About a quarter (27%) of Americans who have been employed for pay in the past two years, including those who are or were self-employed, report that they took time off from work during this period following the birth or adoption of their child, to care for a family member with a serious health condition, or to deal with their own serious condition. Some 6% have taken time off from work for more than one of these three reasons during this period.4

About a quarter (27%) of Americans who have been employed for pay in the past two years, including those who are or were self-employed, report that they took time off from work during this period following the birth or adoption of their child, to care for a family member with a serious health condition, or to deal with their own serious condition. Some 6% have taken time off from work for more than one of these three reasons during this period.4

The experiences of these leave takers, including the amount of time they took off, whether or not they received pay during that time, and how they coped with the loss of wages or salary if they didn’t vary considerably depending on factors such as their gender, educational attainment and household income.

For example, the survey finds that the median length of leave for mothers after the birth or adoption of a child is 11 weeks, compared with one week for fathers.5 Among mothers, those with household incomes of $75,000 or more and those with incomes between $30,000 and $74,999 tend to take more time off after birth or adoption than those with incomes below $30,000 (a median of 12 weeks and 10 weeks, respectively, for the higher and middle income groups vs. six weeks for mothers with lower incomes).

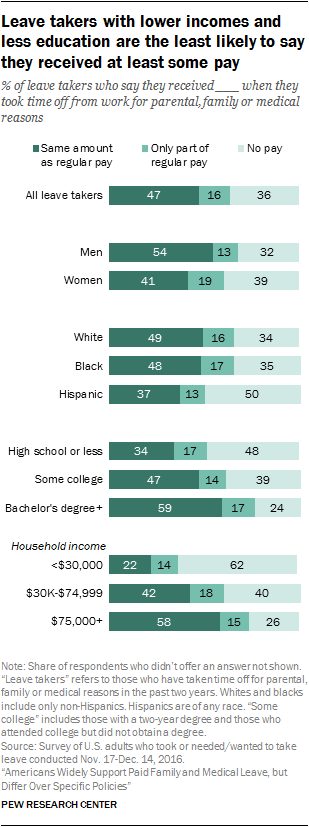

Overall, lower-income leave takers – including those who have taken time off from work for parental, family or medical reasons – are less likely than those with higher incomes to say they received at least some pay during their time off.6

In fact, about six-in-ten (62%) leave takers with household incomes under $30,000 say they received no pay at all, compared with 40% of those with incomes between $30,000 and $74,999 and even fewer (26%) among those with incomes of $75,000 or more.

Overall, lower-income leave takers – including those who have taken time off from work for parental, family or medical reasons – are less likely than those with higher incomes to say they received at least some pay during their time off.6

In fact, about six-in-ten (62%) leave takers with household incomes under $30,000 say they received no pay at all, compared with 40% of those with incomes between $30,000 and $74,999 and even fewer (26%) among those with incomes of $75,000 or more.

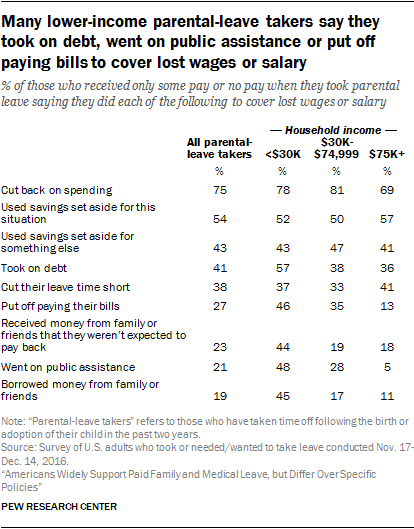

The survey findings reveal that the financial consequences of not receiving full pay during family or medical leave can be substantial for many workers. About eight-in-ten leave takers (78%) who say they received no pay or received only part of their regular pay when they took time off from work for parental, family or medical reasons say they cut back on spending to cover lost wages or salary during that time. A third or more say they used savings they had set aside for something else (50%), cut their leave time short (41%), took on debt (37%) or put off paying their bills (33%); about a quarter say they borrowed money from family or friends (24%) or received money from family or friends they weren’t expected to pay back (23%), and 17% went on public assistance.

Lower-income leave takers – especially those who took parental leave – are particularly likely to say they had to resort to more consequential measures to make up for the loss of income during their time off. About six-in-ten parental-leave takers (57%) with household incomes under $30,000 who did not receive their full pay during their leave say they took on debt, while roughly half say they went on public assistance (48%) or put off paying bills (46%).

The survey also explores the experiences of those who say there was a time in the past two years when they needed or wanted to take time off from work following the birth or adoption of a child, to care for a family member with a serious health condition, or to deal with their own serious condition but were unable to do so for some reason. About one-in-six (16%) American adults who were employed in the past two years say this happened to them during this time, and the share is higher among women as well as among blacks and Hispanics, those without a bachelor’s degree and those with annual household incomes under $30,000.

For example, about a quarter of blacks (26%) and Hispanics (23%) who were employed in the past two years report that there was a time during this period when they needed or wanted to take time off from work but were not able to do so; 13% of employed whites say this happened to them. Similarly, three-in-ten workers with annual household incomes under $30,000 say they had this experience in the past two years, compared with 17% of those with incomes between $30,000 and $74,999 and 12% of those with incomes of $75,000 or more.

The reasons some people aren’t able to take time off from work when these situations arise vary, but most (72%) say they couldn’t afford to lose wages or salary. Just over half (54%) of those who didn’t take leave when they needed or wanted to say they didn’t take time off from work because they thought they might risk losing their job, a concern that is particularly common among lower-income workers. In addition, 42% of workers who needed or wanted to take leave but were unable to do so say they felt badly about co-workers taking on additional work, 40% thought taking time off might hurt their chances for advancement, 36% felt no one else was capable of doing their job, and 32% had their request for time off denied by their employer.

About seven-in-ten fathers say they took two weeks or less off from work following the birth or adoption of their child

The amount of time workers take off from their jobs for parental, family or medical reasons differs depending on the situation. For example, among those who have taken time off from work in the past two years following the birth or adoption of their child, the median length of leave was 4.3 weeks. For those who took time off from work to care for a family member with a serious health condition in the past two years, the median length of leave was two weeks, similar to the median amount of leave taken by those who were dealing with their own serious health condition (2.1 weeks).

The amount of time workers take off from their jobs for parental, family or medical reasons differs depending on the situation. For example, among those who have taken time off from work in the past two years following the birth or adoption of their child, the median length of leave was 4.3 weeks. For those who took time off from work to care for a family member with a serious health condition in the past two years, the median length of leave was two weeks, similar to the median amount of leave taken by those who were dealing with their own serious health condition (2.1 weeks).

Mothers take much longer leaves than fathers: a median of 11 weeks for mothers vs. one week for fathers. In fact, about seven-in-ten fathers (72%) say they took two weeks or less off from work following the birth or adoption of their child. In contrast, about half (47%) of mothers who took time off from work in the past two years following birth or adoption say they were off for 12 weeks or more. Still, 17% of women say they returned to work less than six weeks after the birth or adoption of their child.

Women with lower household incomes generally take far shorter leaves than those with higher incomes. The median length of leave was 12 weeks for mothers with household incomes of $75,000 or more and 10 weeks for those with incomes between $30,000 and $74,999. In contrast, the median length of leave for mothers with household incomes under $30,000 was six weeks.

Among all parents who took time off from work following the birth of adoption of their child in the past two years, those who were employed by government or by a nonprofit organization generally took longer leaves than those who were employed by a private, for-profit company (median of six weeks for those in government or in nonprofits vs. three weeks for those in for-profit companies).7

For the most part, parents take time off from work all at once following the birth or adoption of their child; 78% say they did this, compared with 16% who say they took time off in separate blocks or as needed. Fathers (22%) are more likely than mothers (9%) to say they took time off in separate blocks or as needed following the birth or adoption of their child.

Among those who took time off from work to care for a family member with a serious health condition in the past two years, 15% took at least six weeks off, and this is more common among women than among men who have taken time off to care for a seriously ill family member (19% vs. 11%). Regardless of the number of weeks they took off, about half (48%) say they took this time off all at once, while about as many (49%) took it in separate blocks or as needed.

Older workers typically take longer leaves than younger workers to deal with their own serious health conditions. Roughly a third (36%) of workers ages 50 and older who took time off for this reason say they were off for at least six weeks, compared with 27% of those 30 to 49 and 23% of those younger than 30. About two-thirds (68%) of those who have taken time off to deal with their own serious health condition took the time off all at once, while 29% say they took it in blocks or as needed.

For many parents, amount of time off after birth or adoption of a child wasn’t enough

Among those who took time off from work following the birth or adoption of their child, 56% say they took less time off than they needed or wanted to, while 36% say they took about as much time off as they needed or wanted to and 7% say they took more time than they needed or wanted.

Compared with those who took time off for parental reasons, workers who took time off to care for a family member with a serious health condition or to deal with their own serious condition are more satisfied with the amount of time they spent away from their jobs. About half (50% of those who took leave to care for an ill family member and 55% who took leave because of their own medical condition) say they took about as much time off as they needed or wanted, while close to four-in-ten say they wish they had taken more time off than they did. One-in-ten of those who took time off from work to care for an ill family member and 5% of those who were dealing with their own serious health condition say they took more time off than they needed or wanted to.

Compared with those who took time off for parental reasons, workers who took time off to care for a family member with a serious health condition or to deal with their own serious condition are more satisfied with the amount of time they spent away from their jobs. About half (50% of those who took leave to care for an ill family member and 55% who took leave because of their own medical condition) say they took about as much time off as they needed or wanted, while close to four-in-ten say they wish they had taken more time off than they did. One-in-ten of those who took time off from work to care for an ill family member and 5% of those who were dealing with their own serious health condition say they took more time off than they needed or wanted to.

Mothers and fathers, as well as parents across racial, educational and income groups, give similar assessments of the amount of time they took off from work following the birth or adoption of their child. For example, about six-in-ten fathers who took time off from work (59%) say they took less time off than they needed or wanted to, while 5% say they took more time off and 35% say they took about as much time off as they needed or wanted to. Among mothers, 53% wish they had taken more time off, while 10% say they took more time off than they needed or wanted to; 37% said they took about the right amount of time off.

There is a significant income gap in satisfaction with the amount of time taken off among workers who took leave to care for an ill family member or to deal with their own health problem. Among those who took time off from work in the past two years to care for a family member with a serious health condition, six-in-ten workers with annual household incomes of $75,000 or more say they took as much time off as they needed or wanted to. By comparison, only about four-in-ten of those with incomes below $75,000 say the same.

Those with lower incomes who took time off to deal with their own serious health condition are also less likely than those with higher incomes to say they took as much time off as they needed or wanted to. About four-in-ten (42%) of those with household incomes under $30,000 say this is the case, while about as many (47%) say they took less time off than they needed or wanted to. Among those with household incomes of $75,000 or more, six-in-ten say they took as much time off as they needed or wanted (35% say they wish they had taken more time off).

Concerns about loss of wages or salary top the list of reasons why some take less time off than they need or want to

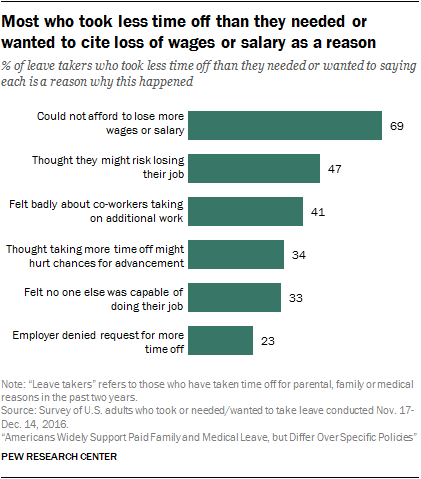

When those who say they took less time off from work than they needed or wanted to following birth or adoption of their child, to care for a family member with a serious health condition or to deal with their own serious condition are asked why they did not take more time off, financial concerns top the list of reasons. About seven-in-ten (69%) say they could not afford to lose more wages or salary.

When those who say they took less time off from work than they needed or wanted to following birth or adoption of their child, to care for a family member with a serious health condition or to deal with their own serious condition are asked why they did not take more time off, financial concerns top the list of reasons. About seven-in-ten (69%) say they could not afford to lose more wages or salary.

Nearly half (47%) of leave takers who took less time off from work than they needed or wanted to say they thought they might risk losing their job if they took more time off, while 41% say they felt badly about co-workers taking on additional work. About a third thought taking more time off might hurt their chances for job advancement (34%) or felt that no one else was capable of doing their job (33%). Roughly a quarter (23%) of those who took less time off than they needed or wanted to say their employer denied their request for more time off.

Across income levels, majorities of leave takers who say they took less time off from work than they needed or wanted to cite loss of wages or salary as a reason. But while most (63%) of those with household incomes below $30,000 say they thought they might risk losing their job if they took more time off, middle- and higher-income workers are much less likely to point to this as a factor (47% among those with incomes between $30,000 and $74,999 and 42% among those earning $75,000 or more). Differences across income groups are not as pronounced on any of the other items.

Those who say there was a time in the past two years when they needed or wanted to take time off from work but were not able to do so also point to financial and career concerns as reasons why they didn’t take time off. About seven-in-ten (72%) say not being able to afford to lose wages or salary was a reason why they didn’t take time off. About half thought they might risk losing their job (54%), while about four-in-ten say they felt badly about their co-workers taking on additional work (42%) or worried that taking time off might hurt their chances for job advancement (40%); 36% of those who did not take leave when they needed or wanted to felt no one else was capable of doing their job and 32% say their request for time off was denied.

Lower-income, less-educated workers are the least likely to receive pay when taking time off for parental, family or medical reasons

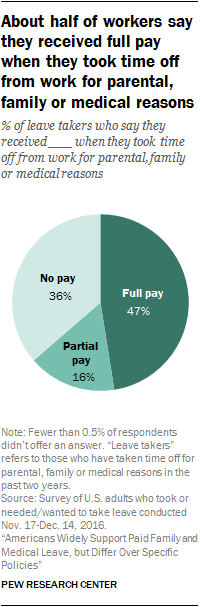

A majority of Americans who took time off from work in the past two years for parental, family or medical reasons say they received at least some pay during this time, including 47% who received the same amount as their regular pay and 16% who received only part of their regular pay; 36% of leave takers received no pay.

Experiences vary dramatically by income. A majority (62%) of leave takers with household incomes under $30,000 say they received no pay when they took time off from work for parental, family or medical reasons. In contrast, six-in-ten leave takers with household incomes between $30,000 and $74,999 (60%) and an even higher share (74%) of those with incomes of $75,000 or more say they received at least some pay, including 42% of those in the middle income group and 58% of those in the higher income group who say they received full pay during the time they were off from work.

The pattern is similar when it comes to educational attainment. About six-in-ten (59%) leave takers with a bachelor’s degree or more education say they received full pay during their time off from work, compared with 47% of those with some college experience and even fewer (34%) among those with a high school education or less. Roughly half (48%) of those with a high school diploma or less received no pay during their parental, family or medical leave.

Fathers are far more likely than mothers to say they received the same as their regular pay when they took time off from work following the birth or adoption of their child: 62% of fathers say this, compared with only a quarter of mothers. This may be, at least in part, because fathers report having taken considerably less time off from work than mothers. Seven-in-ten fathers and six-in-ten mothers say they received at least some pay during their time off from work. Men and women who took time off in the past two years to care for a family member with a serious health condition or to deal with their own serious condition are about equally likely to say they received pay, including similar shares who say they were paid the same as their regular pay.

Fathers are far more likely than mothers to say they received the same as their regular pay when they took time off from work following the birth or adoption of their child: 62% of fathers say this, compared with only a quarter of mothers. This may be, at least in part, because fathers report having taken considerably less time off from work than mothers. Seven-in-ten fathers and six-in-ten mothers say they received at least some pay during their time off from work. Men and women who took time off in the past two years to care for a family member with a serious health condition or to deal with their own serious condition are about equally likely to say they received pay, including similar shares who say they were paid the same as their regular pay.

Among all leave takers who received only part of their regular pay, a majority say it was difficult for them to have enough money to cover their basic expenses during their time off from work (41% say it was somewhat difficult, 18% say it was very difficult). This is particularly the case for those who took leave to care for a family member with a serious health condition (65% say it was difficult to cover basic expenses) or to deal with their own serious health condition (64%). About half (49%) of those who took time off from work following the birth or adoption of their child and received only part of their regular pay say it was hard for them to cover their basic expenses during their leave.

Leave takers with annual household incomes under $30,000 (75%) and those with incomes between $30,000 and $74,999 (63%) are more likely than those with higher incomes to say it was difficult for them to cover their basic expenses when they were receiving only part of their pay. But even among those with incomes of $75,000 or more, half say this was the case.

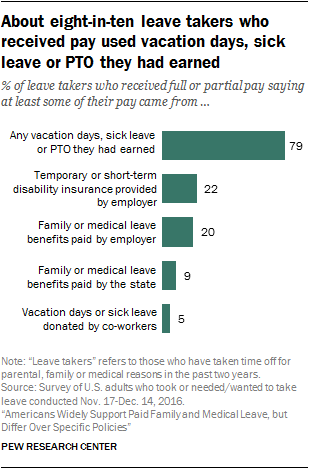

About eight-in-ten used vacation days or sick leave in order to receive pay; about one-in-five had employer-paid leave separate from vacation or sick leave

About eight-in-ten Americans (79%) who received at least some pay when they took time off from work in the past two years for parental, family or medical reasons report that at least part of their pay came from vacation, sick leave or paid time off (PTO) they had earned. Roughly one-in-five say at least some of the pay they received was part of temporary or short-term disability insurance provided by their employer (22%) or part of family or medical leave benefits paid by their employer (20%). Relatively few say they received pay from family or medical leave benefits paid by their state (9%) or from vacation days or sick leave donated to them by their co-workers (5%).

About eight-in-ten Americans (79%) who received at least some pay when they took time off from work in the past two years for parental, family or medical reasons report that at least part of their pay came from vacation, sick leave or paid time off (PTO) they had earned. Roughly one-in-five say at least some of the pay they received was part of temporary or short-term disability insurance provided by their employer (22%) or part of family or medical leave benefits paid by their employer (20%). Relatively few say they received pay from family or medical leave benefits paid by their state (9%) or from vacation days or sick leave donated to them by their co-workers (5%).

Among those who received pay when they took time off from work following the birth or adoption of their child, an equal share of mothers (76%) and fathers (74%) say at least part of their pay came from vacation, sick leave or PTO they had earned. But mothers are far more likely than fathers to report that at least some of the pay they received was part of temporary or short-term disability (50% vs. 10%), family or medical leave paid by their employer (35% vs. 23%), and family or medical leave paid by the state (23% vs. 7%).

Those who took paid time off from work following the birth or adoption of their child are more likely than those who took paid time off to care for a family member with a serious health condition or to deal with their own serious condition to say they received at least some pay as part of family or medical leave benefits paid by their employer, separate from vacation, sick leave or PTO (28% vs. 15% and 17%, respectively).

Leave takers who were employed by a private, for-profit company are somewhat more likely than those who were employed by government or by a nonprofit organization to say at least some of their pay was part of family or medical leave benefits paid by their employer (22% vs. 15%).

Leave takers who were employed by a private, for-profit company are somewhat more likely than those who were employed by government or by a nonprofit organization to say at least some of their pay was part of family or medical leave benefits paid by their employer (22% vs. 15%).

Leave takers who received pay when they took time off from work for parental, family or medical reasons in the past two years report that they often needed to combine various benefits in order to cover their wages or salary during their leave. Most leave takers who received pay (62%) say their pay came from only one source. Still, about three-in-ten (29%) say their pay came from two or more benefits.

Mothers who received pay when they were on leave from work following the birth or adoption of their child are the most likely to report that their pay was part of two or more benefits (60% vs. 22% of fathers who received pay when they took time off for the same reason). This reflects, at least in part, the fact that mothers tend to take more time off from work than fathers, which may require tapping into additional benefits in order to receive pay.

Among those who say there was a time in the past two years when they needed or wanted to take time off from work for parental, family or medical reasons but were not able to do so, half say they had access to paid vacation, sick leave or PTO at the time; 26% say they had access to temporary or short-term disability insurance provided by their employer; 21% say they had access to family or medical leave benefits paid by their employer; and 14% say they had access to family or medical leave benefits paid by the state.

Among workers who weren’t able to take time off when they needed or wanted to, those with household incomes of $75,000 or more are far more likely than those with lower incomes to say they had access to vacation, sick leave or PTO at the time. Six-in-ten in the higher income group say this, compared with 49% of those with household incomes between $30,000 and $74,000 and just 29% of those with incomes under $30,000. And while about a third (34%) of those with incomes of $75,000 or more say they had access to temporary or short-term disability insurance and a quarter say they had access to family or medical leave paid by their employer, fewer among those in the middle and lower income groups say the same (19% in each group say they had access to temporary or short-term disability and 15% and 13%, respectively, say they had access to employer-paid family or medical leave).

In addition to cutting back on spending, many cut their leave short, take on debt or use savings to cover lost wages

People who take unpaid or partially paid time off from work for parental, family or medical reasons often have to make financial sacrifices to compensate for the shortfall in earnings. About eight-in-ten (78%) say they cut back on their spending during this time, while half say they used savings they had set aside for something else to cover lost wages or salary. Fewer than half say they used savings they had set aside for the particular situation that led them to take time off (45%), cut their leave short (41%) or took on debt (37%).

A third of leave takers who received no pay or received only some of their regular pay say they put off paying their bills during their time off, while about a quarter say they borrowed money from family or friends (24%) or received money from family or friends that they weren’t expected to pay back (23%). About one-in-five (17%) say they went on public assistance in order to cover lost wages or salary.

A third of leave takers who received no pay or received only some of their regular pay say they put off paying their bills during their time off, while about a quarter say they borrowed money from family or friends (24%) or received money from family or friends that they weren’t expected to pay back (23%). About one-in-five (17%) say they went on public assistance in order to cover lost wages or salary.

While majorities of leave takers across income groups who received no pay or only some pay during their time off say they cut back on spending during this time, those with household incomes under $30,000 are far more likely than those with higher incomes to say they had to take more consequential measures, such as taking on debt, putting off paying their bills, and going on public assistance, in order to cover their lost wages or salary, and this is particularly the case among those who have taken parental leave in the past two years.

About six-in-ten parental-leave takers (57%) with household incomes under $30,000 who did not receive their full pay when they took time off from work following the birth or adoption of their child say they took on debt to deal with the loss of wages or salary; roughly half say they went on public assistance (48%) or put off paying their bills (46%).

Among those with household incomes between $30,000 and $74,999, a smaller but not insignificant share (28%) say they went on public assistance during the time they took off from work following the birth or adoption of their child; just 5% of those with household incomes of $75,000 or more say they did this. About a third (35%) of those in the middle income group also say they put off paying their bills, compared with 13% of those with higher incomes.

Leave takers who received full pay for parental, family or medical time off are more likely to say they then went back to work for same employer

More than eight-in-ten Americans (86%) who took time off from work in the past two years for parental, family or medical reasons say they continued working for the same employer following this time off; 7% went to work for a new employer and 7% did not go back to work.

More than eight-in-ten Americans (86%) who took time off from work in the past two years for parental, family or medical reasons say they continued working for the same employer following this time off; 7% went to work for a new employer and 7% did not go back to work.

Leave takers who received pay – particularly those who were paid the same amount as their regular pay – are more likely than those who took unpaid time off to say they went back to work for the same employer: 97% of those who received full pay and 85% of those who received part of their regular pay say this is the case, compared with 74% of those who did not receive any pay. Among those who did not receive pay, 13% say they went back to work for a new employer and 13% did not go back to work.

One-in-eight mothers (12%) who took time off from work following the birth or adoption of their child say they did not go back to work after their time off; just 1% of fathers say this is the case. Among fathers, 95% went back to work for the same employer; 79% of mothers did the same.

Leave takers with higher incomes and a bachelor’s degree are more likely to say their supervisor was very supportive when they needed to take time off from work

About eight-in-ten leave takers (83%) say their supervisor was at least somewhat supportive when they took time off from work for parental, family or medical reasons, including 56% who say their supervisor was very supportive. Similar shares of those who took time off following the birth or adoption of their child (58%), to care for a family member with a serious health condition (53%) or to deal with their own serious condition (56%) say their supervisor was very supportive when they needed to take time off from work.

About eight-in-ten leave takers (83%) say their supervisor was at least somewhat supportive when they took time off from work for parental, family or medical reasons, including 56% who say their supervisor was very supportive. Similar shares of those who took time off following the birth or adoption of their child (58%), to care for a family member with a serious health condition (53%) or to deal with their own serious condition (56%) say their supervisor was very supportive when they needed to take time off from work.

Older adults, as well as those with higher household incomes, are particularly likely to say their supervisor was very supportive. For example, about two-thirds (66%) of leave takers ages 65 and older and 61% of those ages 50 to 64 say their supervisor was very supportive, compared with 55% of those ages 30 to 49 and 46% of those younger than 30.

Among leave takers with annual household incomes of $75,000 or more, about six-in-ten (61%) say their supervisor was very supportive when they took time off from work, compared with 55% of those with middle incomes and just 38% of those with incomes under $30,000. Similarly, higher shares of those with at least a bachelor’s degree (62%) than those with some college (54%) or with a high school diploma or less (51%) describe their supervisor as very supportive.

When it comes to taking leave following the birth or adoption of a child, mothers and fathers are about equally likely to say their supervisor was very supportive (57% and 59%, respectively). There are also no significant differences in the shares of women and men saying their supervisor was very supportive when they took time off to care for a family member with a serious health condition or to deal with their own serious condition.

The vast majority (89%) of leave takers also say their co-workers were very or somewhat supportive when they took time off from work, with 61% saying their co-workers were very supportive. As is the case with assessments of a supervisor’s support, older leave takers and those with higher incomes are more likely than those who are younger and have lower incomes to say their co-workers were very supportive. Men and women across the different types of leave – parental, family and medical – are about equally likely to report that their co-workers were very supportive when they took time off from work.

Many workers report responding to phone calls, emails while on family or medical leave

Many workers report responding to phone calls, emails while on family or medical leave

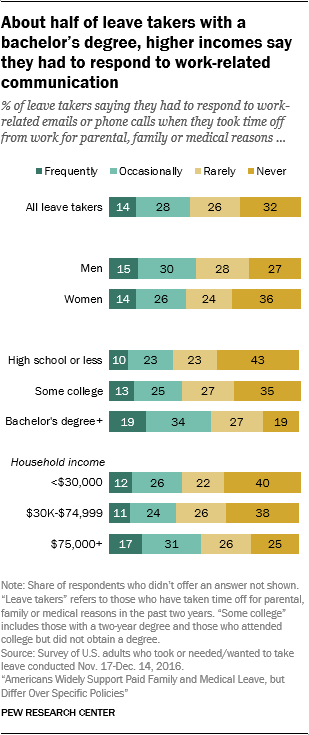

About four-in-ten (42%) leave takers say they had to respond to work-related emails or phone calls during their time off frequently (14%) or occasionally (28%); most say they rarely (26%) or never (32%) had to do this. Those who took time off to care for a family member are more likely than those who took parental or medical leave to say they had to do this at least occasionally (52% vs. 39% each among those who took parental or medical leave).

Leave takers with a bachelor’s degree or more education and those with higher incomes are more likely than those with less education and lower incomes to say they had to respond to work-related emails or phone calls at least occasionally. For example, 53% of those with at least a bachelor’s degree say they had to do this, compared with 38% of those with some college experience and 33% of those with a high school education or less.

Men and women who took leave to care for a family member with a serious health condition or to deal with their own serious condition are about equally likely to say they had to respond to work-related emails or phone calls while they were taking time off from work. Among those who took time off following the birth or adoption of their child, however, a higher share of men than women say they had to do this at least occasionally during their time off (44% vs. 34%).

Most leave takers (69%) who had to respond to work-related email or phone calls at least occasionally say they were not bothered by this, but about three-in-ten (31%) say it did bother them. Those who were taking time off from work following the birth or adoption of their child (38%) or to deal with their own serious health condition (31%) are more likely than those who were taking time off to care for an ill family member (24%) to say it bothered them to have to respond to work-related emails or phone calls.

Many who took or needed or wanted to take time off say it was hard for them to learn about available benefits

Three-in-ten leave takers say it was difficult for them to learn about what leave benefits, if any, were available to them when they took time off from work for parental, family or medical reasons, and this is particularly the case among those who say their supervisor wasn’t supportive when they took time off: 64% of those who say their supervisor was not too or not at all supportive say it was difficult to learn about leave benefits, compared with 24% of those with more supportive supervisors.

Leave takers with lower incomes and without college experience are more likely than those with higher incomes and at least some college experience to say it was difficult for them to learn about leave benefits that might be available to them. For example, about four-in-ten (44%) of those with household incomes under $30,000 said this was the case, compared with 34% of those with incomes between $30,000 and $74,999 and 24% of those with household incomes of $75,000 or more.

Leave takers with lower incomes and without college experience are more likely than those with higher incomes and at least some college experience to say it was difficult for them to learn about leave benefits that might be available to them. For example, about four-in-ten (44%) of those with household incomes under $30,000 said this was the case, compared with 34% of those with incomes between $30,000 and $74,999 and 24% of those with household incomes of $75,000 or more.

Among Hispanics who have taken time off from work for parental, family or medical reasons in the past two years, 43% say it was hard to learn about benefits that might be available, more than the shares of white (27%) or black (30%) leave takers who say the same. Hispanics who needed or wanted to take leave but were not able to do so are also more likely than their white and black counterparts to say it was difficult for them to learn about what benefits, if any, might be available to them when they needed or wanted to take time off (58% vs. 47% and 38%, respectively).

Overall, about half (49%) of those who didn’t take time off when they needed or wanted to say it was hard for them to learn what leave benefits, if any, were available to them when they needed or wanted to take time off from work for parental, family or medical reasons but were not able to do so.

A quarter of women say taking time off from work after birth or adoption had a negative impact on their job or career

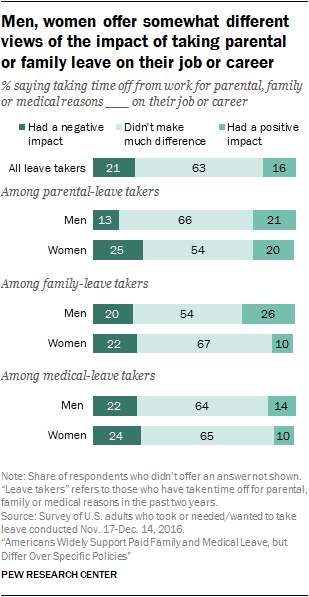

About one-in-five Americans who took leave from work in the past two years (21%) say taking time off had a negative impact on their job or career, while 16% say it had a positive impact; 63% of leave takers say it didn’t make much difference.

About one-in-five Americans who took leave from work in the past two years (21%) say taking time off had a negative impact on their job or career, while 16% say it had a positive impact; 63% of leave takers say it didn’t make much difference.

Among those who took time off from work following the birth or adoption of their child, women are nearly twice as likely as men to say this had a negative impact on their job or career: 25% of women say this, compared with 13% of men. Men, in turn, are more likely than women to say the time they took off following the birth or adoption of their child didn’t make much difference on their job or career (66% vs. 54%).

When it comes to taking time off to care for a family member with a serious health condition, about one-in-five men (20%) and women (22%) say taking time off had a negative impact on their job or career. However, higher shares of men than women who took time off from work for this reason say taking time off had a positive impact at work: About a quarter (26%) of men say this, compared with just 10% of women. There are no gender differences when it comes to assessments of the impact of taking time off to deal with one’s own medical issue.

Assessments of the impact on one’s family of taking leave are decidedly positive, particularly when it comes to taking time off from work following the birth or adoption of a child or to care for a family member with a serious health condition. About eight-in-ten (79%) of those who took parental leave say taking time off had a positive impact on their family, as do 72% of those who were caring for an ill family member. Among those who took time off to deal with their own serious health condition, just 34% say this had a positive impact on their family, while 17% say it had a negative impact and 48% say it didn’t make much difference.

For those who were not able to take time off from work when they needed or wanted to, significant shares say the inability to take leave had a negative impact on their family; overall, 45% say this is the case, while 21% say not taking time off had a positive impact on their family and a third say it didn’t make much difference.

In deciding who will care for an ill family member, geography and closeness of the relationship come into play

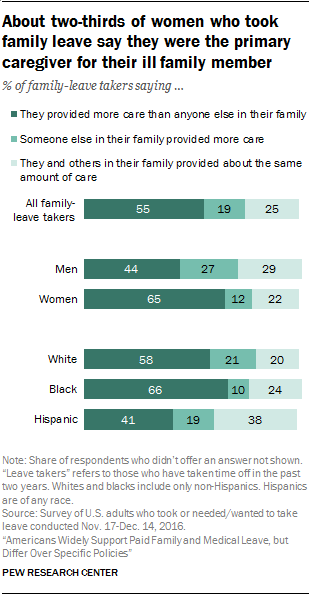

Just over half (55%) of those who took time off from work to care for a family member with a serious health condition in the past two years say that they provided more care than anyone else in their family for these family members; about one-in-five (19%) say someone else in their family provided more care and a quarter say they and others in their family provided about the same amount of care.

Just over half (55%) of those who took time off from work to care for a family member with a serious health condition in the past two years say that they provided more care than anyone else in their family for these family members; about one-in-five (19%) say someone else in their family provided more care and a quarter say they and others in their family provided about the same amount of care.

Primary caregiving responsibilities tend to fall to women more than men. For example, 65% of women who took time off from work to care for an ill family member say they were the primary caregiver, compared with 44% of men. Higher shares of whites and blacks (58% and 66%, respectively) than Hispanics (41%) who took time off from work for this reason say they were the primary caregiver. Hispanics, in turn, are more likely than whites and blacks to say caring responsibilities were shared about equally by them and others in their family (38% vs. 20% and 24%).

Families weigh a variety of factors in deciding how to delegate caregiving responsibilities. Among those who took time off to care for a family member who was ill, about half say they considered who lived closer to the family member who needed care (49%), who had a closer relationship with the family member who needed care (49%), and who would do a better job providing care (48%).8 Some 36% say who had fewer work responsibilities was a factor, while fewer (28%) say who had fewer family responsibilities was a factor.

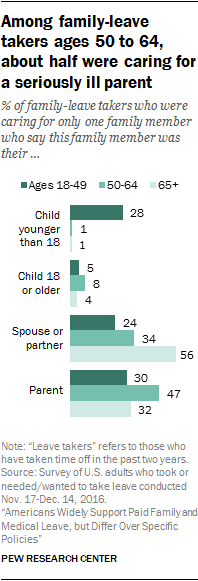

Many ages 65 and older who take time off to care for an ill family member are caring for a spouse or partner; those 50 to 64 tend to be caring for a parent

For the most part, those who took time off from work in the past two years to care for a family member with a serious health condition say they were caring for only one seriously ill family member during this time; 87% say this is the case, while 12% were caring for more than one family member with a serious health condition.

For the most part, those who took time off from work in the past two years to care for a family member with a serious health condition say they were caring for only one seriously ill family member during this time; 87% say this is the case, while 12% were caring for more than one family member with a serious health condition.

Those who were caring for only one family member with a serious health condition were typically caring for one of their parents (36%) or for their spouse or partner (29%). Some 17% say they were caring for their child younger than 18, while fewer say they were caring for their adult child (6%), a sibling (3%) or a grandparent (3%). Adults ages 65 and older who took time off from work to care for a family member with a serious health condition are far more likely than those who are younger to say they were caring for a spouse or partner; 56% in the older group say this, compared with 34% of those 50 to 64 and 24% of those younger than 50. In turn, larger shares of family-leave takers ages 50 to 64 than of those who are younger or older say they were caring for one of their parents when they took time off from work (47% say this vs. 32% of those 65 and older and 30% of those younger than 50). About three-in-ten (28%) adults younger than 50 who took time off from work to care for a family member with a serious health condition say they were caring for their child younger than 18; only 1% of those 50 and older say this.

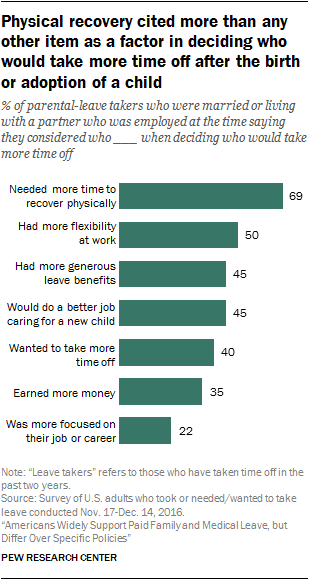

Along with physical recovery, flexibility and generosity of leave are among top factors couples consider when deciding who takes more time off after birth or adoption

Among parental-leave takers with a spouse or partner who was employed at the time, about eight-in-ten (83%) say their spouse or partner took at least some time off from work, even if just a few days, following the birth or adoption of their child, while 17% say their spouse or partner did not take any time off. About a quarter (24%) of women who were married to or living with a partner who was employed when they took leave say their spouse or partner didn’t take any time off after the birth or adoption of their child; just 8% of men say the same about their spouse or partner.

Among parental-leave takers with a spouse or partner who was employed at the time, about eight-in-ten (83%) say their spouse or partner took at least some time off from work, even if just a few days, following the birth or adoption of their child, while 17% say their spouse or partner did not take any time off. About a quarter (24%) of women who were married to or living with a partner who was employed when they took leave say their spouse or partner didn’t take any time off after the birth or adoption of their child; just 8% of men say the same about their spouse or partner.

Nearly all women (95%) who were married or living with a partner who took time off from work following the birth or adoption of their child say their spouse or partner took less time off from work than they did; this is the case whether women were working full time or part time. Among men who took time off from work following the birth or adoption of their child, 82% say their spouse or partner took more time off from work than they did.

When parental-leave takers whose spouse or partner didn’t take time off or who say that one took more time off than the other (rather than saying both took about the same amount of time off) are asked how they decided who would take more time off, most (69%) say they took into account who needed more time to recover physically. About half say they took into consideration who had more flexibility at work (50%), who had more generous leave benefits (45%) and who would do a better job caring for a new child (45%). About four-in-ten say who wanted to take more time off (40%) or who earned more money (35%) was a deciding factor, while 22% say focus on job or career was.

Women and men are generally about equally likely to say each of these was a factor in deciding whether they or their spouse or partner would take more time off from work following the birth or adoption of their child, with two exceptions: Men are more likely than women to say that who wanted to take more time off was a deciding factor (48% vs. 34%), and women are more likely than men to point to earnings as a factor (42% vs. 27%).

Shareable facts on paid family and medical leave

Shareable facts on paid family and medical leave