Studies have often credited religion with making people healthier, happier and more engaged in their communities. But are religiously active people better off than those who are religiously inactive or those with no religious affiliation? The short answer is that there is some evidence that religious participation does make a difference in some – but not all – of these areas, according to a new Pew Research Center report that looks at survey data from the United States and more than two dozen other countries.

To shed more light on this question, researchers divided survey-takers into three categories: the “actively religious,” who identify with a religion and attend a house of worship at least monthly; the “inactively religious,” who identify with a religion but attend less frequently; and the unaffiliated (or “nones”), who do not identify with any religion.

Here are five findings about the relationship between religion and health, happiness and civic engagement:

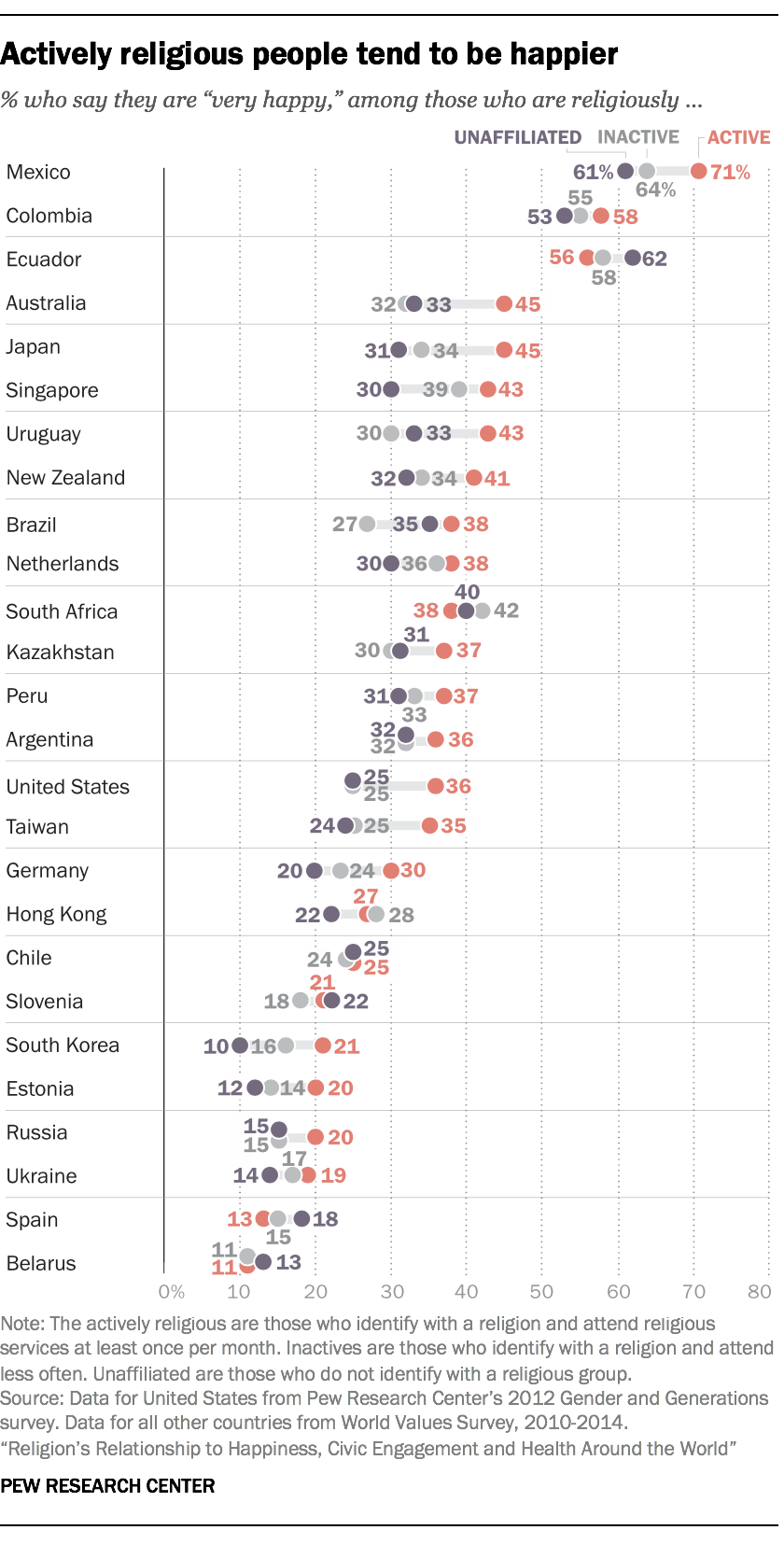

1 Actively religious people are more likely than their less-religious peers to describe themselves as “very happy” in about half of the countries surveyed. Sometimes the gaps are striking: In the U.S., for instance, 36% of the actively religious describe themselves as “very happy,” compared with 25% of the inactively religious and 25% of the unaffiliated. Notable happiness gaps among these groups also exist in Japan, Australia and Germany.

1 Actively religious people are more likely than their less-religious peers to describe themselves as “very happy” in about half of the countries surveyed. Sometimes the gaps are striking: In the U.S., for instance, 36% of the actively religious describe themselves as “very happy,” compared with 25% of the inactively religious and 25% of the unaffiliated. Notable happiness gaps among these groups also exist in Japan, Australia and Germany.

2 There is not a clear connection between religiosity and the likelihood that people will describe themselves as being in “very good” overall health. Even after controlling for factors that might affect the results, such as age, income and gender, there are only three countries out of the 26 where the actively religious are likely to report better health than everyone else — the U.S., Taiwan and Mexico. Religiously active people also don’t seem to be any healthier by two other, more specific measures: obesity and frequency of exercise.

3 At the same time, the actively religious are generally less likely than the unaffiliated to smoke and drink. Religions often frown on certain unhealthy behaviors, and that tendency seems reflected in data on smoking and drinking. In all but two of 19 countries for which data are available, the actively religious are less likely than the unaffiliated to smoke, and, in all but one country, less likely than the inactively religious to do so. The actively religious also tend to drink less, although the findings are not as stark: In 11 of the 19 countries, people who attend services at least monthly are less likely than the rest of the population to drink several times a week.

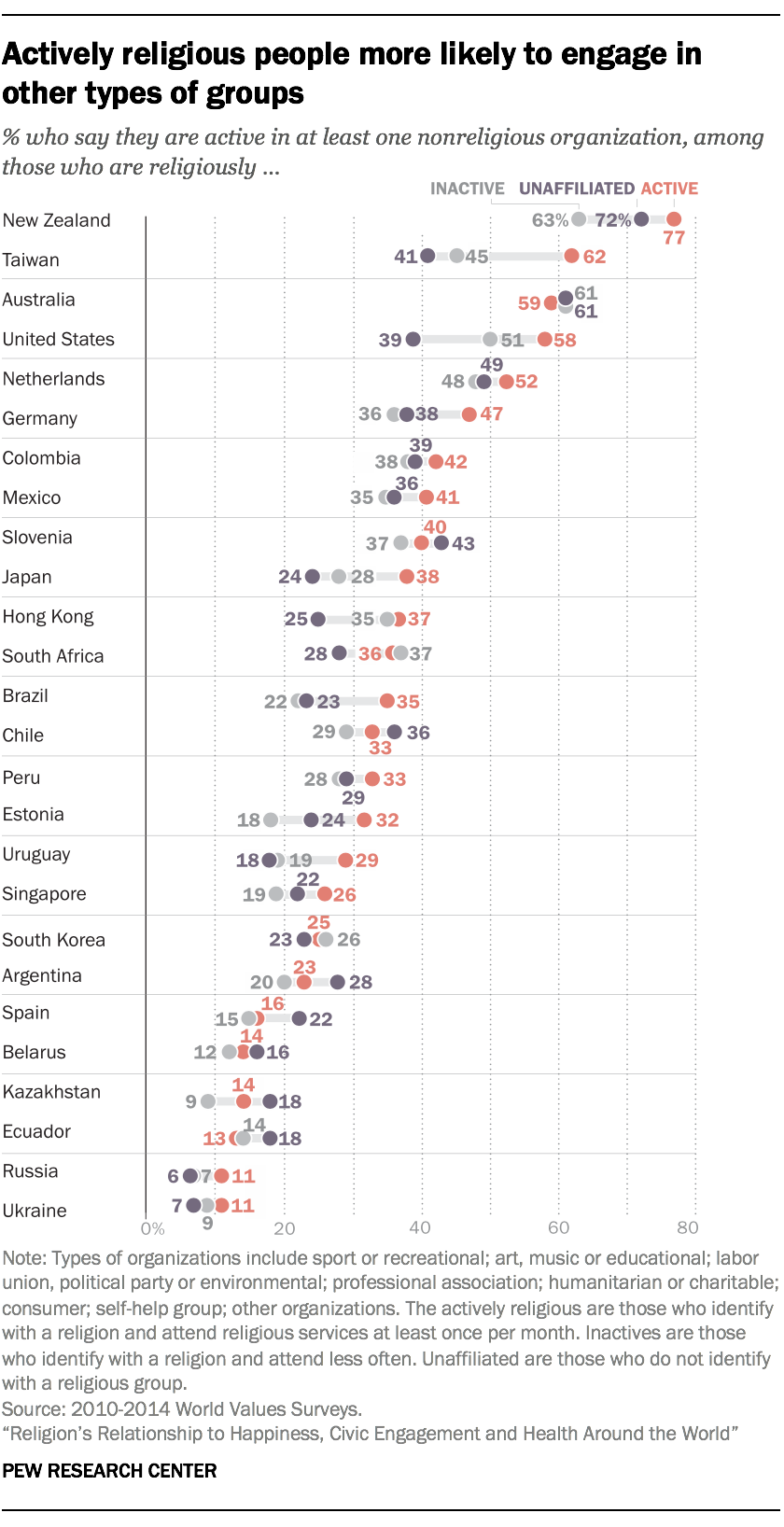

4 People who attend religious services at least monthly often are more likely than “nones” to join other types of (nonreligious) organizations, such as charities and clubs. This is true in eight of the 26 countries surveyed. And in 12 countries, the religiously active are more likely than inactively religious people to join nonreligious groups. In the U.S., for example, 58% of actively religious people are also involved in at least one nonreligious voluntary organization, compared with just 51% of the inactively religious and 39% of the unaffiliated.

4 People who attend religious services at least monthly often are more likely than “nones” to join other types of (nonreligious) organizations, such as charities and clubs. This is true in eight of the 26 countries surveyed. And in 12 countries, the religiously active are more likely than inactively religious people to join nonreligious groups. In the U.S., for example, 58% of actively religious people are also involved in at least one nonreligious voluntary organization, compared with just 51% of the inactively religious and 39% of the unaffiliated.

5 The actively religious generally are more likely than others to vote. In Spain, 83% of the actively religious report that they always vote in national elections, compared with 62% of inactives and 53% of the unaffiliated. In the U.S., 69% of the actively religious say they always vote, compared with 59% of inactives and 48% of the unaffiliated. In fact, there are no countries in which the actively religious are significantly less likely to vote than others. Countries where there are no significant differences in voting patterns by religion include Brazil, the Netherlands and New Zealand, as well as several other countries where voting is mandatory.