There’s no consensus among American adults about the state of race relations in the U.S.: 48% say race relations are generally bad, and 44% say they are generally good. Similarly, when asked about the amount of attention paid to race and racial issues in the country these days, about as many say there is too much (36%) as say there is too little (35%) attention, while 26% say there is about the right amount of attention paid to these issues.

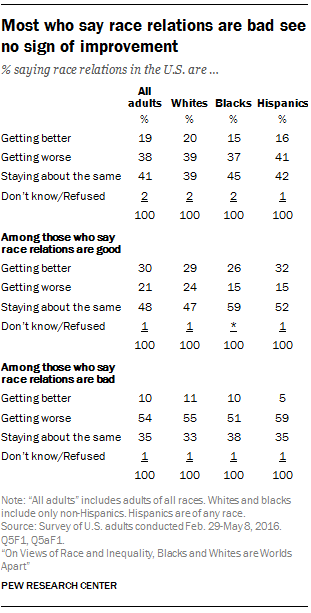

Overall, relatively few Americans think race relations are headed in a positive direction. Only 19% say race relations are improving, while about four-in-ten say they are getting worse (38%), and a similar share say things are staying about the same (41%). Those who already think race relations are bad are particularly likely to say things are getting even worse.

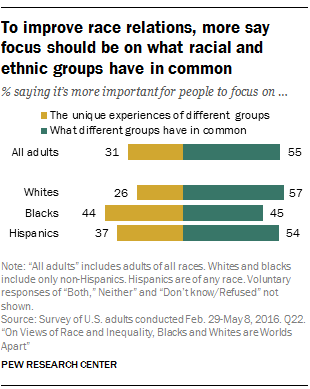

And there is no widespread agreement on how to make things better. When asked about the best approach to improving race relations, 55% of Americans say it’s more important for people to focus on what different racial and ethnic groups have in common, while fewer (31%) say the focus should be on what makes each group unique.

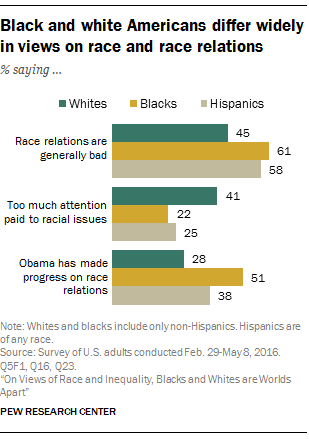

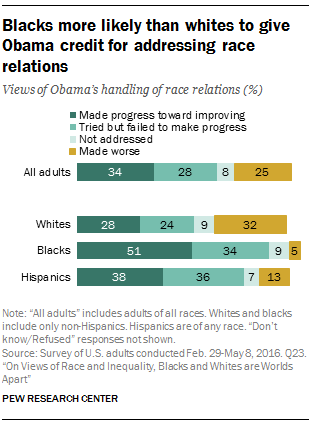

Opinions on these fundamental questions about race relations– where we are, how they can be improved, and how much attention the issue warrants – are sharply divided along racial lines. Blacks and whites are also divided in their views of Obama’s handling of race relations. Among whites, about as many say the president has made progress toward improving race relations (28%) as say he has made things worse (32%). In contrast, 51% of blacks say Obama has made progress on this issue; just 5% believe he has made race relations worse.

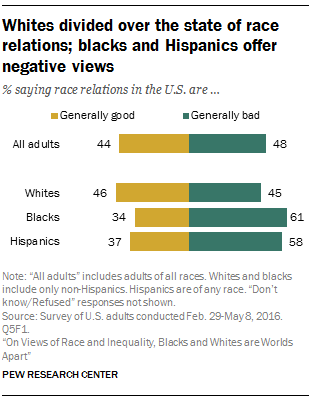

Blacks and Hispanics more likely to say race relations are bad

Views about the current state of race relations vary considerably across racial and ethnic lines. While whites are about equally likely to say race relations are good (46%) as to say they are bad (45%), the assessments of blacks and Hispanics are decidedly negative. About six-in-ten (61%) blacks say race relations in this country are bad, while 34% say they are good. Similarly, far more Hispanics say race relations are bad (58%) than say they are good (37%).

Roughly half or more of black adults across demographic groups express negative views about the current state of race relations. Among whites, views are also fairly consistent across gender, age, education and income groups, but opinions divide along political lines. About six-in-ten (59%) white Democrats say race relations in the U.S. are generally bad, while about a third (34%) say they’re good. In contrast, white Republicans are about evenly divided between those who say race relations are bad (46%) and those who say they’re good (48%). Among white independents, 49% offer positive assessments, while 39% say race relations are bad.

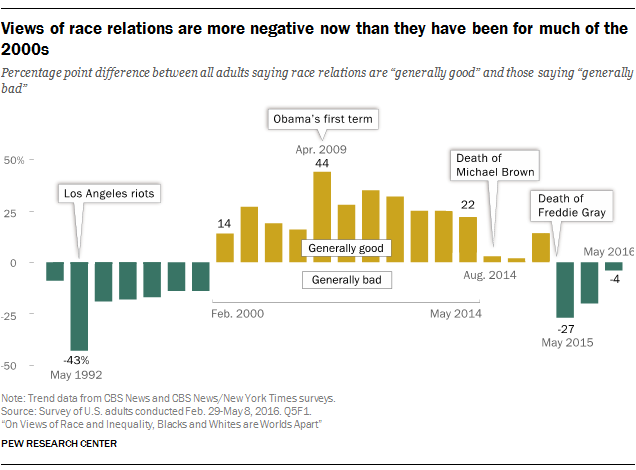

Overall, views of race relations are more positive now than they were a year ago. In May 2015, following unrest in Baltimore over the death of Freddie Gray, a black man who died while in police custody, far more Americans said race relations were bad (61%) than said they were good (34%), according to a CBS News/New York Times poll. At that time, whites (62%) were about as likely as blacks (65%) to say race relations were generally bad.

Even so, the public’s views of race relations are more negative now than they have been for much of the 2000s. Between February 2000 and May 2014, by double-digit margins, more said race relations were good than said they were bad. By August 2014, after the death of Michael Brown, an unarmed black 18-year-old shot and killed by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, opinions had changed significantly: 47% described race relations in the U.S. as generally good and

44% as generally bad.

Views of the state of race relations were particularly negative after the Los Angeles riots in 1992. In May 1992, about seven-in-ten (68%) Americans, including 67% of whites and 75% of blacks, said race relations were generally bad.

Few say race relations are improving

About one-in-five (19%) Americans say race relations in the U.S. are getting better, while about four-in-ten (38%) say they are getting worse and about as many (41%) say they are staying about the same.

Those who say race relations are currently bad are particularly pessimistic: 54% say race relations are getting even worse, and 35% don’t see much change. Only one-in-ten of those who say race relations are bad believe they are improving. These views are shared about equally by whites, blacks and Hispanics who offer negative assessments of the current state of race relations.

Among those who say race relations are good, three-in-ten say they are getting better and roughly half (48%) say they are staying about the same; 21% say race relations are getting worse. Whites who say race relations are currently good offer a somewhat more negative assessment of where the country is headed on this issue than do blacks and Hispanics who say race relations are good. About a quarter (24%) of whites who say race relations are good believe they are getting worse, compared with 15% of blacks and Hispanics who feel that way.

More say focus should be on what different groups have in common

Far more Americans say that when it comes to improving race relations, it’s more important for people to focus on what different racial and ethnic groups have in common (55%) than say it’s more important to focus on the unique experiences of different racial and ethnic groups (31%).

This is particularly the case among whites, who are about twice as likely to say the focus should be on what different groups have in common (57%) rather than what makes different groups unique (26%). Hispanics also share this view by a margin of 54% to 37%.

Blacks are more evenly divided: 44% say it’s more important for people to focus on what makes different racial and ethnic groups unique, while roughly the same share (45%) say the focus should be on what different groups have in common.

For the most part, the views of blacks and whites about the best approach to improving race relations do not vary considerably across demographic groups. For example, across educational groups – from those with a high school diploma or less to those with a bachelor’s degree – blacks divide in roughly the same way on this question, and the same is true across educational groupings for whites.

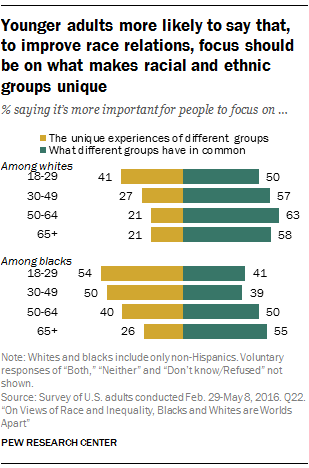

There are significant age gaps, however, when it comes to opinions about focusing on differences vs. similarities. Among white adults, those younger than 30 are more likely than older whites to say that, when it comes to improving race relations, it’s more important for people to focus on the unique characteristics of each group; about four-in-ten (41%) whites ages 18 to 29 say this, compared with 27% of whites ages 30 to 49 and about one-in-five of those ages 50 and older (21%).

Age is also linked to black adults’ views about the best approach to improving race relations, although, among this group, the divide is between those younger than 50 and those who are 50 or older. Among blacks ages 18 to 49, more say the focus should be on what makes each racial and ethnic group unique (54% among those ages 18 to 29 and 50% among those ages 30 to 49). Among older blacks, particularly those ages 65 and older, more say the focus should be on what different racial and ethnic groups have in common.

Blacks and whites differ over the amount of attention paid to race and racial issues

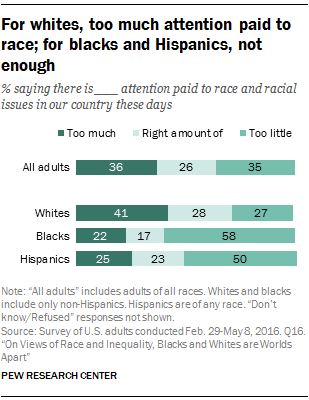

When asked if they think the amount of attention paid to race and racial issues in our country today is too much, too little or about right, Americans are divided: 36% say there is too much and about as many (35%) say there is too little. Roughly a quarter (26%) say the amount of attention paid to these issues is about right.

Blacks’ and whites’ views on this issue are in sharp contrast. Blacks are about twice as likely as whites to say too little attention is paid to race and racial issues (58% vs. 27%). And while only 22% of blacks say there is too much focus on race, 41% of whites say this is the case. Among Hispanics, half think too little attention is paid to race and racial issues, while 25% say too much attention is paid to those issues and 23% say it is about the right amount.

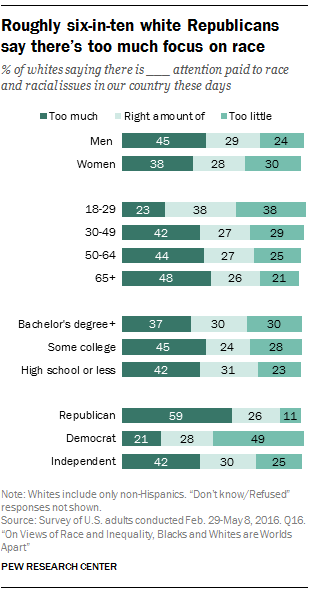

For whites, views about the amount of attention given to race and racial issues are strongly linked to partisanship. About six-in-ten (59%) white Republicans say too much attention is paid to these issues these days; just 11% say there is too little attention, and 26% say the amount of attention is about right. In contrast, about half of white Democrats (49%) say not enough attention is being paid to race and racial issues, while 21% say the amount is too much and 28% say it is about right. Still, white Democrats are far less likely than black Democrats (62%) to say too little attention is being paid to these issues.

Whites’ opinions about how much focus there is on race and racial issues in the country today are also linked to age. Whites who are younger than 30 are far less likely than older whites to say there is too much focus on race; about a quarter (23%) of whites ages 18 to 29 say this, compared with at least four-in-ten whites ages 30 to 49 (42%), 50 to 64 (44%) and 65 or older (48%). There are no significant demographic differences among blacks on this question.

Most say Obama at least tried to improve race relations

In the days following Barack Obama’s election in 2008, voters were somewhat optimistic that the election of the nation’s first black president would lead to better race relations. Today, as Obama finishes his second term, about a third (34%) of Americans say Obama has made progress toward improving race relations, and about three-in-ten (28%) say the president has tried but failed to make progress in this area. A sizable share (25%) say he has made race relations worse, while 8% say Obama has not addressed race relations.

Assessments of Obama’s performance on race relations vary considerably along racial and ethnic lines. About half (51%) of black Americans think the president has made progress toward improving race relations; 34% say he tried but failed to make progress. Very few blacks say Obama made race relations worse (5%) or that he didn’t address the issue (9%).

Among whites, however, about a third (32%) say the president has made things worse when it comes to race relations; 28% say Obama has made progress toward improving race relations and 24% say he tried but failed. Hispanics’ assessments of Obama’s performance on race relations are not as negative as those of whites, but are also not as positive as those offered by blacks. Roughly four-in-ten (38%) Hispanics say the president made progress toward improving race relations, and about as many (36%) say he has tried but failed to make progress; 13% of Hispanics say he has made things worse. About one-in-ten (9%) blacks and 7% of Hispanics say Obama has not addressed race relations.

Among blacks, opinions about Obama’s handling of race relations vary primarily along educational lines. While about half of black Americans with some college (52%) or with a high school education or less (54%) say the president has made progress toward improving race relations, fewer among those with a bachelor’s degree (40%) say Obama has had success in this area. Still, at least eight-in-ten black Americans across educational attainment say the president has at least tried to make progress toward improving race relations, even if he hasn’t necessarily succeeded.

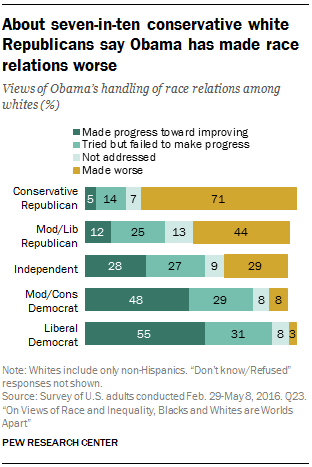

Assessments of Obama among whites are strongly linked to partisanship and ideology. About six-in-ten (63%) white Republicans say the president has made race relations worse, a view that is shared far more widely by white Republicans who describe their political views as conservative (71%) than among Republicans who say they are politically moderate or liberal (44%). In contrast, about half (52%) of white – and black (55%) – Democrats, including somewhat similar shares of those who are liberal and moderate or conservative, say the president has made progress toward improving race relations.

Far more blacks than whites say they talk about race-related topics with family, friends

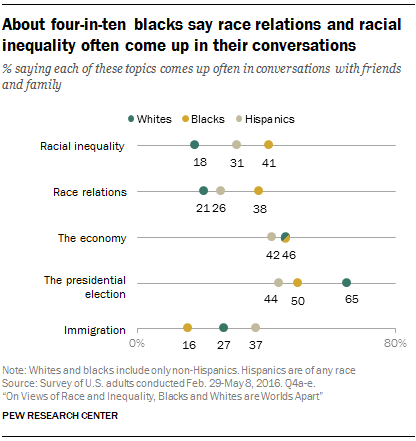

For blacks, far more than for whites, conversations about race are fairly commonplace. Overall, about a quarter of Americans say they often talk about race relations or racial inequality with friends and family, far less than the share saying they talk about the presidential election campaign (59%) or the economy (45%) with the same frequency. 16 About a quarter (27%) say immigration is often a topic of conversation with friends and family.

Blacks are about twice as likely as whites to say the topics of racial inequality and race relations often come up in conversations with friends and family. About four-in-ten black adults say racial inequality (41%) and race relations (38%) are frequent topics of conversation, compared with about one-in-five whites. Among Hispanics, about three-in-ten (31%) say they often talk about racial inequality and about a quarter (26%) say they often talk about race relations.

In contrast, about the same shares of whites (46%), blacks (46%) and Hispanics (42%) say they often talk to friends and family about the economy, while Hispanics are more likely than the other two groups to say immigration is a frequent topic of conversation for them (37% vs. 27% of whites and 16% of blacks).

Blacks and whites offer different assessments of their interactions with people of the other race

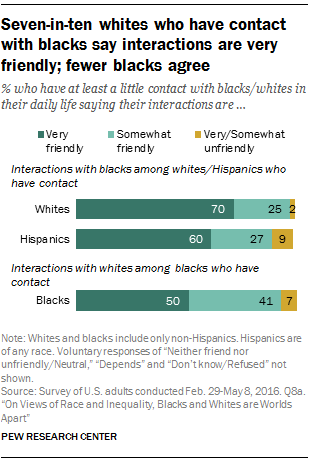

Most whites who have some daily contact with people who are black describe their interactions as mainly positive. Blacks give a somewhat less positive assessment of their contact with whites. Fully 70% of whites who have a least a little bit of contact with blacks characterize their interactions as very friendly. Black adults are 20 percentage points less likely to describe interactions with whites that way: half of those who have at least a little contact with whites in their daily life describe these interactions as very friendly, while about four-in-ten (41%) would call them “somewhat friendly.” Relatively few in either group would go so far as to call their interactions “unfriendly” (2% among whites and 7% among blacks).

The survey also asked Hispanics about their interactions with people who are black. Among the 86% of Hispanics who have any amount of contact with blacks, 60% say these interactions are generally very friendly; 27% say they are somewhat friendly, and 9% describe their interactions with blacks as unfriendly. About one-in-eight (13%) Hispanics say they have no contact with people who are black. Hispanics who have a lot of contact with blacks are far more likely than those who have some or only a little contact to say these interactions are very friendly; about three-quarters (73%) of Hispanics who have a lot of contact with blacks say this is the case, compared with 58% of those who have some contact and 45% of those who have only a little contact with people who are black.

Overall, 66% of blacks say they have a lot of contact with whites, while 20% have some contact, and 12% have a little contact; just 2% of blacks say they have no contact at all with people who are white. Not surprising, since blacks are a far smaller share of the population, far fewer whites (38%) say they have a lot of contact with people who are black, while 35% say they have some contact and 20% say they have only a little contact; 6% of whites say they have no contact with blacks. Southern whites (50%) are far more likely than whites in the Northeast (36%), Midwest (33%) and West (29%) to say they have a lot of contact with people who are black.

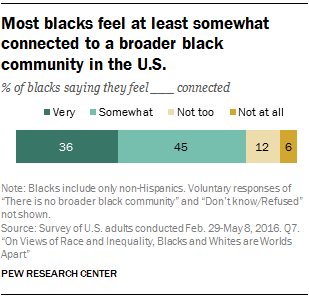

Roughly a third of blacks say they feel very connected to a broader black community

About eight-in-ten (81%) black adults say they feel at least somewhat connected to a broader black community in the U.S., including 36% who feel very connected. About one-in-five say they don’t feel too (12%) or at all (6%) connected to a broader black community in the U.S.

Blacks across demographic groups, including men and women, young and old, and across education and income levels, are about equally likely to say they feel very connected to a broader black community. However, those with less education and lower incomes are more likely than those with a bachelor’s degree and annual family incomes of at least $30,000 to say they don’t feel too or at all connected. About one-in-five blacks with only some college (18%) or with a high school education or less (20%) feel disconnected from a broader black community, compared with 11% of black college graduates. And while 22% of blacks with family incomes below $30,000 say they don’t feel too or at all connected to a broader black community, fewer among those with incomes between $30,000 and $74,999 (13%) or higher (12%) say the same.

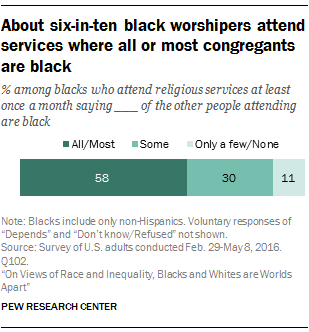

Blacks who say they regularly attend predominantly black churches are among the most likely to feel connected to a broader black community. Among those who attend religious services at least once a month and who say all or most of the congregants are black, 48% say they feel very connected. By comparison, 35% of black churchgoers who say some or only a few of the people with whom they attend services are black feel the same sense of connectedness.

Overall, 58% of black adults say they attend religious services at least monthly, including 39% who do so at least once a week and 19% who attend once or twice a month; an additional 17% of black adults say they attend a few times a year, while about a quarter say they do so only seldom (13%) or never (11%). By this measure, blacks are significantly more likely than whites to attend religious services regularly; 44% of whites say they attend at least monthly, while 17% say they do so a few times a year and 39% say they seldom or never attend religious services. 17

About six-in-ten (58%) black adults who say they attend church at least monthly report that all or most of the other people attending are black. Three-in-ten say some are black and 11% say only a few or none are black.

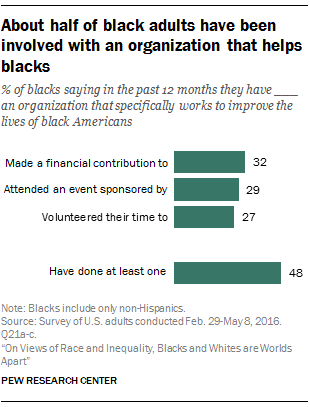

About half of blacks have made a financial contribution, attended an event, or volunteered their time to an organization working to improve the lives of black Americans

Blacks who have a strong sense of connection to a broader black community are more likely than those who don’t feel strongly connected to say they are actively involved with groups or organizations that specifically work to improve the lives of black Americans. Overall, about three-in-ten blacks say they have made a financial contribution to (32%), attended an event sponsored by (29%), or volunteered their time to (27%) such a group in the past 12 months. Roughly half (48%) of black Americans say they have done at least one of these activities.

Among blacks who say they feel very connected to a broader black community, about six-in-ten (58%) say they have done at least one of these activities, compared with 45% of those who say they feel somewhat connected and 35% of those who say they feel not too connected or not at all connected to a broader black community.

Looking at each activity, roughly four-in-ten (43%) blacks who feel very connected to a broader black community report having made a financial contribution to a group or organization that works to improve the lives of black Americans in the past 12 months, compared with 28% of those who feel somewhat connected and 22% who don’t feel too or at all connected to a broader black community. Similarly, those who feel very connected are more likely than those who feel somewhat or even less connected to say they have attended an event sponsored by this type of group (38% vs. 27% and 16%, respectively) or have volunteered their time (33% vs. 25% and 19%).

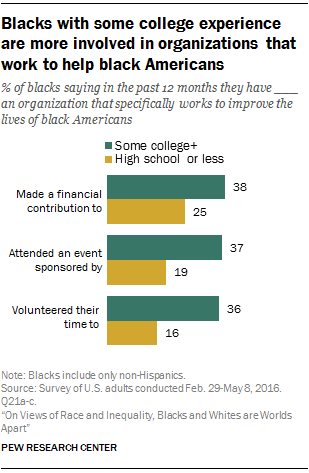

For the most part, involvement with organizations that specifically work to improve the life of black Americans doesn’t vary significantly across demographic groups. But blacks with at least some college experience are more likely than those with a high school diploma or less to say they have made a financial contribution (38% vs. 25%), attended an event (37% vs. 19%) or volunteered their time (36% vs. 16%) to this type of organization in the past 12 months.

Interactive How blacks and whites view the state of race in America

Interactive How blacks and whites view the state of race in America