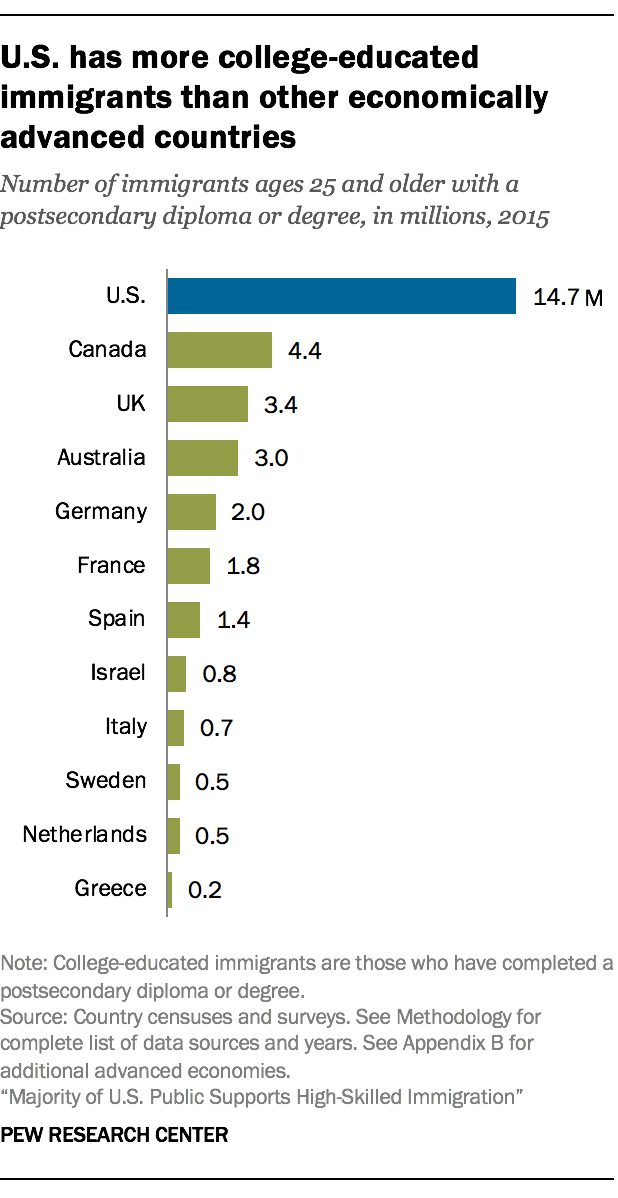

The United States is home to more college-educated immigrants than any other country. As of 2015, there were 14.7 million immigrants ages 25 and older with a postsecondary diploma or college degree living in the U.S. – more than triple the number in Canada (4.4 million) and more than four times as many as in the United Kingdom (3.4 million), according to a recent Pew Research Center report.

The United States is home to more college-educated immigrants than any other country. As of 2015, there were 14.7 million immigrants ages 25 and older with a postsecondary diploma or college degree living in the U.S. – more than triple the number in Canada (4.4 million) and more than four times as many as in the United Kingdom (3.4 million), according to a recent Pew Research Center report.

But the U.S. stands out less when looking at college-educated immigrants as a share of its overall foreign-born population. About a third (36%) of all immigrants in the U.S. have a college degree, well below the shares in Canada (65%), the UK (49%) and other economically advanced countries with substantial numbers of immigrants.

President Donald Trump has expressed his support for the immigration of “talented and highly skilled people” to the U.S., and the American public appears to share that view. In a spring 2018 survey conducted as part of the Center’s recent report, 78% of U.S. adults said they support encouraging highly skilled people to immigrate to and work in the country. More than eight-in-ten Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (83%) said this, as did 73% of Republicans and GOP leaners.

Here’s a brief overview of four paths that many highly educated immigrants take to study and work in the U.S.: the H-1B visa program, the F-1 visa program, the Optional Practical Training program and green cards. These are not the only avenues that highly educated immigrants can take to enter the U.S., but they are among the most common.

H-1B visas

Created by the Immigration Act of 1990, the H-1B program is the nation’s biggest visa program for temporary employment of foreign-born workers who have specialized knowledge and a bachelor’s degree or higher. It allows U.S. employers to hire foreigners to work on a temporary basis.

Created by the Immigration Act of 1990, the H-1B program is the nation’s biggest visa program for temporary employment of foreign-born workers who have specialized knowledge and a bachelor’s degree or higher. It allows U.S. employers to hire foreigners to work on a temporary basis.

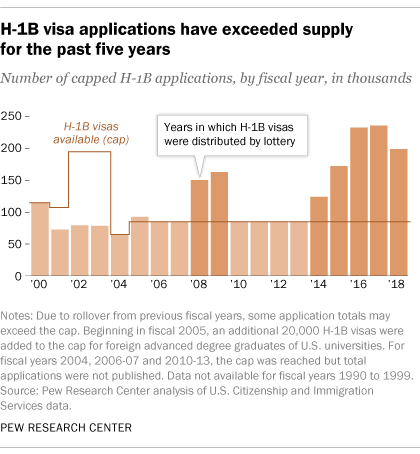

H-1B visas are awarded directly to companies (rather than to individuals) on a first-come, first-served basis. Since 2005, Congress has set an annual cap of 65,000 such visas per year, plus an additional 20,000 H-1B visas per year for foreigners who have a graduate degree from a U.S. academic institution. The Department of Homeland Security recently issued a rule that changes the way H-1B petitions are selected, prioritizing individuals with U.S. graduate degrees. H-1B visas are good for up to six years and can be renewed if the visa holder has a pending application for permanent residency in the U.S.

Demand for H-1B workers has soared in recent years, with far more applications than available visas. In fact, in each of the past five years, the program’s cap has been reached within a week of the application period opening, which occurs in April each year.

Between fiscal 2001 and fiscal 2015, more than half (50.5%) of all H-1B visas for first-time employment were issued to Indian nationals. The share of these visas issued to workers from India far outpaced the share issued to workers from China (9.7%), the next largest origin group. Smaller shares were awarded to workers from Canada (3.8%), the Philippines (3.0%) and South Korea (2.8%).

F-1 visas

The most common type of foreign student visa is the F-1 visa, typically given to those pursuing college degrees in the U.S., including associate, bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees.

The most common type of foreign student visa is the F-1 visa, typically given to those pursuing college degrees in the U.S., including associate, bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees.

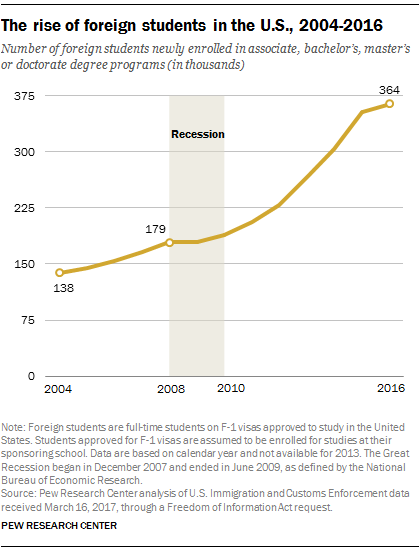

Since the Great Recession, there has been dramatic growth in the number of foreign students who are newly enrolled at U.S. colleges and universities through F-1 visas. There were nearly 364,000 such students in 2016, more than double the number in 2008. This 104% growth rate compares with a growth rate of 3.4% in overall college enrollment during the same period. The number of foreign students on F-1 visas grew sharply at both public and private academic institutions, but it grew more quickly at public colleges and universities than at private ones (107% vs. 98% growth between 2008 and 2016).

Around half (49%) of all newly enrolled foreign students in 2016 were pursuing graduate-level degrees, including 41% who were working toward master’s degrees and 8% who were pursuing doctoral degrees. Another 38% were pursuing bachelor’s degrees while 13% were seeking associate degrees. Students from China, India and South Korea accounted for more than half (54%) of all new foreign students pursuing U.S. higher education degrees in 2016.

You can learn more about the F-1 visa program with this fact sheet.

Optional Practical Training

The OPT program allows foreigners who are full-time students at American colleges and universities to remain in the country on a temporary basis to gain practical work experience after they graduate. Unlike the H-1B program, the OPT program does not require applicants to be sponsored by an employer, and it does not set a cap on the number of people who can participate. But the duration of legal residence under OPT is shorter than it is under H-1B: Participants may work in the U.S. for 12 months after graduation, extendable to a maximum of 36 months for those with a degree in a science, technology, engineering or math (STEM) field.

The OPT program allows foreigners who are full-time students at American colleges and universities to remain in the country on a temporary basis to gain practical work experience after they graduate. Unlike the H-1B program, the OPT program does not require applicants to be sponsored by an employer, and it does not set a cap on the number of people who can participate. But the duration of legal residence under OPT is shorter than it is under H-1B: Participants may work in the U.S. for 12 months after graduation, extendable to a maximum of 36 months for those with a degree in a science, technology, engineering or math (STEM) field.

The OPT program has become an increasingly popular pathway for foreign graduates of U.S. colleges to remain in the country. In recent years, the number of people approved for OPT has surpassed the number of workers who received initial approval for H-1B visas. In 2017, a record 276,500 foreign graduates received work permits under OPT, compared with 108,100 people who received initial approval for H-1B visas.

College graduates from India and China accounted for the vast majority of OPT approvals in 2017. Nearly 70% of all OPT approvals involved graduates from these two countries, far outpacing the number from South Korea, Canada and other nations. Notably, however, 2017 saw a considerable slowdown in the growth of the program: The number of enrollees grew by 8% in 2017, down from 34% growth the prior year. The Trump administration has tightened regulations that govern the OPT program.

Explore where foreign student graduates work using OPT in the United States by metro area with this interactive feature.

Green cards

Many college-educated immigrants also live and work in the U.S. through green cards, which provide lawful permanent residence to around a million foreign-born people each year based on a complex system of admission categories and quotas. It’s important to note that green cards are not specific to college-educated foreigners: They are available to immigrants regardless of their educational background.

Around two-thirds (66%) of all new green cards issued in fiscal 2017 went to immigrants who were sponsored by family members, while 13% went to refugees or asylum seekers. Employment-related categories accounted for 12% of the green cards issued in 2017 – including those with employment-based green cards, workers’ family members and those previously sponsored under the H-1B visa program.

It’s not clear how many workers on H-1B visas went on to receive green cards in 2017, but a report by the Bipartisan Policy Center found that H-1B holders accounted for around a third (36%) of the employment-related green cards that were issued between fiscal 2010 and 2014.