Black Americans are far more likely than whites to say the nation’s criminal justice system is racially biased and that its treatment of minorities is a serious national problem.

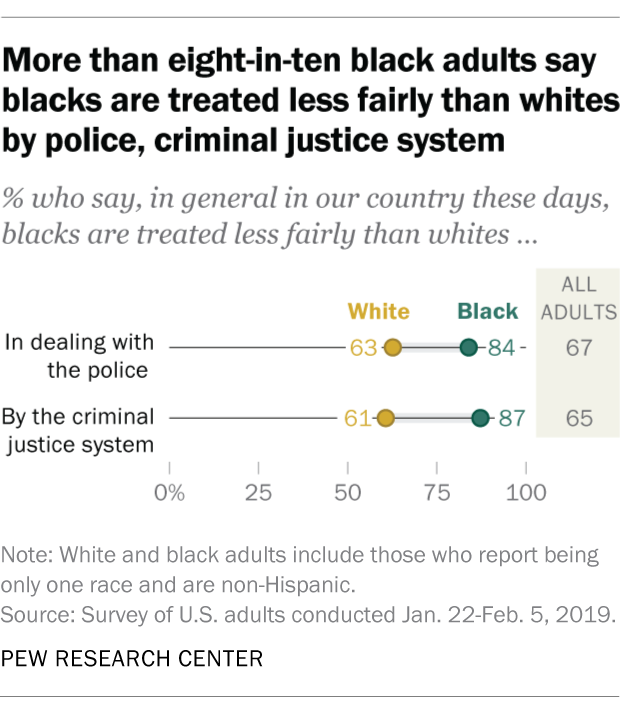

In a recent Pew Research Center survey, around nine-in-ten black adults (87%) said blacks are generally treated less fairly by the criminal justice system than whites, a view shared by a much smaller majority of white adults (61%). And in a survey shortly before last year’s midterm elections, 79% of blacks – compared with 32% of whites – said the way racial and ethnic minorities are treated by the criminal justice system is a very big problem in the United States today.

Racial differences in views of the criminal justice system are not limited to the perceived fairness of the system as a whole. Black and white adults also differ across a range of other criminal justice-related questions asked by the Center in recent years, on subjects ranging from crime and policing to the use of computer algorithms in parole decisions.

Here’s an overview of these racial differences:

Crime

Black adults in the U.S. consistently express more concern than white adults about crime.

In last year’s preelection survey, three-quarters of blacks – compared with fewer than half of whites (46%) – said violent crime is a very big problem in the country today. And while 82% of blacks said gun violence is a very big problem in the U.S., just 47% of whites said the same.

In last year’s preelection survey, three-quarters of blacks – compared with fewer than half of whites (46%) – said violent crime is a very big problem in the country today. And while 82% of blacks said gun violence is a very big problem in the U.S., just 47% of whites said the same.

Blacks are also more likely than whites to see crime as a serious problem locally. In an early 2018 survey, black adults were roughly twice as likely as whites to say crime is a major problem in their local community (38% vs. 17%).

That’s consistent with a survey conducted in early 2017, when blacks were about twice as likely as whites to say their local community is not too or not at all safe from crime (34% vs. 15%). Black adults were also more likely than whites to say they worry a lot about having their home broken into (28% vs. 13%) or being the victim of a violent crime (20% vs. 8%). However, similar shares in both groups (22% of blacks and 18% of whites) said they actually had been the victim of a violent crime.

Policing

Some of the most pronounced differences between blacks and whites emerge on questions related to police officers and the work they do.

A survey conducted in mid-2017 asked Americans to rate police officers and other groups of people on a “feeling thermometer” from 0 to 100, where 0 represents the coldest, most negative rating and 100 represents the warmest and most positive. Black adults gave police officers a mean rating of 47; whites gave officers a mean rating of 72.

Blacks are also more likely than whites to have specific criticisms about the way officers do their jobs, particularly when it comes to police interactions with their community.

In the Center’s survey earlier this year, 84% of black adults said that, in dealing with police, blacks are generally treated less fairly than whites. A much smaller share of whites – though still a 63% majority – said the same. Blacks were also about five times as likely as whites to say they’d been unfairly stopped by police because of their race or ethnicity (44% vs. 9%), with black men especially likely to say this (59%).

In the Center’s survey earlier this year, 84% of black adults said that, in dealing with police, blacks are generally treated less fairly than whites. A much smaller share of whites – though still a 63% majority – said the same. Blacks were also about five times as likely as whites to say they’d been unfairly stopped by police because of their race or ethnicity (44% vs. 9%), with black men especially likely to say this (59%).

Stark racial differences about key aspects of policing also emerged in a 2016 survey. Blacks were much less likely than whites to say that police in their community do an excellent or good job using the right amount of force in each situation (33% vs. 75%), treating racial and ethnic groups equally (35% vs. 75%) and holding officers accountable when misconduct occurs (31% vs. 70%). Blacks were also substantially less likely than whites to say their local police do an excellent or good job at protecting people from crime (48% vs. 78%).

Notably, black-white differences in views of policing exist among officers themselves. In a survey of nearly 8,000 sworn officers conducted in the fall of 2016, black officers were about twice as likely as white officers (57% vs. 27%) to say that high-profile deaths of black people during encounters with police were signs of a broader problem, not isolated incidents. And roughly seven-in-ten black officers (69%) – compared with around a quarter of white officers (27%) – said the protests that followed many of these incidents were motivated some or a great deal by a genuine desire to hold police accountable for their actions, rather than by long-standing bias against the police. (Several other questions in the survey also showed stark differences in the views of black and white officers.)

The death penalty

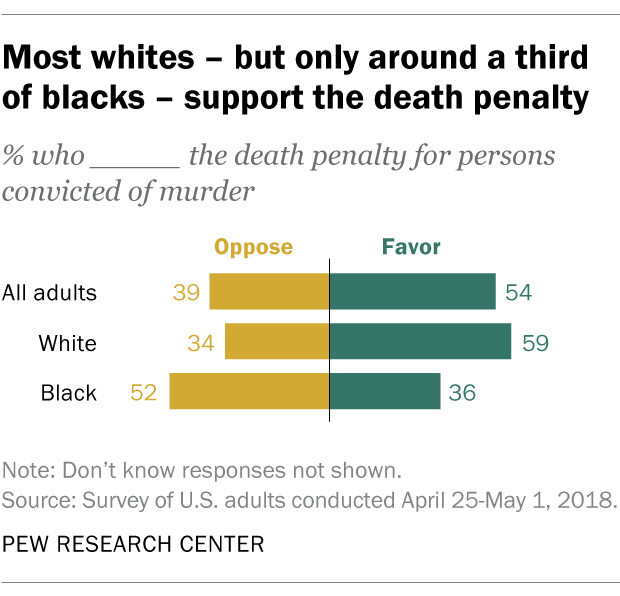

A narrow majority of Americans (54%) support the death penalty for people convicted of murder, according to a spring 2018 survey. But only around a third of blacks (36%) support capital punishment for this crime, compared with nearly six-in-ten whites (59%).

A narrow majority of Americans (54%) support the death penalty for people convicted of murder, according to a spring 2018 survey. But only around a third of blacks (36%) support capital punishment for this crime, compared with nearly six-in-ten whites (59%).

Racial divisions extend to other questions related to the use of capital punishment. In a 2015 survey, 77% of blacks said minorities are more likely than whites to be sentenced to death for committing similar crimes. Whites were divided on this question: 46% said minorities are disproportionately sentenced to death, while the same percentage saw no racial disparities.

Blacks were also more likely than whites to say capital punishment is not a crime deterrent (75% vs. 60%) and were less likely to say the death penalty is morally justified (46% vs. 69%). However, about seven-in-ten in both groups said they saw some risk in putting an innocent person to death (74% of blacks vs. 70% of whites).

Parole decisions

Certain aspects of the criminal justice system have changed in recent decades. One example: Some states now use criminal risk assessments to assist with parole decisions. These assessments involve collecting data about people who are up for parole, comparing that data with data about other people who have been convicted of crimes, and then assigning inmates a score to help decide whether they should be released from prison or not.

A 2018 survey asked Americans whether they felt the use of criminal risk assessments in parole decisions was an acceptable use of algorithmic decision-making. A 61% majority of black adults said using these assessments is unfair to people in parole hearings, compared with 49% of white adults.

Voting rights for ex-felons

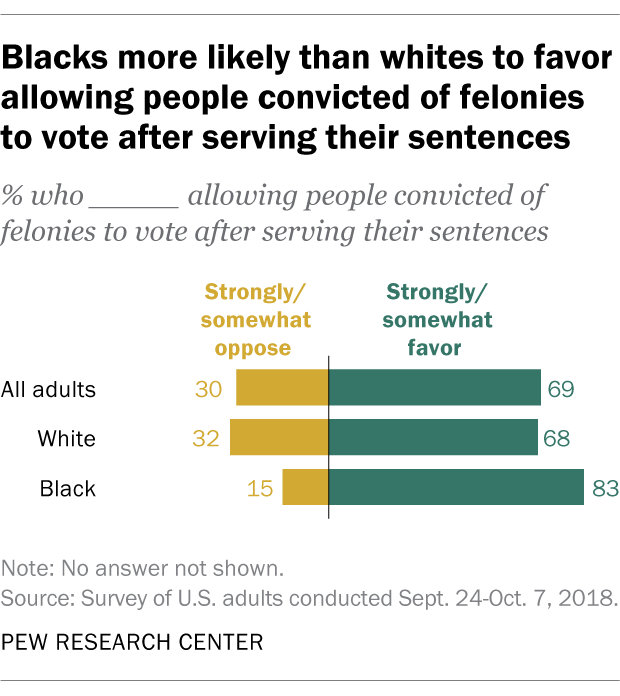

States differ widely when it comes to allowing people with past felony convictions to vote. In 12 states, people with certain felony convictions can lose the right to vote indefinitely unless other criteria – such as receiving a pardon from the governor – are met, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. In Maine and Vermont, by contrast, those with felony convictions never lose the right to vote, even while they are incarcerated. Twenty-two states fall somewhere between these positions, rescinding voting rights only during incarceration and for a period afterward, such as when former inmates are on parole.

In a fall 2018 survey, 69% of Americans favored allowing people convicted of felonies to vote after serving their sentences. Black adults were much more likely than white adults to somewhat or strongly favor this approach (83% vs. 68%).