If you are an avid social media user — and have been following recent events in Ferguson, Missouri — you may have noticed a difference in the content of your Facebook and Twitter feeds on the story. The reason goes back to a complex and somewhat mysterious interplay between the platforms’ designs and your own behavior.

A number of journalists and commentators observed a jarring disconnect between the mostly uncontroversial posts on Facebook (like chatter about celebrities taking the Ice Bucket Challenge to raise funds for the fight against Lou Gehrig’s disease), and the stream of visceral reportage from the tense scene in Ferguson, where citizens had gathered to protest the August 9th police killing of an unarmed black teen, Michael Brown.

A number of journalists and commentators observed a jarring disconnect between the mostly uncontroversial posts on Facebook (like chatter about celebrities taking the Ice Bucket Challenge to raise funds for the fight against Lou Gehrig’s disease), and the stream of visceral reportage from the tense scene in Ferguson, where citizens had gathered to protest the August 9th police killing of an unarmed black teen, Michael Brown.

Some, like sociologist Zeynep Tufekci, noticed a delayed reaction to the breaking news on Facebook. Others, like Gigaom’s Mathew Ingram, attributed the lack of news on Facebook to the way that interactions are structured on the social network. They and others argued that Facebook’s algorithmic filtering heavily influences the content Facebook users see on the site, and why their newsfeeds haven’t been flooded with images and stories about tear gas, demonstrations and arrests.

We know that the algorithms influence what content we are exposed to on Facebook and on other internet platforms. But we don’t have a precise understanding of how different kinds of behavior influence the algorithm.

One aspect of Facebook culture that may minimize news exposure is simply that people prefer to do other things on the site. Yes, around half of Facebook users (47%) say they get news there — a similar proportion to that of the Twitter population. But most users aren’t going there for news, but to enjoy the social network as a way of keeping up with friends and family. Deeper engagement with this kind of social content reinforces Facebook’s filtering — but we don’t know exactly how much.

Second, the kind and amount of news that social media users see on these platforms may depend in part on who they choose to connect with there (though the level of engagement with those sources also influences whether they appear in one’s newsfeed, too).

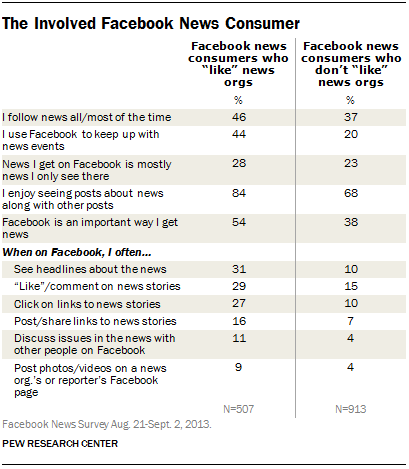

Only a third (34%) of Facebook users who ever get news on that site “like” or follow journalists or news organizations. But among those who do, fully 48% say that most of the news they get on Facebook comes from those sources. Among the users who “like” news organizations, 31% say that they “often” see news headlines in their feed. That number drops to just 10% among those who do not.

While analogous data for Twitter usage are not yet available, a 2012 Pew Research survey provides some clues. Among Twitter news followers, 27% said they get most of their news links from news organizations or journalists, compared with 13% among Facebook news followers.

Ultimately, a social network full of journalists will probably result in a different picture of the world than one full of friends and family. But there is still much that the public research community does not know about how these different variables work together. Given the kind of differences that occurred on the Ferguson story, the implications are highest for those who identify a service like Facebook as their primary news source if the measure is the delivery of hard news. The data suggest that this describes a tiny portion of the U.S. population. But that could change as younger generations — at home on the social web — engage with the outside world through these kinds of networks.