Police work has always been hard. Today police say it is even harder. In a new Pew Research Center national survey conducted by the National Police Research Platform, majorities of police officers say that recent high-profile fatal encounters between black citizens and police officers have made their jobs riskier, aggravated tensions between police and blacks, and left many officers reluctant to fully carry out some of their duties.

The wide-ranging survey, one of the largest ever conducted with a nationally representative sample of police, draws on the attitudes and experiences of nearly 8,000 policemen and women from departments with at least 100 officers.1 It comes at a crisis point in America’s relationship with the men and women who enforce its laws, precipitated by a series of deaths of black Americans during encounters with the police that have energized a vigorous national debate over police conduct and methods.

Within America’s police and sheriff’s departments, the survey finds that the ramifications of these deadly encounters have been less visible than the public protests, but no less profound. Three-quarters say the incidents have increased tensions between police and blacks in their communities. About as many (72%) say officers in their department are now less willing to stop and question suspicious persons. Overall, more than eight-in-ten (86%) say police work is harder today as a result of these high-profile incidents.

At the same time that black Americans are dying in encounters with police, the number of fatal attacks on officers has grown in recent years. About nine-in-ten officers (93%) say their colleagues worry more about their personal safety – a level of concern recorded even before a total of eight officers died in separate ambush-style attacks in Dallas and Baton Rouge last July.

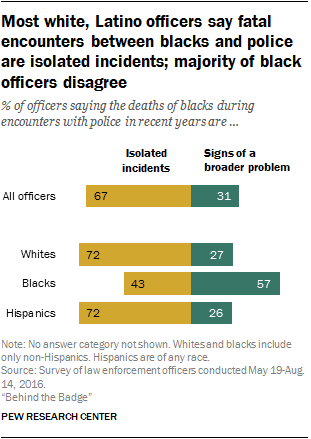

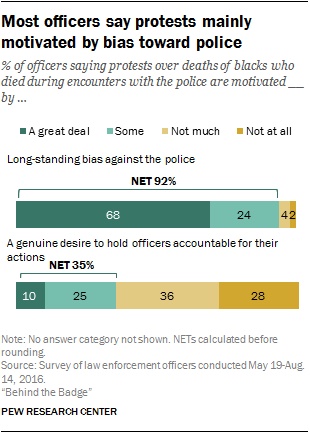

The survey also finds that officers remain deeply skeptical of the protests that have followed deadly encounters between police and black citizens. Two-thirds of officers (68%) say the demonstrations are motivated to a great extent by anti-police bias; only 10% in a separate question say protesters are similarly motivated by a genuine desire to hold police accountable for their actions. Some two-thirds characterize the fatal encounters that prompted the demonstrations as isolated incidents and not signs of broader problems between police and the black community – a view that stands in sharp contrast with the assessment of the general public. In a separate Pew Research Center survey of U.S. adults, 60% say these incidents are symptoms of a deeper problem.

A look inside the nation’s police departments reveals that most officers are satisfied with their department as a place to work and remain strongly committed to making their agency successful. Still, about half (53%) question whether their department’s disciplinary procedures are fair, and seven-in-ten (72%) say that poorly performing officers are not held accountable.

Conflicting experiences and emotions mark police culture

Other survey findings underscore the duality of police work and the emotional toll that police work can take on officers. About eight-in-ten (79%) say they have been thanked by someone for their service in the month prior to the survey while on duty. But also during that time two-thirds say they have been verbally abused by a member of their community, and a third have fought or physically struggled with a suspect. A majority of officers (58%) say their work nearly always or often makes them feel proud. But nearly the same share (51%) say the job often frustrates them. More than half (56%) say their job has made them more callous.

Most police officers feel respected by the public and, in turn, believe officers have little reason to distrust most people. Rather than viewing the neighborhoods where they work as hostile territory, seven-in-ten officers say that some or most of the residents of the areas they patrol share their values. At the same time, a narrow majority of officers (56%) believe an aggressive rather than courteous approach is more effective in certain neighborhoods, and 44% agree that some people can only be brought to reason the hard, physical way.

Long-standing tensions between police and blacks underlie many of the survey results. While substantial majorities of officers say police have a good relationship with whites, Hispanics and Asians in their communities, 56% say the same about police relations with blacks. This perception varies dramatically by the race or ethnicity of the officer. Six-in-ten white and Hispanic officers characterize police relations with blacks as excellent or good, a view shared by only 32% of their black colleagues.

The racial divide looms equally large on other survey questions, particularly those that touch on race. When considered together, the frequency and sheer size of the differences between the views of black and white officers mark one of the singular findings of this survey. For example, only about a quarter of all white officers (27%) but seven-in-ten of their black colleagues (69%) say the protests that followed fatal encounters between police and black citizens have been motivated at least to some extent by a genuine desire to hold police accountable.

And when the topic turns more broadly to the state of race relations, virtually all white officers (92%) but only 29% of their black colleagues say that the country has made the changes needed to assure equal rights for blacks. Not only do the views of white officers differ from those of their black colleagues, but they stand far apart from those of whites overall: 57% of all white adults say no more changes are needed, as measured in the Center’s survey of the general public.

Public, police differ on some key issues

Further differences in attitudes and perceptions emerge when the views of officers are compared with those of the public on other questions. While two-thirds of all police officers say the deaths of blacks at the hands of police are isolated incidents, only about four-in-ten members of the public (39%) share this view while the majority (60%) believes these encounters point to a broader problem between police and blacks.

And while a majority of Americans (64%) favor a ban on assault-style weapons, a similar share of police officers (67%) say they would oppose such a ban.

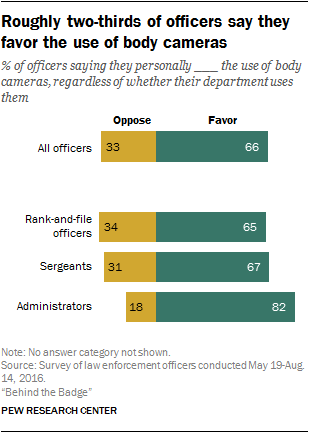

On other issues the public and police broadly agree. Majorities of both groups favor the use of body cameras by officers to record interactions with citizens (66% of officers and 93% of the public). And about two-thirds of police (68%) and a larger share of the public (84%) believe the country’s marijuana laws should be relaxed, and a larger share of the public than the police support legalizing marijuana for both private and medical use (49% vs. 32%).

These findings come from two separate Pew Research Center surveys. The main survey is an online poll of a nationally representative sample of 7,917 officers working in 54 police and sheriff’s departments with 100 or more sworn officers. (Some 63% of all sworn officers work in departments of this size.) The National Police Research Platform, headquartered at the University of Illinois at Chicago during the study period, conducted this survey of police for the Pew Research Center May 19-Aug. 14, 2016, using its panel of police agencies. The NPRP panel is described in more detail in the methodology.

The views of the public included in this report drew from a Pew Research Center American Trends Panel survey of 4,538 U.S. adults conducted online and by mail Aug. 16-Sept. 12, 2016. That survey included many of the same questions asked on the police survey, allowing direct comparisons to be made between the views of officers and the public.

Contrasting experiences, conflicting emotions

The survey provides a unique window into how police officers see their role in the community, how they assess the dangers of the job and what they encounter on a day-to-day basis. It also gives a glimpse into the psychology of policing and the way in which officers approach the moral and ethical challenges of the job.

Police have a nuanced view of their role – they don’t see themselves as just protectors or as enforcers. A majority (62%) say they fill both of these roles equally. They also experience a range of emotions on the job – often conflicting ones. A majority of officers (58%) say their work nearly always or often makes them feel proud. Almost as many (51%) say they nearly always or often feel frustrated by the job.

Officers are somewhat less likely to say they feel fulfilled by their job (42% say nearly always or often). Relatively few officers (22%) say their job often makes them feel angry, but a significant share (49%) say it sometimes makes them feel this way. Officers who say their job often makes them feel angry seem to be less connected to the citizens they serve. Fully 45% say very few or none of the people in the neighborhoods they serve share their values. Only 20% of officers who say they hardly ever or never feel angry say the same.

White officers are significantly more likely than black officers to associate negative emotions with their job. For example, 54% of white officers say they nearly always or often feel frustrated by their work, while roughly four-in-ten (41%) black officers say the same. Hispanic officers fall in the middle on this measure.2

Officers worry about their safety and think the public doesn’t understand the risks they face

Fatal encounters between blacks and police have dominated the headlines in recent years. But the story took on another twist with the ambush-style attack that killed five police officers last summer in Dallas. Because these attacks occurred while the survey was in the field, it was possible to see if safety concerns of officers were affected by the incidents by comparing views before and after the assault.

Overall, the vast majority of officers say they have serious concerns about their physical safety at least sometimes when they are on the job. Some 42% say they nearly always or often have serious concerns about their safety, and another 42% say they sometimes have these concerns. The share of police saying they often or always have serious concerns about their own safety remained fairly consistent in interviews conducted pre-Dallas to post-Dallas.3

While physical confrontations are not a day-to-day occurrence for most police officers, they are not altogether infrequent. A third of all officers say that in the past month, they have physically struggled or fought with a suspect who was resisting arrest. Male officers are more likely than their female counterparts to report having had this type of encounter in the past month – 35% of men vs. 22% of women. And white officers (36%) are more likely than black officers (20%) to say they have struggled or fought with a suspect in the past month. Among Hispanic officers, 33% say they had an encounter like this.

Although police officers clearly recognize the dangers inherent in their job, most believe the public doesn’t understand the risks and challenges they face. Only 14% say the public understands these risks very or somewhat well, while 86% say the public doesn’t understand them too well or at all.4 For their part, the large majority of American adults (83%) say they do understand the risks law enforcement officers face.

Police interactions with the public can range from casual encounters to moments of high stress. And the reactions police report getting from community members reflect the diverse nature of those contacts. Large majorities of officers across most major demographic groups report that they have been thanked for their service, but there are significant differences across key demographic groups when it comes to verbal abuse. Men are more likely than women to say they have been verbally abused by a community member in the past month. White and Hispanic officers are more likely than black officers to have had this experience. And a much higher share of younger officers (ages 18 to 44) report being verbally abused – 75%, compared with 58% of their older counterparts.

The situations police face on the job can often present moral dilemmas. When asked how they would advise a fellow officer in an instance where doing what is morally the right thing would require breaking a department rule, a majority of police (57%) say they would advise their colleague to do the morally right thing. Four-in-ten say they would advise the colleague to follow the department rule. There’s a significant racial divide on this question: 63% of white officers say they would advise doing the morally right thing, even if it meant breaking a department rule; only 43% of black officers say they would give the same advice.

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, there were 15,388 state and local law enforcement agencies, employing more than 750,000 sworn officers in 2013 (the most recently available data). The majority of these agencies were local municipal police departments (12,326). There were 3,012 sheriff’s departments, which serve areas of the country that do not lie within the jurisdictions of police departments of incorporated municipalities, though some small cities contract with the local sheriff’s department for police services. There are also 50 primary state police agencies.

The Pew Research Center survey conducted by the National Police Research Platform is representative of officers nationwide in local police and sheriff’s departments with at least 100 full-time police officers. A majority of full-time sworn officers (477,317) were part of local police departments in 2013. Agencies with at least 100 full-time equivalent officers employed 63% of the nation’s full-time officers even though these departments accounted for only 5% of all local police departments (or 645 departments). It is these larger local police agencies that have been at the center of recent national conversations on policing.

In 2013, more than a quarter (27%) of full-time police officers were racial or ethnic minorities. Some 12% of full-time local police officers were black; another 12% were Hispanic; and 4% were Asian, Pacific Islander, American Indian or multiracial. By comparison, 12% of the U.S. adult population was black; 15% was Hispanic; and 8% was some other racial or ethnic minority in 2013. Women remain underrepresented in the field, making up just 12% of full-time officers in 2013; women are 51% of the U.S. adult population.

In general, departments that serve larger populations are more racially and ethnically diverse and tend to have a higher share of women serving as full-time officers. For example, more than four-in-ten officers serving populations of 500,000 or more were racial or ethnic minorities in 2013, compared with fewer than one-in-five in jurisdictions with less than 50,000 people.

Police are highly committed to their work but say more officers are needed

A look inside the nation’s police departments reveals a great deal about how officers view their jobs, their leadership and their resources. For the most part police officers give their workplace a positive rating and are committed to their agency’s success. A solid majority of officers are either very satisfied (16%) or satisfied (58%) with their agency as a place to work. And an overwhelming share of officers (96%) agree that they are strongly committed to making their agency successful.

Still, police do not offer universal praise of their departmental leadership. Only three-in-ten say they are extremely (7%) or very (23%) supportive of the direction that top management is taking their organization. About half are moderately (28%) or slightly (19%) supportive and 15% are not supportive at all.

And police express serious concerns about resource limitations. At the most basic level, most police (86%) say their department does not have enough officers to adequately police the community. Police who work in larger agencies (with 1,000 officers of more) are more likely than those working in smaller agencies to say that there is a shortage of officers in their department (95% vs. 79%).

Police give their departments relatively positive, though not exemplary, ratings for training and equipping officers to do their jobs. Roughly four-in-ten officers (39%) say their department has done very well in terms of training them adequately for their job, and a similar share (37%) give their department high marks for clearly communicating the responsibilities of the job. About three-in-ten officers (31%) say their department has done very well when it comes to equipping them to perform their job. On each of these dimensions, about four-in-ten officers say their department has done somewhat well, while about one-in-five rate their department’s performance as not too well or not at all well in these areas.

Again there are gaps by department size, with smaller departments (1,000 officers or fewer) giving their leadership significantly higher ratings when it comes to training and equipping them, as well as communicating job expectations.

Most officers say their use-of-force guidelines are appropriate and helpful

As many departments grapple with use-of-force policies and training, most officers say their own agency’s guidelines strike the right balance. About one-in-four (26%) say the rules governing use of force in their department are too restrictive, while 73% say they are about right (1% say the guidelines are not restrictive enough).

Roughly a third (34%) of officers say their department’s guidelines are very useful when police are confronted with actual situations where force may be necessary. An additional 51% say the guidelines are somewhat useful. Some 14% say they are not too useful or not at all useful. And when the department guidelines are not being followed, police overwhelmingly say fellow officers need to step up. Fully 84% say officers should be required to intervene when they believe another officer is about to use unnecessary force; just 15% say they should not be required to intervene.

In terms of striking the right balance between acting decisively versus taking time to assess a situation, police tend to be more concerned that officers in their department will spend too much time diagnosing a situation before acting (56% worry more about this) than they are about officers not spending enough time before acting decisively (41%).

Black officers are much more likely than white or Hispanic officers to say they worry more that officers will not spend enough time diagnosing a situation before acting (61% for blacks vs. 37% for whites and 44% of Hispanics). Overall, blacks and department administrators (59%) are the only two major groups in which a majority is more concerned that officers will act too quickly than worry that they will wait too long before responding to a situation.

Officers give their departments mixed ratings for their disciplinary processes. About half (45%) agree that the disciplinary process in their agency is fair, while 53% disagree (including one-in-five who strongly disagree). When they are asked more specifically about the extent to which underperforming officers are held accountable, police give more negative assessments of their departments. Only 27% agree that officers who consistently do a poor job are held accountable, while 72% disagree with this.

Most officers have had at least some training in key areas of reform

Reforming law enforcement tactics and procedures – particularly as they relate to the use of force – has become an important focus both inside and outside the police department. In the wake of recent fatalities of blacks during encounters with police, recommendations have been made to prevent these types of situations from occurring.

The survey finds broad support among police, especially administrators, for the use of body cameras. Even so, officers are somewhat skeptical that their use would change police behavior. Half of all officers say body cameras would make police more likely to act appropriately, while 44% say this wouldn’t make any difference.

Despite the national attention given to training and reforms aimed at preventing the use of unnecessary force, relatively few (half or fewer rank-and-file officers) report having had at least four hours of training in some specific areas over the preceding 12 months.

About half of rank-and-file officers say they have had at least four hours of firearms training in the last 12 months involving shoot-don’t shoot scenarios (53%) and nonlethal methods to control a combative or threatening individual (50%). Some 46% of officers have had at least four hours of training in how to deal with individuals who are having a mental health crisis, and 44% say they have had at least four hours of training in how to de-escalate a situation so it is not necessary to use force.

About four-in-ten officers say they have received at least four hours of training in bias and fairness (39%) and how to deal with people so they feel they’ve been treated fairly and respectfully (37%).

Most officers say high-profile incidents have made policing harder

Whether an officer works in a department that employs hundreds or thousands of sworn officers or is located in a quiet suburb or bustling metropolis, police say their jobs are harder now as a consequence of recent high-profile fatal incidents involving blacks and police.

Overall, fully 86% of officers say their jobs are harder, including substantial majorities of officers in police departments with fewer than 300 officers as well as those working in “mega departments” with 2,600 officers or more (84% and 89%, respectively). In fact, across every major demographic group analyzed for this survey, about eight-in-ten officers or more say these high-profile incidents have made policing more challenging and more dangerous.

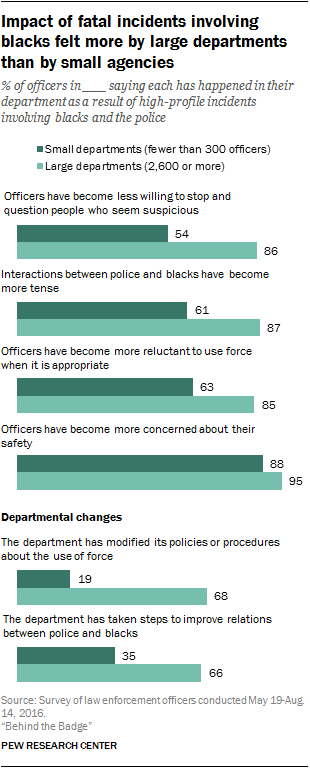

While the impact of these incidents is broadly felt, officers in larger departments are far more likely than those in small agencies to say these incidents have had an impact. For example, roughly half of officers (54%) in departments with fewer than 300 officers say their peers have become less willing to stop and question people who seem suspicious. By contrast, fully 86% of police in departments with 2,600 officers or more say fellow officers are now more hesitant to question people who look or act suspicious. Similarly, roughly nine-in-ten officers (87%) in the largest departments say that police interactions with blacks have become more tense; 61% of officers in small departments agree.

Police in larger departments also are more likely than those in small agencies to say officers in their department are more reluctant to use force to control a suspect even when it is appropriate, a move that police critics may view as a positive sign but others may see as putting officers at increased risk.

The survey also found that roughly half (46%) of officers say fatal encounters between blacks and police in recent years have prompted their department to modify their use-of-force policies. Officers in large departments are more than three times as likely to report that their departments have made this change as small agencies (68% vs. 19%). About two-thirds of police in larger departments (66%) say their departments have taken steps to improve relations with black residents. By contrast, about a third of officers in small departments (35%) have made similar outreach efforts.

How officers view police relations with whites and minorities

Large majorities of white, black and Hispanic officers agree that police and whites in their communities get along.5 But striking differences emerge when the focus shifts to police relations with racial and ethnic minorities. A consistently smaller share of black officers than their white or Hispanic colleagues say the police have a positive relationship with minorities in the community they serve. Roughly a third of all black officers (32%) characterize relations with blacks in their community as either excellent or good, while majorities of white and Hispanic officers (60% for both) offer a positive assessment.

At the same time, only about half of all black officers (46%) but large majorities of Hispanic (71%) and white (76%) officers say relations between police and Hispanics are excellent or good. Similarly, three-quarters of all black officers but 91% of white officers and 88% of Hispanic officers rate relations with Asians in their communities positively.

Majority of police view fatal encounters as isolated incidents

Two-thirds of police officers (67%) say the highly publicized fatal encounters between police and blacks are isolated incidents, while 31% describe them as signs of a broader problem. Yet underlying this result are striking differences between the views of black and white officers – differences that mirror the broader fault lines in society at large on racial issues.

A majority of black officers (57%) say these encounters are evidence of a broader problem between police and blacks, a view held by only about a quarter of all white (27%) and Hispanic (26%) officers.

Black female officers in particular are more likely to say these incidents signal a more far-reaching concern. Among all sworn officers, 63% of black women say this, compared with 54% of black men.

Widespread doubts about protesters’ motives

Most police officers are deeply skeptical of the motives of the demonstrators who protested after many of the deadly encounters between police and blacks. Fully nine-in-ten (92%) believe that long-standing bias against the police is a great deal (68%) or some (24%) of the motivation behind these demonstrations. In sharp contrast, only about a third (35%) of officers say in a separate question that a genuine desire to hold officers accountable for their actions is at least some of the motivation for the protests.

Once again, race pushes police in opposite directions. Among black officers, 69% say the protests were sincere efforts to force police accountability – more than double the proportion of whites (27%) who share this view. Female officers, older police and department administrators also are more likely than male officers, younger police and rank-and-file officers to believe protesters genuinely seek police accountability.

Support for aggressive, physical tactics

The law gives police great discretion in how they interact with citizens. Depending on the situation, these techniques can range from polite persuasion to the use of forceful and more pointed verbal commands to the extreme physical measures that officers sometimes use, often as a last resort, to control threatening or combative individuals. The use of these more severe techniques has been a main focus of the national debate over police methods.

To measure their attitudes toward more aggressive tactics, officers were asked how much they agreed or disagreed with two statements. The first statement read, “In certain areas of the city it is more useful for an officer to be aggressive than to be courteous.” The second measured support for the assertion that “some people can only be brought to reason the hard, physical way.”

A narrow majority of officers (56%) feel that in some neighborhoods being aggressive is more effective than being courteous, while 44% agree or strongly agree that hard, physical tactics are necessary to deal with some people.

On both measures, a larger share of younger, less senior officers and those with less than five years of experience favor these techniques, while proportionally fewer older, more experienced officers or department administrators endorse them.

A majority of officers say they have become more callous

There’s a saying in police work that officers see things the public doesn’t see – and also things the public shouldn’t see. Exposure to the dark side of life, coupled with the stress that officers encounter working in high-pressure situations or with hostile individuals, means that many officers may pay an emotional price for their service.

For example, a 56% majority of officers say they have become more callous toward people since taking their job. Younger officers and white officers are more likely than older or black officers to say they have become more callous.

Officers who report they have grown more callous are also more likely than their colleagues to endorse aggressive or physically harsh tactics with some people or in some parts of the community. They also are more likely than other officers to say they are frequently angered or frustrated by their jobs or to have been involved in a physical or verbal confrontation with a citizen in the past month or to have fired their service weapon while on duty at some point in their careers.

It is difficult to discern with these data whether increased callousness is a primary cause or a consequence of feelings of anger or frustration, or attitudes toward aggressive tactics. However, the data suggest that these feelings and behaviors are related. For example, officers who sense they have become more callous on the job are about twice as likely as those who say they have not to say their job nearly always or often makes them feel angry (30% vs. 12%). They also are more likely to feel frustrated by their job (63% vs. 37%).

Among those officers who say they have become more callous, about four-in-ten (38%) physically struggled or fought with a suspect in the previous month compared with 26% of those who say they have not become more insensitive.

Similarities and differences between police and public views

On a range of issues and attitudes, police and the public often see the world in very different ways. For example, when both groups are asked whether the public understands the risks and rewards of police work, fully eight-in-ten (83%) of the public say they do, while 86% of police say they don’t – the single largest disparity measured in these surveys.

And while the country is divided virtually down the middle over the need to continue making changes to obtain equal rights for blacks, the overwhelming majority of police (80%) say no further changes are necessary. The public also is twice as likely as police to favor a ban on assault-style weapons (64% vs. 32%).

Yet these differences in views are matched by equally significant areas of broad agreement. Large majorities of officers (92%) and the public (79%) say anti-police bias is at least somewhat of a motivation for those protesting the deaths of blacks at the hands of police. Majorities of police and the public favor the use of body cameras by officers, though a significantly larger share of the public supports their use (93% vs. 66%) and sees more benefits from body cams than the police do.

While they disagree about an assault weapons ban, large majorities of the police (88%) and the public (86%) favor making private gun sales and sales at gun shows subject to background checks. Majorities also favor creating a federal database to track all gun sales (61% for police and 71% of the public).

The remainder of this report explores in greater detail the working lives, experiences and attitudes of America’s police officers. Chapter 1 examines police culture, how officers view their job as well as the risks and rewards of police work. Chapter 2 reports how officers view their departments and their superiors as well as officers’ attitudes toward the internal rules and policies that govern how they do their job, including the use of force. Chapter 3 looks at how officers view the citizens they serve and how they think the citizens view them, including officers’ perceptions of the relations between police and whites, blacks and other minority groups in their communities. Chapter 4 explores police reaction to recent fatal encounters between blacks and police, the protests that followed many of these incidents and the impact those events have had on how officers do their job. Chapter 5 looks at how officers view various police reforms, including the use of body cameras, and reports on the kinds of police training officers receive to help reduce bias, de-escalate threatening situations as well as how to know when – and when not to – use their service weapons or use deadly force. The final chapter compares and contrasts the views of police with those of the public on a wide range of issues relevant to police work, including attitudes toward gun law reforms and changes to the country’s marijuana laws. It also explores how each group views recent fatal encounters between blacks and police as well as the protests that have frequently followed those incidents.

Other key findings:

- About half of black officers (53%) say that whites are treated better than minorities in their department or agency when it comes to assignments and promotions. Few Hispanic (19%) or white officers (1%) agree. About six-in-ten white and Hispanic officers say minorities and whites are treated the same (compared with 39% of black officers).

- Most officers say that outside of required training, they have not discharged their service firearm while on duty; 27% say they have done this. Male officers are about three times as likely as female officers to say they have fired their weapon while on duty – 30% of men vs. 11% of women.

- Roughly three-in-ten officers (31%) say they have patrolled on foot continuously for 30 minutes or more in the past month; 68% say they have not done this.

- Officers are divided over whether local police should take an active role (52%) in identifying undocumented immigrants rather than leaving this task mainly to federal authorities (46%).

- The share of sworn officers who are women or minorities has increased slowly in recent decades. Since 1987 the share of female officers has grown from 8% to 12% in 2013, the last year the federal Department of Justice measured the demographic characteristics of police agencies. During that time, the share of black officers increased from 9% to 12% while the Hispanic share more than doubled, from 5% to 12%.

- About seven-in-ten officers say some or most of the people in the neighborhoods where they routinely work share their values and beliefs. Officers in larger departments are less likely than those in smaller departments to say they share values with the people in the areas where they patrol.

- About half (51%) of police officers compared with 29% of all employed adults say their job nearly always or often frustrates them, while about four-in-ten officers (42%) and half of employed adults (52%) say their work frequently makes them feel fulfilled.

- A large majority of all officers (76%) say that responding effectively to people who are having a mental health crisis is an important role for police. An additional 12% say this is a role for them, though not an important one and 11% say this is not a role for police.

Throughout this report, “department” and “agency” are used interchangeably and refer to both municipal police departments and county sheriff’s departments.

The terms “police officer” and “officer” refer to sworn officers in both police and sheriff’s departments. References to “officers” or “all officers” include rank-and-file officers, sergeants and administrators.

References to rank-and-file officers include sworn personnel assigned to patrol, detectives and non-supervisory personnel assigned to specific units such as narcotics, traffic or community policing. Sergeants are first-line supervisors. Administrators are officers with the rank of lieutenant or higher, including senior command officers.

References to whites and blacks include only those who are non-Hispanic and identify as only one race. Hispanics are of any race.

References to urban and suburban police officers are based on the ZIP code in which their department is located. Urban police officers are defined as those whose department is within the central city of a Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA). Suburban officers are those whose department is within an MSA, but not within a central city.

Video: How police view their jobs

Video: How police view their jobs