The Growing Population of Older People in the U.S., Germany and Italy

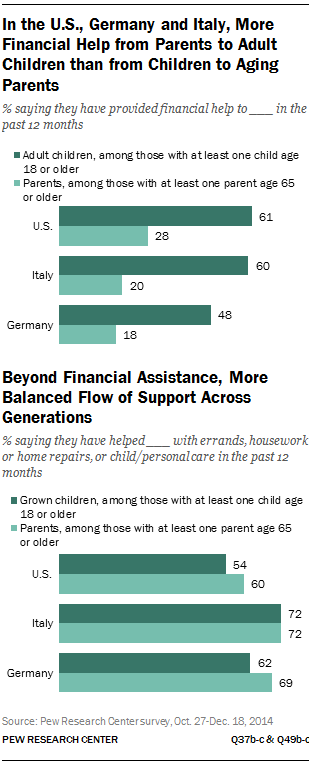

The United States is turning gray, with the number of people ages 65 and older expected to nearly double by 2050. This major demographic transition has implications for the economy, government programs such as Social Security and families across the U.S. Among adults with at least one parent 65 or older, nearly three-in-ten already say that in the preceding 12 months they have helped their parents financially. Twice that share report assisting a parent with personal care or day-to-day tasks. Based on demographic change alone, the burden on families seems likely to grow in the coming decades.

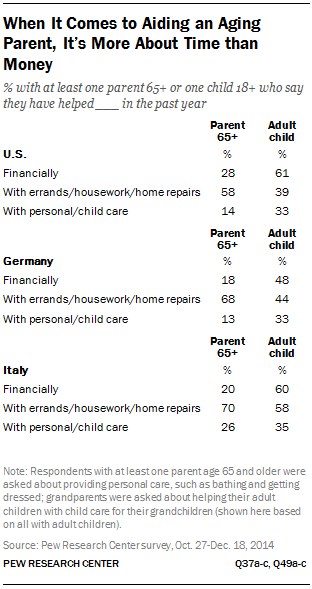

Germany and Italy, two of the “oldest” nations in the world, after only Japan, are already where the U.S. will be in 2050: a fifth of the population in each country is age 65 or older. Compared with the U.S. today, a higher share of adults in Germany and Italy report helping their aging parents with basic tasks, and more in Italy have also provided personal care. However, in both countries, fewer adults than in the U.S. say they have provided financial assistance to their aging parents.

The latter difference underscores that, while Germany and Italy may provide a window into the demographic future of the United States, cultural and political factors nonetheless distinguish the three countries. Nothing speaks to this more than the fact that, compared with Americans, twice as many Germans and even more Italians think the government should bear the greatest responsibility for people’s economic well-being in their old age. By contrast, in the U.S. a majority say that families or individuals themselves should see to the well-being of seniors.

The latter difference underscores that, while Germany and Italy may provide a window into the demographic future of the United States, cultural and political factors nonetheless distinguish the three countries. Nothing speaks to this more than the fact that, compared with Americans, twice as many Germans and even more Italians think the government should bear the greatest responsibility for people’s economic well-being in their old age. By contrast, in the U.S. a majority say that families or individuals themselves should see to the well-being of seniors.

These are among the key findings from a new survey by the Pew Research Center that compares the way families in the U.S., Germany and Italy are coping as more people enter their senior years and eventually require assistance. Based on interviews with at least 1,500 adults ages 18 and older in each country, the survey also finds that many families are facing the dual challenge of caring for aging parents while also supporting adult children. In the U.S., Germany and Italy, about half or more of adults who have at least one child 18 years of age or older say they have provided financial help to an adult child in the 12 months preceding the survey; at least as many in each country have assisted grown children in non-monetary ways.

Notably, in all three countries, financial help is more likely to flow down to adult children than up to aging parents. However, when it comes to “sweat equity,” about as many in each country are assisting senior-age parents with their needs as are helping adult children with child care, errands, housework and other day-to-day tasks.

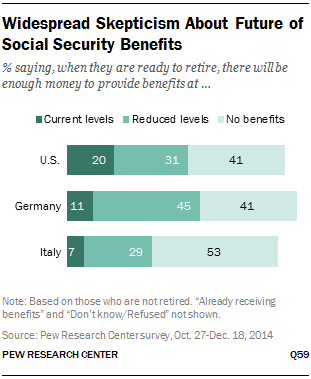

Widespread Concerns About the Future of Social Security

Even as about half or more of Italians and Germans say the state should be mostly responsible for ensuring financial stability in old age, many in all three countries surveyed are skeptical that there will be enough money in their countries’ social security systems when they retire to provide benefits, even at a reduced level. All three systems are financed through worker contributions and, in Europe more than in the U.S., the growing number of older adults along with a shrinking pool of younger active contributors has made it difficult to fund pensions for current retirees.

Among those who have not yet retired, only 20% of Americans expect the Social Security system to have enough money when they are ready to retire to provide them with benefits at current levels. An additional 31% say they expect to receive benefits at reduced levels, and 41% think they will receive no benefits at all.

Among those who have not yet retired, only 20% of Americans expect the Social Security system to have enough money when they are ready to retire to provide them with benefits at current levels. An additional 31% say they expect to receive benefits at reduced levels, and 41% think they will receive no benefits at all.

Germans and Italians are even more doubtful that their countries’ social security systems will be able to maintain their current levels of support. In Germany, 11% think they will receive benefits from the Gesetzliche Rentenversicherung (Germany’s equivalent to the U.S. Social Security system) at current levels, 45% think they will receive benefits at reduced levels, and 41% expect to get no benefits at all. Among Italians, only 7% believe there will be enough money in the Previdenza Sociale to provide them with benefits at their current levels, 29% expect benefits but at reduced levels, and fully 53% think they will not get any benefits.

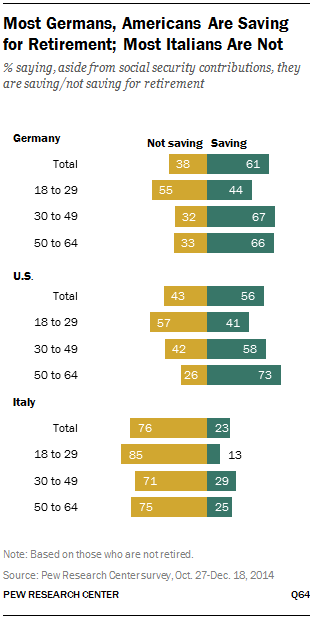

Few Italians Saving for Retirement

If government benefits are reduced or not available, future retirees will need to rely even more heavily on their own personal savings. More than half of Americans (56%) and Germans (61%) who are not retired say they are putting money in a private retirement plan or other savings account aside from social security contributions. But in Italy, just 23% say they are doing this; fully 76% say they are not saving for retirement.

If government benefits are reduced or not available, future retirees will need to rely even more heavily on their own personal savings. More than half of Americans (56%) and Germans (61%) who are not retired say they are putting money in a private retirement plan or other savings account aside from social security contributions. But in Italy, just 23% say they are doing this; fully 76% say they are not saving for retirement.

In all three countries, majorities of young adults ages 18 to 29 say they are not currently saving for retirement aside from social security contributions. Still, a substantial share of young adults in Germany (44%) and the U.S. (41%) say they are saving for retirement. By comparison, only 13% of young adults in Italy say they are saving for retirement. And even among Italians ages 50 to 64 –those who are closest to retiring – only 25% say they are putting money in a private retirement plan or other private savings account.

Men and women are equally likely to say they are saving for retirement, whether in the U.S., Germany or Italy. And across all three countries, saving for retirement is highly correlated with financial security. Those who say they live comfortably are among the most likely to report that they are saving for retirement beyond what they are contributing to social security, while those who say they do not have enough money to meet their basic expenses are among the least likely to be saving.

In fact, most adults who are not saving for retirement report that this is mainly because they do not have enough money to save right now, while relatively few say it is because they have not yet started to think about retirement. About two-thirds of Americans and Italians who are not currently saving for retirement say this is mainly because they lack the funds, as do about half in Germany.

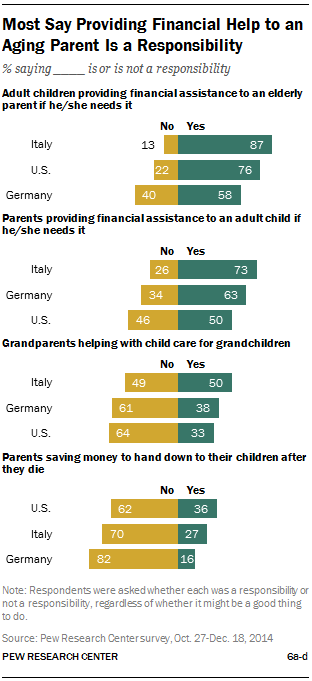

Most See Helping an Aging Parent as a Responsibility

In addition to relying more heavily on private savings, future retirees may also need to turn to family members for support as they age. Majorities across the three countries believe adult children have a responsibility to provide financial assistance to an aging parent in need. Many also see providing financial support for adult children as a responsibility, while far fewer say the same about providing childcare for grandchildren or saving money to hand down to their children after they die.

About three-quarters or more in Italy (87%) and the U.S. (76%) view providing financial assistance to aging parents in need as a responsibility, as do 58% in Germany. Young Americans and Germans are more likely than older people in their countries to say adult children have a responsibility to help aging parents in need; 86% of 18- to 29-year-olds in the U.S. and 76% in Germany see this as a responsibility, compared with 64% of Americans and 57% of Germans ages 65 and older.

About three-quarters or more in Italy (87%) and the U.S. (76%) view providing financial assistance to aging parents in need as a responsibility, as do 58% in Germany. Young Americans and Germans are more likely than older people in their countries to say adult children have a responsibility to help aging parents in need; 86% of 18- to 29-year-olds in the U.S. and 76% in Germany see this as a responsibility, compared with 64% of Americans and 57% of Germans ages 65 and older.

Similar shares of Italians across age groups see helping an aging parent in need as a responsibility but, unlike in the U.S. and Germany, there are differences in how younger and older Italians perceive support to grown children. More than eight-in-ten (85%) Italians ages 65 and older say providing financial support to an adult child in need is a responsibility, compared with 58% of 18- to 29-year-olds. Overall, 73% of Italians and 63% of Germans say parents have a responsibility to help an adult child financially if needed; half of Americans share this view.

When asked about helping with child care for grandchildren, half of Italians see it as a responsibility; about four-in-ten (38%) Germans and one-third of Americans say this is the case. And while Americans are somewhat more likely than Italians and Germans to say parents have a responsibility to leave behind an inheritance, relatively few in each country say so (36%, 27% and 16%, respectively).

More Are Giving Time Rather than Money to Help Aging Parents

Assistance to aging parents and to adult children takes on many forms, but in all three countries, more say they are helping their aging parents with errands, housework or home repairs than say they are providing financial help or help with personal care, such as helping them bathe or get dressed. The pattern of support to adult children is less consistent across countries.1

Assistance to aging parents and to adult children takes on many forms, but in all three countries, more say they are helping their aging parents with errands, housework or home repairs than say they are providing financial help or help with personal care, such as helping them bathe or get dressed. The pattern of support to adult children is less consistent across countries.1

Seven-in-ten Italians (70%) say they have helped an aging parent with errands, housework or home repairs in the 12 months preceding the survey, while about a quarter or fewer say they have provided help with personal care (26%) or finances (20%). Similarly, 68% of Germans with an aging parent have helped with errands, housework or home repairs, but half as many as in Italy have assisted a parent with personal care; 13% in Germany have done this. As in Italy, about one-in-five Germans (18%) have helped an aging parent financially.

In the U.S., about six-in-ten (58%) have assisted an aging parent with errands, housework or home repairs in the preceding 12 months. About three-in-ten (28%) say they have helped financially, while half as many (14%) say they have helped a parent with personal care, such as bathing or getting dressed.

In the three countries surveyed, more say they have given financial help to an adult child in the preceding 12 months than say they have similarly helped an aging parent. About six-in-ten (61%) Americans with at least one grown child say they have given their children at least some financial support, far more than say they have helped their children with errands, housework or home repairs (39%) or with child care (33%).

In Italy and Germany, about as many say they have helped their children financially as say they have helped with errands, housework or home repairs. About six-in-ten Italians with an adult child say they have provided each type of assistance in the preceding 12 months; among Germans, 48% say they have helped a grown child financially and 44% say they have helped with errands, housework or home repairs. About a third of Italians (35%) and Germans (33%) with grown children have helped with child care.

The Sandwich Generation

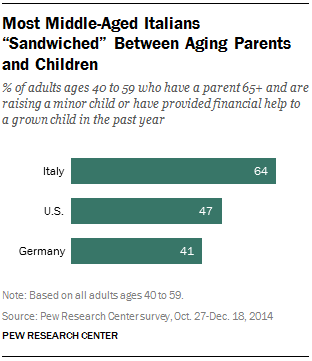

About three-in-ten (31%) adults in Italy, 23% of Americans and 19% of Germans overall are “sandwiched” between their children and their parents – that is, they have one or two parents age 65 or older and are either raising a young child or have provided financial assistance to a grown child in the preceding 12 months. Among those in their 40s and 50s, much larger shares are in this situation.

About three-in-ten (31%) adults in Italy, 23% of Americans and 19% of Germans overall are “sandwiched” between their children and their parents – that is, they have one or two parents age 65 or older and are either raising a young child or have provided financial assistance to a grown child in the preceding 12 months. Among those in their 40s and 50s, much larger shares are in this situation.

Fully 64% Italians in their 40s and 50s have a parent age 65 or older and are either raising a young child or have provided financial assistance to a grown child in the preceding 12 months. Nearly half of Americans (47%) and 41% of Germans in the same age group are also sandwiched between their children and aging parents.

Despite the added demand on this group, many of whom are providing financial and other help to both an aging parent and an adult child, those who are part of the sandwich generation are as likely as other adults to say they are generally happy with their lives and to express high levels of satisfaction with their family life, the number of friends they have, the quality of life in their community and their present housing situation. They are also no more likely than other adults to say helping an aging parent is stressful. In the U.S., however, those who are sandwiched between generations are more likely to say helping an adult child is stressful than those who have provided financial help to an adult child but are not part of the sandwich generation; this is not the case in Germany and Italy.

The remainder of this report looks at demographic shifts in the U.S., Germany and Italy and family support for younger and older generations. Chapter 1 examines the age structures in the three countries and the financial profiles of the younger and older generations. Chapter 2 looks at public attitudes about the type of intergenerational support families have a responsibility to provide. Chapter 3 explores the experiences of American, German and Italian adults ages 65 and older, including what they see as advantages and disadvantages of getting old. Chapters 4 and 5 focus on people’s personal experiences caring for aging parents and helping adult children. And Chapter 6 examines the frequency and modes of communication across generations.

Other Key Findings

In the three countries surveyed, more say that helping an aging parent or an adult child is rewarding than say it is stressful. More than eight-in-ten adults who are providing help to a parent age 65 or older in the U.S. (88%), Italy (88%) and Germany (84%) say that doing so is rewarding, while about a third or less in each country find it stressful. Similarly, among those who are helping their grown children, 91% in Italy, 89% in the U.S. and 86% in Germany say that it is rewarding; 12%, 30% and 15%, respectively, say it is stressful.

Many see upsides to getting older. More than six-in-ten adults ages 65 and older in the U.S., Germany and Italy say they are spending more time with their family and on hobbies as they get older. About half or more also say they are experiencing less stress.

Older adults who are married are more likely than those who are not currently married to say they are very satisfied with their family life. This is the case among adults ages 65 and older in the three countries surveyed, but it is particularly pronounced in Italy and Germany, where older adults who are married are about twice as likely as those who aren’t to say they are very satisfied with their family life (50% vs. 26% in Italy and 70% vs. 35% in Germany).

Nearly half of Italians say an adult child is living with them in their home for most of the year. Among Italians ages 50 to 64, six-in-ten say this is the case. In contrast, 30% of Americans and 27% of Germans in the same age group say an adult child – or possibly more than one – lives with them.

Seven-in-ten Italians say they are in contact at least once a day with their adult children who don’t live with them. Fewer in the U.S. (46%) and Germany (32%) say this is the case. Among those who say they are contact with their children once a month or more frequently, Americans are more likely than Germans and Italians to use text messages, email and Facebook or other social networking sites to stay in touch.

About This Report

This report, produced by the Pew Research Center, aims at understanding intergenerational relations in three countries that are undergoing rapid aging – the United States, Germany and Italy. Parallel surveys were administered in these three countries, the grayest of the West’s advanced economies, to explore the ways in which families are coping or providing support across generations as they experience this major demographic shift. The surveys were conducted among 1,692 adults in the United States, 1,700 in Germany and 1,516 in Italy, from Oct. 27 to Dec. 18, 2014.

Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan “fact tank” that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping America and the world. It does not take policy positions. The center conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, content analysis and other data-driven social science research. It studies U.S. politics and policy; journalism and media; internet, science and technology; religion and public life; Hispanic trends; global attitudes and trends; and U.S. social and demographic trends. All of the center’s reports are available at www.pewresearch.org.

Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts, its primary funder. This report was made possible by The Pew Charitable Trusts, which received support for the survey from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. The study was conducted in conjunction with the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on an Aging Society, which is chaired by John Rowe, M.D., Julius B. Richmond Professor of Health Policy and Aging at the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University.

This report is a collaborative effort based on the input and analysis of several individuals listed below. In addition, Pew Research received invaluable advice on the development of the survey questionnaire from Frank Furstenberg, professor of sociology and research associate in the Population Studies Center at the University of Pennsylvania.

Principal Researchers

Kim Parker, Director of Social Trends Research

Juliana Menasce Horowitz, Associate Director, Research

Research Team

James Bell, Vice President, Global Strategy

Gretchen Livingston, Senior Researcher

Steve Schwarzer, Research Methodologist

Eileen Patten, Research Analyst

Publishing

Michael Suh, Associate Digital Producer

Graphic Design

Michael Keegan, Information Graphics Designer

Interactives

Dana Amihere, Web Developer

Copy editing

Marcia Kramer, Kramer Editing Services