The coronavirus outbreak stopped much of the world in its tracks in early 2020 and continues to cast doubt on the well-being of households and communities around the globe. But even before the pandemic, many people around the world felt pessimistic about income inequality, governance and job opportunities, according to a survey conducted by Pew Research Center in spring 2019.

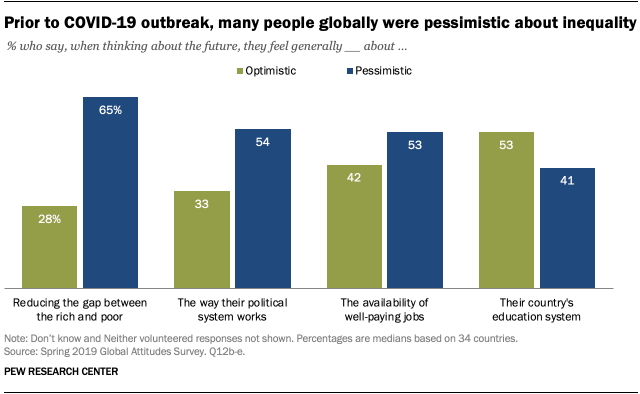

Across 34 countries surveyed, a median of 65% of adults said they felt generally pessimistic about reducing the gap between the rich and the poor in their country. Many also held doubts about the way their political system works (median of 54%) and the availability of well-paying jobs in their country (53%). When it comes to their country’s education system, however, more people expressed optimism than pessimism (53% vs. 41%).

As the coronavirus outbreak has intensified, these four issues – inequality, politics, employment and education – have received new attention. The United Nations has cautioned that a lack of social protections could send millions back into poverty, while others have warned that the virus might harm democratic governance, lead to more job insecurity and force school closures across the globe.

This analysis focuses on how people around the world feel about the future of inequality, employment opportunities, education and politics in their country.

For this analysis, we used data from a survey conducted across 34 countries from May 13 to Oct. 2, 2019, totaling 38,426 respondents. The surveys were conducted face-to-face in Africa, Latin America and the Middle East, and on the phone in United States and Canada. In the Asia-Pacific region, face-to-face surveys were conducted in India, Indonesia and the Philippines, while phone surveys were administered in Australia, Japan and South Korea. In Europe, surveys were conducted over the phone in France, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden and the UK, but face-to-face in Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Slovakia and Ukraine.

Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology.

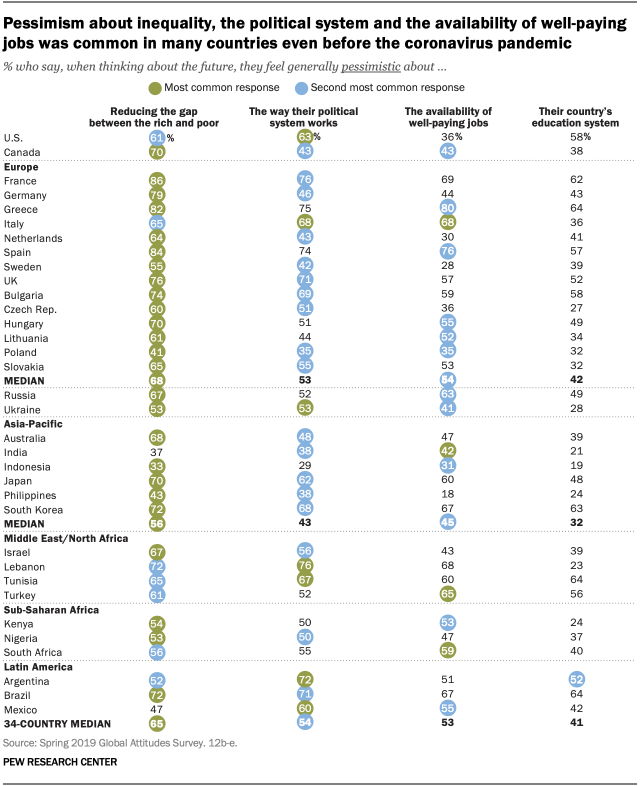

In 25 of the 34 countries surveyed by the Center in 2019, income inequality was the most common area of pessimism among respondents. In seven other countries, it was the second-most frequently named area of concern. In France, 86% of adults said they felt generally pessimistic about reducing the gap between the rich and the poor – the highest share across the countries surveyed. Around eight-in-ten or more also said this in Spain (84%), Greece (82%) and Germany (79%).

Worldwide, many people also expressed pessimism about governance. In 24 of 34 countries, majorities or pluralities said they were pessimistic about the future of their nation’s political system. This view was especially common in some countries that have experienced high-profile political crises recently, including the UK (Brexit), the United States (impeachment), Lebanon (WhatsApp tax protests), Argentina (inflation) and Brazil (Amazon fires).

When it comes to the availability of well-paying jobs in the future, more people globally saw this negatively than positively. However, in some countries – including the U.S., Sweden, the Netherlands and the Philippines – the availability of well-paying jobs was a source of optimism.

In several countries, those who place themselves on the ideological left were more pessimistic about inequality than those on the ideological right. This divide was most pronounced in the U.S., where 81% of left-leaning respondents were concerned about a need to reduce inequality, compared with 42% on the right.

While all ideological groups were generally pessimistic in the countries surveyed, there were also large divides between left and right in Hungary (33 percentage points), Lithuania (23 points), Brazil (20 points), the UK (19 points) and Israel (19 points).

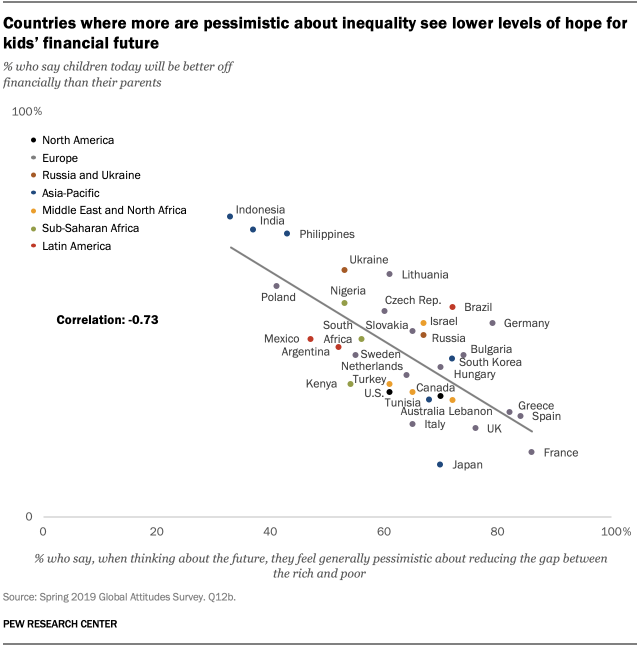

Attitudes about reducing inequality were also tied to views about children’s financial future. In countries where people tended to be pessimistic about reducing inequality, people also tended to be less optimistic about the financial future of their country’s children.

Note: Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology.