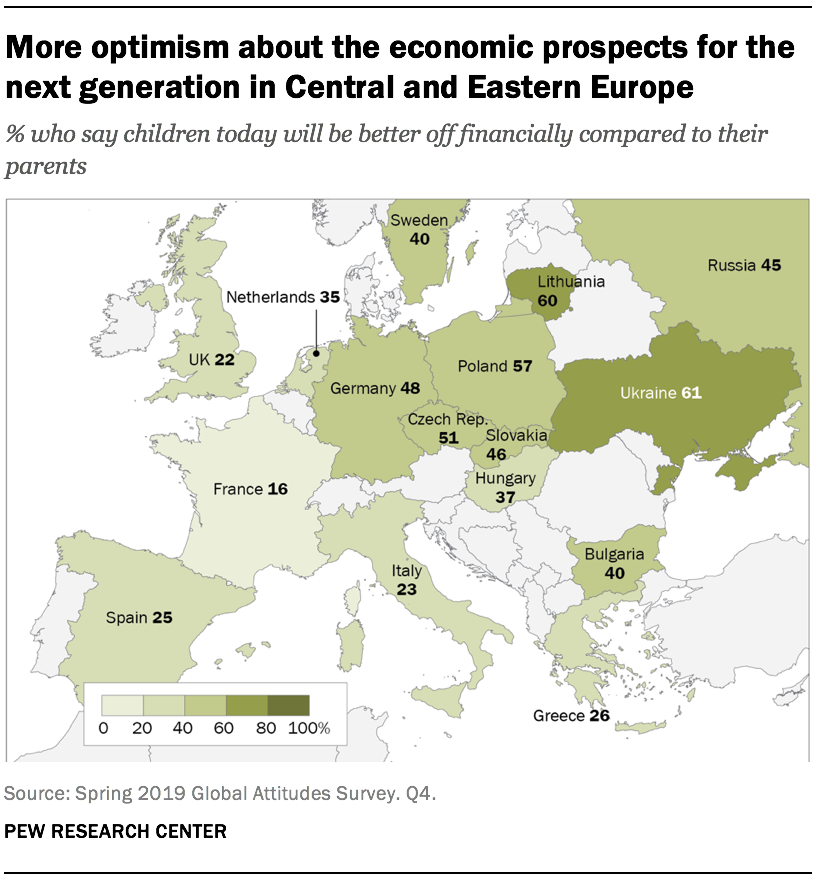

There is also a divide on views about the economic future. Regarding the economic prospects for the next generation, hope is somewhat more common in former Eastern Bloc nations. Around six-in-ten Ukrainians, Poles and Lithuanians believe that when children in their country grow up, they will be financially better off than their parents. In contrast, roughly a quarter or fewer hold this view in Greece, Spain, Italy, the United Kingdom and France.

There is also a divide on views about the economic future. Regarding the economic prospects for the next generation, hope is somewhat more common in former Eastern Bloc nations. Around six-in-ten Ukrainians, Poles and Lithuanians believe that when children in their country grow up, they will be financially better off than their parents. In contrast, roughly a quarter or fewer hold this view in Greece, Spain, Italy, the United Kingdom and France.

On views about the state of the current economy, however, the main division is often between a relatively satisfied northern Europe and a mostly unhappy south, where many people have not recovered from the economic crisis of a decade ago.

On views about the state of the current economy, however, the main division is often between a relatively satisfied northern Europe and a mostly unhappy south, where many people have not recovered from the economic crisis of a decade ago.

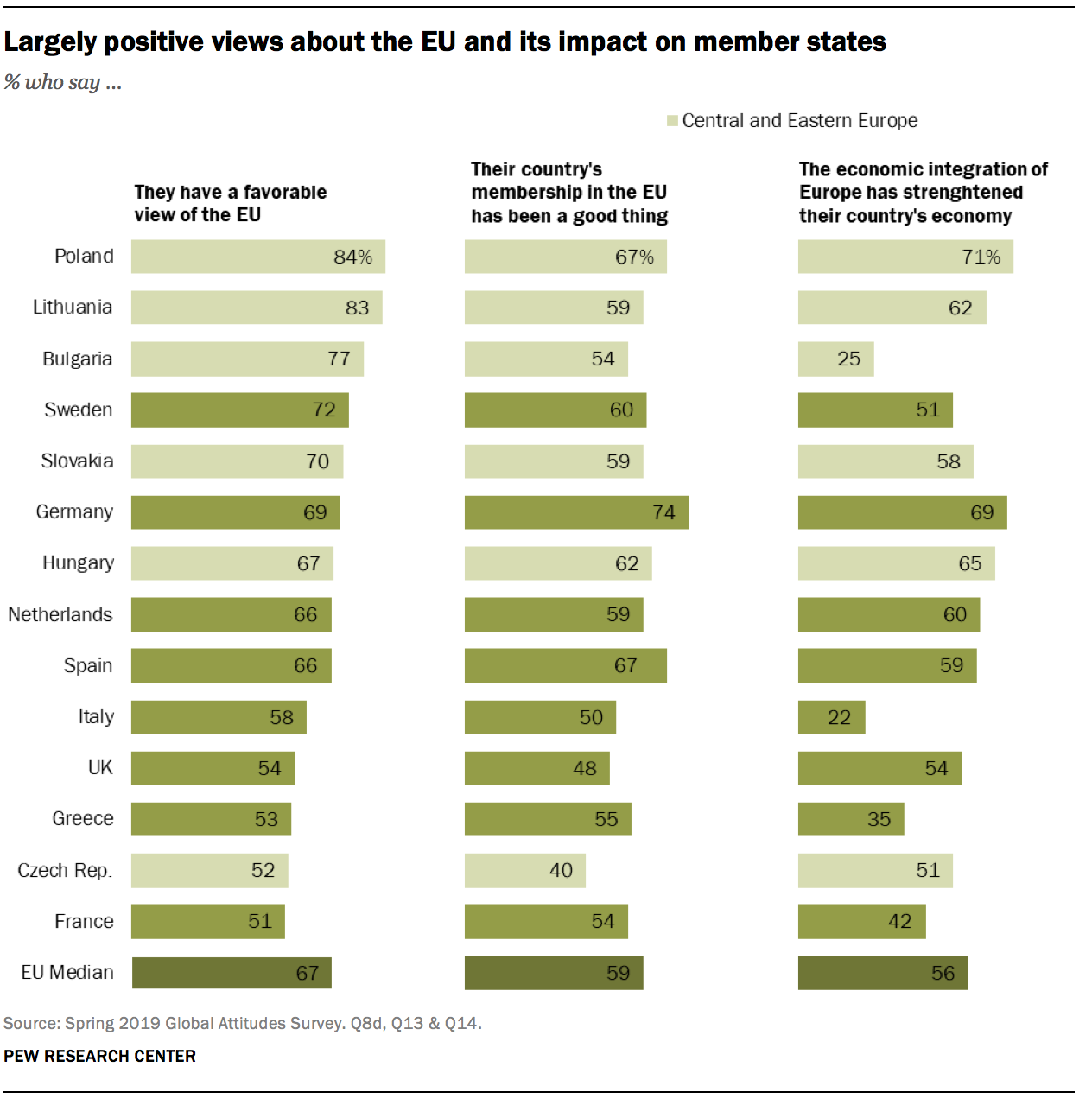

EU member states are mostly united in their support for the broad European project. The EU gets largely favorable ratings, most say membership has been good for their countries, and most believe their countries have benefited economically from being a part of the EU, although positive reviews for the institution are hardly universal. The most favorable ratings for the EU are found in former communist nations Poland and Lithuania, both of which became member states in 2004.

As previous Pew Research Center studies have shown, Europeans tend to believe in the ideals of the EU, but they have complaints about how it functions. Most have said the EU stands for peace, democracy and prosperity, but most also believe it is intrusive and inefficient and that Brussels does not understand the needs of average citizens.

The two former communist nations in the survey that have not joined the EU – Russia and Ukraine, both of which were part of the Soviet Union – look very different from the EU nations surveyed on a number of measures. They are less approving of the shifts to democracy and capitalism, less supportive of specific democratic principles and less satisfied with their lives.

These are among the key findings from a new Pew Research Center survey of 17 countries, including 14 EU nations, Russia, Ukraine and the United States. The survey covers a broad array of topics, including views about the transition to multiparty politics and free markets, democratic values, the EU, Germany, political leaders, life satisfaction, economic conditions, gender equality, minority groups and political parties.

The survey was conducted among 18,979 people from May 13 to Aug. 12, 2019. This study builds upon two previous surveys by Pew Research Center and its predecessor. The first was conducted by the Times Mirror Center for the People & the Press (a forerunner of Pew Research Center) from April 15 to May 31, 1991. The second was a poll conducted by Pew Research Center from Aug. 27 through Sept. 24, 2009, just prior to the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall.

The 1991 survey took place prior to the dissolution of both Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union. Even though Czechoslovakia was a single country in 1991, we show 1991 results for geographic areas that correspond to the present-day Czech Republic and Slovakia. In 1991, Lithuania, Russia and Ukraine were surveyed as republics of the Soviet Union. In Ukraine in 2019, we do not survey in Crimea or areas under conflict in the eastern oblasts of Luhansk and Donetsk. For more information, see the Methodology.

Most Europeans support democratic values, but many worry about how democracy is working

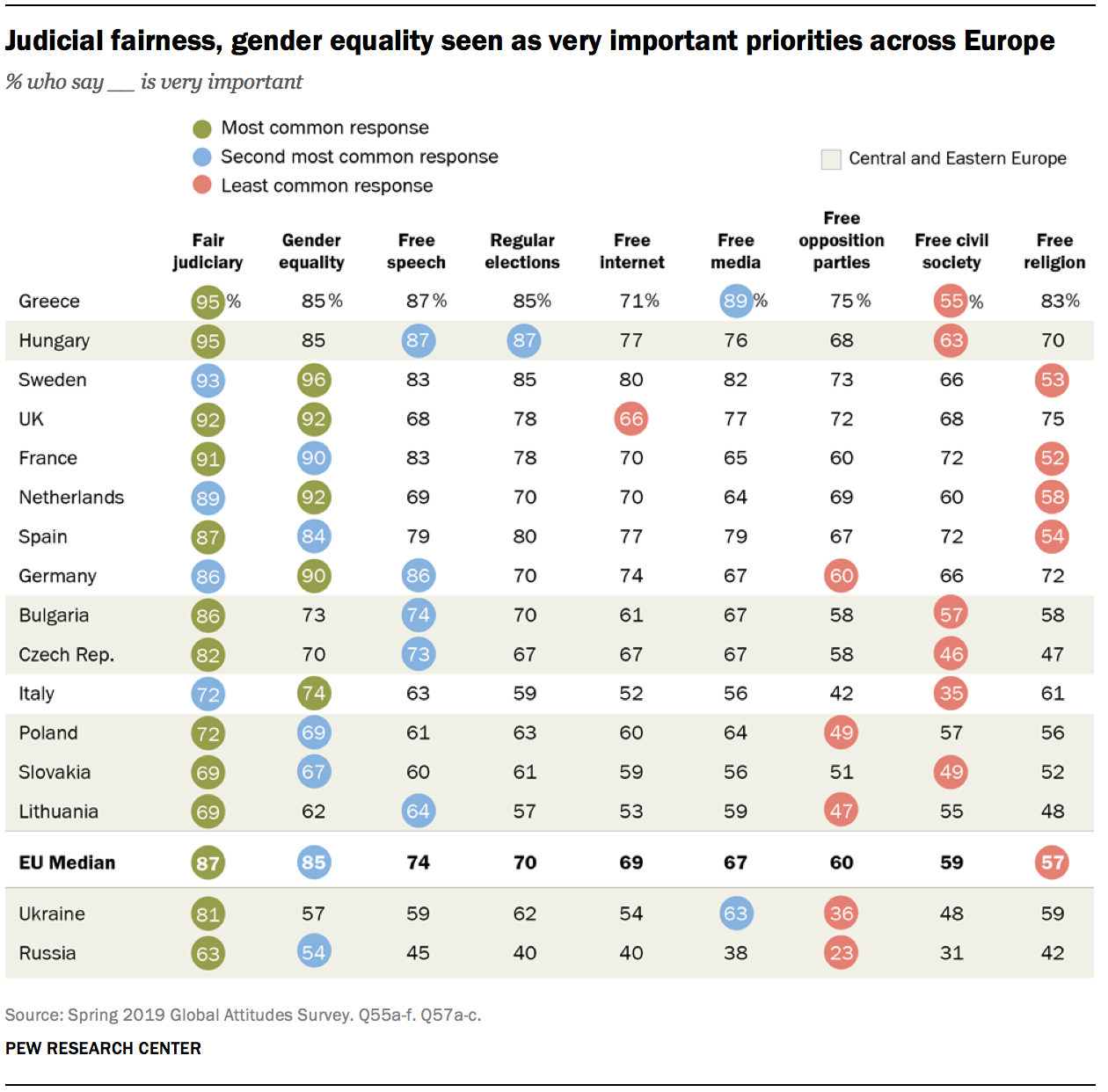

Across all 14 EU countries included in the study, as well Russia, Ukraine and the United States, there is broad support for specific democratic rights and institutions. Respondents were presented with nine different features of liberal democracy, then asked how important it is to have each one in their country. Majorities in every nation polled said all of these nine factors are at least somewhat important, and in most countries, large majorities expressed this view.

However, attitudes differ regarding whether these principles are very important. Large majorities typically consider having a fair judicial system and gender equality very important, but support for religious freedom and allowing civil society groups to operate freely is in some cases less enthusiastic.

And there are notable differences across countries. Western Europeans are generally more likely than Central and Eastern Europeans to rate these rights and institutions as very important. Russians consistently express the lowest levels of support. Americans, meanwhile, are often especially likely to consider these principles very important.

This is consistent with other Pew Research Center surveys, which have found that while democracy is a popular idea around the world, the intensity of people’s commitment to it is not always strong. For instance, representative democracy is widely embraced, but significant shares of the public in many nations are open to nondemocratic forms of government as well. People support free expression, but there are strong differences across nations regarding the appropriate boundaries of permissible speech. And, as the current survey shows, fundamental democratic rights and institutions are widely embraced, but some give those principles a less than full-throated endorsement.

There are also large cross-national differences on how people view the current state of democracy in their country. In Sweden, the Netherlands, Poland and Germany, 65% or more are satisfied with the way democracy is working, while in Greece, Bulgaria, the UK, Italy and Spain two-thirds or more are dissatisfied.

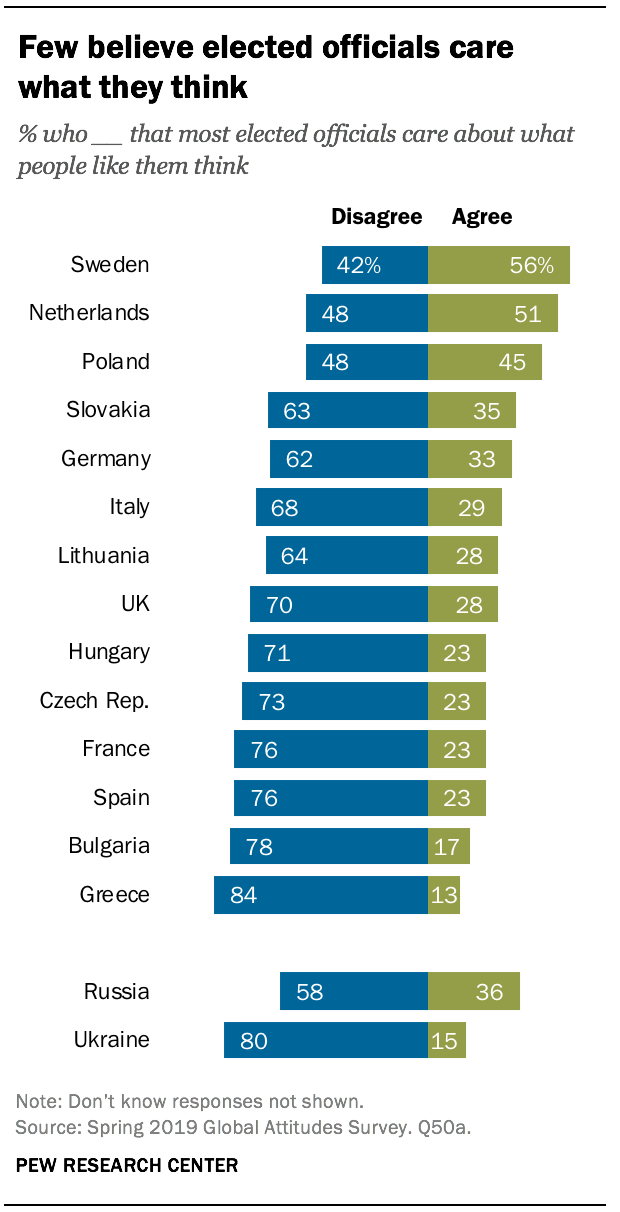

One factor driving dissatisfaction with the way democracy is working is frustration with political elites, who are often perceived as out of touch with average citizens. Across the EU nations polled, a median of 69% disagree with the statement “Most elected officials care about what people like me think.” Majorities also share this perspective in Russia, Ukraine and the U.S.

One factor driving dissatisfaction with the way democracy is working is frustration with political elites, who are often perceived as out of touch with average citizens. Across the EU nations polled, a median of 69% disagree with the statement “Most elected officials care about what people like me think.” Majorities also share this perspective in Russia, Ukraine and the U.S.

In former Eastern Bloc nations, there is a widespread perception that politicians – and to a somewhat lesser extent, business people – have benefited greatly from the changes that have taken place since the end of the communist era. The belief that ordinary people have benefited is much less common, although the share of the public expressing this view has increased in many countries since 2009.

Another sign of frustration with political elites and institutions is the poor ratings for most European political parties. The survey asked respondents whether they have a favorable or unfavorable opinion of major parties in their country. In total, we asked about 59 parties across the 14 EU nations surveyed – but only six of these parties receive a favorable rating from half or more of the public.

Despite the misgivings many have about the way democracy is working, most still believe they can have an influence on the direction of their country. In every nation surveyed, roughly half or more agree with the statement “Voting gives people like me some say about how the government runs things.” And about seven-in-ten or more express this view in Spain, Sweden, Slovakia, Ukraine, the Czech Republic and Poland, as well as in the U.S.

Mostly positive attitudes toward the EU

One of the most significant political developments of the past three decades has been the integration of many Central and Eastern European nations into the European Union. Of course, another major development in recent years has been the rise of populist political parties and movements throughout Europe that have questioned the value of European integration and railed against Brussels on a variety of fronts. The United Kingdom has gone so far as to vote to leave the EU.

Overall, attitudes toward the EU are positive. Roughly half or more in every member state surveyed express a favorable opinion of the institution. The EU gets its highest ratings in Poland and Lithuania, two nations that did not join the union until 2004, and its third highest rating is in Bulgaria, which didn’t join until 2007. In the UK, Greece, Czech Republic and France, attitudes toward the EU are less positive, though still on balance favorable.

When asked to reflect on their country’s EU membership, respondents mostly say it has been a good thing, especially in Germany, Poland and Spain, where at least two-in-three express this view. In contrast, only half or fewer believe membership has been good in Italy, the UK and the Czech Republic.

Publics are somewhat more lukewarm about the economic impact of EU membership. When asked whether the economic integration of Europe has strengthened or weakened their country’s economy, a median of 56% across the 14 member states surveyed say it has strengthened it. However, just 42% in France, 35% in Greece, 25% in Bulgaria and 22% in Italy share this opinion.

Overall, views about the general impact of EU membership, and the specific economic impact of membership, have improved in recent years as economic concerns have eased somewhat in many nations. Even, for example, in a country like France, where there is still a lot of skepticism about the value of economic integration, opinions have improved – in 2015, just 31% felt integration had helped their economy, compared with the 42% registered in the current survey.

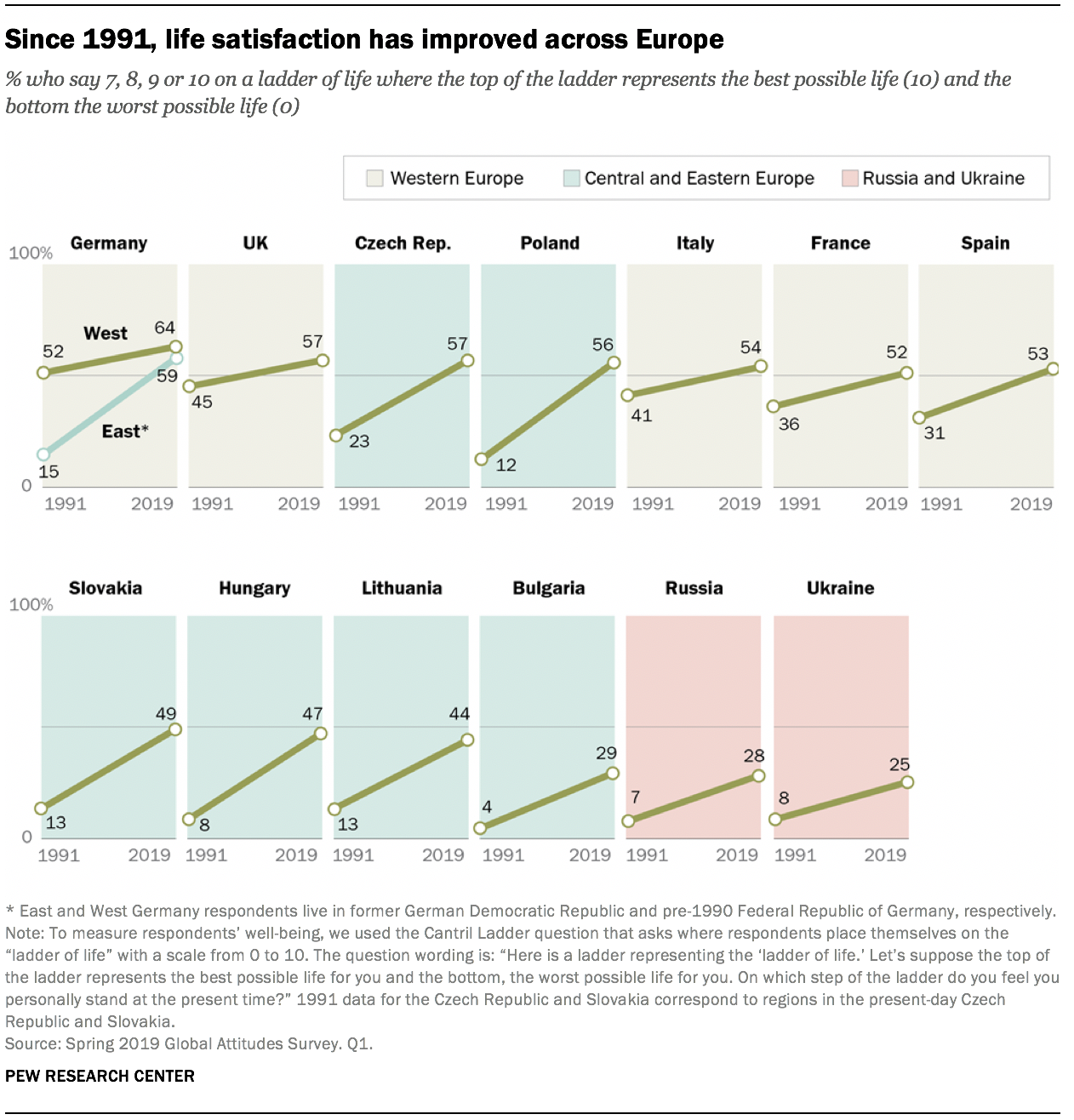

Life satisfaction is up significantly over the past three decades

Among the survey’s most positive findings is that people in former communist nations, as well as in Western Europe and the United States, are feeling better about their own lives than was the case when these countries were surveyed in 1991. The improvement in several of the Central and Eastern European countries that have joined the EU is dramatic. In 1991, as Poland was still coming to grips with the transition to democracy and capitalism, just 12% of Poles rated their lives a 7, 8, 9 or 10 on a 0-10 scale, where 10 represents the best possible life and 0 the worst possible life. Today, 56% do so.

However, improvements are not limited to the former Eastern Bloc. Even though their countries have experienced economic challenges in recent years, people in France and Spain are much more positive about their lives than they were almost three decades ago.

Overall, life satisfaction tends to be higher in wealthier nations. The four countries with the highest per capita incomes in this study – the U.S., the Netherlands, Germany and Sweden – also have the highest levels of life satisfaction, while the nation with the lowest per capita income, Ukraine, has the lowest level.

Europeans are both hopeful and apprehensive about the future

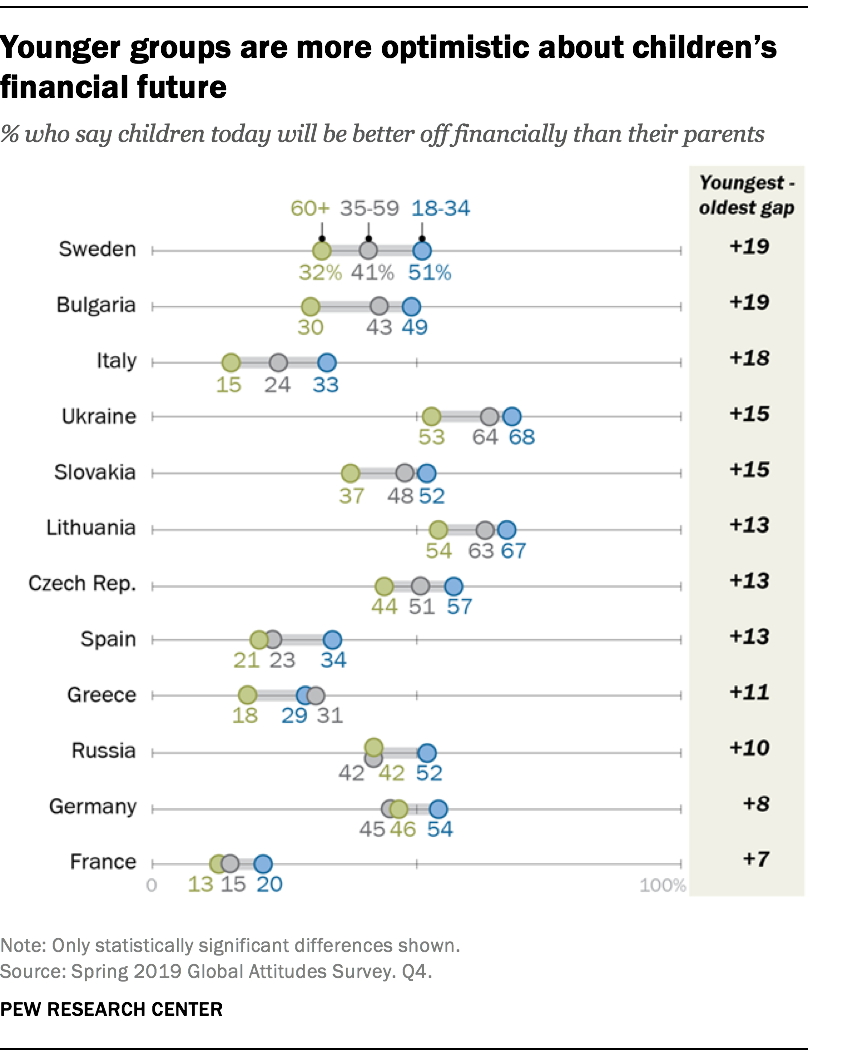

When thinking about the future of their countries, Europeans express a mixture of optimism and pessimism. Regarding the economic prospects for the next generation, hope is more common in Central and Eastern Europe. Around six-in-ten Ukrainians, Poles and Slovaks believe that when children in their country grow up, they will be financially better off than their parents. In contrast, roughly a quarter or fewer hold this view in Greece, Spain, Italy, the UK and France.

When thinking about the future of their countries, Europeans express a mixture of optimism and pessimism. Regarding the economic prospects for the next generation, hope is more common in Central and Eastern Europe. Around six-in-ten Ukrainians, Poles and Slovaks believe that when children in their country grow up, they will be financially better off than their parents. In contrast, roughly a quarter or fewer hold this view in Greece, Spain, Italy, the UK and France.

When asked how they feel about the future of different topics in their countries, opinions vary widely across issues. People are largely optimistic about the future of their country’s relations with other European nations, and they feel the same way about their country’s culture. However, there is considerably less optimism about the future regarding well-paying jobs and the way the political system works. European publics are especially pessimistic about reducing economic inequality – across the 14 EU nations surveyed, a median of just 23% are optimistic about reducing the gap between rich and poor in their country.

More optimism among young people

On a host of issues, young people have a relatively positive outlook about the past, present and future of their countries. In former communist nations, 18- to 34-year-olds are generally more likely than their older counterparts to believe the shift to a market economy has been good for their country, and they are also more likely to think the changes that have taken place over the past three decades have benefited ordinary people.

On a host of issues, young people have a relatively positive outlook about the past, present and future of their countries. In former communist nations, 18- to 34-year-olds are generally more likely than their older counterparts to believe the shift to a market economy has been good for their country, and they are also more likely to think the changes that have taken place over the past three decades have benefited ordinary people.

Across many European countries, those under 35 are more satisfied with the current direction of their countries. They also express more favorable opinions of the EU, more positive attitudes toward Muslims and are more accepting of homosexuality.

And there is greater optimism about the long-term economic future among young people. In 12 nations, those ages 18 to 34 are more likely than those 60 and older to believe that children in their country will be better off financially than their parents when they grow up.

Perceptions of gender equality

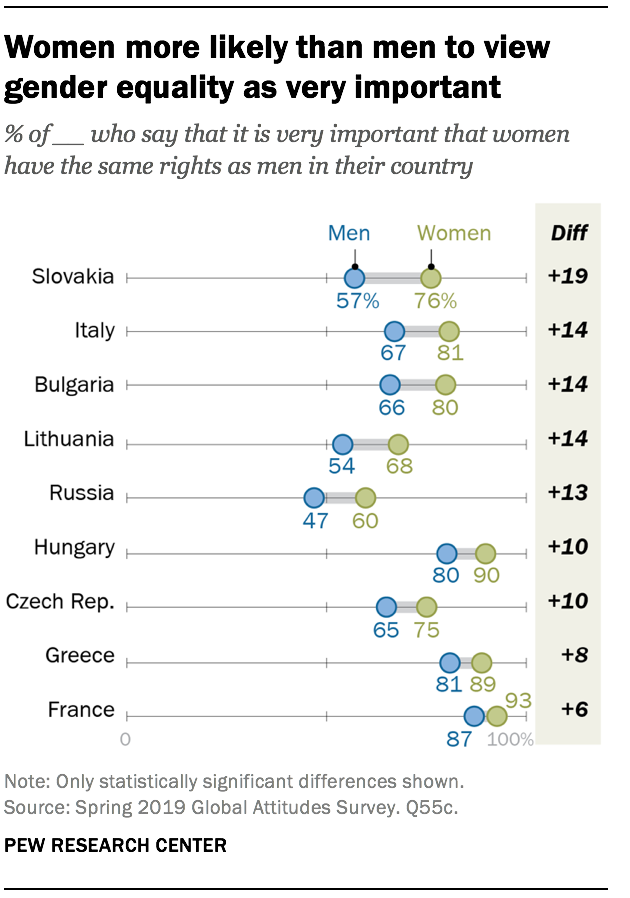

Although Europeans tend to place a high priority on having gender equality in their countries, in several nations women are more likely than men to hold this view. In nine of the nations surveyed, women are especially likely to say it is very important that women have the same rights as men in their country. Double-digit gender gaps on this question are found in Slovakia, Italy, Bulgaria, Lithuania, Russia, Hungary and the Czech Republic.

Although Europeans tend to place a high priority on having gender equality in their countries, in several nations women are more likely than men to hold this view. In nine of the nations surveyed, women are especially likely to say it is very important that women have the same rights as men in their country. Double-digit gender gaps on this question are found in Slovakia, Italy, Bulgaria, Lithuania, Russia, Hungary and the Czech Republic.

In many European nations, attitudes toward gender roles and marriage have shifted since 1991, with more people now preferring a marriage where both the husband and wife have jobs and take care of the household, rather than one where the husband provides for the family and the wife takes care of home and children. For instance, in 1991, 57% of Poles preferred traditional marriage roles, compared with just 27% today.

When it comes to gender and the economic sphere, majorities in most countries disagree with the statement “When jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women.” Still, substantial shares of the public agree with this statement in several nations, including roughly six-in-ten in Slovakia and four-in-ten or more in Greece, Poland, Bulgaria and Italy.

Right-wing populists more distrustful of EU, minorities

Political systems in Europe and elsewhere have been disrupted over the past few years by the growth of anti-elite sentiments and the rise of populist parties, leaders and movements – mostly, but not exclusively, on the political right. Numerous issues have fueled the spread of populism, and the current survey highlights a variety of topics where supporters of populist parties stand out.

Political systems in Europe and elsewhere have been disrupted over the past few years by the growth of anti-elite sentiments and the rise of populist parties, leaders and movements – mostly, but not exclusively, on the political right. Numerous issues have fueled the spread of populism, and the current survey highlights a variety of topics where supporters of populist parties stand out.

People who express a favorable opinion of right-wing populist parties are generally more likely to hold unfavorable views of the EU and to believe the economic integration of Europe has been bad for their countries. For more on how this survey defines populist parties in Europe, see Appendix A.

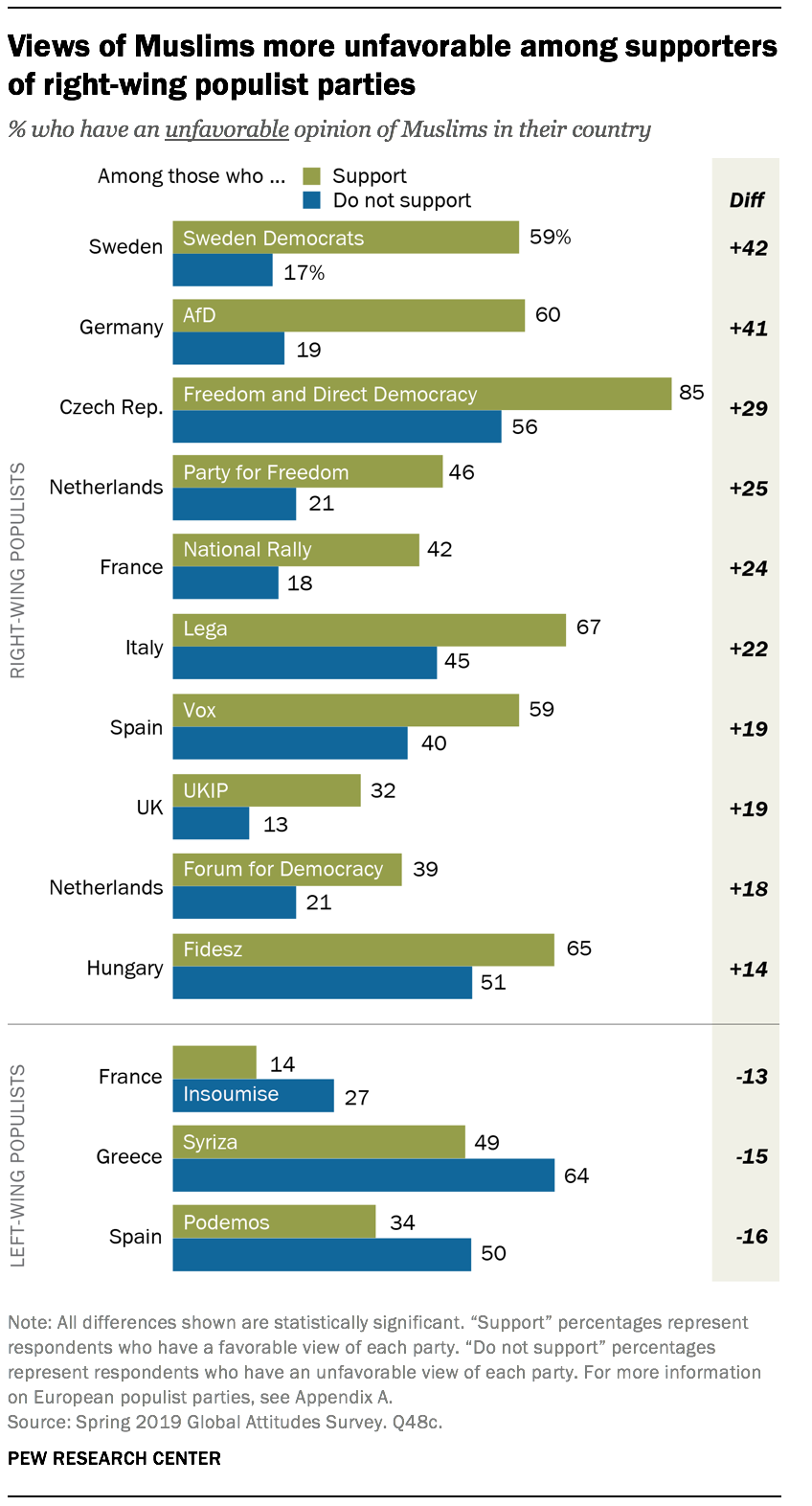

They are also less accepting of homosexuality and more negative toward minority groups. For instance, 59% of Swedes with a positive opinion of the right-wing populist Sweden Democrats express an unfavorable opinion of Muslims in their country; among those with a negative view of the Sweden Democrats, just 17% see Muslims negatively. How people feel about right-wing populist parties also shapes attitudes toward Muslims in Germany, the Czech Republic, the Netherlands, France, Italy, Spain, the UK and Hungary.

A different pattern emerges, however, regarding left-wing populist parties. In France, Greece and Spain, people with favorable views of left-wing populist parties tend to have more positive attitudes toward Muslims in their country.

Country Spotlights:

Germany

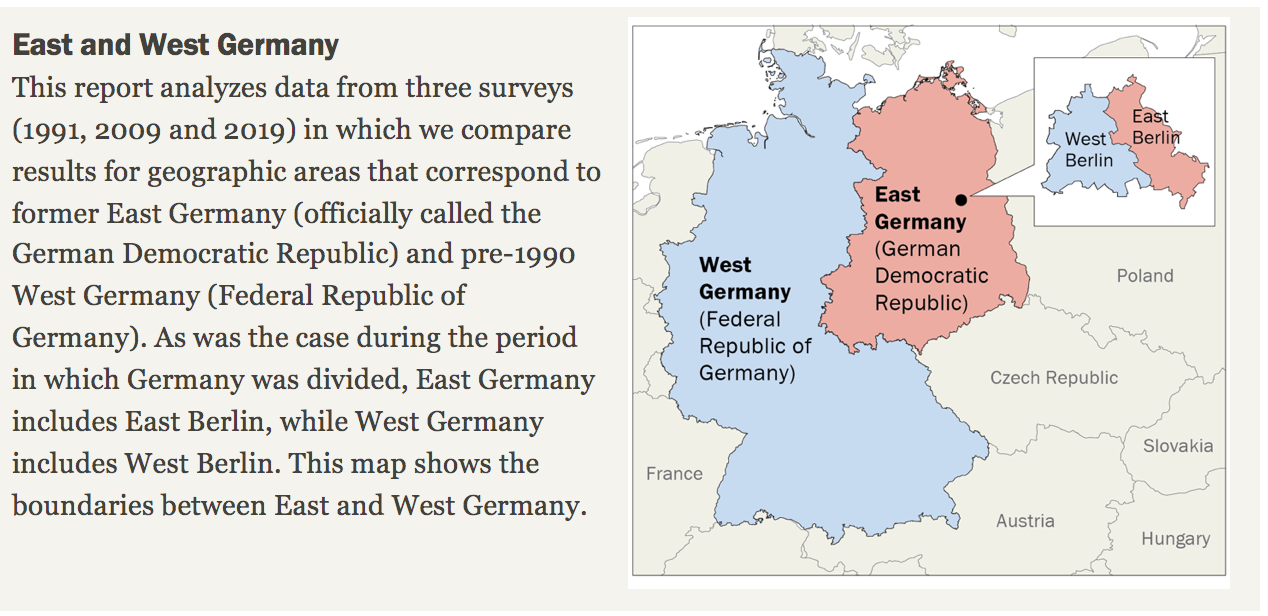

The survey has certain questions that were asked only in former East Germany, and on many other questions there are substantial differences between those Germans living in the East and the West.

- Around nine-in-ten Germans living in both the West and East say that German unification was a good thing for Germany. However, majorities on both sides of the former Iron Curtain say that since unification, East and West have not achieved the same standard of living.

- East Germans are less satisfied with the way democracy is working in Germany and the overall direction of the country than those in the West. And fewer East Germans have a favorable view of the European Union.

- Life satisfaction in East Germany has skyrocketed since 1991 and now is closing in on opinions in the West. In 1991, 15% of those living in former East Germany said their life was a 7, 8, 9, or 10 on a 0-10 scale, but in 2019 that ballooned to 59%. Meanwhile, life satisfaction in the West has also increased since 1991, from 52% to 64% today.

United States

While American and European attitudes are similar on some key issues, there are others where the two sides of the Atlantic have less in common.

- Americans are more likely than Europeans to say most tenets of democracy are very important for the country, but especially the ability for the media to report without government censorship and freedom of religion. Americans are about as likely as Western Europeans to say that honest, regular elections with at least two parties are very important for their country, and both see this as more important than most in Eastern Europe.

- When it comes to attitudes about LGBT rights, Americans are generally more progressive than Central and Eastern Europeans. For example, today 72% of Americans say homosexuality should be accepted by society. While lower than the median of 86% in Western Europe, this is much higher than the median of 46% who say the same in Central and Eastern Europe.

- Regarding attitudes about individualism, Americans are less likely than Europeans to say forces outside of people’s control determine success in life.

Roadmap to the report

The chapters that follow discuss these findings and others in more detail:

- Chapter 1 examines attitudes in Central and Eastern Europe toward the political and economic changes that occurred following the fall of communism as well as how these changes have influenced different groups and aspects of society.

- Chapter 2 explores the democratic institutions and rights that people across Europe view as important for their country.

- Chapter 3 looks at satisfaction with the way democracy is working, including whether voting gives people a say in what happens in their country.

- Chapter 4 reviews attitudes toward the European Union and major European leaders, and examines people’s optimism, or pessimism, about various aspects of their society.

- Chapter 5 explores national conditions, such as views about the current economic situation, as well as life satisfaction.

- Chapter 6 considers European attitudes toward minority groups such as Muslims, Jews and Roma.

- Chapter 7 reviews beliefs about gender equality in society, marriage and employment.

- Chapter 8 examines ratings of European political parties.