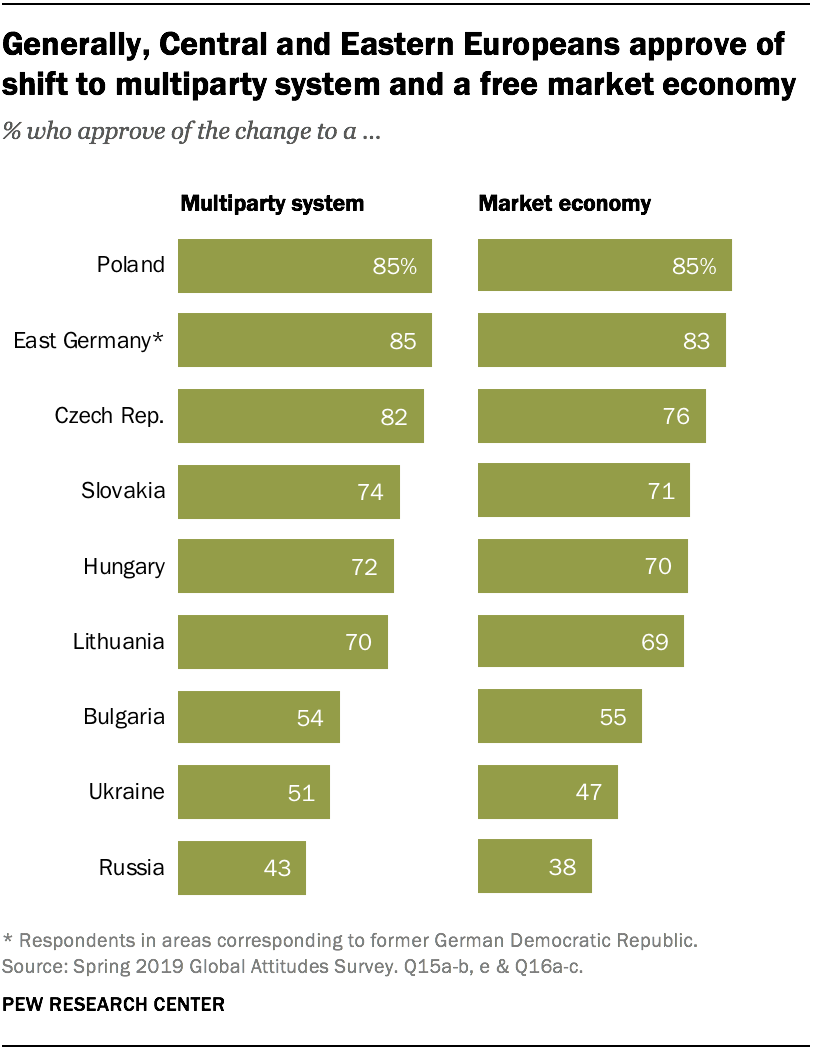

When asked about changes that have taken place since the end of the communist era, people across the former Eastern Bloc express support for the shift from one-party rule and a state-controlled economy to a multiparty system and a market economy. However, Russians in particular are less supportive of these changes.

When asked about changes that have taken place since the end of the communist era, people across the former Eastern Bloc express support for the shift from one-party rule and a state-controlled economy to a multiparty system and a market economy. However, Russians in particular are less supportive of these changes.

The move to a multiparty system garners the strongest approval from Poles (85%), those in former East Germany (85%) and Czechs (82%). But majorities in Slovakia, Hungary and Lithuania also approve. Roughly half or more in Bulgaria and Ukraine also support the change, even though there are more who disapprove in those countries. Only in Russia do fewer than half express support for the change to a multiparty system.

Support for the shift to a market economy is also robust in most of the countries surveyed, with majority support for the economic change found in many countries where majorities also favor the change to the political system. However, only 38% in Russia approve of the economic change, while 51% disapprove.

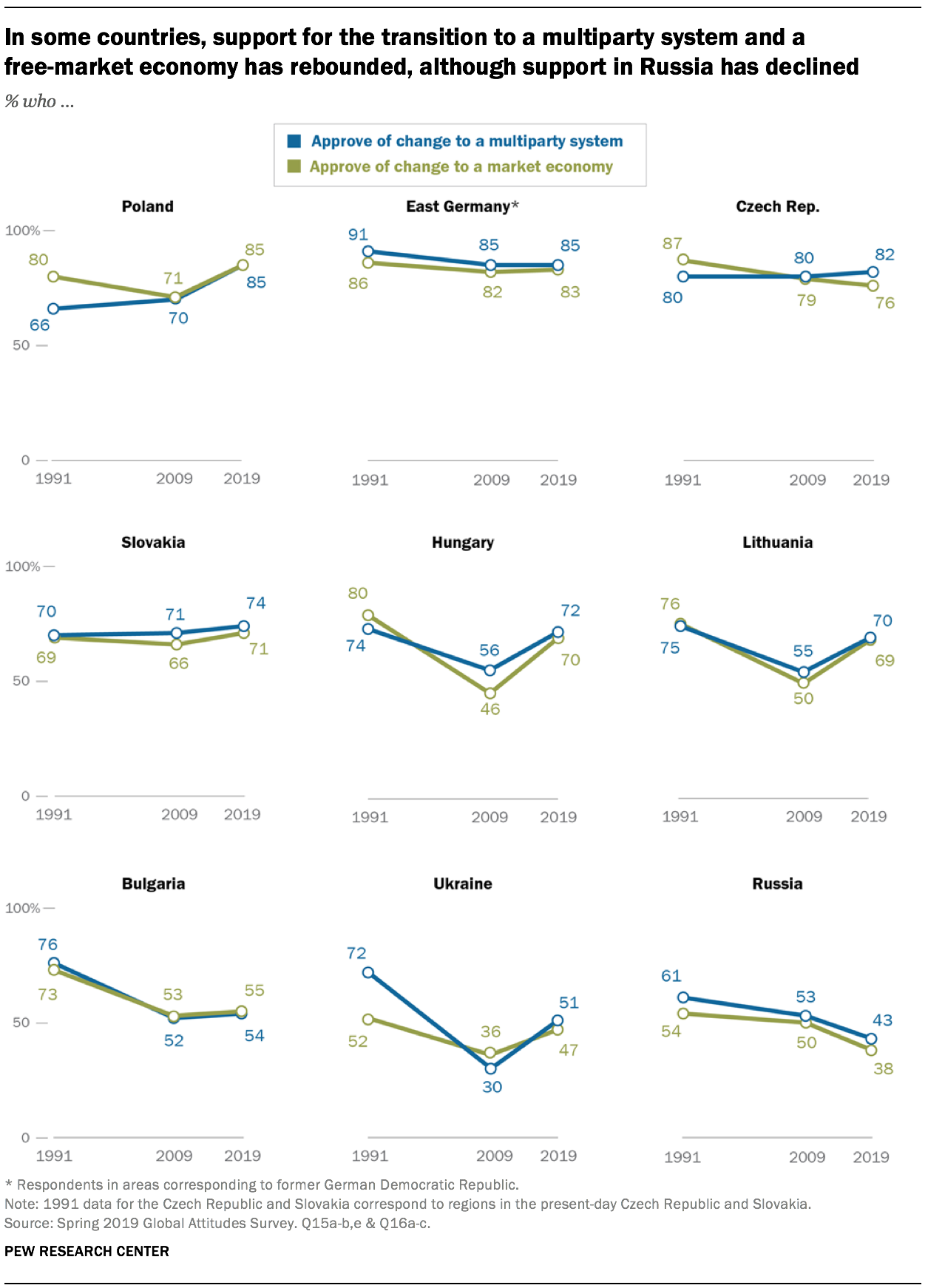

People in many of the countries surveyed are less supportive of the changes to the political and economic systems now than they were in 1991. However, since 2009, there has been a notable uptick in positive sentiment toward these changes in about half of the countries surveyed. Russia, a notable exception, is the only country where support has decreased since 2009.

For example, in Hungary, 74% in 1991 said they approved of the change to a multiparty system, and 80% liked the movement to a market economy. But when surveyed again in 2009, only 56% approved of the change to the political system since 1989 and 46% were positive on the change to the economic system. Now, however, 72% of Hungarians approve of the multiparty system and 70% like the capitalist system.

For example, in Hungary, 74% in 1991 said they approved of the change to a multiparty system, and 80% liked the movement to a market economy. But when surveyed again in 2009, only 56% approved of the change to the political system since 1989 and 46% were positive on the change to the economic system. Now, however, 72% of Hungarians approve of the multiparty system and 70% like the capitalist system.

Russians, however, are even more pessimistic than they were in in the past about these changes. In 1991, 61% of Russians welcomed the multiparty system, but that figure is 43% today, an 18 percentage point decline. And positive views toward the market economy are also down significantly since 1991.

Russians, however, are even more pessimistic than they were in in the past about these changes. In 1991, 61% of Russians welcomed the multiparty system, but that figure is 43% today, an 18 percentage point decline. And positive views toward the market economy are also down significantly since 1991.

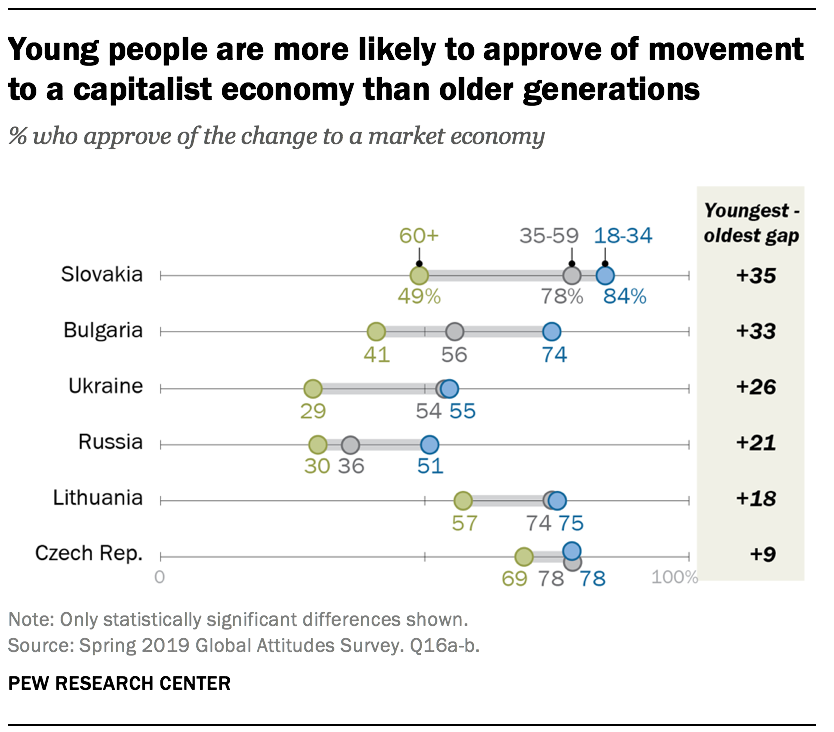

Young people in general are keener on the movement away from a state-controlled economy in many of the countries surveyed. For example, in Slovakia, 84% of 18- to 34-year-olds are in favor of this change, compared with 49% of those ages 60 and older. Double-digit age gaps also appear in Bulgaria, Ukraine, Russia and Lithuania.

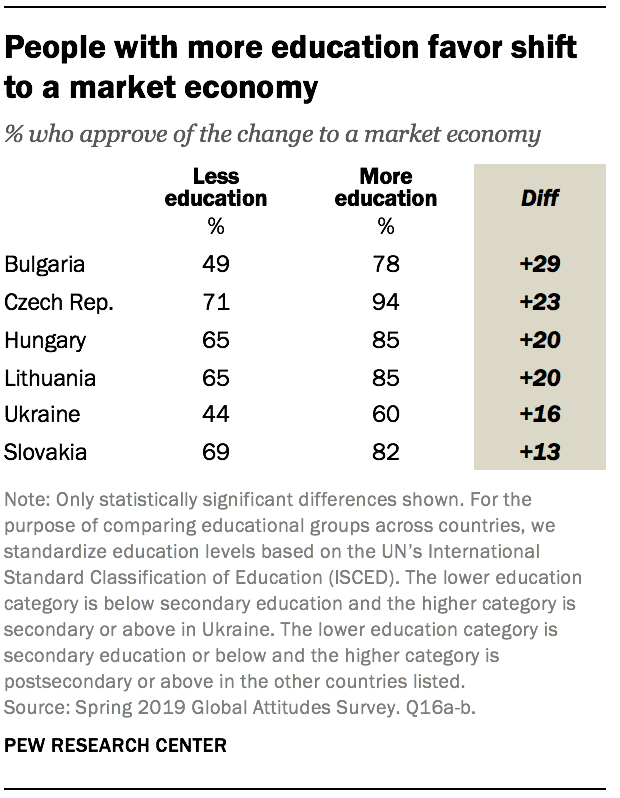

In most of the countries surveyed, those with more education are more likely to favor the movement to a capitalist economy than are those with less education. In Bulgaria, 78% of those with more than a secondary education favor the change to a capitalist economy, while only 49% of those with less education do. These differences are also significant for the change to a multiparty system.

In most of the countries surveyed, those with more education are more likely to favor the movement to a capitalist economy than are those with less education. In Bulgaria, 78% of those with more than a secondary education favor the change to a capitalist economy, while only 49% of those with less education do. These differences are also significant for the change to a multiparty system.

Similar differences appear when it comes to income, not just for the movement to a free-market economy but also for the change to a multiparty system. In all countries, those with incomes at or higher than the country median are more likely to approve of these changes than are those with incomes below the country medians.

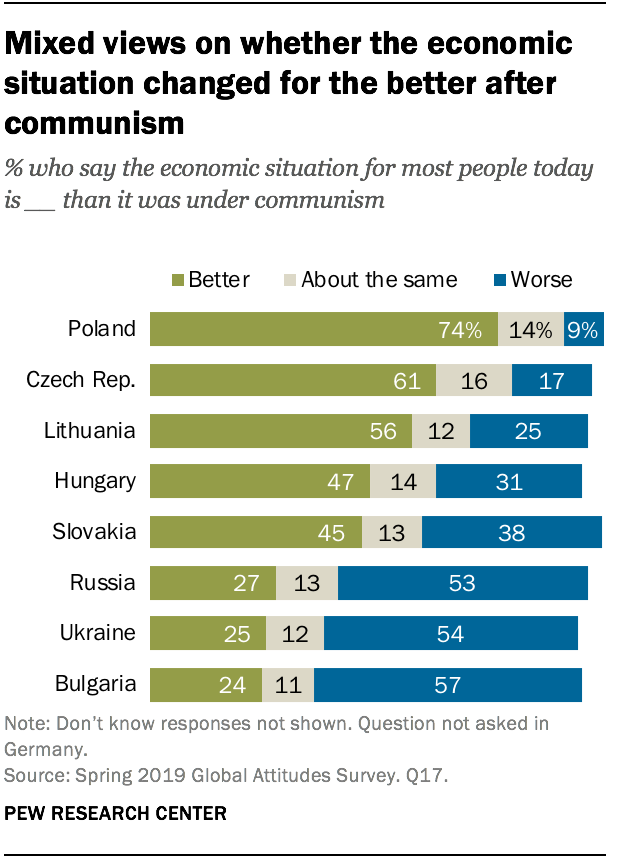

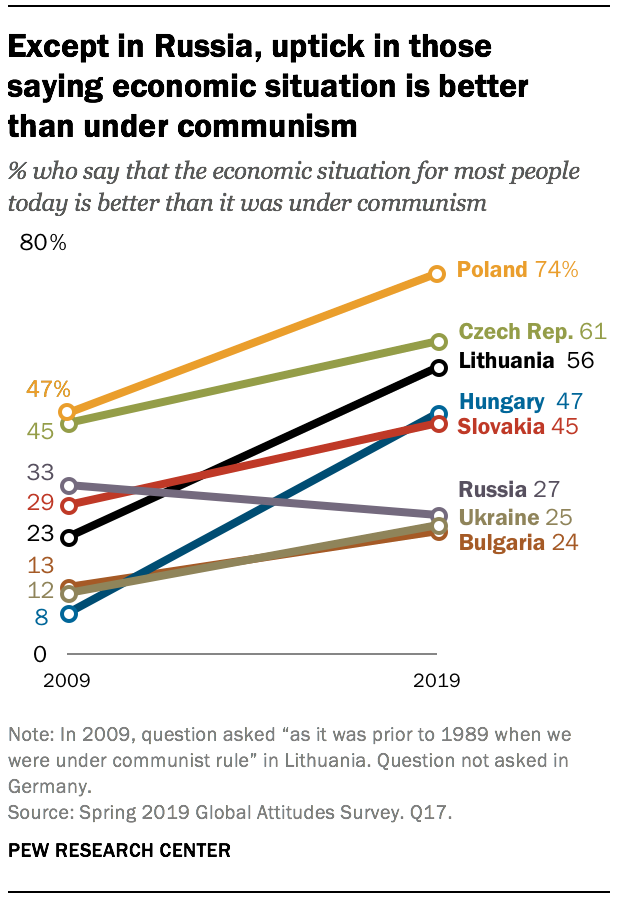

The transition from a state-controlled economy to a capitalist one is much more highly regarded now than in 2009, during the recession. Perhaps because of an improved economic outlook (see Chapter 5), many more now see the economic benefits of the new system compared with communism. However, there are sharp divides across countries on how the change affected most people.

The transition from a state-controlled economy to a capitalist one is much more highly regarded now than in 2009, during the recession. Perhaps because of an improved economic outlook (see Chapter 5), many more now see the economic benefits of the new system compared with communism. However, there are sharp divides across countries on how the change affected most people.

Despite no universal agreement on whether the economic situation is better today than it was under communism, the belief that it is better has become more common in every country since 2009, except Russia. In Poland, 47% held this view in 2009, but today that figure has jumped to 74%. However, in Russia fewer people now say the economic situation is better than under communism.

In Poland, the Czech Republic and Lithuania, majorities say the economic situation for most people is better today than it was under communism. In Hungary and Slovakia, more people say it is better, but substantial minorities still say it is worse. And in Bulgaria, Ukraine and Russia, more than half believe the economic situation is worse today than it was under communism. (This question was not asked in Germany.)

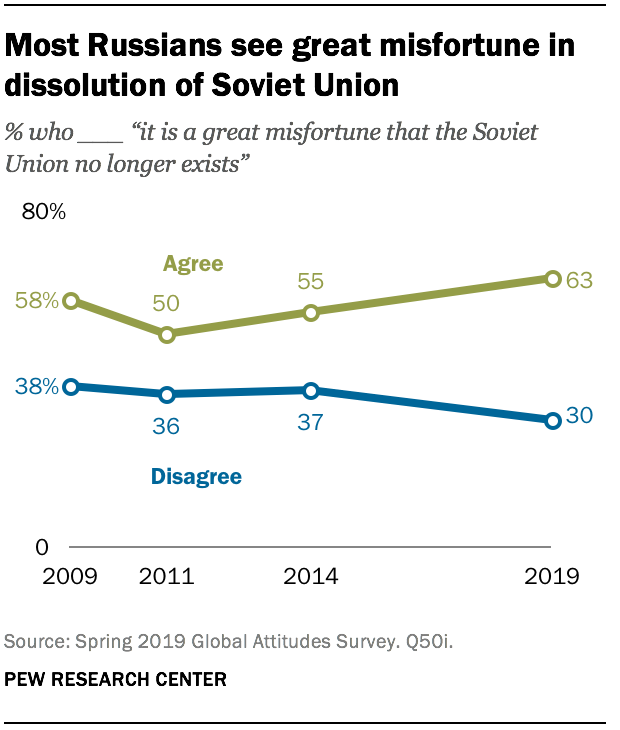

Most Russians characterize end of USSR as great misfortune

More than six-in-ten Russians agree with the statement “It is a great misfortune that the Soviet Union no longer exists.” This represents an increase of 13 percentage points since 2011. Only three-in-ten disagree with the statement.

More than six-in-ten Russians agree with the statement “It is a great misfortune that the Soviet Union no longer exists.” This represents an increase of 13 percentage points since 2011. Only three-in-ten disagree with the statement.

Russians who lived most of their lives under the Soviet Union are more likely to say its dissolution was a great misfortune than are those who grew up under the new system. Among Russians ages 60 and older, roughly seven-in-ten (71%) agree it is unfortunate that the USSR no longer exists, compared with half of Russians ages 18 to 34.

Germans view unification positively but feel the East has been left behind economically

Germans are in strong agreement that the 1990 unification of East and West was a good thing for Germany. Roughly nine-in-ten Germans, living in both the regions that correspond with the former West Germany and East Germany, agree with this statement.

However, when asked whether East and West Germany have achieved the same standard of living since unification, only three-in-ten Germans say this is the case.

Since 2009 there has not been much overall movement on this question in Germany as a whole. In former East Germany, however, people are about twice as likely now to say the standard of living is equal to that of the West than they were the last time this question was asked. Still, majorities of Germans from both regions say the East has not yet achieved equal economic footing with the West.

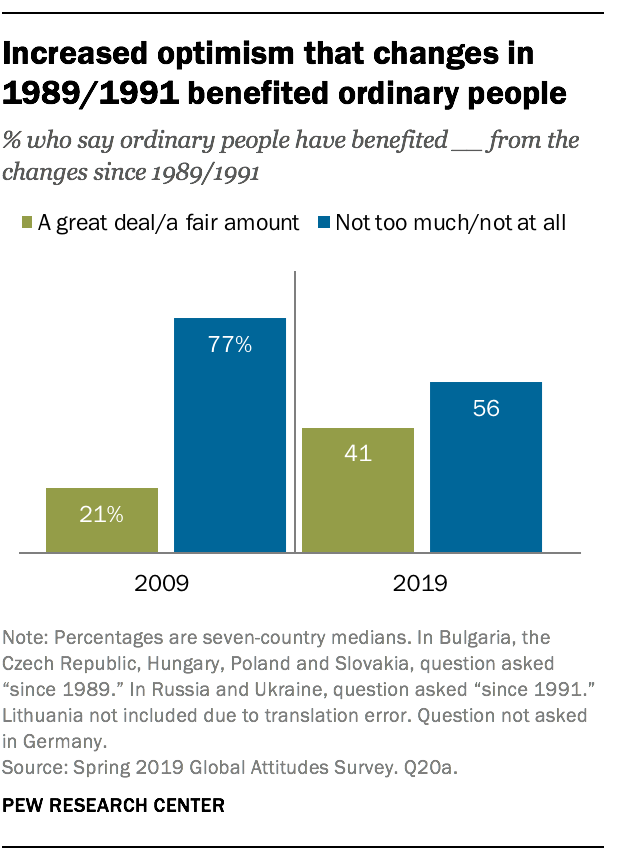

Politicians and business people seen as gaining from changes since the end of communism, more so than ordinary people

Majorities in all the former Soviet orbit countries surveyed say politicians and business people have benefited a great deal or fair amount since the fall of communism. And in all cases, more people say political and business leaders have prospered than say changes have benefited ordinary people.

People are especially inclined to believe politicians have benefited. Roughly nine-in-ten or more express this view in every nation where the question was asked, with the exception of Russia (still, 72% of Russians agree). Roughly three-quarters or more in every country also say business people have profited from the changes at least a fair amount, including 89% of those in the Czech Republic, Poland and Ukraine.

Publics are less inclined to believe ordinary people have been the beneficiaries of such changes. In Bulgaria, Ukraine and Russia, about one-in-five say this. On the other hand, nearly seven-in-ten Poles think ordinary people have prospered under the new system, as well as 54% of Czechs.

Nonetheless, more now say ordinary people have benefited than was the case 10 years ago. In 2009, a median of 21% across the seven countries surveyed said ordinary people were helped by the changes, while 77% said they were not. Now, a median of 41% across these same countries say ordinary people have benefited from the change, with 56% saying they have benefitted little or not at all.

Nonetheless, more now say ordinary people have benefited than was the case 10 years ago. In 2009, a median of 21% across the seven countries surveyed said ordinary people were helped by the changes, while 77% said they were not. Now, a median of 41% across these same countries say ordinary people have benefited from the change, with 56% saying they have benefitted little or not at all.

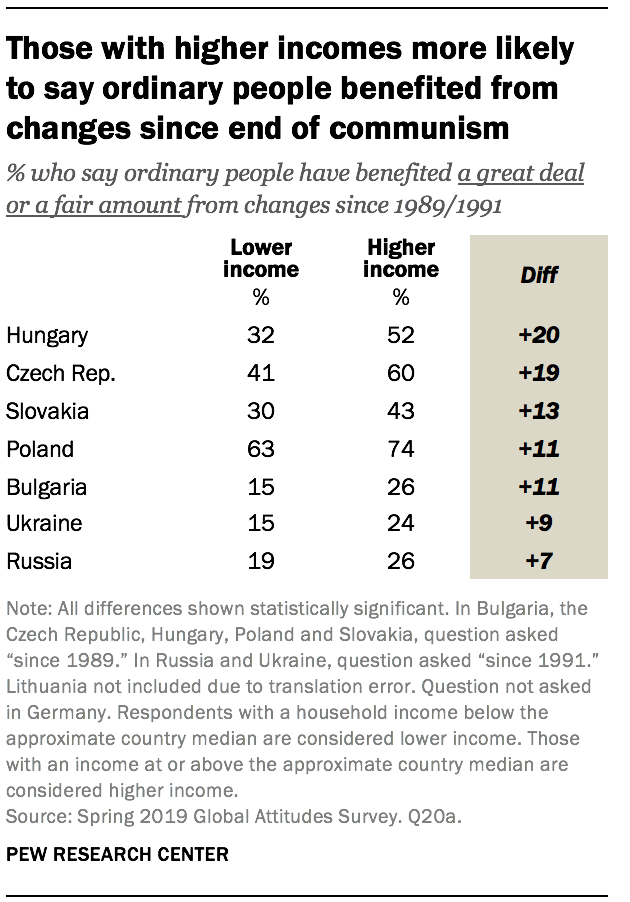

Within countries, there are divides on how people see average citizens making out in the change from communism to a free market. In every country where the question was asked, those with higher incomes are more likely than those with lower incomes to say the changes have benefited ordinary people. For example, in Hungary, those with an income at or above the national median are 20 percentage points more likely than those with lesser means to hold this view.

Education is also a dividing line on this question. In every country but Russia, those with more education are generally more likely to say regular people have prospered in the post-Soviet era than are those with less education.

Education is also a dividing line on this question. In every country but Russia, those with more education are generally more likely to say regular people have prospered in the post-Soviet era than are those with less education.

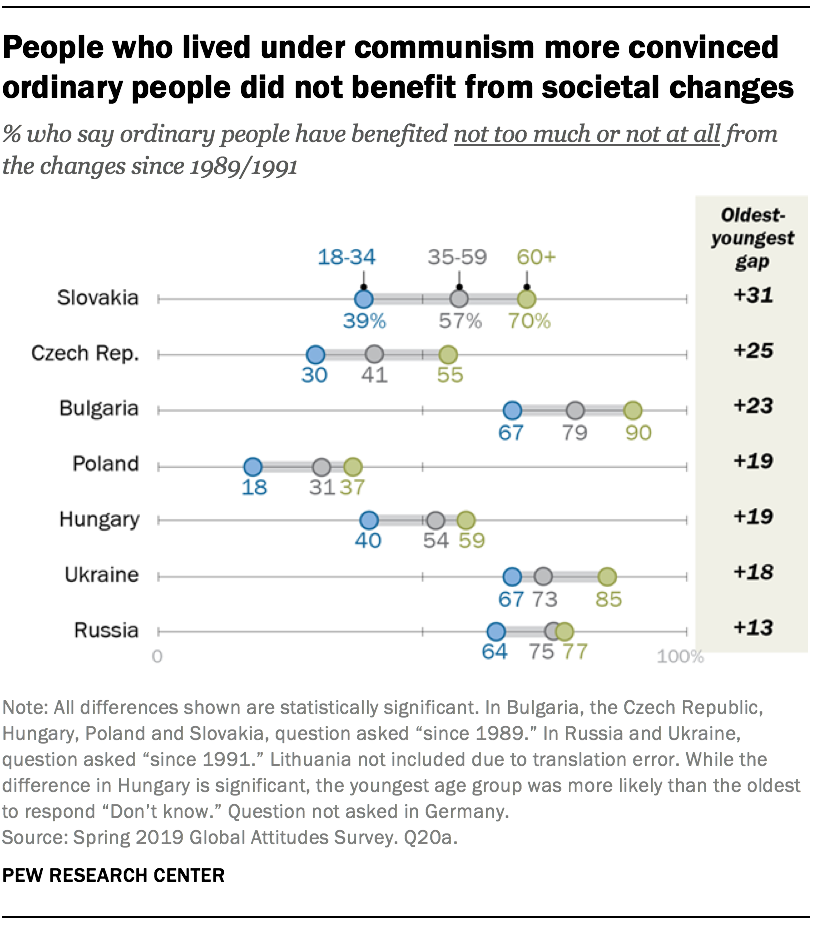

Additionally, those who lived through the communist era are much more likely to say the changes that took place have had not too much or no influence on ordinary people compared with those who were born near or after the changes took place. For example, in Slovakia, 70% of those ages 60 and older say ordinary people did not benefit from the change to capitalism and a multiparty system, compared with 39% who say this among 18- to 34-year-olds. Double-digit differences of this nature appear in every country surveyed, highlighting how those who lived through communism have a more negative view of the post-communist era.

Additionally, those who lived through the communist era are much more likely to say the changes that took place have had not too much or no influence on ordinary people compared with those who were born near or after the changes took place. For example, in Slovakia, 70% of those ages 60 and older say ordinary people did not benefit from the change to capitalism and a multiparty system, compared with 39% who say this among 18- to 34-year-olds. Double-digit differences of this nature appear in every country surveyed, highlighting how those who lived through communism have a more negative view of the post-communist era.

Central and Eastern Europeans say post-communist era has had both positive and negative effects on society

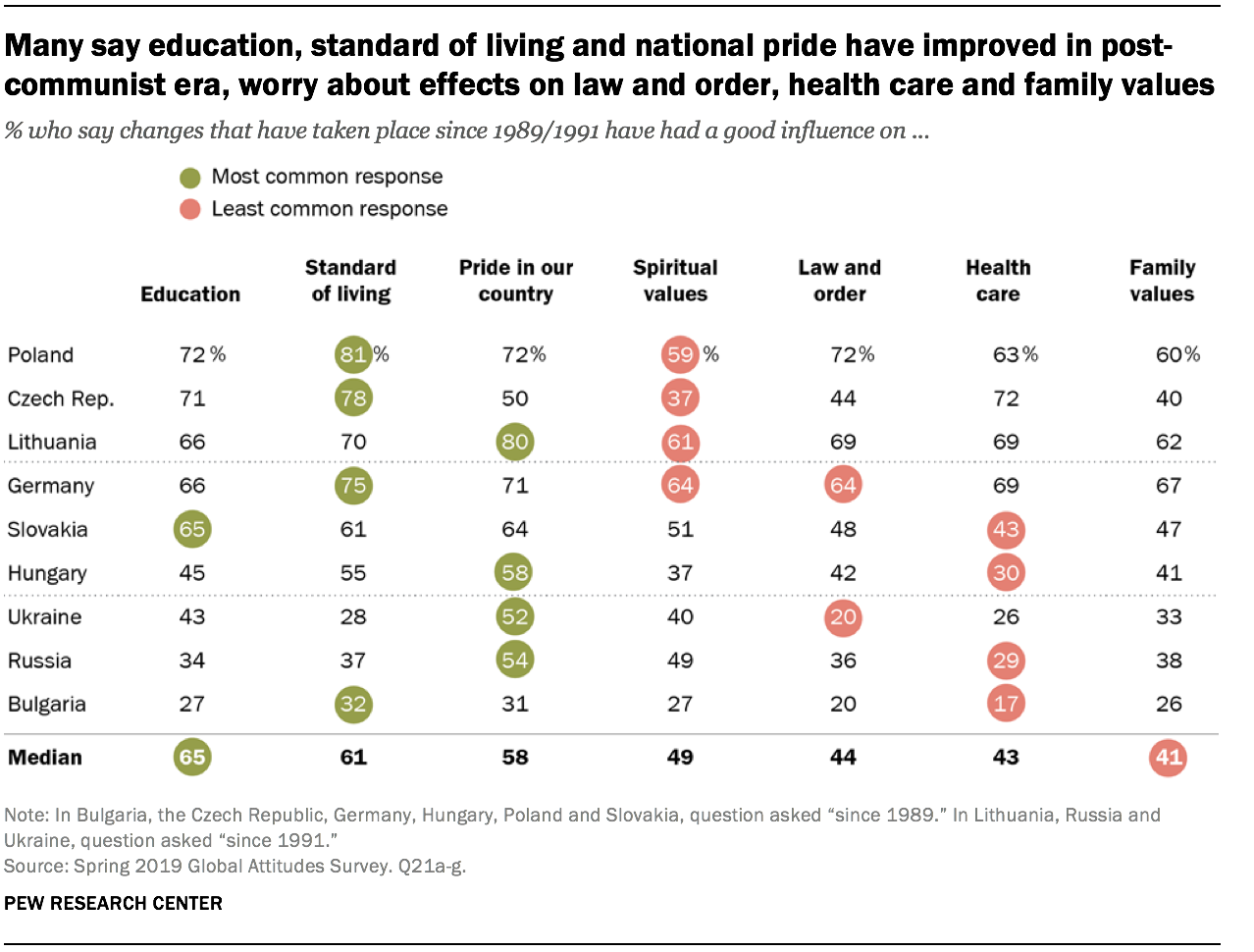

When asked whether the changes since 1989 and 1991 have benefited specific aspects of life in the post-communist era, people tend to believe education, the standard of living and pride in their country has improved. But they see downsides as well, and there are sharp differences between countries on the overall benefits of these changes.

For example, majorities of Poles, Lithuanians and Germans say the changes have had a good influence across every category asked, including education, standard of living, pride in their country, spiritual values, law and order, health care and family values. On the other end, roughly half or fewer Bulgarians, Ukrainians and Russians say the changes have had a good influence on these various issues, with the exception of the positive influence on pride in their country among Russians (54%) and Ukrainians (52%).

Sentiment is more mixed in Slovakia, the Czech Republic and Hungary, with people generally seeing the benefits of the changing standard of living and pride in their country. But worries persist about spiritual values in the Czech Republic and health care in Slovakia and Hungary.

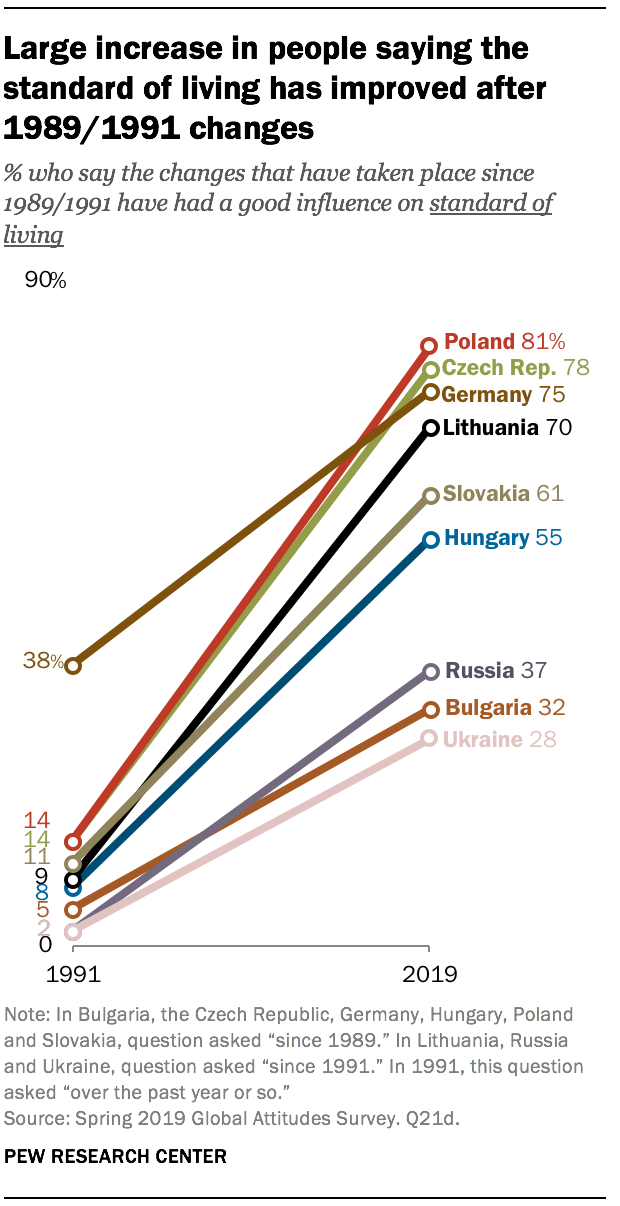

Since 1991, there have been significant increases in those in each survey country who say the changes taking place have had a good influence on various aspects of life. This is fairly consistent across countries and issues surveyed, but the degree of change varies from country to country and question to question.

Since 1991, there have been significant increases in those in each survey country who say the changes taking place have had a good influence on various aspects of life. This is fairly consistent across countries and issues surveyed, but the degree of change varies from country to country and question to question.

The most prominent increase is in the percentage of people who think the changes in 1989 and 1991 have had a good influence on the standard of living within each country. In many of the countries surveyed, there have been multifold increases in this sentiment from 1991 to today. For example, in Lithuania, only 9% of people in 1991 said that the recent changes had a positive influence on the standard of living for people in the country at the time. But in 2019, that figure has shot up to 70%, more than a sevenfold increase.

Large changes of this nature occurred in all the countries surveyed on this question from 1991 to 2019, even though there are still skeptics of the positive effect these changes have had on economic prosperity in Ukraine, Bulgaria and Russia.

On law and order, the changes are also more welcome now than in 1991 in every country surveyed. For example, 27% of Germans in 1991 said that recent events had had a positive influence on law and order in the country, compared with 64% who say this now.

And on pride in their country, there have been strikingly large increases in the share who believe changes have had a good influence in Russia and Ukraine. In 1991, around one-in ten said the changes to the political and economic systems were good for civic pride in Russia (9%) and Ukraine (11%), but now 54% and 52% say this, respectively.

The only instances where significantly fewer now say these changes have had a good influence on society for any of these various aspects tested are in the Czech Republic, Lithuania and Slovakia on spiritual values and in Lithuania on national pride.

On views of the standard of living, people with higher incomes and more education are more likely to say the changes since 1989 and 1991 have had a good influence in their countries. In Slovakia, those who have an income at or above the country median are 30 percentage points more likely to say the changes since 1989 have had a good influence on the standard of living compared with those who have a household income below the median. Significant differences of this nature appear in eight of the nine countries where this question was asked.

On views of the standard of living, people with higher incomes and more education are more likely to say the changes since 1989 and 1991 have had a good influence in their countries. In Slovakia, those who have an income at or above the country median are 30 percentage points more likely to say the changes since 1989 have had a good influence on the standard of living compared with those who have a household income below the median. Significant differences of this nature appear in eight of the nine countries where this question was asked.

A similar pattern applies for education. Those with more education are more likely than those with less to say the changes that have taken place since 1989 and 1991 had a good influence on standard of living in all countries besides Russia.

Young people are more likely to say the changes to a capitalist economy and a multiparty system have had a positive effect on health care in their country. In Slovakia, 56% of 18- to 34-year-olds say the societal changes had a good influence on the health care system, compared with only 27% of those ages 60 and older. Significant double-digit age gaps of this nature appear in seven of the nine countries where this question was asked.

Young people are more likely to say the changes to a capitalist economy and a multiparty system have had a positive effect on health care in their country. In Slovakia, 56% of 18- to 34-year-olds say the societal changes had a good influence on the health care system, compared with only 27% of those ages 60 and older. Significant double-digit age gaps of this nature appear in seven of the nine countries where this question was asked.

In Ukraine, those who only speak Ukrainian generally see a more positive influence of the societal changes on each issue than Russian-only speakers or those who speak both languages at home.

In Germany, there are many divides on whether the changes since 1989 have had a good influence on national conditions among those who currently live in the West versus those in the East, though overall sentiment in Germany toward these changes is quite positive.

In Germany, there are many divides on whether the changes since 1989 have had a good influence on national conditions among those who currently live in the West versus those in the East, though overall sentiment in Germany toward these changes is quite positive.

For example, those in the West are 20 percentage points more likely than those in the East to say the changes have had a good effect on the education system. Western Germans are also more likely to see the changes as a good influence on law and order and spiritual and family values compared with the East. However, there are no real differences of opinion between the West and East on how changes have benefited standard of living, health care and pride in their country.