The online health community and the media lit up this week in a debate over whether it’s tasteful, appropriate or even beneficial to discuss one’s health problems with the world on social media.

While there’s been some discussion of the topic before, the news this week involved two prominent journalists who raised questions about one woman’s public approach to her life with stage IV breast cancer. Lisa Bonchek Adams, a 44-year-old mother of three, has lived with cancer for six years and developed a following among others diagnosed with cancer as well as clinicians, journalists and people who simply appreciate her perspectives.

Her tweets and blog posts address topics such as her approach to talking to her kids about her illness, her medical treatments and thoughts about facing the end of life. The Guardian’s Emma Keller wrote a column stating that “Adams was dying out loud.” A few days later, The New York Times’ Bill Keller (who is Emma’s husband) wrote a column relating his father-in-law’s “calm death” from cancer and asked whether Adams’ public updates about her health are the right approach.

We’ll leave the taste debate aside and instead look at the data about how many Americans gather and share health information online and whether there are any known benefits to doing so.

The Pew Research Center has studied the social life of health information since 2000 when we first measured how many people use online resources to find information or connect with others about health conditions.

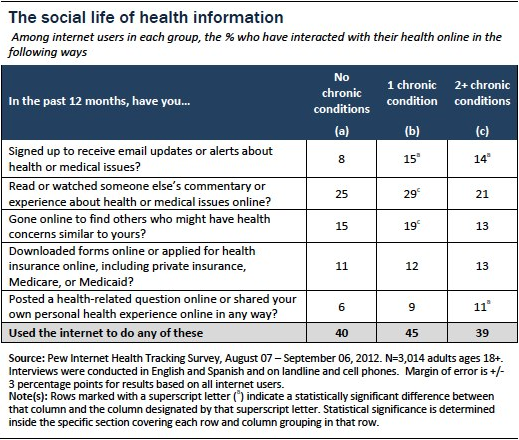

Our latest national survey on the topic finds that seven-in-ten (72%) adult internet users say they have searched online for information about a range of health issues, the most popular being specific diseases and treatments. One-in-four (26%) adult internet users say they have read or watched someone else’s health experience about health or medical issues in the past 12 months. And 16% of adult internet users in the U.S. have gone online in the past 12 months to find others who share the same health concerns.

Caregivers and those living with chronic conditions, such as diabetes, heart disease and cancer, are more likely than other internet users to do all of these things. Clinicians are still the top source of health information in the U.S., according to the same survey, but online information, curated by peers, is a significant supplement.

The small group of people who use the internet and other online tools to connect with others are highly engaged. Of the 8% of internet users who say they have posted a health-related question or comment online within the past year, four-in-10 said they were sharing their personal health experience.

Our research shows that patients and caregivers have critical health information — about themselves, about each other, about treatments — and they want to share what they know to help other people. Technology helps to surface and organize that knowledge to make it useful for as many people as possible.

Some observers may think it is odd, but this online sharing could be the modern version of an age-old instinct to seek solace among peers. As Thomas Jefferson wrote in 1786, “Who then can so softly bind up the wound of another as he who has felt the same wound himself?”

Indeed, many clinicians recommend group support as part of a treatment plan for a wide range of issues, from weight loss to the management of chronic and life-changing diagnoses, such as cancer. Academic publication is a slow process, however, and the internet is evolving quickly, so there are relatively few studies measuring the effectiveness of social media.

However, Twitter, Facebook, blogs, and other platforms seem uniquely suited to adapt to the changing needs of people living with chronic health conditions, particularly as patients move from the shock of a new diagnosis to long-term management. This is particularly true for people facing a rare disease diagnosis. A new research paper released earlier this month studied parents of children with rare chronic diseases and found that social media in particular provided an effective support network. This echoes our own findings and adds to the pile of evidence showing the psychosocial benefits of connecting online.

As one mother whose son has Canavan disease wrote in a book about rare-disease caregivers: “Before the internet, we were alone. In 1996, when Jacob was born, there was no search engine to offer me any information. Today, because of social media, we are connected with many people who are fighting the same fight as we are. The internet has made our small disease larger and we are able to educate many more people now.”

PatientsLikeMe, a health data-sharing platform, is one leader in the new field of using the internet to help patients, caregivers and researchers connect online. One study, published in Epilepsy & Behavior, showed that, prior to using the site, one-third of respondents (30%) did not know anyone else with epilepsy with whom they could talk. Now, two-thirds (63%) of those people had at least one other person with whom they could consult to gain a better understanding of seizures and learn about symptoms or treatments. Another study, published in the Journal of Medical Internet Research, found that 41% of HIV patients who use the site said they had reduced their own risky behaviors thanks to online support and education.

Smoking cessation is another example of a health intervention that works well when people support each other online. Members of an online support group like QuitNet stick around to help newcomers because they want to give back what they received when they were starting out.

In the end, this episode illustrates the confluence of two powerful forces:

- an ancient instinct to seek and share advice about health

- a newfound ability to do so at internet speed and at internet scale.

It may not be for everyone, but our research shows that the social life of health information is a durable trend.