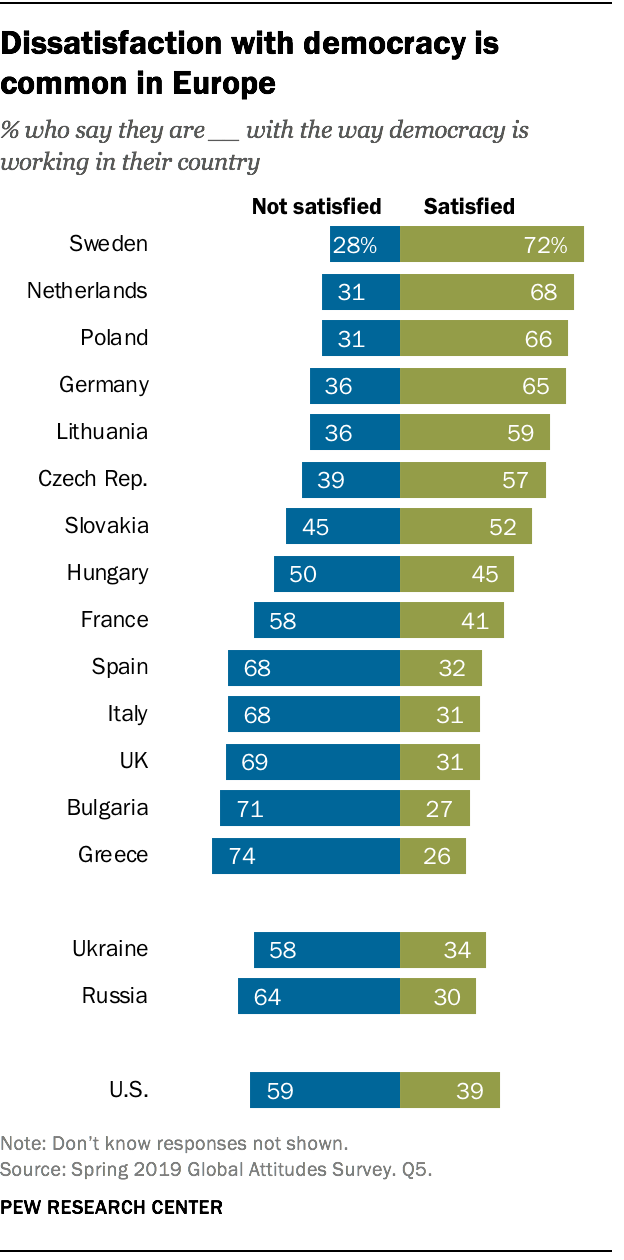

Across Europe, satisfaction with democracy is mixed. In Sweden, the Netherlands, Poland and Germany, roughly two-thirds or more are satisfied with the state of democracy in their country (72%, 68%, 66% and 65%, respectively). By contrast, in Greece, the UK, Italy, Spain and France, majorities are dissatisfied with how democracy is functioning. By a more than two-to-one margin, Greeks, Britons, Italians and Spaniards are also more dissatisfied with democracy in their country than satisfied.

Across Europe, satisfaction with democracy is mixed. In Sweden, the Netherlands, Poland and Germany, roughly two-thirds or more are satisfied with the state of democracy in their country (72%, 68%, 66% and 65%, respectively). By contrast, in Greece, the UK, Italy, Spain and France, majorities are dissatisfied with how democracy is functioning. By a more than two-to-one margin, Greeks, Britons, Italians and Spaniards are also more dissatisfied with democracy in their country than satisfied.

Across the six Central and Eastern European countries surveyed, satisfaction is somewhat higher. But this varies from a high in Poland, where about two-thirds are satisfied, to a low of 27% in Bulgaria. Relatively few Ukrainians (34%) or Russians (30%) are satisfied.

Within Germany, those who live in West Germany are somewhat more satisfied (66%) with the way democracy is working than those who live in East Germany (55%).

Democratic satisfaction has increased across Central and Eastern Europe

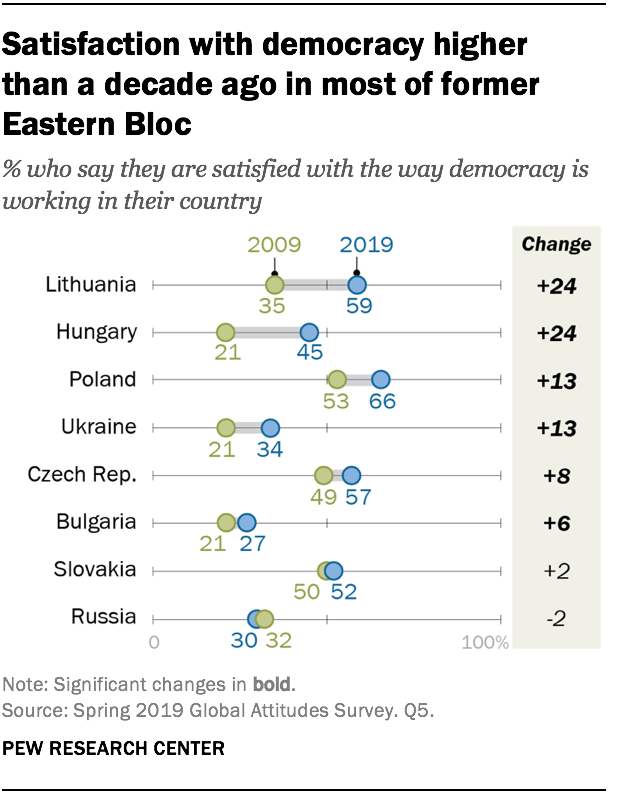

Across most of Central and Eastern Europe, satisfaction with democracy is significantly higher than a decade ago. Changes are most pronounced in Lithuania, where around six-in-ten are satisfied with democracy today, up from about a third (35%) in 2009. Similarly, in Hungary, more than twice as many are satisfied with democracy now (45%) than reported so a decade ago (21%). Satisfaction also increased over this time in Poland and Ukraine (+13 percentage points), the Czech Republic (+8 points) and Bulgaria (+6 points).

Across most of Central and Eastern Europe, satisfaction with democracy is significantly higher than a decade ago. Changes are most pronounced in Lithuania, where around six-in-ten are satisfied with democracy today, up from about a third (35%) in 2009. Similarly, in Hungary, more than twice as many are satisfied with democracy now (45%) than reported so a decade ago (21%). Satisfaction also increased over this time in Poland and Ukraine (+13 percentage points), the Czech Republic (+8 points) and Bulgaria (+6 points).

Elsewhere, even since last year, there have been some marked shifts in democratic satisfaction. For example, in Greece, although satisfaction remains relatively low overall (26%), it increased 9 percentage points since last year. In Spain, which had an election in April of this year, satisfaction with democracy has increased 12 points.

Elsewhere, satisfaction with democracy has declined. Since UK voters approved a referendum in 2016 to leave the European Union, satisfaction has dropped from 52% in 2017, to 42% in 2018, to the current 31%. In France, too, which was roiled by weeks of “yellow vest” protests, satisfaction with democracy has fallen, from 48% to 41% since 2018.

Across these and many other countries surveyed in prior years, those who express positive views of political parties that are in power tend to be more satisfied with democracy than those who have unfavorable views of those parties. (For more information on which parties are in power in the countries surveyed, see Appendix B.) For example, in France, 85% of those who support President Emmanuel Macron’s En Marche party are satisfied with democracy, compared with 34% of those who do not support it. Similarly, in the UK, Conservative Party supporters are more satisfied (44%) than those who are partisans of other parties (28%). The difference is largest in Hungary, where more than three-quarters of those who support Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s Fidesz Party are satisfied with democracy, compared with only around a quarter (26%) of those who do not.

Across these and many other countries surveyed in prior years, those who express positive views of political parties that are in power tend to be more satisfied with democracy than those who have unfavorable views of those parties. (For more information on which parties are in power in the countries surveyed, see Appendix B.) For example, in France, 85% of those who support President Emmanuel Macron’s En Marche party are satisfied with democracy, compared with 34% of those who do not support it. Similarly, in the UK, Conservative Party supporters are more satisfied (44%) than those who are partisans of other parties (28%). The difference is largest in Hungary, where more than three-quarters of those who support Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s Fidesz Party are satisfied with democracy, compared with only around a quarter (26%) of those who do not.

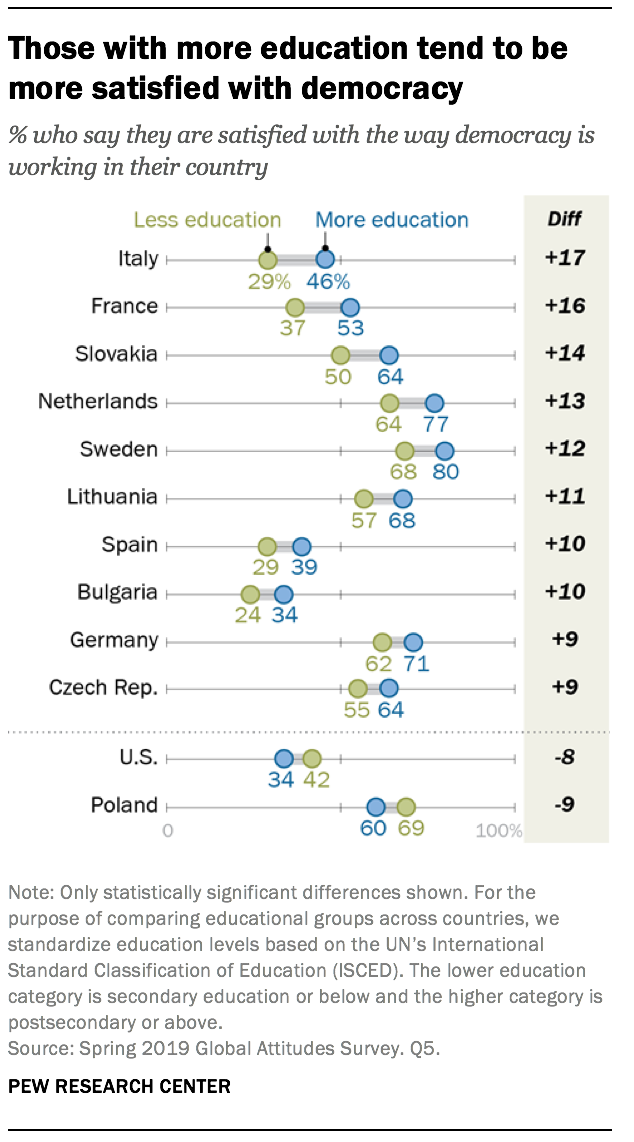

Across most of the countries surveyed, those with more education tend to be more satisfied with democracy than those with less education. For example, 37% of French with a secondary degree or less say they are satisfied with democracy, compared with roughly half (53%) of those with more schooling.

The United States and Poland stand out, though, for being the only countries surveyed where this pattern reverses. In the U.S., 42% of those with lower levels of education are satisfied with democracy, compared with 34% of those with higher levels.

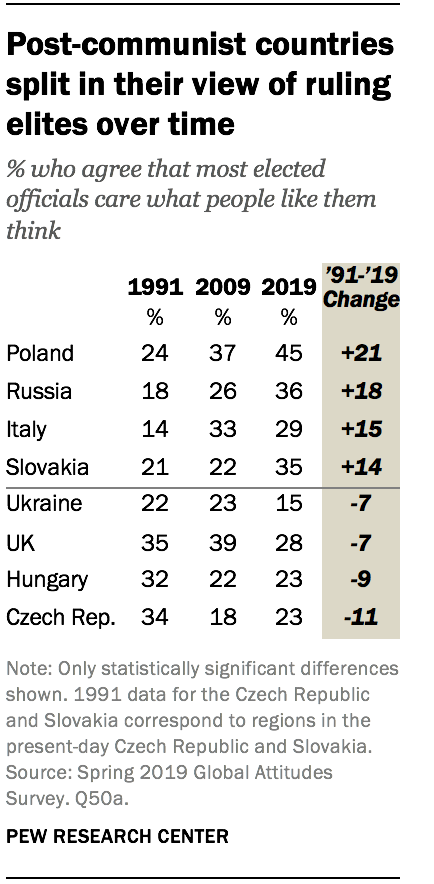

Few think elected officials care about people like them

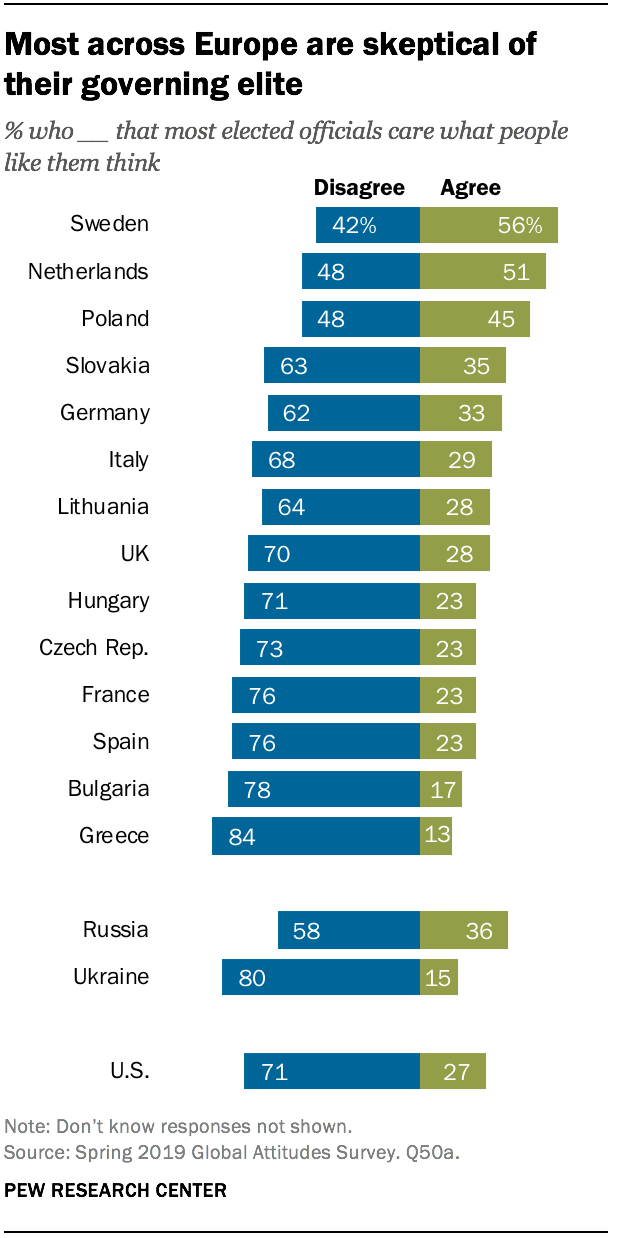

One factor that corresponds with democratic dissatisfaction and unites most EU nations – as well as the U.S., Russia and Ukraine – is a shared sense that elected officials do not care about their constituents. Only in Sweden does a majority say elected officials care what people like them think. The Dutch and Polish publics are roughly split on this question, but elsewhere majorities do not believe politicians care what they think. Greeks are the most negative when it comes to evaluations of their politicians: Only 13% say elected officials in their country care about people like them.

One factor that corresponds with democratic dissatisfaction and unites most EU nations – as well as the U.S., Russia and Ukraine – is a shared sense that elected officials do not care about their constituents. Only in Sweden does a majority say elected officials care what people like them think. The Dutch and Polish publics are roughly split on this question, but elsewhere majorities do not believe politicians care what they think. Greeks are the most negative when it comes to evaluations of their politicians: Only 13% say elected officials in their country care about people like them.

People with favorable views of six right-wing populist parties (Lega in Italy, PiS and Kukiz’15 in Poland, SNS in Slovakia, and Jobbik and Fidesz in Hungary) are more likely to agree that elected officials care what people like them think. For example, people with a favorable view of Fidesz in Hungary are more likely to say elected officials care (36%) than those who dislike the party (13%). But, among those with favorable opinions of the PVV and FvD in the Netherlands and the Sweden Democrats in Sweden, the opposite is true.

In post-communist countries, Poles, Russians and Slovaks have become more likely to say elected officials care about people like them since 1991. For example, 45% of Poles hold this view today, compared with 24% in 1991. In contrast, Czechs, Hungarians and Ukrainians are less likely now than in 1991 to see their politicians as caring about the ordinary person.

In post-communist countries, Poles, Russians and Slovaks have become more likely to say elected officials care about people like them since 1991. For example, 45% of Poles hold this view today, compared with 24% in 1991. In contrast, Czechs, Hungarians and Ukrainians are less likely now than in 1991 to see their politicians as caring about the ordinary person.

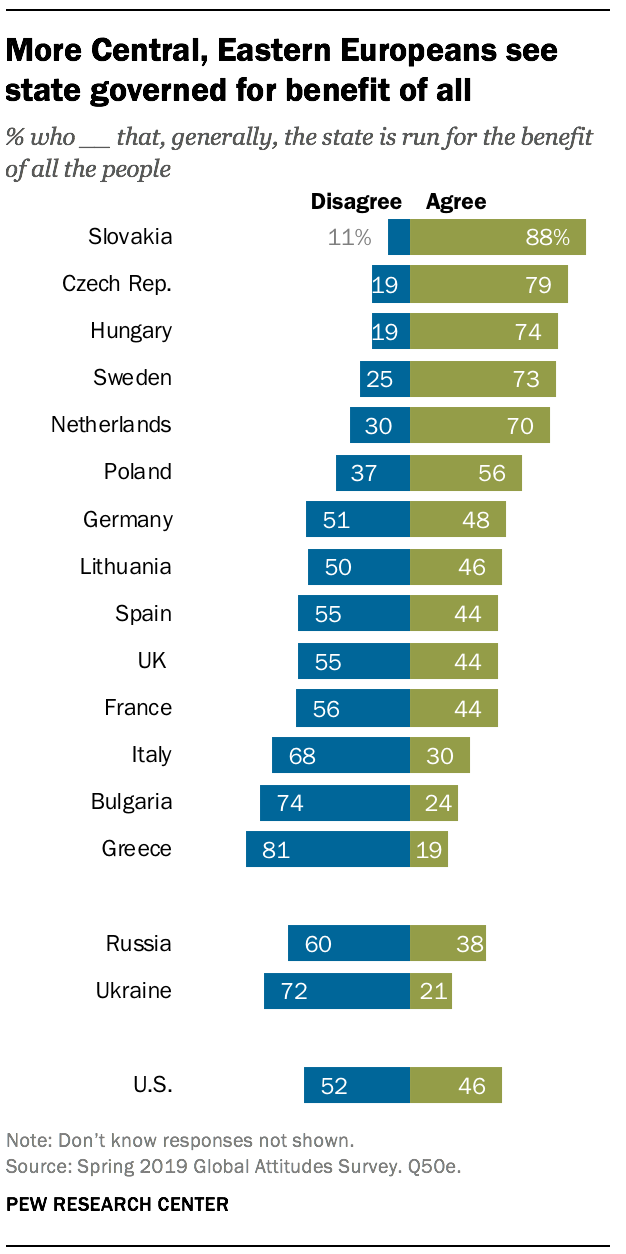

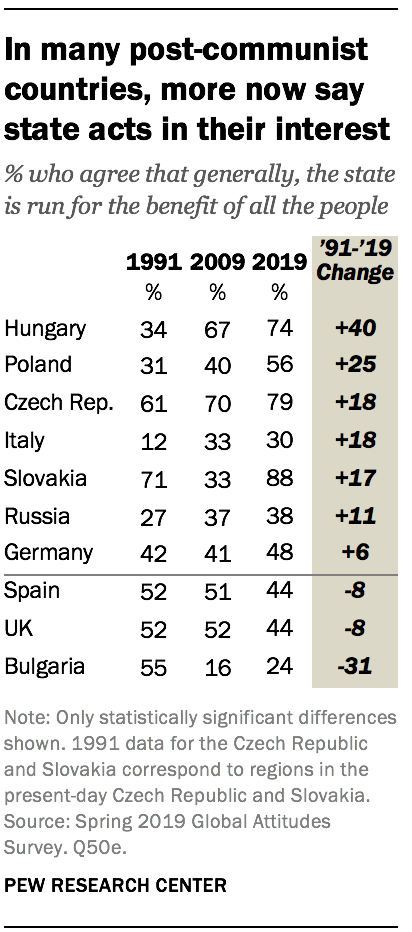

Europeans disagree about whether states are run for everyone’s benefit

While relatively united in their skepticism of elected officials, publics across Europe diverge in their assessments of whether the state is run for the benefit of all the people in the country. Generally, Central and Eastern Europeans stand out as more likely to agree than Western Europeans.

While relatively united in their skepticism of elected officials, publics across Europe diverge in their assessments of whether the state is run for the benefit of all the people in the country. Generally, Central and Eastern Europeans stand out as more likely to agree than Western Europeans.

But, within each region, there is substantial variation. For example, across Central and Eastern Europe, agreement ranges from a high of 88% in Slovakia to a low of 24% in Bulgaria. And, in Western Europe, northern countries tend to be relatively more sanguine – Sweden (73%) and the Netherlands (70%) in particular – and southern European countries more negative. The sense that the state benefits everyone is particularly low in Greece (19%) and Italy (30%). Similarly, in Ukraine (21%) and Russia (38%), only minorities agree that the state benefits everyone.

To the degree that opinions have shifted, many increasingly see benefits flowing to everyone. For example, in Hungary, whereas only around a third (34%) thought the state was run for the benefit of all in 1991, today, roughly three-quarters (74%) express this view. Change has also been positive and pronounced in Poland (+25 percentage points), the Czech Republic (+18 points) and Slovakia (+17 points). In Russia, agreement is up 11 percentage points. In Lithuania, while opinion is unchanged since 1991, it nonetheless is up markedly since a relative low point in 2009. Among Central and Eastern Europeans, only Bulgarians are significantly less likely to agree that the state is run for the benefit of all now than in 1991 (-31 points).

To the degree that opinions have shifted, many increasingly see benefits flowing to everyone. For example, in Hungary, whereas only around a third (34%) thought the state was run for the benefit of all in 1991, today, roughly three-quarters (74%) express this view. Change has also been positive and pronounced in Poland (+25 percentage points), the Czech Republic (+18 points) and Slovakia (+17 points). In Russia, agreement is up 11 percentage points. In Lithuania, while opinion is unchanged since 1991, it nonetheless is up markedly since a relative low point in 2009. Among Central and Eastern Europeans, only Bulgarians are significantly less likely to agree that the state is run for the benefit of all now than in 1991 (-31 points).

In Western Europe, opinion is more mixed. In Spain and the UK, fewer agree the state is run for the benefit of all now than in 1991. Germans and Italians, in contrast, are now more likely to agree.

With regard to right-wing populist sympathies, supporters are split. Those with favorable views of five right-wing populist parties – UKIP in the UK, PiS and Kukiz’15 in Poland, SNS in Slovakia and Fidesz in Hungary – are more likely to say the state is run for the benefit of all. For supporters of AfD in Germany, PVV and FvD in the Netherlands, Sweden Democrats in Sweden, and SPD in the Czech Republic, this pattern reverses.

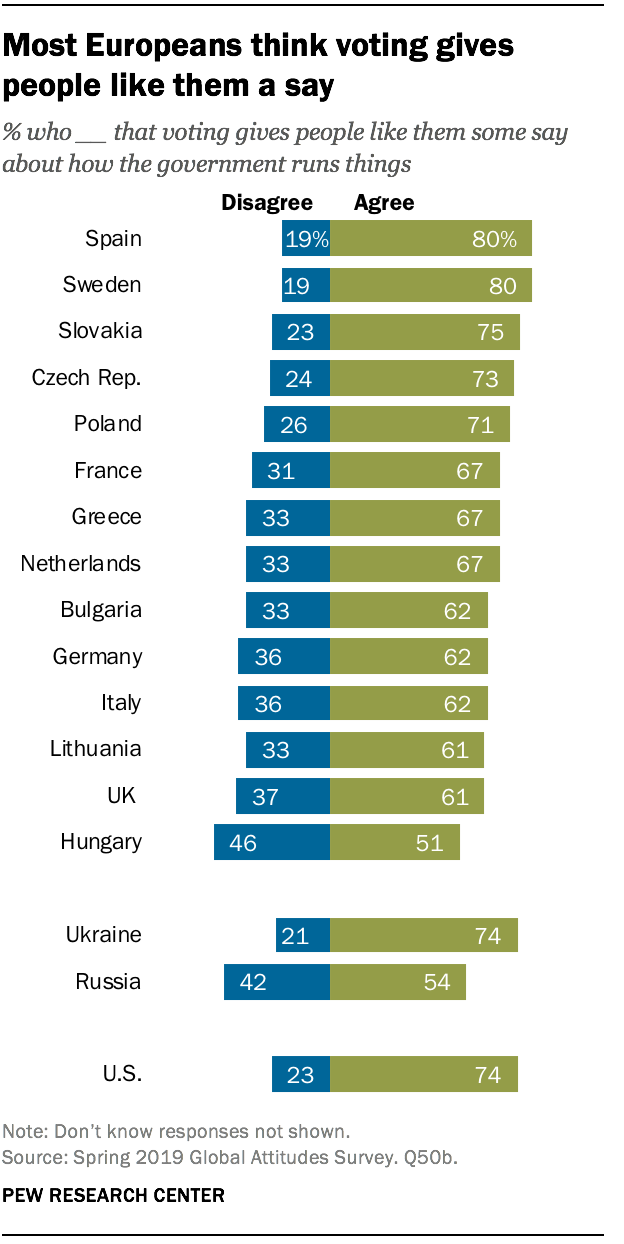

Most see value to voting

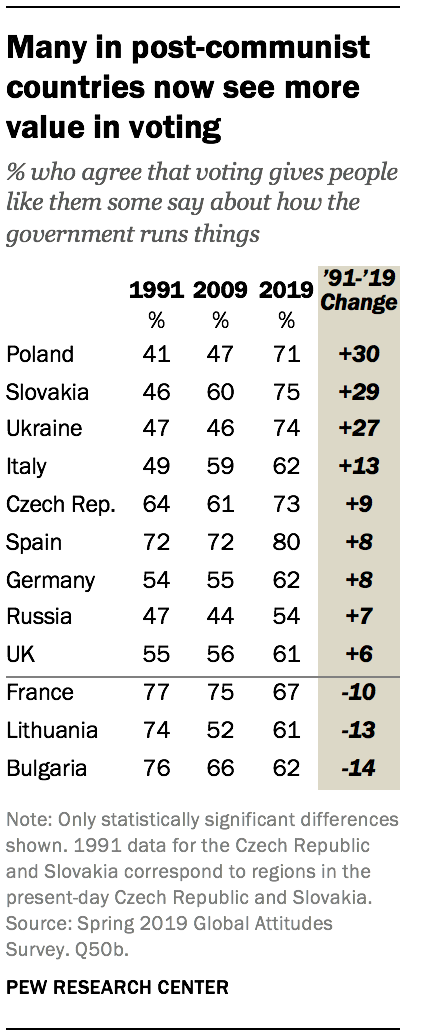

Despite mixed assessments about whether government is run for the benefit of all citizens, in every country surveyed, most people agree voting gives people like them some say in how the government runs things. A median of two-thirds in Europe generally think voting gives them a voice in their country’s politics, though levels of agreement range from a low of 51% in Hungary to a high of 80% in Spain and Sweden.

Despite mixed assessments about whether government is run for the benefit of all citizens, in every country surveyed, most people agree voting gives people like them some say in how the government runs things. A median of two-thirds in Europe generally think voting gives them a voice in their country’s politics, though levels of agreement range from a low of 51% in Hungary to a high of 80% in Spain and Sweden.

In most post-communist countries, people generally are more likely to agree today that voting affords them some influence than almost 30 years ago. Poles and Slovaks, for example, are around 30 percentage points more likely to say voting gives people like them a say than they were in 1991. Only in Lithuania and Bulgaria do fewer people say voting gives them a say now than said the same in 1991. In Russia and Ukraine, more now say voting gives them a voice – up 7 and 27 percentage points, respectively.

In most post-communist countries, people generally are more likely to agree today that voting affords them some influence than almost 30 years ago. Poles and Slovaks, for example, are around 30 percentage points more likely to say voting gives people like them a say than they were in 1991. Only in Lithuania and Bulgaria do fewer people say voting gives them a say now than said the same in 1991. In Russia and Ukraine, more now say voting gives them a voice – up 7 and 27 percentage points, respectively.

Across Western Europe, only the French are less likely to agree now that voting gives people like them a say than said the same in 1991, though most shifts in opinion have been relatively modest. For example, in Germany, whereas 54% agreed that voting gave them a say in 1991, today that number has climbed 8 percentage points to 62%.

Across most of the countries polled, people with higher levels of education are more likely to agree that voting allows them a say in their countries.

For supporters of five right-wing populist parties (AfD in Germany, PVV and FvD in the Netherlands, Vox in Spain and Sweden Democrats in Sweden), those who have favorable views of these right-wing populist parties are less likely to agree, though supporters of both populist parties in Poland, Fidesz supporters in Hungary and OLaNO-NOVA supporters in Slovakia stand apart as exceptions.