The movement for a $15-an-hour minimum wage got a boost earlier this month when Amazon – which has drawn criticism for its pay practices and working conditions – announced it would raise its base pay for all U.S. workers to $15 an hour. The new minimum wage takes effect Nov. 1 and will affect some 250,000 full- and part-time employees, as well as the 100,000 or so seasonal workers Amazon expects to hire in the next few months, according to the company. (The raises will be offset, at least in part, by the phasing out of bonuses and stock awards for hourly workers.)

The movement for a $15-an-hour minimum wage got a boost earlier this month when Amazon – which has drawn criticism for its pay practices and working conditions – announced it would raise its base pay for all U.S. workers to $15 an hour. The new minimum wage takes effect Nov. 1 and will affect some 250,000 full- and part-time employees, as well as the 100,000 or so seasonal workers Amazon expects to hire in the next few months, according to the company. (The raises will be offset, at least in part, by the phasing out of bonuses and stock awards for hourly workers.)

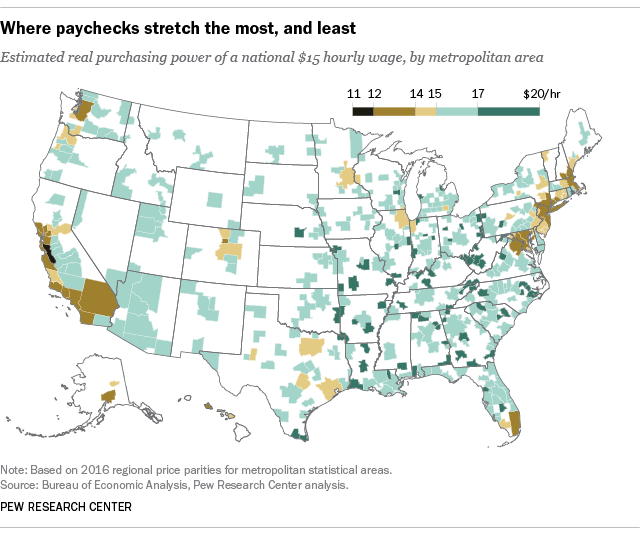

How much of a real improvement those workers will see in their daily lives, however, depends very much on where they live. Local living costs vary widely in the United States, and Amazon has more than 150 warehouses, sorting centers, distribution centers and other facilities scattered across the country. A $15 hourly wage yields $17.10 worth of purchasing power for a worker at Amazon’s Spartanburg, South Carolina, warehouse, for example, but only $13.57 for a worker at the warehouse in Kent, Washington, a Seattle suburb about 20 miles south of the company’s headquarters.

These estimates are calculated by using data on “regional price parities,” or RPPs, for the nation’s 382 metropolitan statistical areas. The RPPs, developed by the federal Bureau of Economic Analysis, measure the difference in local price levels of goods and services across the country, relative to the overall national price level (set at 100). So, on average, prices in the Seattle metro area (RPP of 110.5) are 10.5% higher than the nationwide average, while prices in Spartanburg (RPP of 87.7) are 12.3% below average.

In general, price levels are highest in urban areas and on the coasts – not coincidentally, areas where the push for a $15 minimum wage has been particularly strong. The three most expensive metropolitan areas in the country are all in and around the San Francisco Bay Area; there, the real purchasing power of $15 ranges from $11.80 to $12.03.

In general, price levels are highest in urban areas and on the coasts – not coincidentally, areas where the push for a $15 minimum wage has been particularly strong. The three most expensive metropolitan areas in the country are all in and around the San Francisco Bay Area; there, the real purchasing power of $15 ranges from $11.80 to $12.03.

Beckley, West Virginia, has the lowest RPP of any metro area in the nation; a $15 hourly wage there has real purchasing power of $19.04. Austin-Round Rock, Texas, and Vineland-Bridgeton, New Jersey, have RPPs of exactly 100, making them the only metro areas where $15 really means $15.

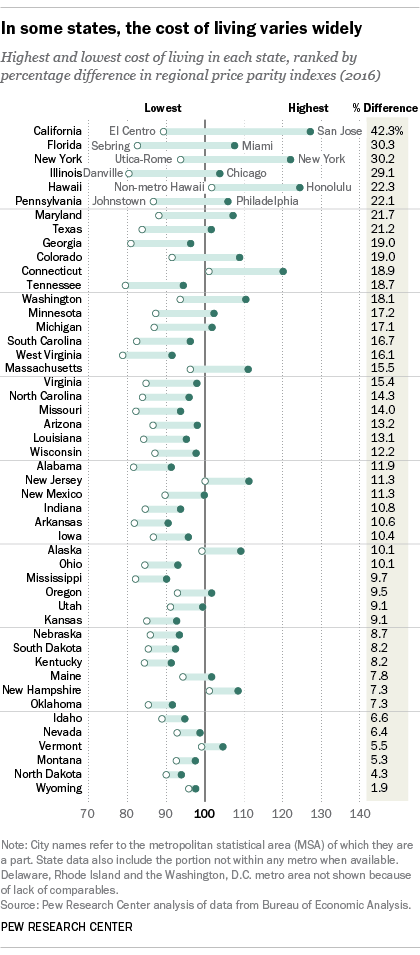

Living costs not only vary widely throughout the country, they can vary a lot within individual states as well. In California, the priciest metro area (San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara, more or less synonymous with Silicon Valley) is 42.3% more expensive than the least costly (El Centro, in the Imperial Valley across the border from Mexicali, Mexico). Metropolitan Miami is 30.3% more expensive than Sebring, Florida, roughly three hours to the northwest.

Giving low-paid workers everywhere in the country the same real purchasing power would require hundreds of different minimum wages, scaled to each locality’s cost of living. For example, giving everyone the same purchasing power that $15 has in Pittsburgh would translate to $19.41 in New York City and $16.51 in Chicago, but just $13.46 in Fort Smith, Arkansas.

Americans generally support raising the federal minimum wage, which has been set at $7.25 an hour since 2009. In an August 2016 Pew Research Center survey, 58% of Americans said they favored increasing the federal minimum to $15 an hour, versus 41% who opposed such a move. Among registered voters, however, the split was narrower, with 52% in favor and 46% opposed. As with many other issues, voters divided sharply along political, racial/ethnic and income lines.

States remain free to enact their own, higher minimum wages, and 29 of them (plus the District of Columbia) have done so, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. These include all but two of the 14 states with above-average RPPs (the exceptions being New Hampshire and Virginia). Laws in D.C. and three states – California, Massachusetts and New York – include scheduled future increases to bring their minimums to $15 over the next several years.

Note: This is an update of a post originally published Aug. 3, 2015.