Whether student debt is growing increasingly burdensome for household finances involves not only the size of the outstanding loan balances but also changes in the household’s other debts and its ability to pay those debts. This section evaluates mounting student debt in the context of two conventional measures of the household’s ability to pay: its household income and its stock of assets. The next section presents evidence on the more well-known relationship of student debt to other types of household debt.

Whether student debt is growing increasingly burdensome for household finances involves not only the size of the outstanding loan balances but also changes in the household’s other debts and its ability to pay those debts. This section evaluates mounting student debt in the context of two conventional measures of the household’s ability to pay: its household income and its stock of assets. The next section presents evidence on the more well-known relationship of student debt to other types of household debt.

Outstanding Student Debt to Income

Mounting student debt would be of less concern if household incomes were rising, but as measured by the SCF, annual household incomes have been falling since 2007 and the decline in household income has not been the same across richer and poorer households.

Mounting student debt would be of less concern if household incomes were rising, but as measured by the SCF, annual household incomes have been falling since 2007 and the decline in household income has not been the same across richer and poorer households.

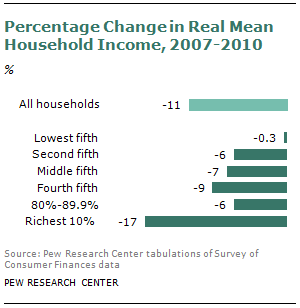

Among all households, mean annual household income fell from $91,275 in 2007 to $80,805 in 2010, or by 11%.

The fifth of households with the lowest incomes did not experience as much of a decline in mean household income as more affluent households. In 2010 the average annual household income of the least affluent one-fifth of households was $13,303, only slightly lower than its 2007 mean household income level of $13,343.

The fifth of households with the lowest incomes did not experience as much of a decline in mean household income as more affluent households. In 2010 the average annual household income of the least affluent one-fifth of households was $13,303, only slightly lower than its 2007 mean household income level of $13,343.

From 2007 to 2010, the mean income of the richest 10% of households declined 17%, from $429,965 to $358,731.

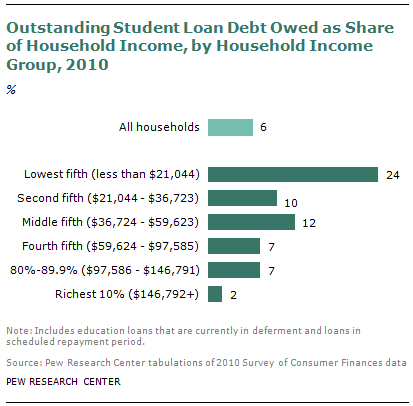

Comparing the stock of outstanding student debt to household income, in 2010 the outstanding debt was 6% of household income. Another way of putting that is that households had 6 cents of outstanding student debt for every dollar of income received.

Comparing the stock of outstanding student debt to household income, in 2010 the outstanding debt was 6% of household income. Another way of putting that is that households had 6 cents of outstanding student debt for every dollar of income received.

Though the least affluent one-fifth of households owe only 13% of the outstanding student debt in 2010, they also have low household incomes. As a result, the student-debt-to-household-income ratio for the least well-off one-fifth of households was 24% in 2010, or their outstanding educational debt amounts to 24 cents for every dollar of their household income.

Alternatively, households in the ninth decile of the household income distribution (those with an annual income between $97,586 and $146,791) or perhaps “upper middle income” owe 17% of the outstanding student debt in 2010. But their household incomes are much larger, and as a result their 2010 student-debt-to-income ratio was 7%, or outstanding student loan balances represented only 7 cents on every dollar of household income.

Alternatively, households in the ninth decile of the household income distribution (those with an annual income between $97,586 and $146,791) or perhaps “upper middle income” owe 17% of the outstanding student debt in 2010. But their household incomes are much larger, and as a result their 2010 student-debt-to-income ratio was 7%, or outstanding student loan balances represented only 7 cents on every dollar of household income.

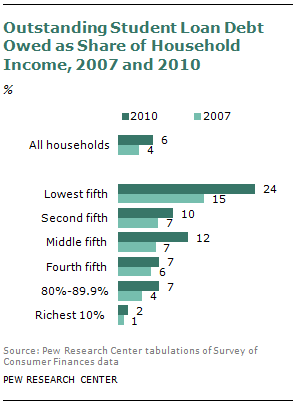

Regarding trend, with outstanding student debt rising and household incomes falling from 2007 to 2010, the student-debt-to-income ratio markedly rose from 2007 to 2010. Across all households, outstanding student debt went from 4 cents on a dollar of income in 2007 to 6 cents in 2010.

For the richest one-fifth of households, the ratio of student debt to income grew significantly. For the richest 10% of households, it doubled from 1 cent on the dollar in 2007 to 2 cents on the dollar in 2010. For households in the ninth decile, the ratio of student debt to income nearly doubled from 4 cents on the dollar in 2007 to 7 cents in 2010.

In comparison, the ratio of student debt to income for the fifth of households with the lowest income increased from 15 cents on the dollar in 2007 to 24 cents in 2010. Although their household income did not decline from 2007 to 2010, these households owe a lot more student debt in 2010 than 2007 (13% of the student debt pie in 2010, up from 11% in 2007).

Outstanding Student Debt to Assets

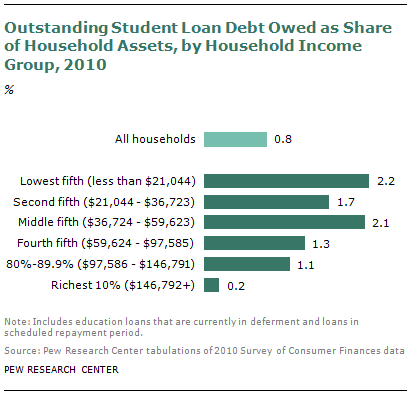

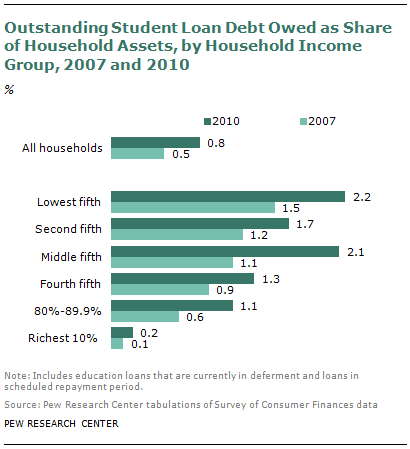

Patterns and trends in the ratio of outstanding student debt to household assets tell a similar story as the debt-to-income ratio. In the SCF, household assets include the value of physical property (equity in properties, equity in automobiles and furnishings and collectibles), financial assets (stocks, bonds and retirement accounts) and equity in businesses. At least in principle, assets can be liquidated to pay off debts and thus debt-to-asset ratios serve as an alternative measure of a household’s ability to handle debt.

Patterns and trends in the ratio of outstanding student debt to household assets tell a similar story as the debt-to-income ratio. In the SCF, household assets include the value of physical property (equity in properties, equity in automobiles and furnishings and collectibles), financial assets (stocks, bonds and retirement accounts) and equity in businesses. At least in principle, assets can be liquidated to pay off debts and thus debt-to-asset ratios serve as an alternative measure of a household’s ability to handle debt.

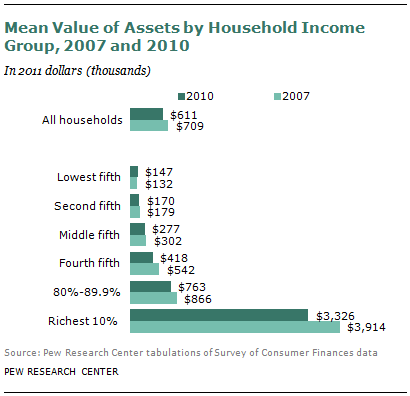

Driven by the housing bust, the value of household assets sharply declined from 2007 to 2010. The mean value of assets among all households fell from $709,000 in 2007 to $611,000 in 2010.

The decline in the value of assets was not uniform across households. Mean assets for households in the lowest fifth of households by income actually increased from $132,000 in 2007 to $147,000 in 2010. Mean assets for households with higher incomes declined from 2007 to 2010.

Households in the lowest fifth of households by income have much less outstanding student debt than do households in the highest fifth. Households in the bottom fifth owe only 13% of the student debt in 2010, while the upper fifth owes 31% of the debt. But the assets of the bottom fifth of households pale in comparison to the assets of the richest fifth of households. The ratio of student debt to assets of the bottom fifth of households (2.2%) is at least twice the size of the ratio of the richest fifth of households. The outstanding student-debt-to-asset ratio

Households in the lowest fifth of households by income have much less outstanding student debt than do households in the highest fifth. Households in the bottom fifth owe only 13% of the student debt in 2010, while the upper fifth owes 31% of the debt. But the assets of the bottom fifth of households pale in comparison to the assets of the richest fifth of households. The ratio of student debt to assets of the bottom fifth of households (2.2%) is at least twice the size of the ratio of the richest fifth of households. The outstanding student-debt-to-asset ratio

for households in the ninth decile of household income was 1.1% in 2010, and the ratio for the richest tenth of households was only 0.2%.

Outstanding student-debt-to-asset ratios roughly doubled for the fifth of households with the highest income from 2007 to 2010, but even so, they remained significantly lower in 2010 than the ratio for households with less income.