Almost eight years after Barack Obama’s election as the nation’s first black president –an event that engendered a sense of optimism among many Americans about the future of race relations1 – a series of flashpoints around the U.S. has exposed deep racial divides and reignited a national conversation about race. A new Pew Research Center survey finds profound differences between black and white adults in their views on racial discrimination, barriers to black progress and the prospects for change. Blacks, far more than whites, say black people are treated unfairly across different realms of life, from dealing with the police to applying for a loan or mortgage. And, for many blacks, racial equality remains an elusive goal.

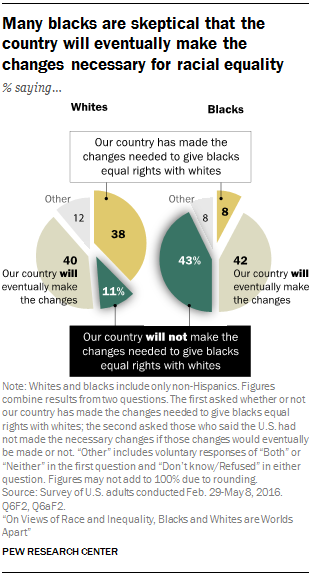

An overwhelming majority of blacks (88%) say the country needs to continue making changes for blacks to have equal rights with whites, but 43% are skeptical that such changes will ever occur. An additional 42% of blacks believe that the country will eventually make the changes needed for blacks to have equal rights with whites, and just 8% say the country has already made the necessary changes.

A much lower share of whites (53%) say the country still has work to do for blacks to achieve equal rights with whites, and only 11% express doubt that these changes will come. Four-in-ten whites believe the country will eventually make the changes needed for blacks to have equal rights, and about the same share (38%) say enough changes have already been made.

These findings are based on a national survey by Pew Research Center conducted Feb. 29-May 8, 2016, among 3,769 adults (including 1,799 whites, 1,004 blacks and 654 Hispanics).2 The survey – and the analysis of the survey findings – is centered primarily around the divide between blacks and whites and on the treatment of black people in the U.S. today. In recent years, this centuries-old divide has garnered renewed attention following the deaths of unarmed black Americans during encounters with the police, as well as a racially motivated shooting that killed nine black parishioners at a church in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2015.

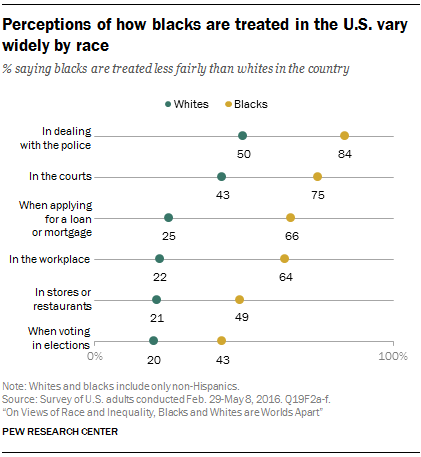

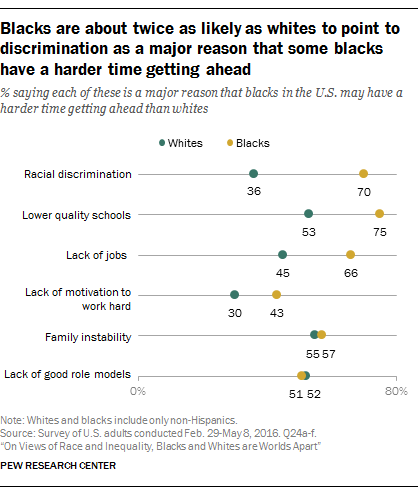

The survey finds that black and white adults have widely different perceptions about what life is like for blacks in the U.S. For example, by large margins, blacks are more likely than whites to say black people are treated less fairly in the workplace (a difference of 42 percentage points), when applying for a loan or mortgage (41 points), in dealing with the police (34 points), in the courts (32 points), in stores or restaurants (28 points), and when voting in elections (23 points). By a margin of at least 20 percentage points, blacks are also more likely than whites to say racial discrimination (70% vs. 36%), lower quality schools (75% vs. 53%) and lack of jobs (66% vs. 45%) are major reasons that blacks may have a harder time getting ahead than whites.

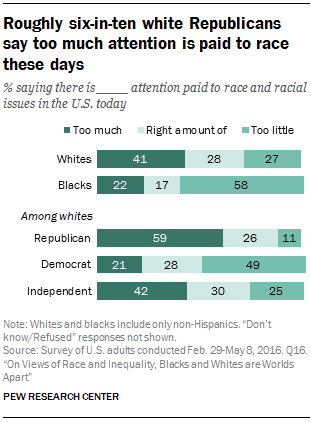

More broadly, blacks and whites offer different perspectives of the current state of race relations in the U.S. White Americans are evenly divided, with 46% saying race relations are generally good and 45% saying they are generally bad. In contrast, by a nearly two-to-one margin, blacks are more likely to say race relations are bad (61%) rather than good (34%). Blacks are also about twice as likely as whites to say too little attention is paid to race and racial issues in the U.S. these days (58% vs. 27%). About four-in-ten whites (41%) – compared with 22% of blacks – say there is too much focus on race and racial issues.

Blacks and whites also differ in their opinions about the best approach for improving race relations: Among whites, more than twice as many say that in order to improve race relations, it’s more important to focus on what different racial and ethnic groups have in common (57%) as say the focus should be on what makes each group unique (26%). Among blacks, similar shares say the focus should be on commonalities (45%) as say it should be on differences (44%).

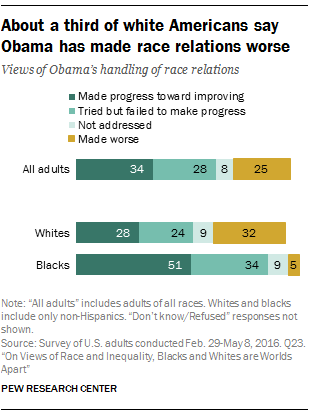

When asked specifically about the impact President Barack Obama has had on race relations in the U.S., a majority of Americans give the president credit for at least trying to make things better, but a quarter say he has made race relations worse. Blacks and whites differ significantly in their assessments. Some 51% of blacks say Obama has made progress toward improving race relations, and an additional 34% say he has tried but failed to make progress. Relatively few blacks (5%) say Obama has made race relations worse, while 9% say he hasn’t addressed the issue at all.

Among whites, 28% say Obama has made progress toward improving race relations and 24% say he has tried but failed to make progress. But a substantial share of whites (32%) say Obama has made race relations worse. This is driven largely by the views of white Republicans, 63% of whom say Obama has made race relations worse (compared with just 5% of white Democrats).

When asked about their views of Black Lives Matter, the activist movement that first came to national prominence following the 2014 shooting death of an unarmed black 18-year-old by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, roughly two-thirds (65%) of blacks express support, including 41% who strongly support it. Among whites, four-in-ten say they support the Black Lives Movement at least somewhat, and this is particularly the case among white Democrats and those younger than 30.

Across the survey’s findings, there are significant fault lines within the white population – perhaps none more consistent than the partisan divide. For example, among whites, Democrats and Republicans differ dramatically on the very salience of race issues in this country. About six-in-ten (59%) white Republicans say too much attention is paid to race and racial issues these days, while only 21% of Democrats agree. For their part, a 49% plurality of white Democrats say too little attention is paid to race these days, compared with only 11% of Republicans.

And while about eight-in-ten (78%) white Democrats say the country needs to continue making changes to achieve racial equality between whites and blacks, just 36% of white Republicans agree; 54% of white Republicans believe the country has already made the changes necessary for blacks to have equal rights with whites.

How blacks and whites view the state of race in America

There are large gaps between blacks and whites in their views of race relations and racial inequality in the United States. Explore how the opinions of blacks and whites vary by age, education, gender and party identification in key questions from our report.

The economic realities of black and white households

Trends in key economic and demographic indicators provide some context for the experiences and outlook of blacks today. While there has been clear progress in closing the white-black gap in some areas – particularly when it comes to high school completion rates – decades-old black-white gaps in economic well-being persist and have even widened in some cases.

According to a new Pew Research Center analysis of data from the U.S. Census Bureau, in 2014 the median adjusted income for households headed by blacks was $43,300, and for whites it was $71,300. 3 Blacks also lag behind whites in college completion, but even among adults with a bachelor’s degree, blacks earned significantly less in 2014 than whites ($82,300 for households headed by a college-educated black compared with $106,600 for comparable white households).

The racial gap extends to household wealth – a measure where the gap has widened since the Great Recession. In 2013, the most recent year available, the median net worth of households headed by whites was roughly 13 times that of black households ($144,200 for whites compared with $11,200 for blacks).

For most Americans, household wealth is closely tied to home equity, and there are sharp and persistent gaps in homeownership between blacks and whites. In 2015, 72% of white household heads owned a home, compared with 43% of black household heads.

And on the flipside of wealth – poverty – racial gaps persist, even though the poverty rate for blacks has come down significantly since the mid-1980s. Blacks are still more than twice as likely as whites to be living in poverty (26% compared with 10% in 2014).

Blacks and whites are divided on reasons that blacks may be struggling to get ahead

Despite these economic realities, when asked about the financial situation of blacks compared with whites today, about four-in-ten blacks either say that both groups are about equally well off (30%) or that blacks are better off than whites financially (8%). Still, about six-in-ten (58%) blacks say that, as a group, they are worse off than whites.

Among whites, a plurality (47%) say blacks are worse off financially, while 37% say blacks are about as well off as whites and 5% say blacks are doing better than whites.

Blacks and whites with a bachelor’s degree are more likely than those with less education to say blacks are worse off financially than whites these days. Roughly eight-in-ten (81%) blacks with a four-year college degree say this, compared with 61% of blacks with only some college education and 46% of blacks with a high school diploma or less. In a similar pattern, about two-thirds (66%) of white college graduates say blacks are worse off financially than whites, while fewer among those who attended college but did not receive a degree (47%) and those who did not attend college (29%) say the same.

When asked about the underlying reasons that blacks may be having a harder time getting ahead than whites, large majorities of black adults point to societal factors. Two-thirds or more blacks say failing schools (75%), racial discrimination (70%) and a lack of jobs (66%) are major reasons that black people may have a harder time getting ahead these days.

On each of these items, the views of blacks differ significantly from those of whites. But, by far, the biggest gap comes on racial discrimination, where only 36% of whites say this is a major reason that blacks may be struggling to get ahead, 34 percentage points lower than the share of blacks who say the same.

The views of blacks and whites are more closely aligned when it comes to the impact that family instability (57% and 55%, respectively) and a lack of good role models (51% and 52%) has on black progress. However, the relative ranking of these items varies among blacks and whites. While whites rank family instability and a lack of good role models above or on a par with societal factors as major reasons that blacks may have a harder time getting ahead than whites, fewer blacks say these items are major reasons than say the same about lower quality schools, discrimination, and lack of jobs.

Blacks are more likely than whites to say a lack of motivation to work hard may be holding blacks back: 43% of black adults and 30% of whites say this is a major reason blacks are having a harder time getting ahead than whites. 4

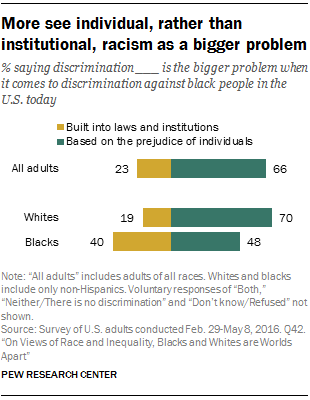

More whites and blacks say individual discrimination is a bigger problem than institutional racism

On balance, the public thinks that when it comes to discrimination against black people in the U.S. today, discrimination that is based on the prejudice of individual people is a bigger problem than discrimination that is built into the nation’s laws and institutions. This is the case among both blacks and whites, but while whites offer this opinion by a large margin (70% to 19%), blacks are more evenly divided (48% to 40%).

Still, large majorities of black adults say that blacks in this country are treated unfairly in a range of institutional settings – from the criminal justice system, to the workplace to banks and financial institutions.

Fully 84% of blacks say that black people in this country are treated less fairly than whites in dealing with the police, and three-quarters say blacks are treated less fairly in the courts.

Roughly two-thirds of black adults say that blacks are treated less fairly than whites when applying for a loan or mortgage (66%) and in the workplace (64%). Somewhat smaller shares – though still upwards of four-in-ten – see unfair treatment for blacks in stores and restaurants (49%) and when voting in elections (43%).

Across all of these realms, whites are much less likely than blacks to perceive unequal treatment – with differences ranging from 23 to 42 percentage points.

Personal experiences with discrimination

A majority of blacks (71%) say that they have experienced discrimination or been treated unfairly because of their race or ethnicity. Roughly one-in-ten (11%) say this happens to them on a regular basis, while 60% say they have experienced this rarely or from time to time.

Among blacks, men and women are equally likely to report having personally experienced racial discrimination, and there are no large gaps by age. There is an educational divide, however: Blacks with at least some college experience (81%) are much more likely than blacks who never attended college (59%) to say they have been discriminated against because of their race.

Experiences with racial discrimination are far less common among whites, but a sizable minority (30%) of white adults report that they have been discriminated against or treated unfairly because of their race or ethnicity. Only 2% say this happens to them regularly and 28% say it occurs less frequently. Whites who say they have a lot of contact with blacks are more likely to say they’ve been discriminated against because of their race than are whites who have less contact with blacks.

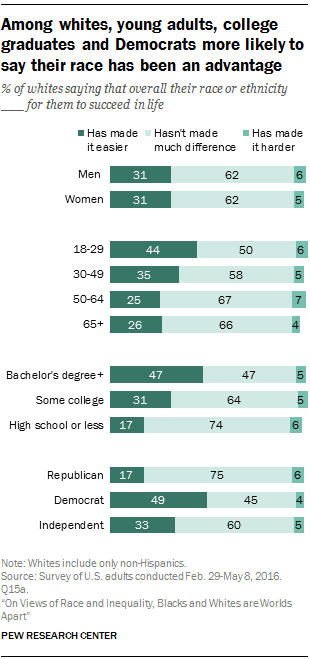

While some whites report being treated unfairly at times because of their race, the overall impact is relatively minor. Only 5% of whites say their race or ethnicity has made it harder for them to succeed in life. A majority of whites (62%) say their race hasn’t made much of difference in their ability to succeed, and 31% say their race has made things easier for them.

College-educated whites are especially likely to see their race as an advantage: 47% say being white has made it easier for them to succeed. By comparison, 31% of whites with some college education and 17% of those with a high school diploma or less say their race has made things easier for them. White Democrats (49%) are also among the most likely to say that their race or ethnicity has made it easier for them to get ahead in life.

For many blacks, the cumulative impact of discrimination has had a markedly negative impact on their lives. Four-in-ten blacks say their race has made it harder for them to succeed in life. Roughly half (51%) say their race hasn’t made a difference in their overall success, and just 8% say being black has made things easier.

There is a sharp educational divide among blacks on the overall impact their race has had on their ability to succeed. Fully 55% of blacks with a four-year college degree say their race has made it harder for them to succeed in life. Some 45% of blacks who attended college but did not receive a bachelor’s degree say the same. Among blacks with a high school education or less, a far lower share (29%) say their race has made it harder for them to succeed. A majority of this group (60%) say their race hasn’t made a difference.

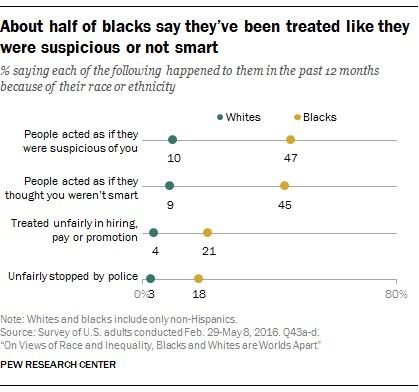

About half of blacks say people have acted like they were suspicious of them

Unfair treatment can come in different forms. Roughly half of blacks (47%) say that in the past 12 months someone has acted as if they were suspicious of them because of their race or ethnicity. Many blacks also report feeling like others have questioned their intelligence. Some 45% say that in the past 12 months people have treated them as if they were not smart because of their race or ethnicity.

Roughly one-in-five blacks (21%) say they have been treated unfairly by an employer in the past year because of their race or ethnicity, and a similar share (18%) report having been unfairly stopped by the police during this period.

Black men are more likely than black women to say that people have treated them with suspicion (52% vs. 44%). And they are more likely to say they have been unfairly stopped by the police (22% vs. 15%).

Being treated with suspicion and being treated as if they are not intelligent are more common experiences for black adults who attended college than for those who did not. For example, 52% of those with at least some college education say that, in the past 12 months, someone has treated them as if they thought they weren’t smart because of their race or ethnicity, compared with 37% of those with a high school diploma or less.

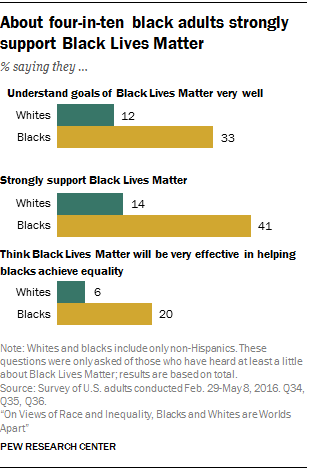

Among blacks, widespread support for the Black Lives Matter movement

Most blacks (65%) express support for the Black Lives Matter movement: 41% strongly support it, and 24% say they support it somewhat. Some 12% of blacks say they oppose Black Lives Matter (including 4% who strongly oppose it). Even so, blacks have somewhat mixed views about the extent to which the Black Lives Matter movement will be effective, in the long run, in helping blacks achieve equality. Most (59%) think it will be effective, but only 20% think it will be very effective. About one-in-five (21%) say it won’t be too effective or won’t be effective at all in the long run.

Blacks with a bachelor’s degree or more are among the most skeptical that the Black Lives Matter movement will ultimately help bring about racial equality. About three-in-ten (31%) of those with a bachelor’s degree or more education say that, in the long run, the movement won’t be too effective or won’t be effective at all, compared with about two-in-ten adults with less education.

Granted, many blacks are skeptical overall that the country will eventually make the changes needed to bring about racial equality. But even among those who think change will eventually come, only 23% say Black Lives Matter will be very effective in helping bring about equality.

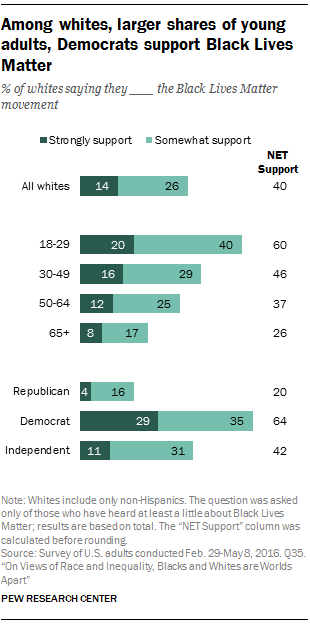

For their part, whites have mixed views of the Black Lives Matter movement. Four-in-ten whites say they support the movement (14% strongly support and 26% somewhat support). And about a third (34%) of whites say, in the long run, the Black Lives Matter movement will be at least somewhat effective in helping blacks achieve equality.

Young white adults are more enthusiastic about Black Lives Matter than middle-aged and older whites. Six-in-ten of those ages 18 to 29 say they support it, compared with 46% of whites ages 30 to 49, 37% of whites ages 50 to 64, and 26% of whites 65 and older. Young whites are also somewhat more likely than their older counterparts to say that the Black Lives Matter movement will be at least somewhat effective in the long run (47% vs. 37%, 32% and 26%, respectively).

Whites’ views on Black Lives Matter also differ significantly by party identification. Some 64% of white Democrats support the movement, including 29% who do so strongly. One-in-five white Republicans and 42% of white independents say they support the Black Lives Matter movement (4% of Republicans and 11% of independents strongly support it). White Democrats are also much more likely than Republicans and independents to say that the movement will ultimately be at least somewhat effective in bringing about racial equality (53% vs. 20% and 34%, respectively).

When asked how well they feel they understand the goals of the Black Lives Matter movement, blacks are much more likely than whites to say they understand it very or fairly well. Even so, about one-in-five blacks (19%) say they don’t have a good understanding of its goals, compared with 29% of whites. But general awareness of Black Lives Matter is widespread among whites and blacks: Overall, 81% of blacks and 76% of whites have heard at least a little about the movement, including about half or more of each group (56% and 48%, respectively), who say they have heard a lot.

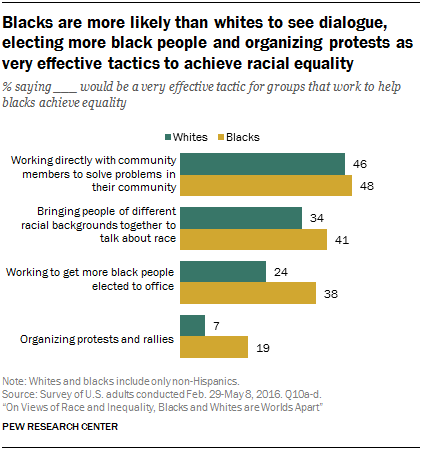

Many blacks and whites say community engagement is key to bringing about racial equality

More than four-in-ten blacks (48%) and whites (46%) say that working with community members to solve problems in their community would be a very effective tactic for groups striving to help blacks achieve equality. But the two groups disagree about the effectiveness of some other tactics.

In particular, while nearly four-in-ten (38%) black adults say working to get more black people elected to office would be very effective, just 24% of whites say the same. Blacks are also more likely than whites to say it would be very effective for groups working to help blacks achieve equality to bring people of different racial backgrounds together to talk about race (41% vs. 34%). Similarly, blacks see more value than whites in organizing protests and rallies, although relatively few blacks view this as a very effective way to bring about change (19% vs. 7% of whites).

The remainder of this report examines in greater detail the public’s views of the state of race relations and racial inequality in the U.S. Chapter 1 looks at some key demographic and economic indicators where blacks have made progress or lag behind other racial and ethnic groups. Chapter 2 focuses on views about the current state of race relations and its trajectory, as well as the job Obama has done on this issue. Chapter 3 examines the extent to which Americans think the country has made – or will eventually make – the changes necessary for blacks to achieve equal rights with whites. It also looks at perceptions about the way blacks and whites are treated across many realms of American life. Chapter 4 focuses on what the public sees as effective strategies for groups and organizations working to promote racial equality and explores attitudes toward the Black Lives Matter movement and other organizations that strive to bring about equality for black Americans. Chapter 5 looks at personal experiences with discrimination as well as perceptions about the impact race and gender have had in one’s life. Chapter 6 describes the outlook and experiences of blacks, whites and Hispanics, particularly as they relate to personal finances.

Other key findings

- About half (48%) of whites say they are very satisfied with the quality of life in their community, compared with about a third (34%) of blacks. This gap persists after controlling for income. For example, 57% of whites with an annual family income of $75,000 or more report that they are very satisfied with the quality of life in their community; just 38% of blacks in the same income group say the same.

- Blacks are far more likely than whites to say they have experienced financial hardship in the past 12 months. About four-in-ten (41%) blacks say they have had trouble paying their bills, and about a quarter (23%) say they have gotten food from a food bank or food pantry during this period. Among whites, 25% say they have struggled to pay their bills, and 8% report having sought out food from a food bank in the past 12 months.

- Black men are far more likely than white men to say their gender has made it harder for them to get ahead in life (20% vs. 5%, respectively). Among women, similar shares of blacks (28%) and whites (27%) say their gender has set them back.

- About eight-in-ten (81%) blacks say they feel at least somewhat connected to a broader black community in the U.S., including 36% who feel very connected. Blacks who feel a strong sense of connection to a broader black community are more likely than those who don’t to say that in the past 12 months they have made a financial contribution to, attended an event sponsored by, or volunteered their time to a group or organization working specifically to improve the lives of black Americans.

- Majorities of blacks say the NAACP (77%), the National Urban League (66%) and the Congressional Black Caucus (63%) have been at least somewhat effective in helping blacks achieve equality in this country. Only about three-in-ten or fewer say each of these groups has been very effective, likely reflecting, at least in part, the widespread view among blacks that the country has work to do for blacks to achieve equal rights with whites.

References to whites, blacks and Asians include only those who are non-Hispanic, unless otherwise noted, and identify themselves as only one race. Hispanics are of any race. In Chapter 1, references to whites and blacks for survey years prior to 1971 include Hispanics.

Throughout this report, references to college graduates or people with a college degree comprise those with a bachelor’s degree or more. “Some college” refers to those with a two-year degree or those who attended college but did not obtain a degree. “High school” refers to those who have attained a high school diploma or its equivalent, such as a General Education Development (GED) certificate.

Interactive How blacks and whites view the state of race in America

Interactive How blacks and whites view the state of race in America