Overview

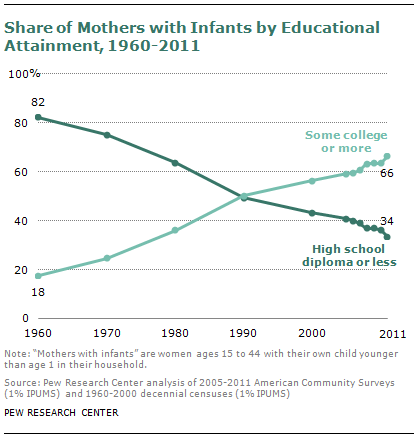

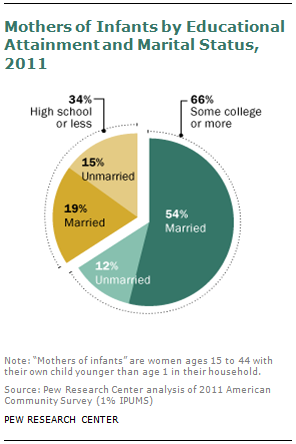

Mothers with infant children1 in the U.S. today are more educated than they ever have been. In 2011, more than six-in-ten (66%) had at least some college education, while 34% had a high school diploma or less and just 14% lacked a high school diploma, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data.

Mothers with infant children1 in the U.S. today are more educated than they ever have been. In 2011, more than six-in-ten (66%) had at least some college education, while 34% had a high school diploma or less and just 14% lacked a high school diploma, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data.

These benchmarks reflect a decades-long rise in the educational levels of all women, as well as a decline in births that has been particularly steep among less educated women, and that has intensified since the onset of the Great Recession in late 2007.2

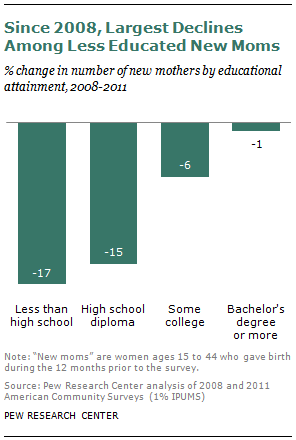

From 2008 to 2011, the number of new mothers with less than a high school diploma declined 17%, and the number with only a high school diploma went down 15%. By contrast, the number of new mothers with some college education fell by 6%, and the number with a bachelor’s degree or more fell by just 1%.

Although less educated women are a shrinking share of all new mothers, less educated women still have a higher average number of births throughout their lifetime than more educated women. By the end of their childbearing years, women without a high school diploma have on average 2.5 children, and women with a bachelor’s degree have about 1.7. This gap has closed only slightly over the past 25 years.

Although less educated women are a shrinking share of all new mothers, less educated women still have a higher average number of births throughout their lifetime than more educated women. By the end of their childbearing years, women without a high school diploma have on average 2.5 children, and women with a bachelor’s degree have about 1.7. This gap has closed only slightly over the past 25 years.

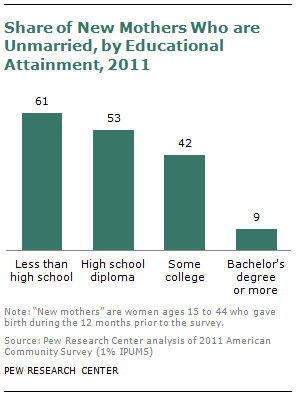

There are significant differences in the marital status of new mothers depending upon their educational attainment. While about six-in-ten (61% in 2011) women with less than a high school diploma are unmarried when they give birth, this share declines to only 9% among women with at least a bachelor’s degree.

The age profile of new mothers varies by their educational attainment as well. While almost half (48%) of new mothers without a high school diploma are younger than 25, only 3% of new mothers with a bachelor’s degree are younger than 25.

Experts have identified a strong linkage between child well-being and maternal education levels. On average, a mother with more education is more likely to deliver a baby at term and more likely to have a baby with a healthy birth weight. As they grow up, children with more educated mothers tend to have better cognitive skills and higher academic achievement than others. It is difficult to determine whether maternal education is causing some of these outcomes, or if it is serving as a proxy for some other causal factor (for example, economic well-being). What is irrefutable, though, is that on average the more education a woman has, the better off her children will be

About the Data

This report is based primarily upon two slightly different indicators of fertility.For analysis of the 2008-2011 period, a “new mother” is defined as a woman between the ages of 15 and 44 who reports having given birth in the past 12 months. American Community Survey data, Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS), are used to derive this variable.

This variable is unavailable for earlier years, so longer-term trend analysis is based upon IPUMS Census data for 1960-2000 and IPUMS American Community Survey data for subsequent years.

In the longer-term trend analysis, a “mother of an infant” is defined as a woman between the ages of 15 and 44 who reports that her youngest child living in her household is younger than age 1. This measure includes a small share of women with adopted or stepchildren and excludes the small share of women who gave birth in the past year but do not live with their children.

Because these two variables are based upon slightly different universes, and different questions, they produce slightly different statistics. Generally, though, they both tell a similar story.

In all analysis, women’s characteristics such as education, marital status and age are based upon responses at the time of survey, not the time of birth.

Terminology

New mother: a woman between the ages of 15 and 44 who has given birth in the past 12 months

Mother of an infant: a woman between the ages of 15 and 44 who reports that she has one of her own children younger than age 1 living in her household

Rising Educational Attainment of New Mothers

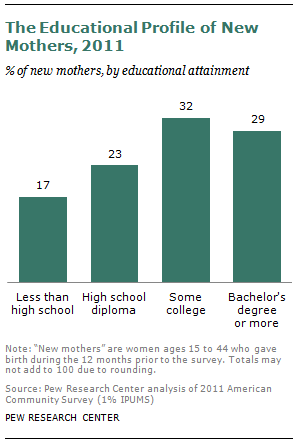

In 2011, fully 83% of new mothers had at least a high school diploma when they gave birth. Only 17% did not finish high school. Almost one-fourth (23%) had a high school diploma. The remaining 61%3 had at least some college experience, including 32% who had attended college but not attained a bachelor’s degree and 29% who had earned at least a bachelor’s degree.

In 2011, fully 83% of new mothers had at least a high school diploma when they gave birth. Only 17% did not finish high school. Almost one-fourth (23%) had a high school diploma. The remaining 61%3 had at least some college experience, including 32% who had attended college but not attained a bachelor’s degree and 29% who had earned at least a bachelor’s degree.

This phenomenon of relatively well-educated new mothers can partially be explained by the recent recession, which has hit the less educated especially hard. From 2008 to 2011, there was a 17% drop in the number of new mothers with less than a high school diploma, and a 15% drop in new mothers with a high school diploma. The number of new mothers with some college education also declined, but by only 6%. The number of new mothers with at least a bachelor’s degree decreased by only 1% in those years.

While the increasingly high educational profile of new mothers has been hastened by the recession, the change also reflects a long-term trend. In 2011, more than six-in-ten mothers of infants had at least some college experience; in 1960 only 18% of mothers with infants fell into this category.4 (Since 1990, the share of mothers with an infant who have some college education increased from 30% to 32%, while the share of mothers with an infant with a bachelor’s degree or more increased from 20% to 35%.) Women with a high school diploma or less made up 34% of mothers with an infant in 2011, but 82% of mothers with an infant in 1960. In 1960, the plurality of mothers with an infant—43%—lacked a high school diploma.

Drivers of Rising Maternal Education

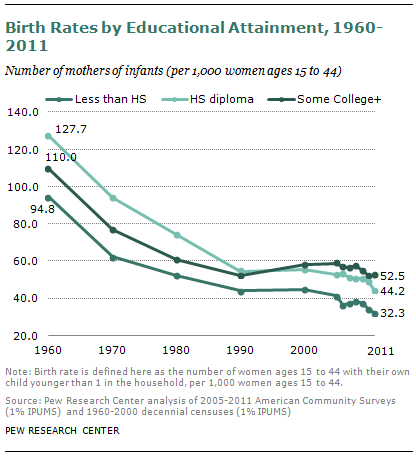

The transformation in the educational profile of mothers of infants is driven largely, but not completely, by the fact that the share of women with at least some college education has more than doubled since 1960. However, differential birth rates also play a role: While rates have declined for all women in recent decades, the declines have been steepest among the least educated.

The transformation in the educational profile of mothers of infants is driven largely, but not completely, by the fact that the share of women with at least some college education has more than doubled since 1960. However, differential birth rates also play a role: While rates have declined for all women in recent decades, the declines have been steepest among the least educated.

Since the Great Recession began, educational attainment of women of childbearing age has risen rapidly. The share of women ages 15 to 44 with less than a high school diploma declined by 5%, and the share with only a high school diploma but no further education declined by 4%. In contrast, the number of women of childbearing age with some college education rose 3% during those years, and the number of women with a college degree jumped 6%.

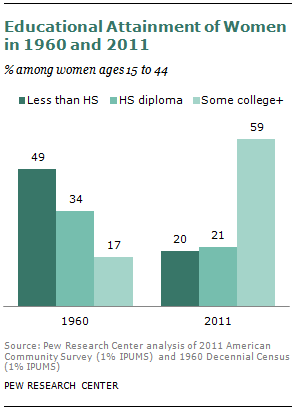

In the longer term too, rising educational attainment among women overall has changed the pool of potential mothers. In 1960, almost half (49%) of women ages 15 to 44 had less than a high school diploma, some 34% had earned a high school diploma, and 17% had at least some college experience. However, by 2011, only one-fifth (20%) of women had less than a high school diploma, a similar share (21%) had a high school diploma, and the rest (59%) had attended college.

The educational profile of mothers with infants generally tracks the share of women in each educational grouping, although less educated women are somewhat underrepresented among new mothers and women with college experience are somewhat overrepresented. In 2011, 20% of women ages 15 to 44 had less than a high school diploma, but this group accounted for 14% of mothers of infants; 21% of women had a high school diploma, and this group accounted for 20% of mothers of infants; and 59% of women had college experience (or a degree), and this group accounted for 66% of mothers of infants.

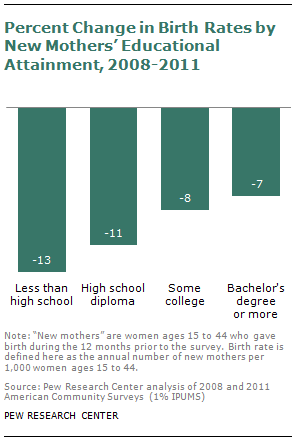

Changing birth rates, too, have played a part in both the recent and longer-term rise in educational attainment of new mothers. The recent marked declines in births, particularly for less educated women, have been driven in part by rate declines during the recession.

Changing birth rates, too, have played a part in both the recent and longer-term rise in educational attainment of new mothers. The recent marked declines in births, particularly for less educated women, have been driven in part by rate declines during the recession.

From 2008 to 2011, birth rates5 declined 13% for women lacking a high school diploma, and 11% for women with a high school diploma. Birth rates declined for women with at least some exposure to college, but somewhat more moderately. From 2008 to 2011, there was an 8% drop in rates for women with some college education, and a 7% decline for women with a bachelor’s degree or more.

These findings are consistent with past analyses conducted by the Pew Research Center that suggest the recent recession contributed to overall declines in fertility. The associations are particularly notable for blacks, Hispanics, young adults and lower income adults—all groups with lower than average educational attainment. For instance, a Pew Research Center survey revealed that, among childbearing-age respondents, younger adults and lower income adults were far more likely than others to say they delayed childbearing as a result of the recession.6

It is also the case that blacks and Hispanics have fared worse than whites, according to many economic indicators. These same groups experienced relatively large fertility declines during the 2008-2011 period, compared with whites.

U.S. birth rates were declining even before the recession began, affecting the less educated more than college-educated women. For women ages 15 to 44 with less than a high school diploma, annual birth rates7 declined 66% from 1960 to 2011. The decline was similar (65%) for women with a high school diploma.8 Rates dropped among women with at least some college education, but not as steeply (52%, from 110 births per 1,000 women in 1960 to 53 births per 1,000 women in 2011).

Another measure of fertility—childlessness—shows similar trends. Among women approaching the end of their childbearing years, the more educated are still more likely to be childless than others, but it is among the least educated that childlessness has increased over the last two decades.

Another measure of fertility—childlessness—shows similar trends. Among women approaching the end of their childbearing years, the more educated are still more likely to be childless than others, but it is among the least educated that childlessness has increased over the last two decades.

College-educated women are less likely to be childless now than in the past. In the early 1990s, about 10% of women ages 40 to 44 with less than a high school diploma had no biological children, and by 2010 that share had increased to 13%. Conversely, in the early 1990s, some 26% of women ages 40 to 44 with a bachelor’s degree or more had no biological children, and by 2010 this share had declined to 22%.

Lifetime Fertility by Educational Attainment

While less educated women account for a small and shrinking share of all new births in the U.S., they still have a higher average number of biological children over their lifetime than their better educated counterparts. This pattern has remained relatively stable for decades.

In 1960, women ages 45 to 50 with less than a high school diploma had an estimated 2.5 biological children in their lifetime. Women with a high school diploma or some college had an average 1.8 biological children, and women with a bachelor’s degree had an average 1.5 biological children (Isen and Stevenson, 2010).

In 1960, women ages 45 to 50 with less than a high school diploma had an estimated 2.5 biological children in their lifetime. Women with a high school diploma or some college had an average 1.8 biological children, and women with a bachelor’s degree had an average 1.5 biological children (Isen and Stevenson, 2010).

Estimates using the Current Population Survey (CPS) suggest that the educational gap in cumulative fertility may have shrunk slightly, but remains in place. In 20109, women ages 40 to 44 with less than a high school diploma had borne an average of 2.5 children in their lifetime. Women with a high school diploma or some college had about 1.9 children, and women with at least a bachelor’s degree had 1.7 biological children.

Given that fertility rates in recent years have fallen more for the less educated than for the better educated, it may be the case that lifetime fertility will converge across educational characteristics in coming decades. However, it’s difficult to predict as much, particularly since many experts suspect that people who have postponed childbearing during the recession may eventually “catch up” on the fertility that they had delayed.10

Education and Marital Status

Women with a bachelor’s degree are far less likely to be unmarried at the time they give birth than are less educated women. While just 9% of women with a bachelor’s degree are unmarried, the share among women with some college is more than four times higher—42%. Just over half (53%) of women with a high school diploma are unmarried when they give birth, as are 61% of women lacking a high school diploma.11

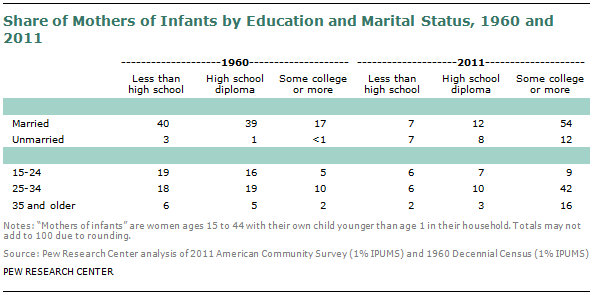

Among all women with infants in 2011, by far the largest share were married with at least some college education (54%); this compares with only 17% in 1960.

Among all women with infants in 2011, by far the largest share were married with at least some college education (54%); this compares with only 17% in 1960.

Among the remaining women with infants in 2011, 19% were married with a high school diploma or less; 15% were unmarried with a high school diploma or less; and 12% were unmarried with at least some college experience. In 1960, the largest share of women with infants (79%) were married with no college experience—of those, about half (52%) had no high school diploma.

The current pattern of fertility and marital status is largely due to the close link between marriage and educational attainment. Women with college experience are more likely to be married than their less educated counterparts.

Among women of childbearing age, 20% of those without a high school diploma are married, compared with 37% of high school graduates and 36% of women with some college experience. More than half (56%) of women ages 15 to 44 with a bachelor’s degree are married.

Among women of childbearing age, 20% of those without a high school diploma are married, compared with 37% of high school graduates and 36% of women with some college experience. More than half (56%) of women ages 15 to 44 with a bachelor’s degree are married.

Moreover, while marital birth rates are higher than non-marital birth rates for women of all educational levels, the link between marriage and childbearing is particularly strong for more educated women, especially those with a bachelor’s degree. Among more educated women, birth rates are far higher for those who are married than for those who are not. Among the less educated, there is a much smaller gap between birth rates for married and unmarried women.

For example, among those with a college degree, the annual birth rate in 2011 for married women was much higher (118 births per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44) than the birth rate for unmarried women (16 births per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44).

By contrast, among high school educated women, the 2011 annual birth rate was 86 births per 1,000 married women ages 15 to 44, compared with 59 births per 1,000 unmarried women ages 15 to 44.12

Education and Age

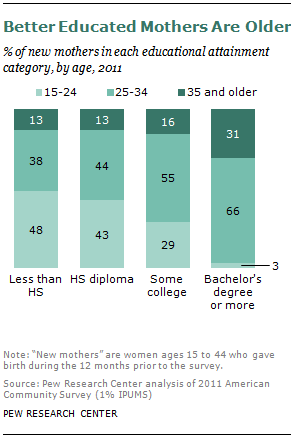

On average, the more education a woman obtains, the older she is when she gives birth. According to 2011 data, almost half (48%) of women with less than a high school diploma who gave birth in the prior year were younger than 25; for high school graduates, this number is 43%. Among women with some college, just 29% who gave birth in the prior year were younger than 25, and for women with a bachelor’s degree, this share is only 3%. At the other end of the age spectrum, new mothers with a bachelor’s degree are about twice as likely as all other new mothers to be ages 35 or older—31% are, compared with 13% of women with a high school diploma or less, and 16% of women with some college.

On average, the more education a woman obtains, the older she is when she gives birth. According to 2011 data, almost half (48%) of women with less than a high school diploma who gave birth in the prior year were younger than 25; for high school graduates, this number is 43%. Among women with some college, just 29% who gave birth in the prior year were younger than 25, and for women with a bachelor’s degree, this share is only 3%. At the other end of the age spectrum, new mothers with a bachelor’s degree are about twice as likely as all other new mothers to be ages 35 or older—31% are, compared with 13% of women with a high school diploma or less, and 16% of women with some college.

The fertility plunge among less educated women from 2008 to 2011, as compared with more educated women, is associated with the aging of new mothers in that time period. Since 2008, birth rates have risen only for older women (up 9% for those ages 40 to 44). Conversely, the largest declines in birth rates have been among the youngest women, who also tend to be the least educated. Among teens, birth rates declined 19% from 2008 to 2011; among women in their early 20s, rates fell 17% over the same period. Women in their late 20s have also experienced a marked fertility decline, with the rate dropping 14% from 2008 to 2011. Rates declined less dramatically for women in their 30s—5% for women in their early 30s, and 2% for women in their late 30s.

This short-term trend may be due to the fact that younger, less educated women have been particularly hard hit by the recession, and thus have delayed childbearing. Or, it may be the case that younger women know that they have the time to “make-up” childbearing when their prospects improve in the future, while the typical 40-year-old does not have that opportunity.

Looking at the longer horizon further illustrates that as larger shares of women have opted for higher education, they have delayed childbearing, resulting in an aging population of mothers with infants. For instance, when age and educational attainment are analyzed together, the largest category of mothers of infants in 2011—accounting for 42%—includes those ages 25 to 34 with at least some college education. By comparison, only 10% of mothers of infants in 1960 fell into this category.