Prospects for raising the federal minimum wage, which has stood at $7.25 an hour since 2009, appear to have stalled out yet again, despite broad public support for the idea. In truth, though, for the past several years most of the real action on minimum wages has been in states, counties and cities, not on Capitol Hill. Just this past November, for example, Florida voters approved Amendment 2, which will gradually raise the state’s minimum until it reaches $15 in 2026.

Federal law sets a baseline minimum wage of $7.25 an hour for most U.S. workers, but states are free to adopt their own, higher minimums (and in some states, so are cities and counties). With the push to raise the federal minimum wage once again blocked, we wanted to update our previous look at state and local minimum-wage laws.

Information about minimum-wage rates and rules in each state came primarily from the National Conference of State Legislatures, supplemented by the websites of state labor departments and online versions of each state’s statutes. We compiled a list of cities and counties with local minimum wage ordinances from the University of California at Berkeley’s Center for Labor Research and Education and the Economic Policy Institute, and then verified them through city and county websites and online versions of their laws.

Data on wage and salary employment in states came from the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics; county figures, when needed, came from the BLS’s Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages. State-level data are 2020 annual averages; county-level data are as of the third quarter of 2020, the latest available.

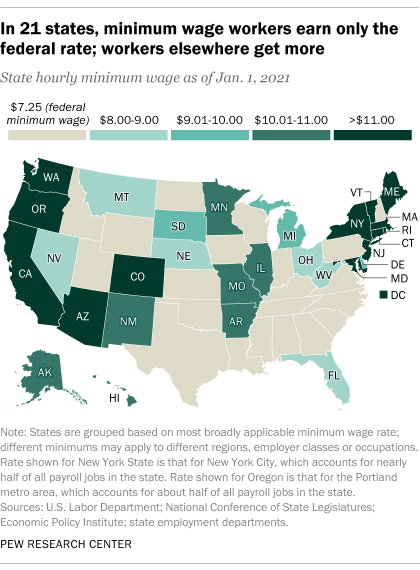

As a practical matter, the $7.25 federal minimum wage is actually used in just 21 states, which collectively account for about 40% of all U.S. wage and salary workers – roughly 56.5 million people – according to our analysis of state minimum-wage laws and federal employment data. In the 29 other states and the District of Columbia, minimum wages are higher – ranging from $8.65 in Florida to $15 in D.C.

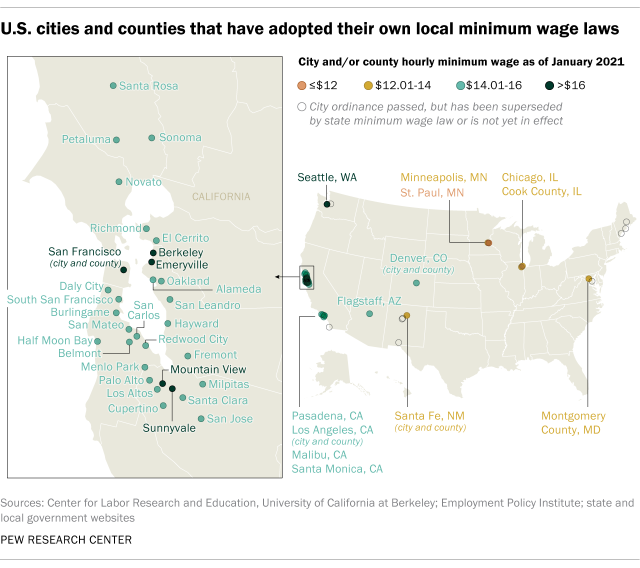

In eight of the states with higher-than-federal minimum wages, some cities and counties have adopted local ordinances that provide for even higher rates than their state’s minimum, accelerate schedules for future increases, or both. (None of the states where the $7.25 federal minimum prevails have higher local minimums.) Our research found at least 46 such cities and counties – most of them (36) in the Los Angeles and San Francisco Bay areas of California. The highest local minimum wage in the country, $16.84, is in Emeryville, a suburb of San Francisco.

A few other cities, such as San Diego and Albuquerque, New Mexico, also have local minimum wage laws, but they’ve been overtaken by increases in state rates. Tacoma, Washington, repealed its local minimum-wage ordinance in 2019 for that reason.

Two states, Oregon and New York, don’t permit localities to adopt their own minimums but have regional variations built into their statewide laws to account for wide cost-of-living differentials within those states. In Oregon, which has a three-tiered wage scale, the “standard” hourly minimum of $12 applies, by our estimate, to only about 38% of the state’s 1.8 million wage and salary workers. The minimum wage is $13.25 for workers in the Portland metro area, the state’s largest (with about half of all wage and salary workers) and most expensive. And in 18 “nonurban” counties, which combined have about 11% of Oregon’s payroll workers, the minimum is $11.50. Scheduled future increases in the three zones (metro Portland, standard counties and nonurban counties) also vary based on the relative cost of living.

Similarly, New York state has one minimum wage for New York City ($15), one for the city’s suburban counties ($14, rising to $15 on Dec. 31), and one for the rest of the state ($12.50, adjusting annually for inflation until it too reaches $15).

The $7.25 federal minimum wage is pretty much one-size-fits-all across industries and occupations (or most: tipped employees, students, farmworkers and young trainees can be paid less under certain circumstances). But states, cities and counties can, and often do, provide for a range of minimums for different types of employers.

Nevada, for instance, sets a minimum wage of $8 an hour for employers that offer their workers health benefits but mandates $9 for employers that don’t. Seattle’s minimum wage is now $16.69 for most employers, but small employers (those with 500 or fewer employees worldwide) can pay $15 if an employee’s tips or company-provided medical benefits equal at least $1.69 an hour.

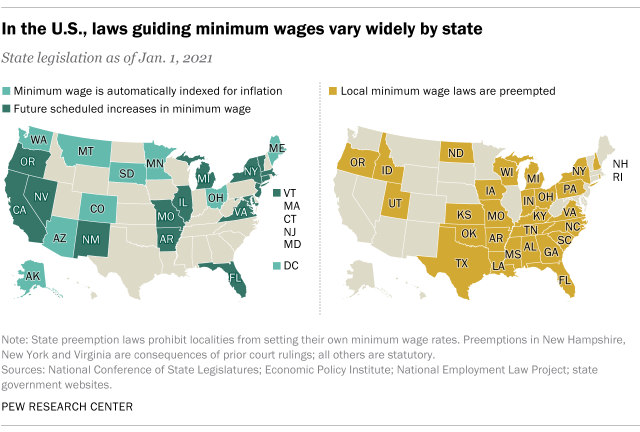

Most states with higher-than-federal minimums also have acted to automate the process of adjusting the minimum wage, rather than leaving it to year-by-year legislative whim. In 10 states (plus D.C.), the minimum wage rises annually based on some sort of inflation or cost-of-living index, with the intent of preserving its current purchasing power. Thirteen other states are in the process of raising their minimums on a multiyear schedule – seven will begin automatic indexing at some point in the future, while in the other six the increases will stop upon reaching a set level. All but one of the 46 cities and counties we identified with their own minimum wages also have adopted automatic cost-of-living increases, either in effect now or beginning at some point in the future.

On the other hand, all but one of the 21 states where the federal minimum wage applies also bar their cities and counties from adopting any higher local minimums (Wyoming being the lone exception). Eighteen of those states have specifically preempted local minimum wage laws through state statutes; in two others, New Hampshire and Virginia, the practice is that local governments can only do those things that state law allows them to do, which so far has not included enacting local minimum wages.

Seven states that have adopted minimum wages beyond the federal standard also have laws that prevent cities and counties from setting their own local minimums. In addition, while New York state doesn’t explicitly preempt local minimum wages, court rulings dating back to the 1960s have held that the state’s minimum-wage law implicitly does so.

Many of the local preemption statutes are relatively recent. Sixteen of the 25 states with such laws adopted them within the past decade – 11 states where the federal minimum wage applies and five states with higher minimums.