In 2014, as Pew Research Center prepared to conduct the first major study of the views of multiracial Americans—a group that, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, is poised to triple by 2060—we faced a fundamental and unavoidable methodological challenge: how to define and measure the concept “multiracial” in a public opinion survey context.1

Racial identity is far from a straightforward concept, and when multiple strands of identity come together this has the potential to increase the complexity. An individual’s racial self-identity may take into account a range of factors beyond genealogy, including family ties, physical appearance, culture and how others perceive them. In other words, being multiracial is more than just a straightforward summation of the races in an individual’s family tree.2

Consider, for example, a man whose mother is Asian and whose father is white. This may seem like someone who could easily be categorized as multiracial. But if this man was raised with little or no interaction with his white relatives or had experiences that were more closely aligned with those of the Asian community, he may well select “Asian” and nothing else when describing his race. Furthermore, some adults may have relatives of different races farther back in their family tree. While some people may think to include a more distant relative of a different race when asked about their racial background, others may not, even if they are aware of their family history.

With this in mind, we set out to test six different ways of defining a population of mixed-race adults to survey, using as our primary vehicle Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), a probability-based, nationally representative online panel of adults in the United States. We tested these different approaches with impaneled individuals who participated in more than one Pew Research Center survey, allowing us to examine how the same individual might have changed his or her responses depending on the question asked.

In this report, we share the results of these six survey experiments with a focus on the ways in which the different wordings of the stem, different response options and different modes used impacted the projected size of the U.S. multiracial population. We also look at the consistency in selecting two or more races across different measures at the individual level, as well as how estimates of specific subgroups of multiracial adults—most notably white and American Indian biracial adults—vary by question type.

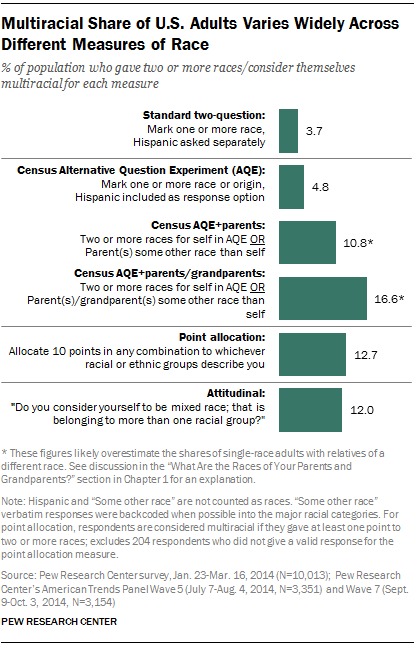

Standard two-question measure. The first measurement effort was the standard two-question race and ethnicity format included on most Pew Research Center polls. Similar to the method currently employed by the Census Bureau and many other survey researchers, it asks a respondent to select one or more races, with a separate question measuring Hispanic ethnicity. This produced our baseline estimate that 3.7% of American adults are mixed race, defined as selecting two or more races (defined as: white, black, Asian, American Indian/Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander; Hispanic and “some other race” are not included as races).3

Standard two-question measure. The first measurement effort was the standard two-question race and ethnicity format included on most Pew Research Center polls. Similar to the method currently employed by the Census Bureau and many other survey researchers, it asks a respondent to select one or more races, with a separate question measuring Hispanic ethnicity. This produced our baseline estimate that 3.7% of American adults are mixed race, defined as selecting two or more races (defined as: white, black, Asian, American Indian/Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander; Hispanic and “some other race” are not included as races).3

Census Alternative Questionnaire Experiment measure. We then tested a question being considered for the 2020 decennial census, in which the Hispanic origin response option is included with the racial categories in a “mark one or more” format. Using this measure, called the Alternative Questionnaire Experiment (AQE), we found that 4.8% of adults reported two or more races (not including Hispanic or some other race).

Census AQE measure with parents’ races. Some researchers have argued that the population with a mixed racial background is likely broader than the share of adults who report two or more races when asked to identify their own race in a “mark one or more” format. One of the ways we tested this theory was by exploring the race and ethnicity of respondents’ parents and grandparents. First, we asked those who chose only one race in the AQE measure whether either their mother or father was “some other race or origin” than the race they selected for themselves. This roughly doubled the share reporting a multiracial background to 10.8%.

Census AQE measure with parents’ and grandparents’ races. For those who said they did not have a parent of a different race, we asked whether any of their grandparents were “some other race or origin” than their own, which increased the share indicating a multiracial background to 16.6%. As discussed below, because of the way the follow-up questions were worded, we believe the share of single-race adults indicating that they have a parent or grandparent of a different race overestimates the multiracial population.

Point allocation measure. Next, we tested an experimental measure developed by University of California, Berkeley political scientist Taeku Lee in which respondents are given 10 “identity points” and asked to allocate them across different racial and ethnic categories however they see fit. For example, if they think of themselves as half white and half black, they could allocate five points to each, but if they think of themselves as mostly white, but had a black ancestor, they could allocate nine points to white and one point to black. This measure was developed to increase the share of adults reporting two or more races, and the Pew Research Center analysis finds that it does compared with the “mark one or more” approaches—some 12.7% of adults gave points to two or more races using this measure.

Attitudinal measure. Finally, we asked people directly, “Do you consider yourself to be mixed race; that is, belonging to more than one racial group?” Taking this approach, 12.0% of adults identified themselves as multiracial.

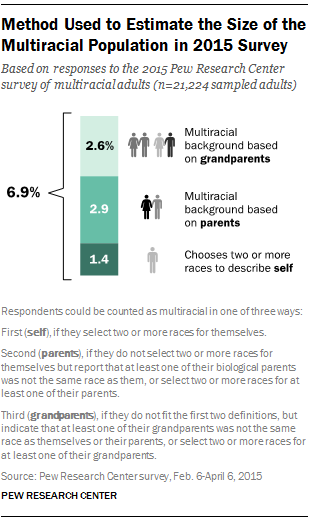

In the end, after assessing the strengths and weaknesses of each approach, we decided to cast a wide net in the 2015 survey of multiracial Americans by asking people to report their own race(s) or ethnicity using the AQE measure, as well as asking a revised version of the parent and grandparent follow-ups, in which we asked the specific race(s) and ethnicity of their biological parents, grandparents and earlier ancestors in a parallel format to the AQE measure. For the Pew Research Center analysis, we considered someone to be multiracial if their background included two or more races (not including Hispanic) when their own, their parents’ and their grandparents’ races were taken into account. This resulted in our estimate that 6.9% of American adults are multiracial. (Had the races of great-grandparents and earlier ancestors been taken into account, that estimate would have risen to 13.1%.)

In the end, after assessing the strengths and weaknesses of each approach, we decided to cast a wide net in the 2015 survey of multiracial Americans by asking people to report their own race(s) or ethnicity using the AQE measure, as well as asking a revised version of the parent and grandparent follow-ups, in which we asked the specific race(s) and ethnicity of their biological parents, grandparents and earlier ancestors in a parallel format to the AQE measure. For the Pew Research Center analysis, we considered someone to be multiracial if their background included two or more races (not including Hispanic) when their own, their parents’ and their grandparents’ races were taken into account. This resulted in our estimate that 6.9% of American adults are multiracial. (Had the races of great-grandparents and earlier ancestors been taken into account, that estimate would have risen to 13.1%.)

The remainder of this report will discuss in detail the various methods Pew Research Center tested to measure respondents’ racial backgrounds, including exact question wording, as well as an assessment of the resulting racial composition and of the challenges or concerns that each question elicits. Furthermore, because these questions were asked of the same individuals in different interviews, we are also able to examine whether the same individual changed his or her responses depending on the type of question asked. This report will look at the consistency in selecting two or more races at the individual level across the different methods, including among various multiracial subgroups. A more detailed breakdown of the racial composition of the adult population captured by the different measures, as well as a comparison of other demographics of the multiracial population captured by each measure, can be found in the tables in Appendix A.