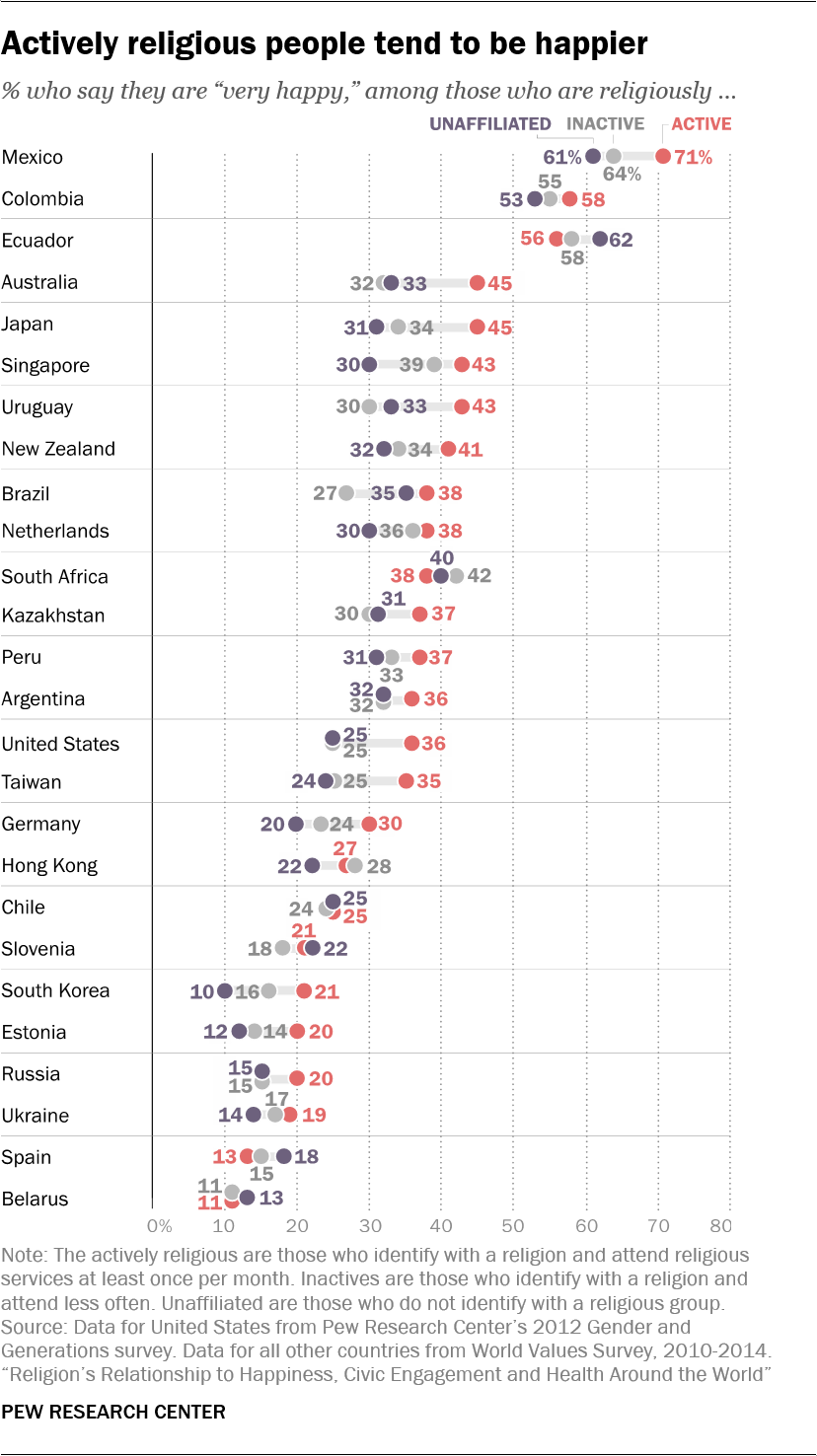

People who are active in religious congregations tend to be happier and more civically engaged than either religiously unaffiliated adults or inactive members of religious groups, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of survey data from the United States and more than two dozen other countries.

People who are active in religious congregations tend to be happier and more civically engaged than either religiously unaffiliated adults or inactive members of religious groups, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of survey data from the United States and more than two dozen other countries.

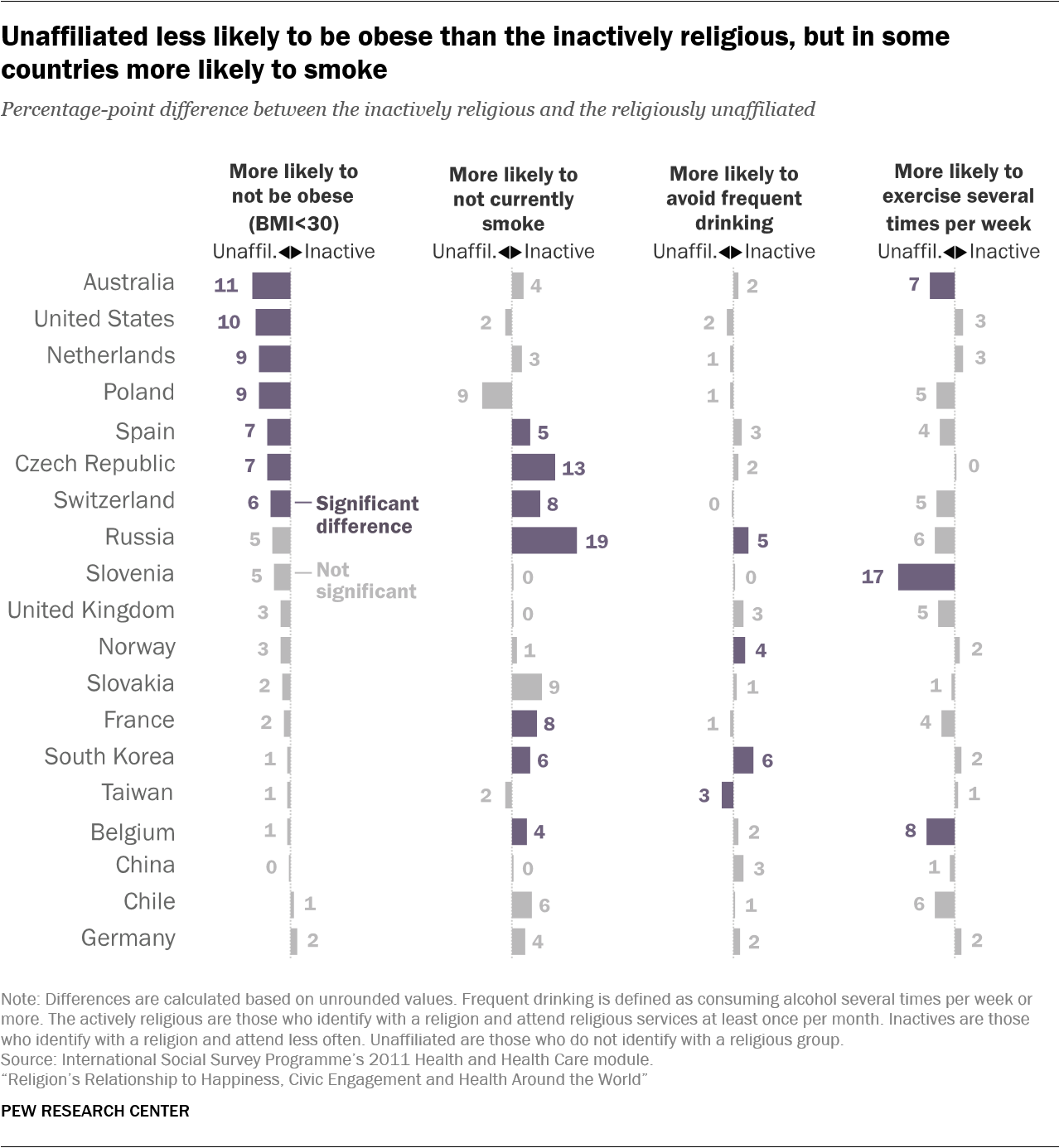

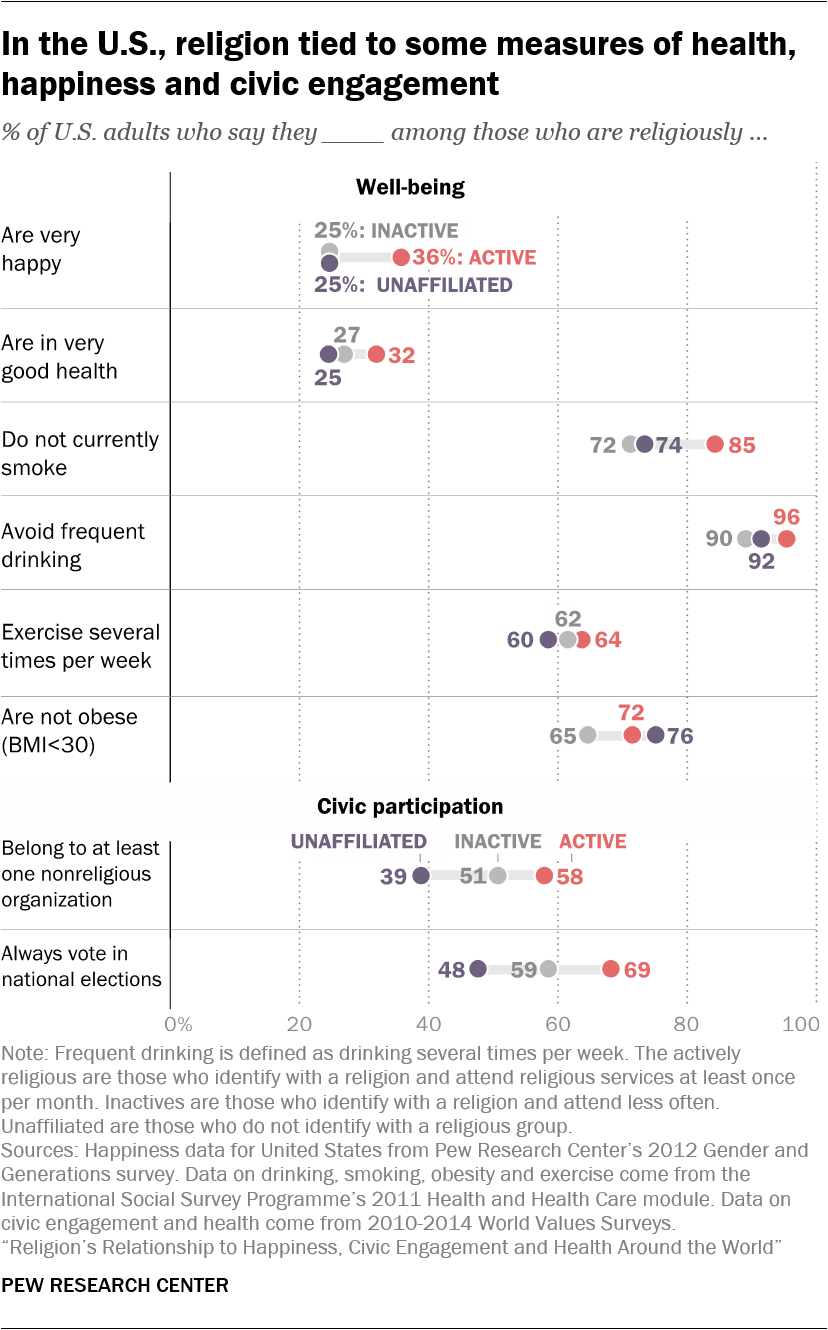

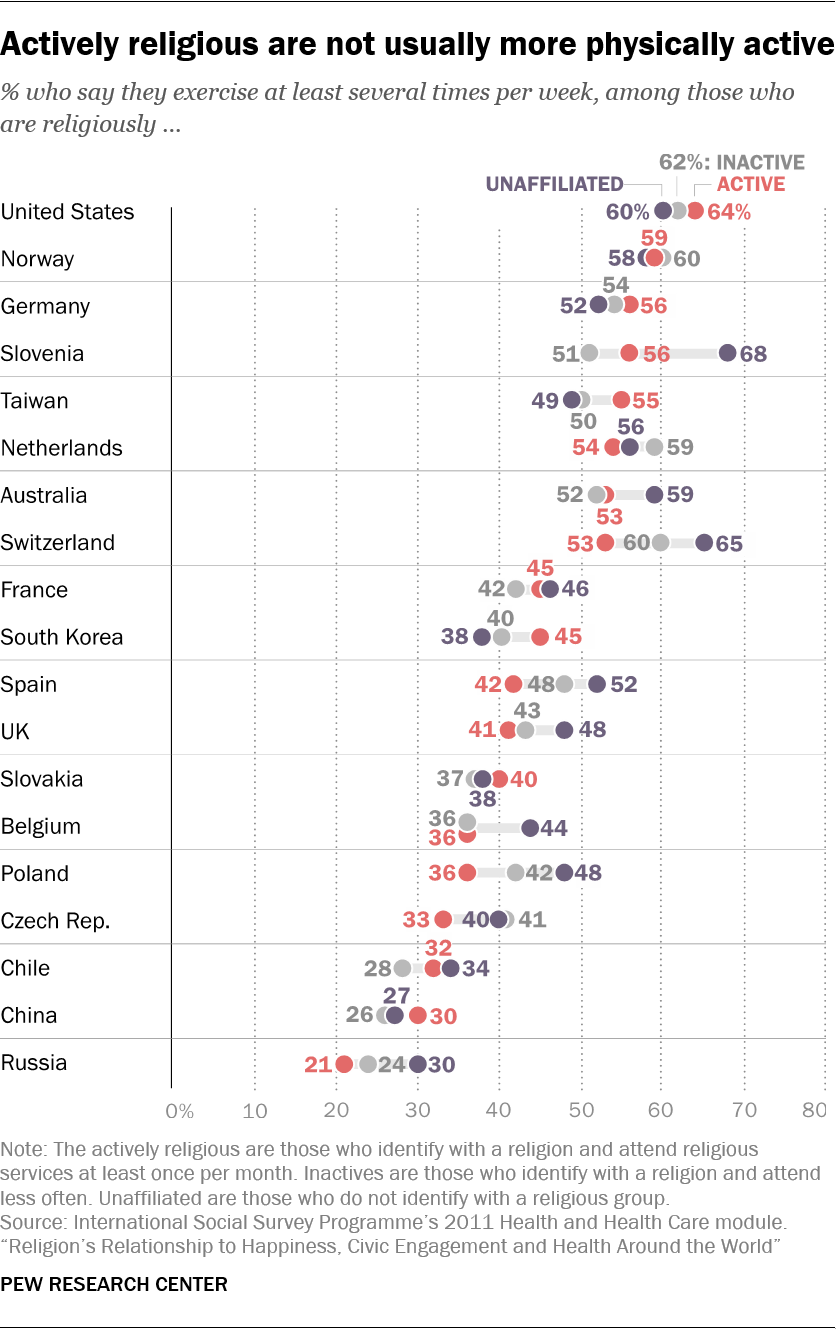

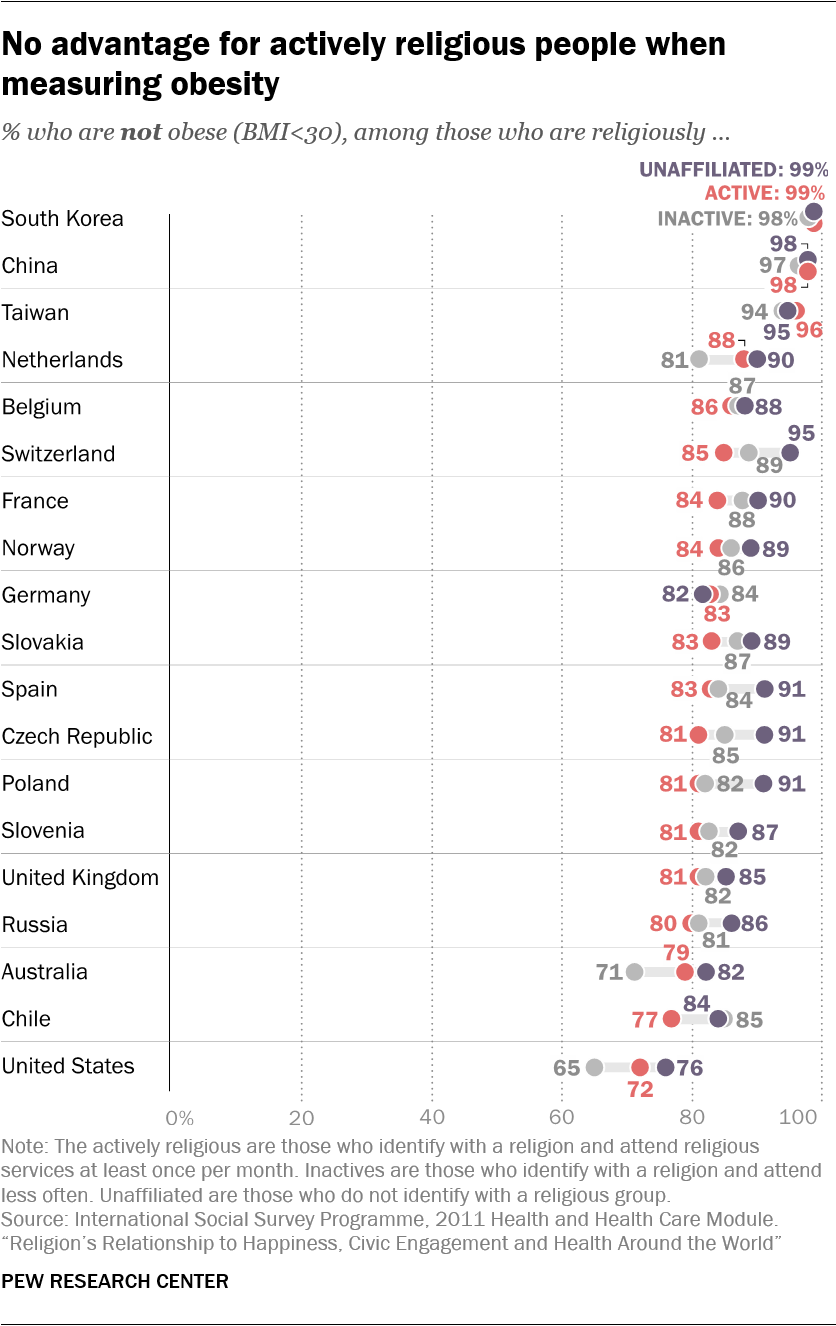

Religiously active people also tend to smoke and drink less, but they are not healthier in terms of exercise frequency and rates of obesity. Nor, in most countries, are highly religious people more likely to rate themselves as being in very good overall health – though the U.S. is among the possible exceptions.

Many previous studies have found positive associations between religion and health in the United States. Researchers have shown, for example, that Americans who regularly attend religious services tend to live longer.1 Other studies have focused on narrower health benefits, such as how religion may help breast cancer patients cope with stress. On the other hand, there are also studies that have not found a robust relationship between religion and better health in the U.S., and even some studies that have shown negative relationships, such as higher rates of obesity among highly religious Americans. (For more on previous studies of religion and health, see this sidebar.)

Taking a broad, international approach to this complicated topic, Pew Research Center researchers set out to determine whether religion has clearly positive, negative or mixed associations with eight different indicators of individual and societal well-being available from international surveys conducted over the past decade. Specifically, this report examines survey respondents’ self-assessed levels of happiness, as well as five measures of individual health and two measures of civic participation.2

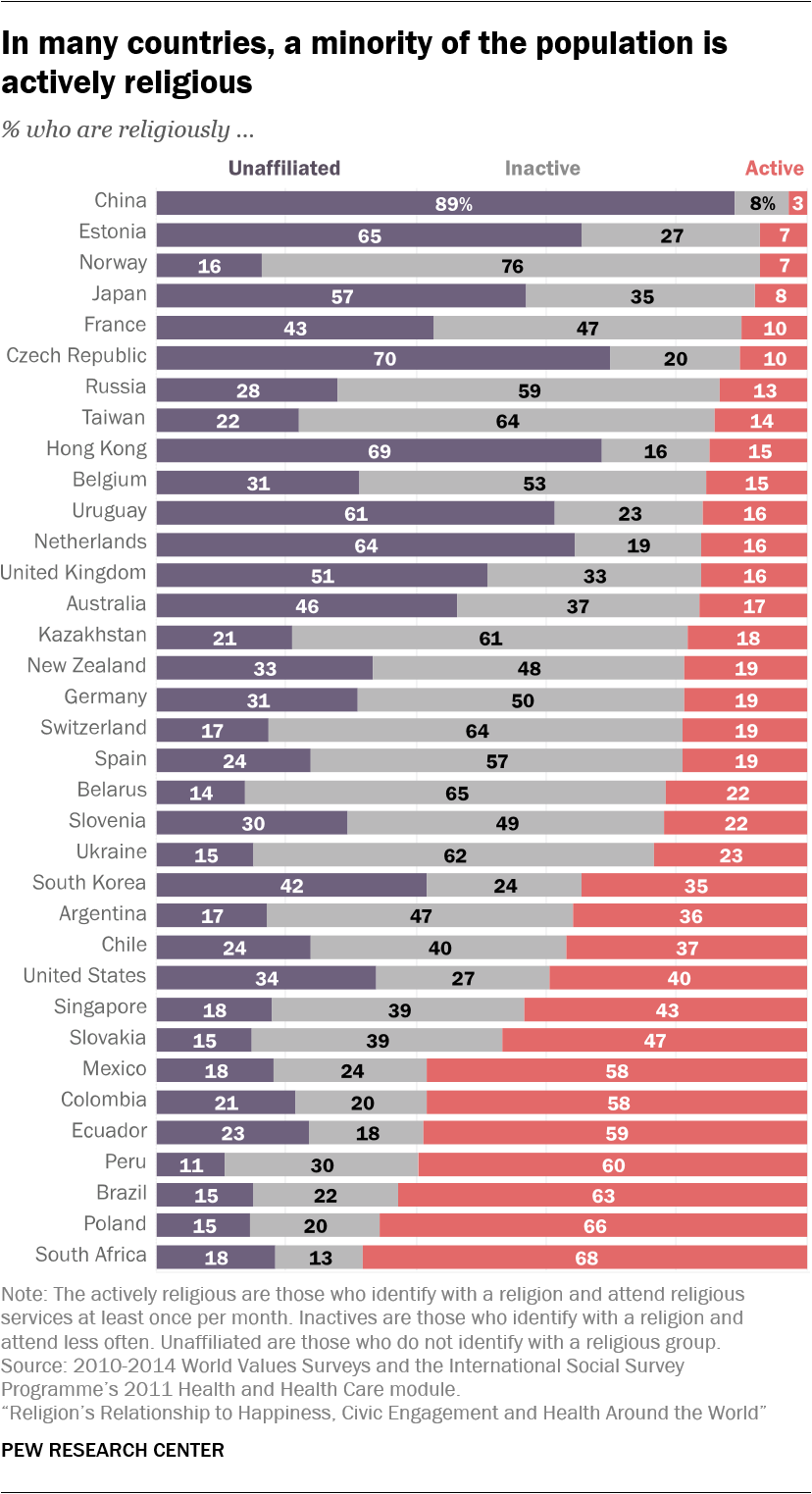

By dividing people into three categories, the study also seeks to isolate whether religious affiliation or religious participation – or both, or neither – is associated with happiness, health and civic engagement. The three categories are: “Actively religious,” made up of people who identify with a religious group and say they attend services at least once a month (sometimes called “actives”); “inactively religious,” defined as those who claim a religious identity but attend services less often (also called “inactives”); and “religiously unaffiliated,” people who do not identify with any organized religion (sometimes called “nones”).3

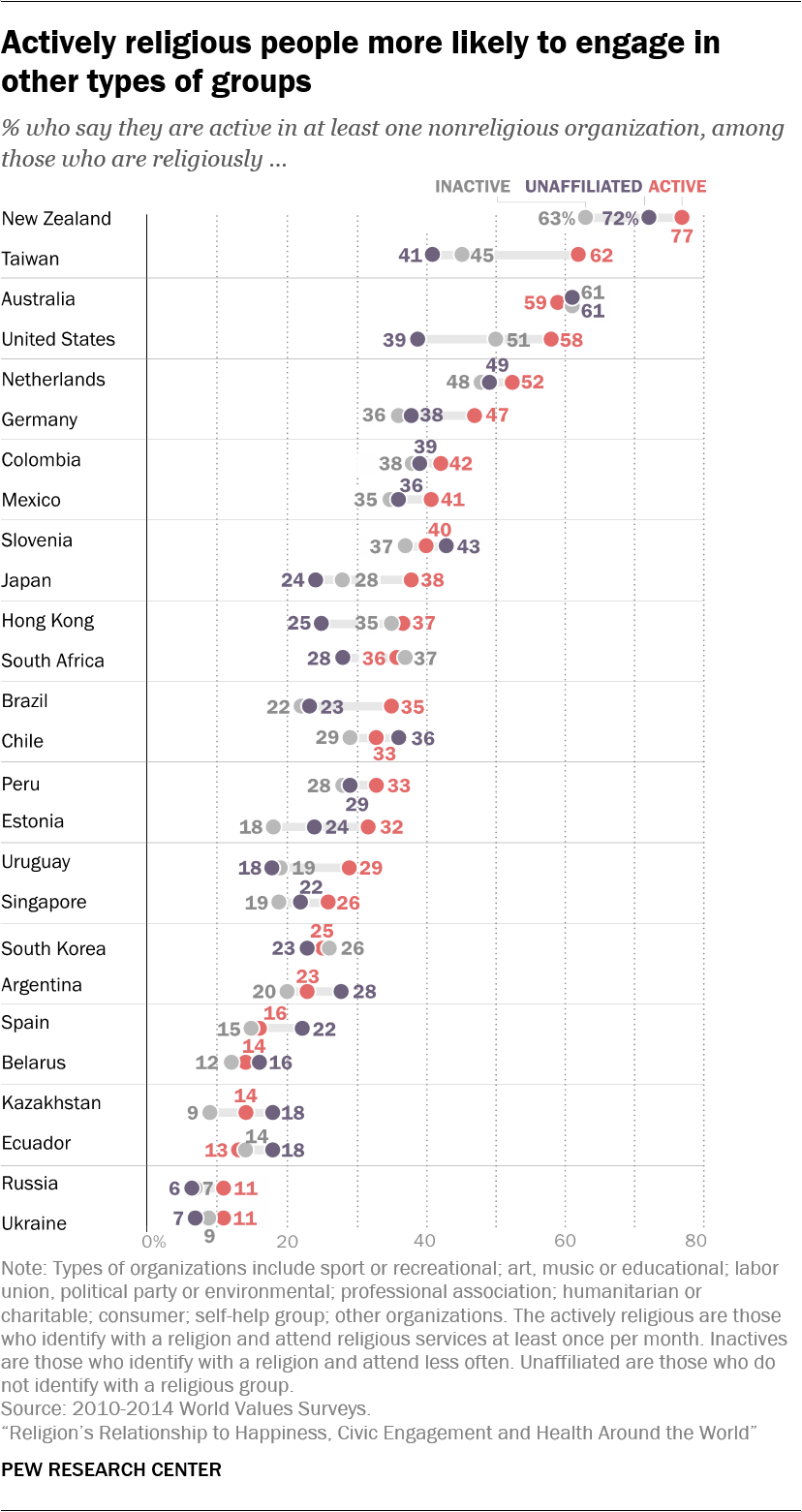

This analysis finds that in the U.S. and many other countries around the world, regular participation in a religious community clearly is linked with higher levels of happiness and civic engagement (specifically, voting in elections and joining community groups or other voluntary organizations). This may suggest that societies with declining levels of religious engagement, like the U.S., could be at risk for declines in personal and societal well-being. But the analysis finds comparatively little evidence that religious affiliation, by itself, is associated with a greater likelihood of personal happiness or civic involvement.

Moreover, there is a mixed picture on the five health measures. In the U.S. and elsewhere, actively religious people are less likely than others to engage in certain behaviors that are sometimes viewed as sinful, such as smoking tobacco and drinking alcohol. But religious activity does not have a clear association with how often people exercise or whether they are obese. And, after adjusting for differences in age, education, income and other factors, there is no statistical link between being actively religious and being in better self-reported overall health in any of the 26 countries and territories studied except Taiwan, Mexico and the United States.4

Moreover, there is a mixed picture on the five health measures. In the U.S. and elsewhere, actively religious people are less likely than others to engage in certain behaviors that are sometimes viewed as sinful, such as smoking tobacco and drinking alcohol. But religious activity does not have a clear association with how often people exercise or whether they are obese. And, after adjusting for differences in age, education, income and other factors, there is no statistical link between being actively religious and being in better self-reported overall health in any of the 26 countries and territories studied except Taiwan, Mexico and the United States.4

Even in the U.S., the strength of the linkage between religion and health varies, depending on measures and datasets used. For example, in some years, the General Social Survey has shown that religiously affiliated people who go to church or other religious services at least once a month are particularly likely to report that they are in excellent overall health, while in other recent years this has not been the case. (See sidebar on the United States).

The exact nature of the connections between religious participation, happiness, civic engagement and health remains unclear and needs further study. While the data presented in this report indicate that there are links between religious activity and certain measures of well-being in many countries, the numbers do not prove that going to religious services is directly responsible for improving people’s lives. Rather, it could be that certain kinds of people tend to be active in multiple types of activities (secular as well as religious), many of which may provide physical or psychological benefits.5 Moreover, such people may be more active partly because they are happier and healthier, rather than the other way around. (For more information about what may be causing these links, see this sidebar.)

Whatever the explanation may be, more than one-third of actively religious U.S. adults (36%) describe themselves as very happy, compared with just a quarter of both inactive and unaffiliated Americans. Across 25 other countries for which data are available, actives report being happier than the unaffiliated by a statistically significant margin in almost half (12 countries), and happier than inactively religious adults in roughly one-third (nine) of the countries.

The gaps are often striking: In Australia, for example, 45% of actively religious adults say they are very happy, compared with 32% of inactives and 33% of the unaffiliated. And there is no country in which the data show that actives are significantly less happy than others (though in many countries, there is not much of a difference between the actives and everyone else).

When it comes to measuring civic participation, the results again follow a pattern: On balance, people who are actively religious are also more likely to be active in voluntary and community groups. This dovetails with previous studies in the United States.6

In the U.S., 58% of actively religious adults say they are also active in at least one other (nonreligious) kind of voluntary organization, including charity groups, sports clubs or labor unions. Only about half of all inactively religious adults (51%) and fewer than half of the unaffiliated (39%) say the same.7

In the U.S., 58% of actively religious adults say they are also active in at least one other (nonreligious) kind of voluntary organization, including charity groups, sports clubs or labor unions. Only about half of all inactively religious adults (51%) and fewer than half of the unaffiliated (39%) say the same.7

A similar pattern appears in many other countries for which data are available: Actively religious adults tend to be more involved in voluntary organizations. In 11 out of 25 countries analyzed outside of the U.S., actives are more likely than inactives to join community groups. And in seven of the countries, actively religious adults are more likely than those who are religiously unaffiliated to belong to voluntary organizations.

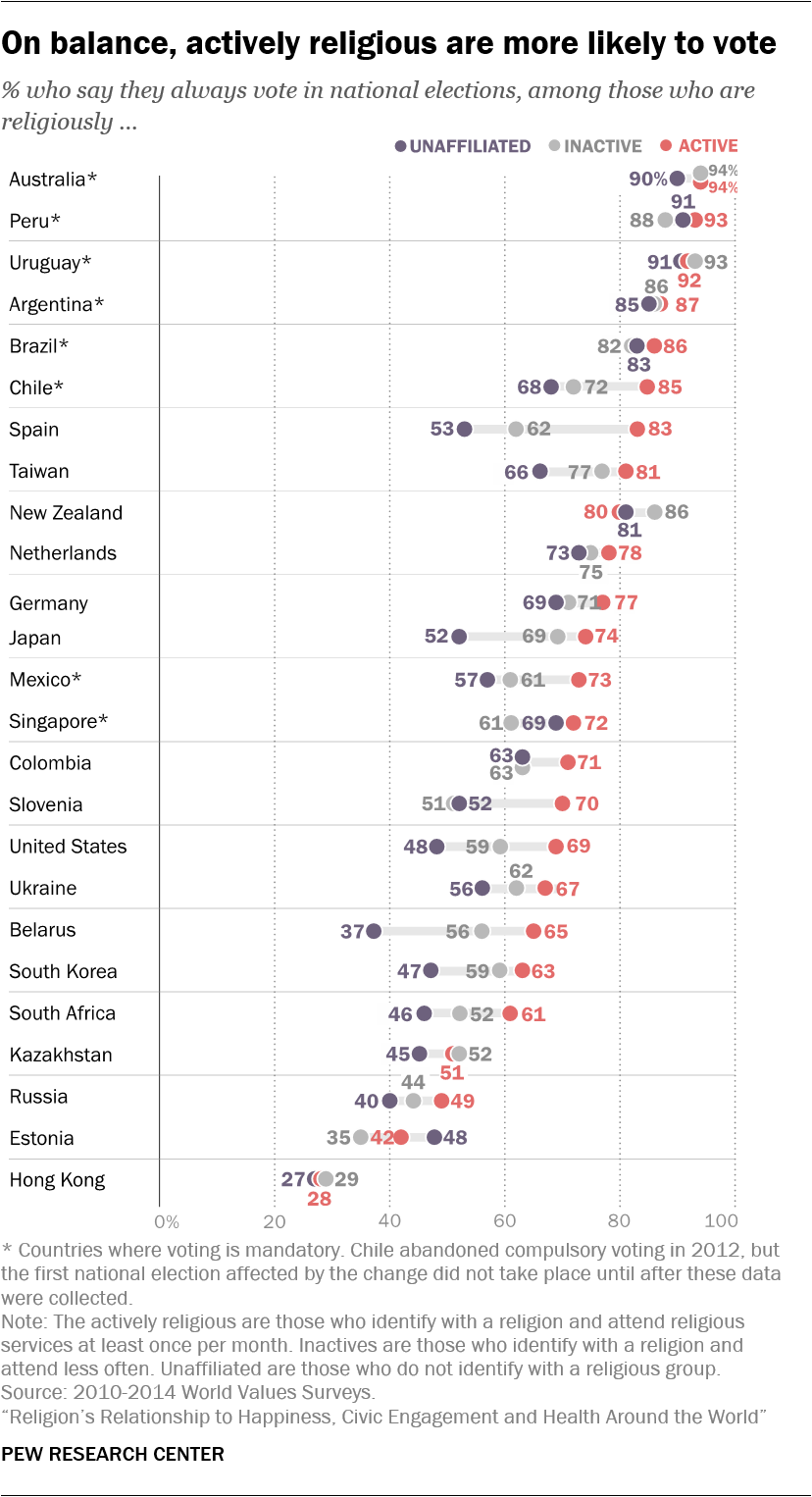

In addition, a higher percentage of actively religious adults in the United States (69%) say they always vote in national elections than do either inactives (59%) or the unaffiliated (48%).

Outside of the U.S., actively religious adults are more likely than “nones” to report voting in national elections in half the countries (12 out of 24) for which data on this measure are available; in the remaining countries, there is not much of a difference. Actives also are more likely than their inactive compatriots to say they vote in nine out of 24 countries, while the opposite is not true in any country for which data are available.8

Outside of the U.S., actively religious adults are more likely than “nones” to report voting in national elections in half the countries (12 out of 24) for which data on this measure are available; in the remaining countries, there is not much of a difference. Actives also are more likely than their inactive compatriots to say they vote in nine out of 24 countries, while the opposite is not true in any country for which data are available.8

These are among the key findings of a new analysis of data from cross-national surveys conducted since 2010 by Pew Research Center and two other organizations: the World Values Survey Association and the International Social Survey Programme. This report focuses on countries with sufficiently large populations of people who are actively religious, inactively religious and religiously unaffiliated to allow researchers to compare all three groups using the same survey data. As a result, the analysis cannot be truly global: 26 countries surveyed by the WVS are used to measure self-rated health, happiness and voluntary group participation; 25 countries, also surveyed by the WVS, are included for voting; and 19 countries surveyed by the ISSP are used to examine smoking, drinking alcohol, obesity and exercise. A Pew Research Center survey provides U.S. estimates for self-rated happiness. The countries analyzed are mostly Christian-majority nations in Europe and the Americas (because these countries tend to have substantial unaffiliated populations), though the analysis also includes a few African and Asian countries and territories, such as South Africa, South Korea and Japan.

An additional reason this study relies heavily on data from Christian-majority countries is that regular attendance at religious services – a key measure in this study – is a more central practice in some world religions (such as Christianity, Islam and Judaism) than in others (such as Hinduism or Buddhism, in which there is less emphasis on communal worship).

Social activity, religion and the happiness dividend

While in many countries religious activity seems to be connected with certain benefits, such as higher levels of happiness, it is unclear whether there is a direct, causal connection and, if so, exactly how it works.

Prior research suggests that one factor may be particularly important: The social connections that come with regular participation in group events, such as weekly worship services, Bible study groups, Sabbath dinners and Ramadan iftars.9 In an effort to understand why religion is related to happiness, Chaeyoon Lim of the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Robert Putnam of Harvard University examined data from a representative sample of American adults surveyed in 2006 and recontacted in 2007. The researchers found that religious participation had a strong impact on happiness among highly religious people with many friends in their congregations, but not among those with few friends in their congregations.10

The friendship networks fostered by religious communities create an asset that Putnam and other scholars call “social capital” – which not only makes people happier by giving them a sense of purpose and belonging, but also makes it easier for them to find jobs and build wealth. In other words, those who frequently attend a house of worship may have more people they can rely on for information and help during both good and bad times. Indeed, a range of social scientific research corroborates the idea that social support is pivotal to other aspects of well-being. For instance, one study found that religion indirectly boosts self-reported health because highly religious people had more social capital.11 Congregation-based relationships may help parishioners cope with stress and reinforce positive health behaviors.12

Similarly, research that examines the association between religion and mortality points to religious service participation as the key aspect of religion that promotes longevity. For instance, sociologist Jibum Kim and colleagues have found that regular service attendance is associated with reduced risk of mortality, while strength of religious affiliation, prayer, and religious beliefs have no effect.13 This association between service attendance and mortality is presumably due to the healthy behaviors and lack of risky behaviors among regular churchgoers. 14

Although social activity seems to be a key driver of well-being among religiously active people, there is plenty of research to suggest that other factors play a role, too. Some researchers argue that virtues promoted by religion, such as compassion, forgiveness and helping others, may improve happiness and even physical health if they are practiced by parishioners. Religion may benefit psychological well-being because it encourages supernatural beliefs that can help people deal with stress.15 Social psychologists identify “stress buffering” mechanisms, such as a perceived connection with the divine, as key ways people may deal with difficult life events.16 And religious meaning may help people manage suffering, both in their lives and in the lives of those around them.17 This appears to be particularly important for older people, who tend to experience suffering on a more regular basis.18

Other researchers argue that religion can more directly lead to better health by proscribing risky behaviors and promoting healthy ones.19 Many religions discourage members from excessive alcohol and drug use, for example.20 Some religions, such as the Seventh-day Adventist Church and certain schools of Buddhism and Hinduism, encourage specific behaviors that may have health benefits, such as a vegetarian diet, regular exercise and meditation.21

Finally, it could also be that religious activity is associated with greater well-being simply because happier, healthier people have more inclination and ability to be active in their communities, including religious groups. People who are unhappy and struggling physically or financially generally may be more isolated and less able to engage in social activities.

All of these explanations are not mutually exclusive: While it may be the case that happier and healthier people tend to be more involved in social groups of all kinds – secular as well as religious – it may also be true that individuals reap well-being benefits from the social connections they build in religious congregations and other aspects of religious involvement.

Actively religious people have some healthier behaviors, but not better self-rated health

When it comes to self-assessments of health, there is no clear pattern to indicate that either identifying with a religion or regularly attending religious services makes a significant difference in an international context.

When it comes to self-assessments of health, there is no clear pattern to indicate that either identifying with a religion or regularly attending religious services makes a significant difference in an international context.

In half of the countries analyzed, including South Africa, Germany and South Korea, there is not much of a difference between any two of the three groups, whether one compares actives with inactives, actives with “nones,” actives with the two latter groups combined, or inactives with the unaffiliated.

The U.S., however, is a notable exception as the only country in which the actively religious are more likely than the unaffiliated – by a statistically significant margin – to say they are in very good health: 32% of actively religious Americans say they are in very good health, compared with 25% of the unaffiliated. A similar share of inactives (27%) say they are in very good health, but from a statistical standpoint, this figure does not differ significantly from either of the others.

Actively religious Americans are more likely than the unaffiliated to report very good health even after advanced statistical analysis controlling for age, education and other demographic factors. This positive relationship between religious participation and self-rated health in the U.S. is often – but not always – found in other nationally representative survey datasets. (For more about variations in U.S. self-rated health data results, see this sidebar.)

What is self-rated health?

The measure of overall health in this report comes from the World Values Survey, which asked respondents: “All in all, how would you describe your state of health these days?” Survey-takers can respond, “very good,” “good,” “fair” or “poor.”

Asking people to assess their own health may seem like an imperfect method, but past research has shown that self-rated health responses are generally reliable proxies for overall physical well-being. In fact, according to one study, responses to this seemingly simple question can be used to accurately predict physical fitness, the number of times someone will visit the doctor in the coming year, and overall longevity.

Of course, people lack complete knowledge of their bodies and may consider themselves to be healthy even when hidden dangers, such as early-stage cancer or high blood pressure, go unnoticed and untreated. Nevertheless, on average, people’s self-assessments of their own health seem to be valid and reliable summaries of overall health.

In most of the remaining 25 countries, there are no statistically significant differences between the actively religious and the unaffiliated. Where there is a gap, the actively religious are less likely to say they are in very good health. And comparisons between the actively religious and the inactives are murky: In 17 countries out of 25, there is not much of a difference between the two groups, while in four countries actives are more likely to report better health, and in four countries the inactives are healthier. (For detailed tables showing all countries, see Appendix B.)

When comparing the actively religious to a combined population of inactives and the unaffiliated outside of the U.S., actives are healthier only in Taiwan, while the opposite is true in five countries: Slovenia, Estonia, Chile, Ecuador and Spain.

However, these differences are mostly erased after taking into account age and other demographic characteristics. Actively religious people tend to be older, and therefore more vulnerable to the diseases and injuries that disproportionately affect older adults. When controlling for age and other factors, actively religious people in 23 out of the 25 countries are about as likely as others to say they are in very good health. (For the details of this analysis, see here.) In the remaining two countries – Mexico and Taiwan – actives are more likely than others to say they are in very good health, as is also true in the U.S.

Religion’s links to health in the U.S. are not always clear

Although the data presented in this report suggest that Americans who regularly attend worship services are more likely to say they are in better health – and academic studies often find links between religious activity and, say, stress or longevity – the connection between overall self-rated health and religion in the U.S. does not always show up in national surveys.

Although the data presented in this report suggest that Americans who regularly attend worship services are more likely to say they are in better health – and academic studies often find links between religious activity and, say, stress or longevity – the connection between overall self-rated health and religion in the U.S. does not always show up in national surveys.

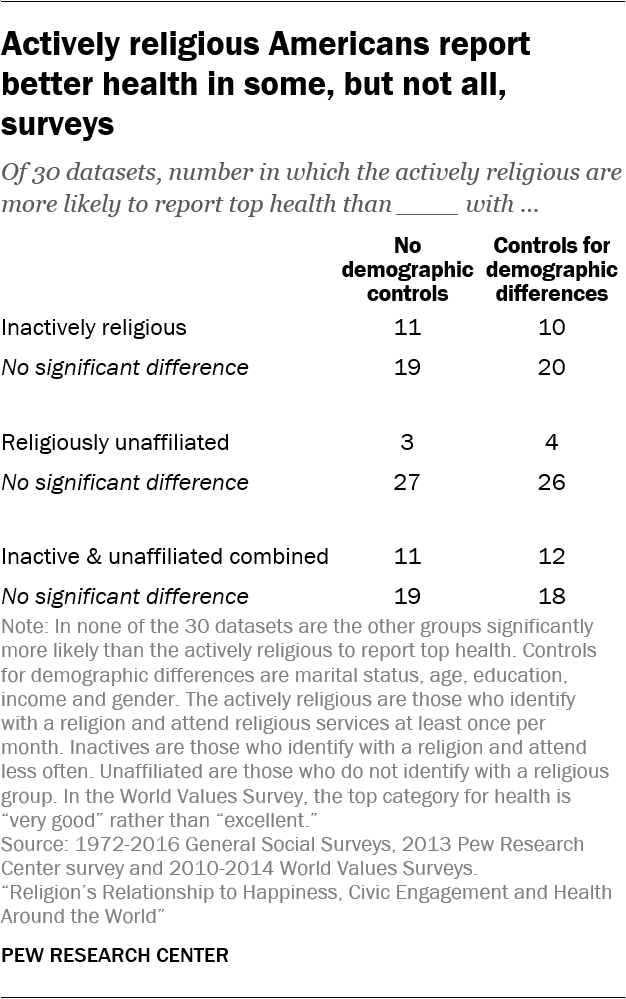

A Pew Research Center analysis of nationally representative datasets finds that in most surveys, there is no significant difference among actively religious Americans, the inactively religious and the unaffiliated in the share who choose the most positive option provided to describe their health (“very good” or “excellent,” depending on the survey).22 In fact, whether the actively religious are statistically distinct depends on who they are compared against, how self-rated health is measured and which datasets are used.

In preparing this report, Pew Research Center examined the relationship between religion and self-rated health in 30 U.S. datasets, including the 2011 World Values Survey, 28 waves of the General Social Survey conducted between 1972 and 2016 and a 2013 Pew Research Center survey on radical life extension. Cross-national analysis of self-rated health in this report is based on WVS data because it provides a comparable measure across a wide number of countries.

The U.S. results are muddy, with some datasets surfacing statistically significant relationships and others showing no connection between religion and self-rated health. However, when statistically significant evidence on the link between religion and health is found, it always reveals a positive association. In other words, there is no dataset in which the actively religious are significantly less likely to report top health than the inactively religious, the unaffiliated or both of the latter groups combined.

In 11 of the 30 datasets, when comparing the actively religious against a combined population of inactive and unaffiliated Americans, actively religious Americans are more likely to report top levels of health than all other Americans.23

When dividing the population into three groups of religious engagement instead of just two, a more nuanced picture emerges: The actively religious are more likely than the inactive to report top health in 11 of the 30 datasets and more likely than the unaffiliated to do so in just three of the 30 datasets.24 While it may seem insignificant that the active are more likely to report top health than “nones” in just 10% of datasets, it is striking that the unaffiliated never topped the actively religious, despite apparent demographic advantages. Since the demographic composition of each of these groups varies in ways that might affect health – “nones,” for example, tend to be younger, and therefore would be expected to be healthier if everything else were equal – all comparisons were repeated after controlling for demographic characteristics such as gender and age. The patterns were largely the same.25

These results indicate that the relationship between active religion and self-rated health is not strong enough to consistently emerge across these U.S. surveys.26 However, the fact there is a significant positive relationship in some surveys, and never a negative relationship, suggests a tendency for actively religious Americans to rate their own health more positively than their compatriots.

Drinking, smoking, exercise and obesity

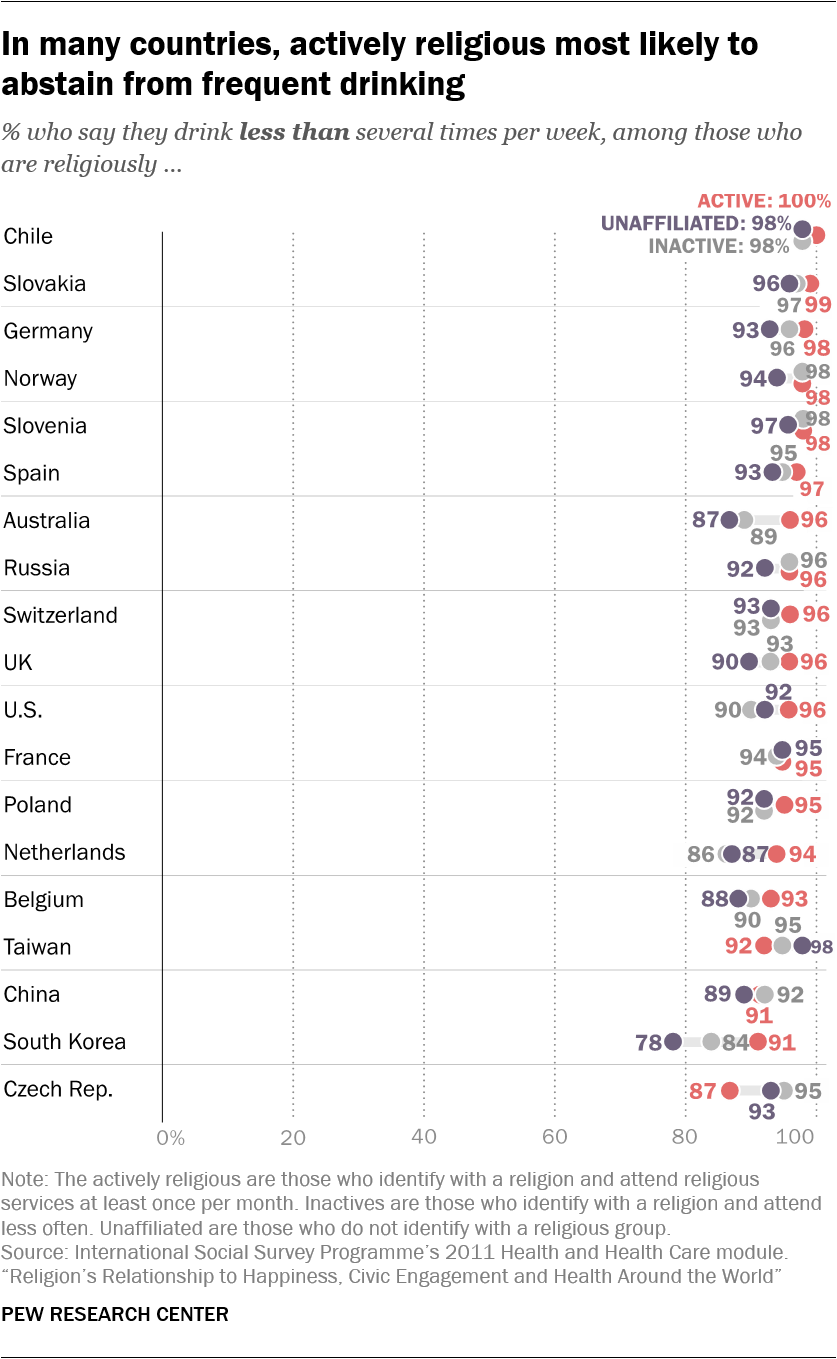

By four other measures related to health, results are mixed. The International Social Survey Programme’s 2011 Health and Health Care module asked respondents how often they smoke, drink alcohol and exercise, and it also collected height and weight data, from which Pew Research Center analysts calculated body mass index (BMI). While actively religious people in many countries are less likely than others to say they drink frequently or ever smoke, they are not more likely to exercise regularly or to have a BMI of less than 30.27

By four other measures related to health, results are mixed. The International Social Survey Programme’s 2011 Health and Health Care module asked respondents how often they smoke, drink alcohol and exercise, and it also collected height and weight data, from which Pew Research Center analysts calculated body mass index (BMI). While actively religious people in many countries are less likely than others to say they drink frequently or ever smoke, they are not more likely to exercise regularly or to have a BMI of less than 30.27

In nine out of 19 countries with available data, including the U.S., UK and Australia, actively religious people are less likely than the unaffiliated to say they drink several times per week.28 In nine countries, there is no statistically significant difference between the groups. Actives are also less likely than inactives to say they drink several times a week in nine countries, and again, there is no significant difference in nine countries. Only in Taiwan are actives more likely than the unaffiliated to drink frequently, and only in the Czech Republic are actives more likely than inactives to drink several times a week.

In 15 out of 19 countries, there is no statistically significant difference on this measure between inactives and “nones.” When these two groups are combined for comparison with the actively religious, actives are less likely than everyone else to drink frequently in 11 out of 19 countries, while the opposite is not true anywhere. But other factors (beyond religious participation) partially explain this pattern: Statistical models controlling for gender and other demographic characteristics show that actively religious people drink less in eight countries, while they drink more only in the Czech Republic (see here).

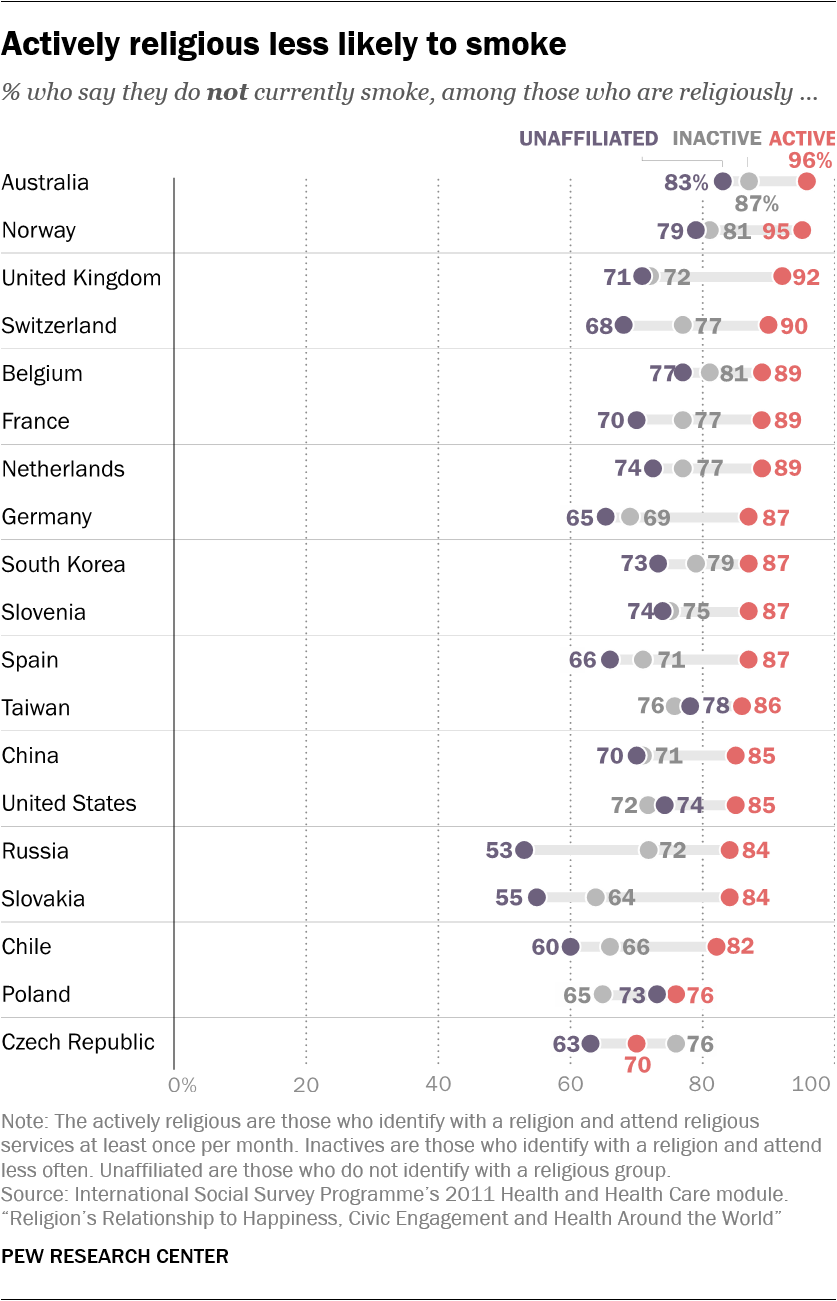

Religion’s link to health is clearer when it comes to smoking: Actively religious adults are less likely than the unaffiliated to say they ever smoke in 17 out of 19 countries, including the U.S., Russia and Germany. In the remaining two countries (Poland and the Czech Republic) the differences are not statistically significant. Actives are also less likely than inactives to smoke in 18 out of 19 countries; the Czech Republic, which has an unaffiliated majority, is the only country where the difference is not statistically significant.

Religion’s link to health is clearer when it comes to smoking: Actively religious adults are less likely than the unaffiliated to say they ever smoke in 17 out of 19 countries, including the U.S., Russia and Germany. In the remaining two countries (Poland and the Czech Republic) the differences are not statistically significant. Actives are also less likely than inactives to smoke in 18 out of 19 countries; the Czech Republic, which has an unaffiliated majority, is the only country where the difference is not statistically significant.

While smoking and drinking are two important measures of healthy behavior, there are many others – including some that do not seem positively connected to religious engagement. Take, for instance, exercise – a behavior doctors overwhelmingly recommend as part of a healthy lifestyle.

While smoking and drinking are two important measures of healthy behavior, there are many others – including some that do not seem positively connected to religious engagement. Take, for instance, exercise – a behavior doctors overwhelmingly recommend as part of a healthy lifestyle.

If anything, people who are not actively religious are more likely to say they exercise several times per week. Actives are less likely than the unaffiliated to exercise in five out of 19 countries, including Poland, Slovenia and Switzerland. Only in South Korea are actives more likely to exercise than “nones,” while in the remaining 13 countries, including the U.S., differences are not significant. Comparing actives with inactives produces a difference in only one of the 19 countries, Spain, where inactives are more likely to exercise several times a week.

The picture is similar when examining obesity (body mass index calculated to be 30 or higher based on reported height and weight).29 Actively religious people are more likely than the unaffiliated to be obese in five out of 19 countries (the Czech Republic, Poland, Switzerland, Spain and France), while in the remaining 14 countries, including the U.S., the differences are not statistically significant.

The picture is similar when examining obesity (body mass index calculated to be 30 or higher based on reported height and weight).29 Actively religious people are more likely than the unaffiliated to be obese in five out of 19 countries (the Czech Republic, Poland, Switzerland, Spain and France), while in the remaining 14 countries, including the U.S., the differences are not statistically significant.

However, the U.S. stands out as an exception when comparing the obesity of the actively religious and the inactively religious: Religiously active Americans are less likely to have a BMI of at least 30 than are those who are affiliated but inactive. In Chile, on the other hand, actives are more likely than inactives to be obese, while in the remaining 17 countries, there is no significant gap.

Overall, there is a mixed relationship between religion and health. While the actively religious are less likely to smoke and drink in some countries, they are not healthier when it comes to exercise and weight. And on average, across more than two dozen countries, actively religious adults are not more likely to report being in very good health.

Religion and health – a complicated history

The relationship between religion and health has occupied researchers for over a century. In 1897, the sociologist Émile Durkheim argued that a nation’s suicide rate was largely dependent on the religious practices of its population and posited that Protestants, for example, suffered greater emotional health problems than Catholics because Protestantism did not promote adequate levels of social integration.30

In the decades that followed, the potentially harmful effects of religion were brought to the public’s attention, in part due to the popular writings of secular intellectuals including Sigmund Freud and Friedrich Nietzsche. Freud, in his 1927 book “Future of an Illusion,” compared religion to a childhood neurosis, while Nietzsche famously described Christianity as a “sickness.”31 Even in the second half of the 20th century, some influential psychologists continued to follow Freud’s lead by defining religion as a neurosis that should be cured by psychotherapy.32

Recently, scholars have applied more scientific rigor to their research on religion, and many of the studies that have been published in the past 30 years have found that religious people tend to live longer, get sick less often and are better able to cope with stress.33 One study of adults in Texas, for example, found that regular service attendance is positively associated with a variety of healthy behaviors such as doctor visits, taking vitamins, and refraining from unhealthy behaviors such as alcohol and tobacco use.34 Another paper concluded that people whose obituaries referenced religion tended to have lived longer than those whose obituaries made no mention of religion.35

In the comprehensive “Handbook of Religion and Health,” Duke University professor Harold G. Koenig and co-authors summarize 21st-century findings from the rapidly expanding field of religion and health research. According to their analysis, religion is positively associated with life satisfaction, happiness and morale in 175 of 224 studies (78%). Furthermore, religion is positively associated with self-rated health in 27 of 48 studies (56%), with lower rates of coronary heart disease in 12 of 19 studies (63%) and with fewer signs of psychoticism (“characterized by risk taking and lack of responsibility”) in 16 of 19 studies (84%).36

Of course, this also means that a substantial number of studies have found no clear association, or have even concluded that religion is associated with worse health outcomes. For example, several studies have found that religious people tend to have a higher body mass index (BMI).37 Northwestern University cardiologist Matthew Feinstein and his colleagues, in an analysis of an unusually large sample of 5,500 Americans, concluded that both religious service attendance and regular spiritual experiences are associated with higher rates of obesity.38 Other studies suggest that people who view humans as sinful and participate in religious communities that emphasize human sinfulness are more likely to suffer from anxiety and depression.39

And, just as some religions seem to contribute to positive health outcomes because they discourage alcohol and tobacco consumption, other religions may lead to poor physical health outcomes due to certain behavioral proscriptions. For example, Jehovah’s Witnesses oppose blood transfusions, and some religious groups, including certain Amish and Orthodox Jewish communities, discourage immunizations, as Koenig and his colleagues point out.

Regardless of the specific outcomes reported by the many studies on this topic, it is worth noting that many attempts to link health and religion result in null findings, and that the research often has serious methodological limitations. Since most of the studies have been conducted in the U.S., Canada and Western Europe, it is difficult to reach sweeping conclusions about the impact of religion on health on a truly global level.40

In addition, much of the research available relies on small samples – and research with larger numbers of respondents often uses samples that are not representative of the broader population.41 This includes studies of only older adults, only women or men, clergy, members of specific denominations, or people in specific regions of a nation.42 There also has been a disproportionate focus on mental health; far fewer research projects have looked at the relationship between religion and physical health.

Perhaps most importantly, most of this research (including this cross-national study) has used data collected at a single point in time (rather than longitudinal data).43 Associations between religion and health based on cross-sectional research may represent the effects of religion on health – or the effects of health on religion. When people find themselves suddenly ill, for instance, they may adopt a habit of regular prayer even if they were not previously religious. Some research indicates that this kind of “crisis religiosity” can produce a statistical association between poor health and prayer.44

Indeed, the reliance on cross-sectional data limits researchers’ ability to speak definitively to the causal effects of religion on health and well-being. For example, physical barriers may prevent some sick people from participating in formal religious activities such as service attendance.45 If sick people cannot make it to church, then church attenders appear to be relatively healthy when looking only at cross-sectional data. Similarly, some research points to reverse causal effects when it comes to the association between religion and mental health. For instance, people who have depressive episodes are relatively likely to scale back their religious participation, which could mistakenly suggest a positive association between religion and mental health46

Consequently, even when research does establish a positive association between religion and health, it is not clear that religion causes the beneficial health outcome.

Infrequent attenders and ‘nones’ differ modestly on some measures

The findings in this report suggest that regular religious participation is tied to individual and societal well-being – that is, people who have a religious affiliation and attend worship services at least once a month tend to fare better on some (but not all) measures of happiness, health and civic participation. As a result, this report has mainly focused on differences between actively religious people and others.

The findings in this report suggest that regular religious participation is tied to individual and societal well-being – that is, people who have a religious affiliation and attend worship services at least once a month tend to fare better on some (but not all) measures of happiness, health and civic participation. As a result, this report has mainly focused on differences between actively religious people and others.

Yet in 28 of the 35 countries studied across datasets analyzed in this report, the actively religious are a minority of the adult population: Especially in Europe, but also in some countries in the Asia-Pacific region, levels of affiliation are declining and regular attendance at religious services is relatively rare. In many economically advanced countries, the share of “nones” has been rapidly increasing, while the share of inactively religious people has declined.47

How will societies change in the future if the inactively religious share of the population continues to shrink and the religiously unaffiliated percentage grows? The answer is uncertain for many reasons, including the possibility that the beliefs and behaviors of people in these groups may change. But there could be clues in the current data, which suggest that any differences between religiously inactive and unaffiliated people on key measures of well-being are relatively modest.

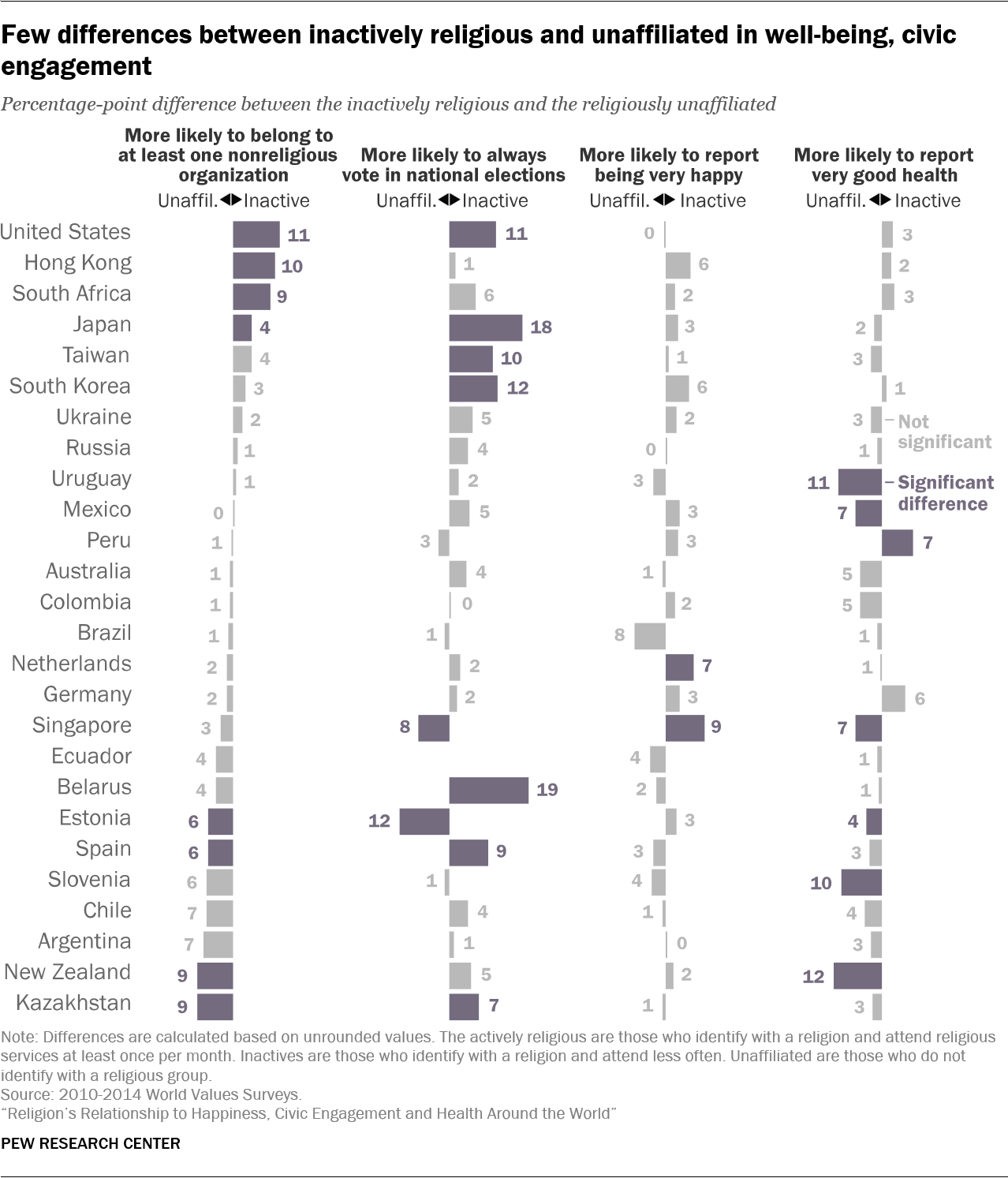

For example, in 24 out of 26 countries analyzed, inactives and the unaffiliated are about equally likely to describe themselves as “very happy.” Likewise, the drinking habits of inactives and the unaffiliated are similar in 15 out of 19 countries. These patterns remain intact after adjusting for demographic characteristics such as age, gender and education.

There is also little difference in overall self-rated health between inactively religious and unaffiliated people in 19 of 26 countries. Although “nones” report better self-rated health in six countries, these gaps mostly disappear after the data are adjusted for demographic characteristics such as age and gender. After controls, New Zealand and Uruguay are the only countries in which “nones” are more likely than inactives to report very good health, while inactives come out ahead on this measure only in Peru.

Again, there are no broad patterns favoring the inactively religious or the unaffiliated when it comes to civic engagement. Before controls, the inactively religious are more likely than “nones” to participate in voluntary (nonreligious) organizations in four of 26 countries, while the opposite is true in four countries. After controls, the inactively religious are more likely to join a group in four places (Hong Kong, Japan, South Africa and the United States), while the same is true for the unaffiliated in two countries (Estonia and Kazakhstan).48

Inactives do tend to have healthier smoking habits: They are less likely than “nones” to smoke in seven of 19 countries before taking demographic traits into account. In the remaining countries, there is no difference between the groups.49

At the same time, “nones” sometimes seem slightly healthier on the measures of obesity and exercise. “Nones” are less likely to be obese in seven of 19 countries, including the U.S., while in the remaining countries, there is no significant difference. (After demographic controls, “nones” are less likely than the inactively religious to be obese in four countries: Australia, the Netherlands, Switzerland and the United States.) “Nones” are also more likely to exercise frequently in three of 19 countries, while in the remaining countries, differences between the two groups are not significant.50

Overall, the results of this analysis suggest that the differences between the inactively religious and the unaffiliated fit less of a clear pattern than the differences between the actively religious and everyone else. When there are well-being differences between the actively religious and all others, they almost always favor the actively religious; gaps between the inactively religious and the unaffiliated are more modest, and sometimes go in both directions. Therefore, it may be that the future size of actively religious populations will be more consequential for the outcomes considered in this report, and that the relative shares of the inactively religious and the unaffiliated in the remaining population will matter less.

What are the relationships between religion and well-being after considering factors such as age, gender, marital status, income and education?

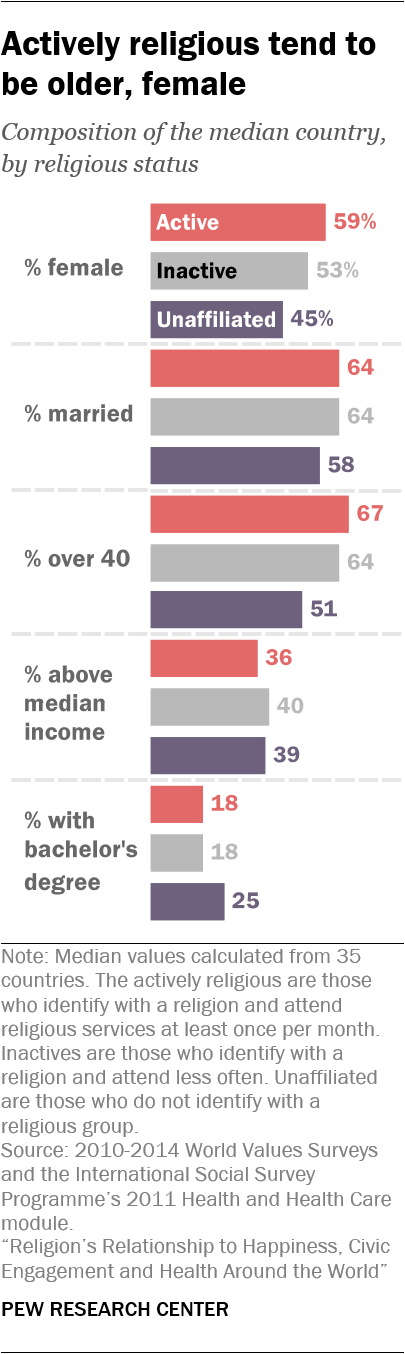

Compared with their less religious counterparts, the actively religious tend to be older, slightly less educated, and more likely to be female and married. Such differences raise the question: Are people happier, more civically engaged, or less likely to smoke and drink because of their religious activity, or because of these other demographic traits?

Compared with their less religious counterparts, the actively religious tend to be older, slightly less educated, and more likely to be female and married. Such differences raise the question: Are people happier, more civically engaged, or less likely to smoke and drink because of their religious activity, or because of these other demographic traits?

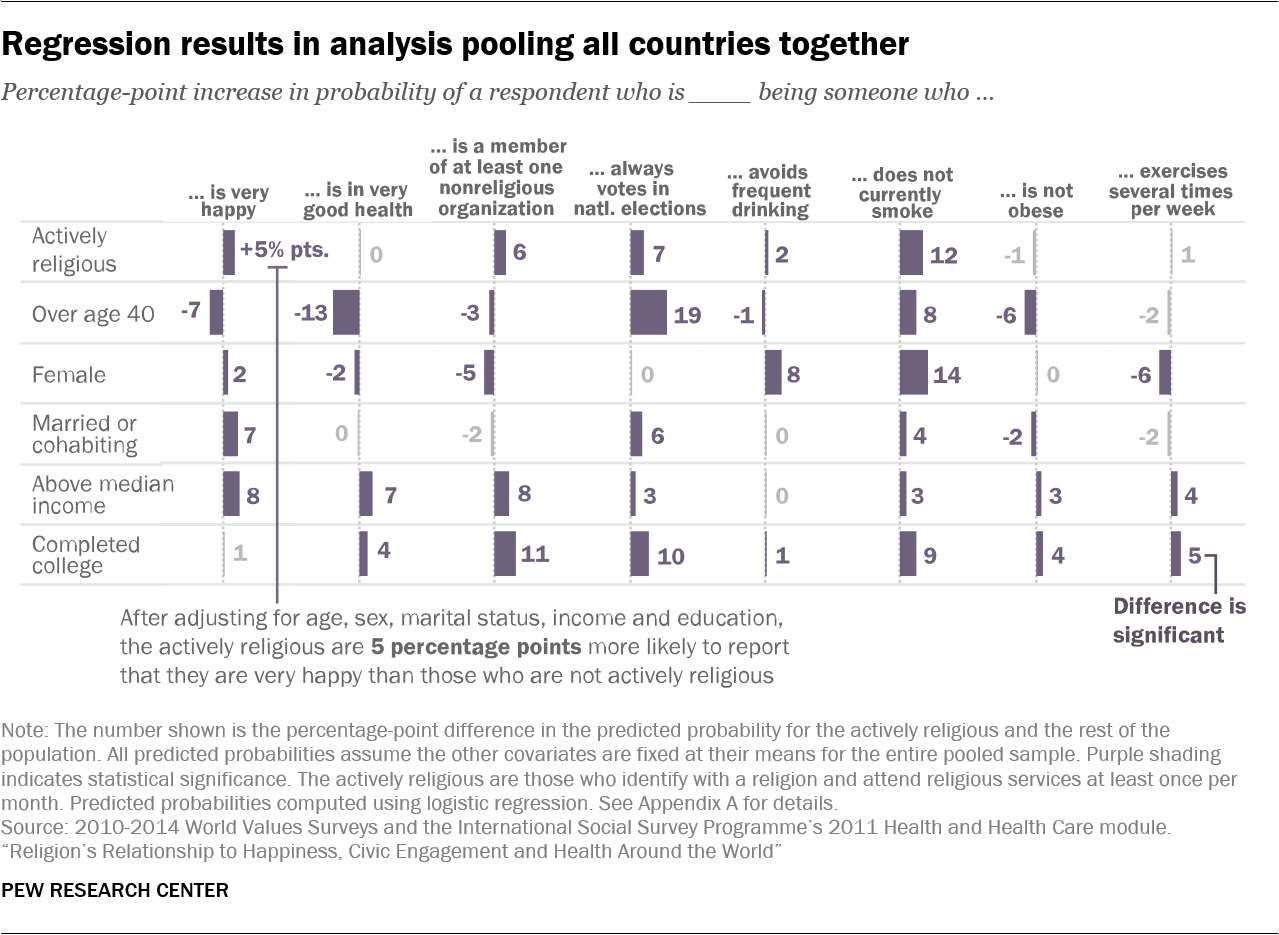

To test for the independent effect of religion, Pew Research Center analysts constructed statistical models that evaluate the association of religious activity with eight measures of individual and societal well-being after controlling for age, gender, education, income and marital status (see Methodology for details).

The table below shows the predicted effects of each factor in a pooled analysis of all countries in the datasets (26 countries for the World Values Survey measures and 19 countries for the items measured in the ISSP).51 In general, across all the countries analyzed, being actively religious is associated with a greater likelihood of being very happy, belonging to a nonreligious organization, always voting, drinking infrequently and not smoking. In this pooled analysis, the actively religious are not more likely to report very good health, nor do they have better outcomes with regard to obesity and exercise. These findings are broadly in line with results presented earlier in the report.

That said, other demographic factors also have close links to well-being. For example, in the regression analysis, being over 40 reduces the chance that one will report being very happy or in very good health and increases the likelihood of always voting. Men are more likely to be smokers and drinkers. Having above-median income and being married or cohabiting are associated with greater happiness. Completing college increases the chance of belonging to a nonreligious organization and always voting.

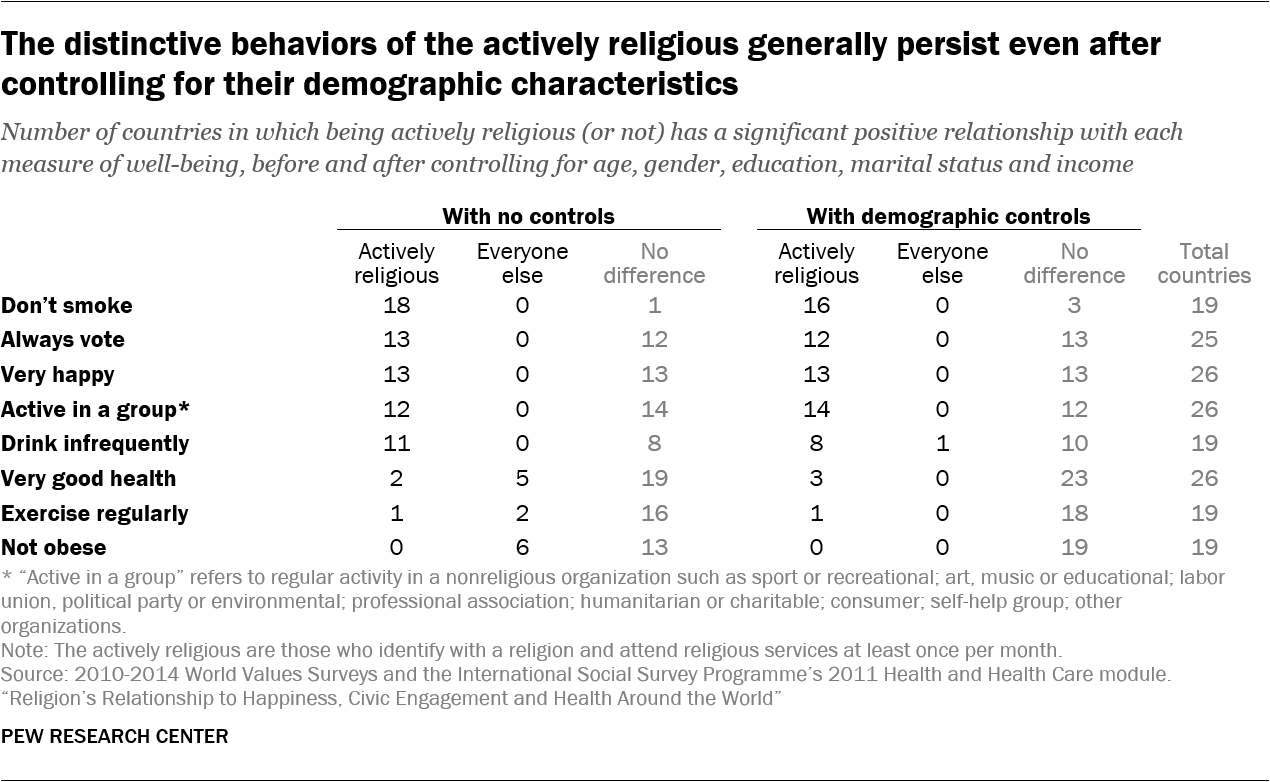

Pew Research Center analysts also compared the number of countries in which being actively religious is tied to well-being advantages, both before and after introducing demographic controls (see Appendix C for regression results for each country).

Generally speaking, the country-level patterns shown earlier in this report that connect religious activity and well-being persist after controlling for demographic factors, particularly when it comes to the measures of happiness and civic participation. In 13 out of 26 countries, both before and after controls, the actively religious are happier than everyone else (that is, the combined population of the inactively religious and the unaffiliated). In the remaining countries, there is not much of a difference between the two groups.

Similarly, whenever there is a difference on voting, the actively religious vote more often – in 13 countries prior to controls and 12 countries after controls. And after factoring in the demographic characteristics of each group, the number of countries in which the actively religious are more likely to join voluntary groups rises from 12 to 14.

The smoking pattern also remains similar: Before controls, the actively religious are less likely than everyone else to smoke in 18 out of 19 countries; after controls, the outcome remains statistically significant in 16 of the 19 countries. And in almost all the countries analyzed, there is no connection between religious participation and frequency of exercise whether demographic characteristics are taken into account or not.

The links between religion and self-rated health, obesity and drinking, however, do seem more dependent on demographic factors, such as age and gender.

The advantage less-religious people sometimes have on measures of self-rated health and obesity in the unadjusted analysis is erased when the demographic traits of each group are considered. For instance, with no controls, the actively religious are less likely than everyone else to report very good health in five countries (Spain, Ecuador, Chile, Estonia and Slovenia), and only more likely to do so in two countries (the U.S. and Taiwan). After taking into account the compositional characteristics of each group, however, no countries remain in which the actively religious are less likely to be very healthy, and a third country in which religious participation is associated with better health emerges (Mexico).

By the same token, before controls, the actively religious are more likely to be obese in six countries (the Czech Republic, Chile, Slovakia, Switzerland, Poland and France). But this relationship is eliminated after controlling for demographic factors.

Meanwhile, the healthier drinking behaviors of actively religious people are not as pronounced when controlling for other factors: The number of countries in which the actively religious are significantly less likely to drink frequently drops from 11 before controls to eight after controls. In one country, the Czech Republic, actives are more likely to drink frequently when controlling for demographic factors.

While results from the regression analysis do not perfectly mirror the unadjusted findings, they bolster the conclusion that when there are differences between groups, they tend to favor religiously active people. On some outcomes, such as happiness, civic participation and smoking, these positive links appear in a similar number of countries both before and after taking into account personal characteristics. On other measures, such as self-rated health and obesity, “everyone else” initially seems at an advantage, but once the data are adjusted for demographic characteristics, this advantage fades away.