I. Overview

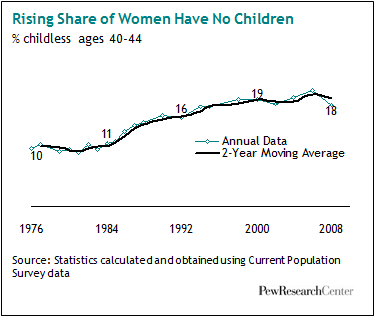

Nearly one-in-five American women ends her childbearing years without having borne a child, compared with one-in-ten in the 1970s. While childlessness has risen for all racial and ethnic groups, and most education levels, it has fallen over the past decade for women with advanced degrees.

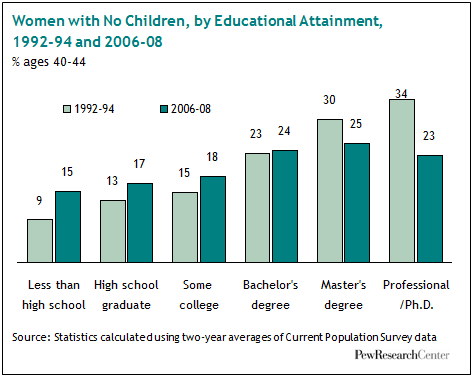

The most educated women still are among the most likely never to have had a child. But in a notable exception to the overall rising trend, in 2008, 24% of women ages 40-44 with a master’s, doctoral or professional degree had not had children, a decline from 31% in 1994.

The most educated women still are among the most likely never to have had a child. But in a notable exception to the overall rising trend, in 2008, 24% of women ages 40-44 with a master’s, doctoral or professional degree had not had children, a decline from 31% in 1994.

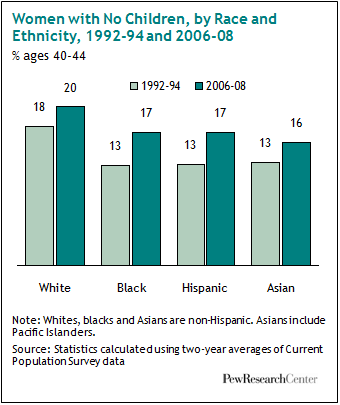

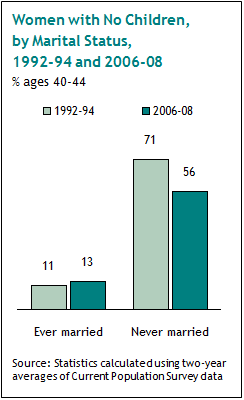

By race and ethnic group, white women are most likely not to have borne a child. But over the past decade, childless rates have risen more rapidly for black, Hispanic and Asian women, so the racial gap has narrowed. By marital status, women who have never married are most likely to be childless, but their rates have declined over the past decade, while the rate of childlessness has risen for the so-called ever-married — those who are married or were at one time.

Among all women ages 40-44, the proportion that has never given birth, 18% in 2008, has grown by 80% since 1976, when it was 10%. There were 1.9 million childless women ages 40-44 in 2008, compared with nearly 580,000 in 1976.

This report is based mainly on data from the June fertility supplement of the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey. The main comparisons use combined data from 2006 and 2008 (referred to in the report as “2008”) and from 1992 and 1994 (referred to as “1994”). Two years of data are combined for each time point so as to have adequate sample size for detailed analysis. This report uses the standard measure of childlessness at the end of childbearing years, which is the share of women ages 40-44 who have not borne any children.1

Attitudes and International Comparisons

Over the past few decades, public attitudes toward childlessness have become more accepting. Most adults disagree that people without children “lead empty lives,” a share that rose to 59% in 2002 from 39% in 1988, according to the General Social Survey. In addition, children increasingly are seen as less central to a good marriage. In a 2007 Pew Research Center survey, 41% of adults said that children are very important for a successful marriage, a decline from 65% who said so in 1990.

As for the impact on society, attitudes are more mixed. About half the public — 46% in a 2009 Pew Research Center poll — say it makes no difference one way or the other that a growing share of women do not ever have children. Still, a notable share of Americans — 38% in that 2009 survey — say this trend is bad for society, an increase from 29% in a 2007 Pew Research survey.

Compared with other developed nations, childless rates in the United States are on par with some nations and higher than others, according to data compiled by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Among women born in 1960, 17% in the U.S. were childless at approximately age 40, compared with 22% in the United Kingdom, 19% in Finland and the Netherlands, and 17% in Italy and Ireland. Rates ranged from 12% to 14% for Spain, Norway, Denmark, Belgium and Sweden, and from 7% to 11% for several Eastern European countries and Iceland.

Possible Explanations

Why has childlessness risen in recent decades? Scholars say that social pressure to bear children appears to have diminished for women and that today the decision to have a child is seen as an individual choice.2 Improved job opportunities and contraceptive methods help create alternatives for women who choose not to have children.

At the same time, there has been a general trend toward delayed marriage and childbearing, especially among highly educated women. Given that the chance of a successful pregnancy declines with age, some women who hope to have children never will, despite the rise in fertility treatments that facilitate pregnancy.

About 10% of women ages 15-44 are not able to get pregnant after a year of trying (six months if ages 35 and older), according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Among older women, ages 40-44, there are equal numbers of women who are childless by choice and those who would like children but cannot have them, according to an analysis of data from the National Survey of Family Growth.3 In 2002, among women ages 40-44, 6% were deemed voluntarily childless, 6% involuntarily childless and 2% childless but hoping to have children in the future.

Some women who do not bear their own children raise children as adoptive mothers or stepmothers. According to the 2008 American Community Survey, there are 61.6 million biological children in U.S. households, as well as 1.6 million adopted children and 2.5 million stepchildren. This report analyzes only the population of women who have not borne biological children.

Differences by Education

Childlessness is most common among highly educated women. In 2008, 24% of women ages 40-44 with a bachelor’s degree had not had a child. Rates were similar for women with a master’s degree (25%) and those with a doctorate or a professional degree, such as a medical or legal degree (23%).

Childlessness is most common among highly educated women. In 2008, 24% of women ages 40-44 with a bachelor’s degree had not had a child. Rates were similar for women with a master’s degree (25%) and those with a doctorate or a professional degree, such as a medical or legal degree (23%).

Among women with some college but no degree, 18% were childless in 2008, compared with 17% for high school graduates and 15% of women without a high school diploma.

Since the 1990s, rates of childlessness have risen most sharply for the least educated women. The most dramatic change has occurred among women with less than a high school diploma, whose likelihood of bearing no children rose 66% from 1994 to 2008. Rates rose less steeply over the same time period among high school graduates and women with some college but not a degree.

Among women ages 40-44 with a bachelor’s degree, there has been essentially no change in the likelihood of being childless. But rates have declined among women with advanced degrees — by 17% for those with master’s degrees and 32% for those with doctorates or professional degrees. Women with advanced degrees were more likely in 1994 to be childless than were women with bachelor’s degrees — 34% of women with doctorates or professional degrees were childless, as were 30% of those with master’s degrees and 23% of those with bachelor’s degrees. The decline in childlessness for the most educated women from 1994 to 2008 erased that gap.

Among all women ages 40-44, 9% held an advanced degree (a master’s degree or higher) in 2008.

Differences by Race and Ethnicity

One-in-five (20%) white women ages 40-44 was childless in 2008, the highest rate among racial and ethnic groups.

By comparison, 17% of black and Hispanic women were childless in 2008, and 16% of Asian women were childless.

Rates of childlessness rose more for nonwhites than whites from 1994 to 2008.

During those years, the childlessness rates for black women and for Hispanic women grew by more than 30%. The rate for white women increased only 11%.

Marital Status

Among 40-44-year-old women currently married or married at some point in the past, 13% had no children of their own in 2008, a small increase from 11% in 1994.

Among 40-44-year-old women currently married or married at some point in the past, 13% had no children of their own in 2008, a small increase from 11% in 1994.

The childless rate among these women rose for whites, blacks and Hispanics, with the largest increases among black and Hispanic women.

A rising share of births is to women who never married, and this is reflected in a decline in childlessness among this group.

Among women in this group, 56% were childless in 2008, compared with 71% in 1994. The childless rate fell for never-married white and black women.4 Data are incomplete for Hispanic and Asian women.

Education, Race, Ethnicity and Marital Status

Looking at race, ethnicity and educational attainment, patterns for whites and Hispanics generally reflect the overall progression of higher childlessness at each higher education level. For blacks and Asians, however, patterns are more mixed.

Among whites ages 40-44 in 2008, childless rates increase at each higher level of education. The share of white women without a child is 27% for those with advanced degrees and 25% for those with bachelor’s degrees, which are similar rates. Among Hispanic women, each higher level of education is accompanied by a higher level of childlessness; 24% of college graduates had not had a child, compared with 13% of women without a high school diploma.

Among comparably aged black women, there is relatively little variation in 2008 rates of childlessness across educational levels. The lowest rate was for women with a high school diploma (16%), and the highest rate was for women with a bachelor’s degree (20%).5 Among Asian women, the lowest levels of childlessness are found among college graduates (13%).

An analysis of marital status and educational attainment finds a general increase in childlessness for both married and unmarried women as education levels rise. In 2008, there is wider variation in childlessness among the never-married. Childlessness among the never-married ranges from 40% (for those with less than a high school diploma) to 85% (for those with an advanced degree). Among the ever-married, childlessness ranges from 9% (for women with less than a high school diploma) to 16% (for those with an advanced degree).

In addition, there are differences in trends over time. From 1994 to 2008, childlessness grew sharply among 40-44-year-old married women with less than a high school education or a high school diploma. The rate grew somewhat for married women with some college education and barely changed for married women with a college degree. The rate of childlessness fell by a fifth among married women with advanced degrees.

Among 40-44-year-old unmarried women, childlessness increased for those without a high school diploma. It declined for all other levels of educational attainment, falling most for women with a high school diploma but no further education.

From 1994 to 2008, the childlessness rate for never-married women with advanced degrees declined by less (11%) than did the childlessness rate for ever-married women with advanced degrees (20%). The rate remains quite high for never-married women with advanced degrees, 85% of whom have not borne children, compared with 16% of ever-married women with advanced degrees.

Comparing Women With and Without Children

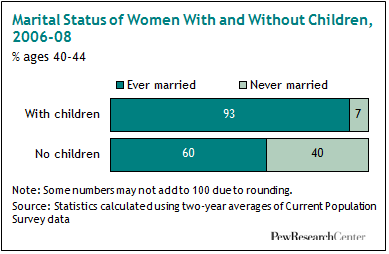

There are dramatic differences by marital status between women ages 40-44 who have borne children and those who have not, and some differences by race and educational attainment.

There are dramatic differences by marital status between women ages 40-44 who have borne children and those who have not, and some differences by race and educational attainment.

Among childless women in 2008, 60% were currently married or had been at some point; among women who had borne children, 93% had ever been married. That means that 40% of childless women have never been married, compared with only 7% of women who had borne children.

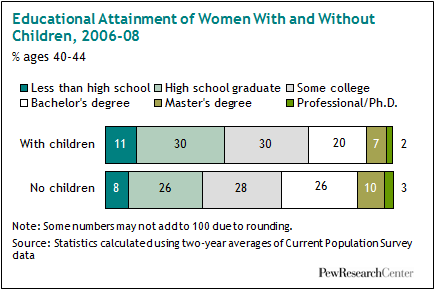

Childless women tend to be somewhat more educated than women who have borne children. Childless women are more likely to hold an advanced degree (13% vs. 9%) and a college degree (26% vs. 20%). Women with at least one child are about as likely to have some college education (30%) as childless women (28%).

Childless women tend to be somewhat more educated than women who have borne children. Childless women are more likely to hold an advanced degree (13% vs. 9%) and a college degree (26% vs. 20%). Women with at least one child are about as likely to have some college education (30%) as childless women (28%).

Women who have borne children are more likely to be high school graduates (30%) than childless women (26%). Women with at least one child also are more likely than childless women not to have completed high school (11% vs. 8%).

More than seven-in-ten (71%) childless women aged 40-44 are white, a slightly higher share than the 66% of women who have borne children who are white. Childless women are less likely to be Hispanic or Asian than their counterparts who have borne children.

More than seven-in-ten (71%) childless women aged 40-44 are white, a slightly higher share than the 66% of women who have borne children who are white. Childless women are less likely to be Hispanic or Asian than their counterparts who have borne children.

Blacks represent 14% of women with children and 12% of childless women. Hispanics are 14% of women who have borne children and 12% of childless women. Asians are 6% of women who have borne children and 5% of childless women.