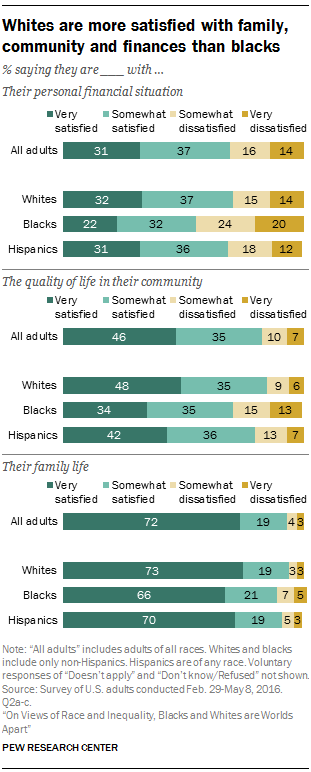

The outlook and experiences of black and white adults, particular as they relate to personal finances, differ widely. Blacks are more likely than whites to express dissatisfaction with their financial situation, and to say they have struggled to pay the bills and borrowed money from – or loaned it to – friends and family in the past 12 months. Blacks are also less satisfied than whites with the quality of life in their communities and, though to a lesser extent, with their family life.

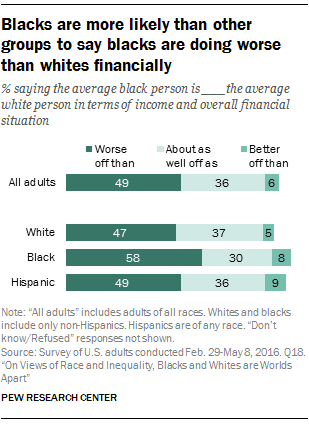

But blacks and whites don’t differ just in the way they describe their personal experiences. Blacks are also significantly more likely than whites to say that blacks, as a group, are worse off than whites today in terms of their income and overall financial situation; about six-in-ten (58%) black adults say this, compared with about half (47%) of whites. Still, more whites say blacks are worse off than say they are doing about as well (37%) as whites financially. Few of either group say blacks are better off than whites financially.

Whites and blacks have different outlooks on some key aspects of life

Across three measures – satisfaction with the quality of life in their community, personal finances, and family life – whites are more likely than blacks to say they are very satisfied. Differences in outlook are particularly pronounced in regards to one’s community; about half (48%) of whites say they are very satisfied with the quality of life in their community, compared with about a third (34%) of blacks. By a margin of 32% to 22%, a larger share of whites than blacks say they are very satisfied with their personal financial situation. And while majorities of both groups express high levels of satisfaction with their family life, whites are more likely to do so (73% vs. 66% of blacks).

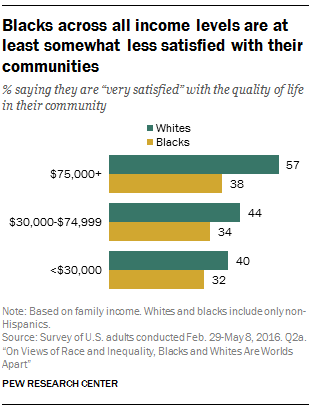

For whites, satisfaction in these three areas is tied to income. The link between outlook and income is less consistent among blacks – higher-income blacks are more likely than those with lower incomes to say they are very satisfied with their personal finances and family life, but they are not necessarily more likely to be satisfied with the quality of life in their community.

Roughly six-in-ten (57%) whites with annual family incomes of at least $75,000 say they are very satisfied with the quality of life in their community, compared with 44% of whites with incomes of $30,000 to $74,999 and 40% of those with incomes of less than $30,000. Among blacks, however, similar shares across income groups say they are very satisfied with this aspect of their life (38%, 34% and 32%, respectively). In each income group, blacks are at least somewhat less likely than their white counterparts to express high levels of satisfaction in the quality of life in their community, and this gap is particularly pronounced between blacks and whites with higher incomes (19 percentage points).

One possible reason for this gap: Researchers at Stanford University found that even among blacks and whites with similar incomes, blacks live in poorer quality neighborhoods in terms of characteristics like schools, child care, recreational spaces and transportation. Furthermore, they found that middle-income black families typically live in neighborhoods with lower average incomes than that of the typical low-income white family. 19

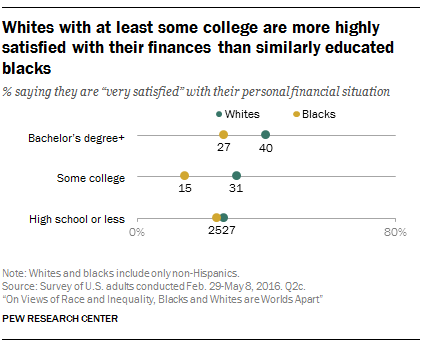

Perhaps not surprisingly, high levels of satisfaction with one’s finances are also tied to income; among blacks and whites, those with higher annual family incomes are more likely than those with lower incomes to say they are very satisfied. Among whites, satisfaction with personal finances is also linked to higher levels of educational attainment, but the same is not the case for blacks.

Whites with at least some college experience are more likely than their black counterparts to express high levels of satisfaction with their personal financial situation. There is a 13 percentage point gap in the share of white and black college graduates who say they are very satisfied with their finances (40% vs. 27%) and a 16 percentage point gap in the share of whites and blacks with some college (31% vs. 15%) who say the same. The experiences of whites and blacks with only a high school diploma or less are more similar (27% and 25% are very satisfied, respectively), though whites are more likely than blacks in this group to be at least somewhat satisfied with their financial situation.

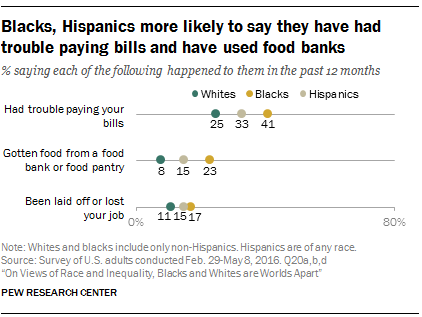

Blacks and Hispanics face more financial hardship than whites

Blacks and Hispanics are more likely than whites to report that they have experienced financial hardship over the past year. For example, some 41% of black adults and 33% of Hispanics say they have had trouble paying their bills, compared with 25% of whites. And blacks (23%) and Hispanics (15%) are much more likely than whites (8%) to have sought out food from a food bank over the past year.

The gap between whites and blacks is somewhat narrower on recent job losses. Whites are slightly less likely than blacks (11% vs. 17%) to say they have been laid off or have lost their job over the past year. Some 15% of Hispanics say this happened to them.

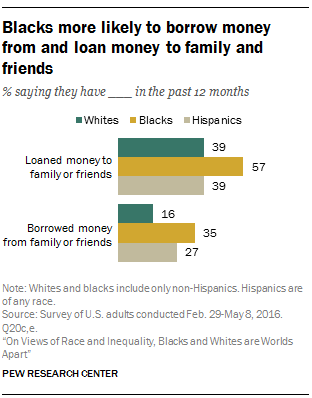

Black Americans are particularly likely to have loaned – and borrowed – money

Exchanges of money between family and friends are particularly common among black Americans. Some 57% of black adults say they have loaned money to family or friends over the past year, and 35% say they have borrowed money. By comparison, just 39% of white adults say they loaned money to family or friends and 16% say they borrowed money in the past year.

Blacks across all income levels are substantially more likely than whites in the same income bracket to say they have loaned money to or borrowed it from family or friends. For example, among those with family incomes upwards of $75,000, blacks are 25 percentage points more likely than whites to say they have loaned money (61% vs. 36%) and 13 percentage points more likely to say they have borrowed money (20% vs. 7%). And among those with family incomes of less than $30,000, blacks are 16 percentage points more likely than whites to have loaned money (56% vs. 40%) and 17 percentage points more likely to have borrowed it (45% vs. 28%).

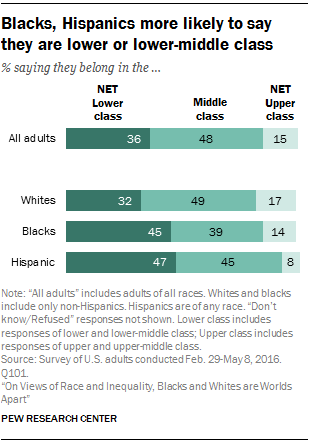

Blacks less likely than whites to consider themselves “middle class”

Views of personal finances are also reflected in the social class in which Americans place themselves. Overall, about half of Americans describe themselves as being in the middle class (48%), while 36% say they are in the lower-middle or lower class and 15% place themselves in the upper-middle or upper class. Similar shares of white (17%) and black (14%) adults identify as upper class, but a larger share of whites than blacks say they are middle class (49% vs. 39%). And a far lower share of whites than blacks place themselves in the lower class (32% vs. 45%). Among Hispanics, 8% say they are in the upper class, 45% say they are middle class, and about half (47%) describe themselves as part of the lower class.

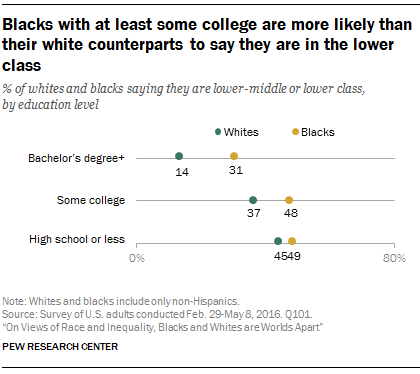

To some extent, differences in the way blacks and whites describe their social class can be attributed to differences in educational attainment across the two groups. Whites are more likely than blacks to have college degrees (see Chapter 1), and those with college degrees are more likely than those with less education to say they are middle or upper class. For example, among all U.S. adults with a bachelor’s degree, 28% say they are in the upper class, 54% say they are middle class, and 17% describe themselves as lower class, compared with 10%, 49%, and 39%, respectively, of those with some college and 10%, 41%, and 48%, respectively, of those with a high school education or less.

Still, racial differences in social class identification persist even after controlling for levels of education – except among those with a high school diploma or less education. Black college graduates, as well as those who attended college but did not receive a bachelor’s degree, are more likely than whites with similar levels of education to say they are in the lower class. About three-in-ten (31%) blacks with a college degree describe themselves as lower class, twice the share of white college graduates (14%) who do the same. And while about half (48%) of blacks with some college say they are in the lower class, a smaller share (37%) of whites with comparable levels of education say this.

About half of U.S. adults say blacks are worse off financially than whites

Racial gaps in financial satisfaction and reported financial hardship reflect decades-old gaps in financial well-being between blacks and whites (see Chapter 1 for an analysis of data from the U.S. Census Bureau). Still, many Americans – including at least three-in-ten whites (37%), blacks (30%), and Hispanics (36%) – believe blacks are about as well off as whites financially.

Blacks are more likely than whites and Hispanics to say the average black person is worse off than the average white person in terms of income and overall financial situation; about six-in-ten (58%) black adults say this, compared with about half of whites (47%) and Hispanics (49%). Few adults in each group say blacks are doing better than whites.

College-educated adults are more likely than those with less education to see financial inequality, and this is true for both black and white adults. Among blacks, 81% of those with a bachelor’s degree or more and 61% of those with some college education say the average black person is worse off financially than the average white person, compared with just 46% of blacks with a high school education or less.

For whites, the educational pattern is similar: 66% of whites with at least a bachelor’s degree and 47% with some college say blacks are worse off financially, compared with 29% of whites with at most a high school diploma. The pattern by family income largely mirrors that by educational attainment.

Interactive How blacks and whites view the state of race in America

Interactive How blacks and whites view the state of race in America