A 13-year-old California girl is at the center of the latest national debate about end-of-life care. Jahi McMath was pronounced brain-dead in December following complications related to a tonsillectomy to treat sleep apnea. A legal battle between McMath’s family and Children’s Hospital Oakland ensued, forcing the hospital to keep the girl on a ventilator. On Sunday, citing a court order, the hospital released McMath to her family (via the Alameda County coroner).

In another case, in Texas, Marlise Machado Muñoz collapsed in November and now has no brain activity. Her husband wants her taken off life support, citing her wishes, but Muñoz was 14 weeks pregnant when she collapsed and Texas law requires expectant mothers to be kept alive.

The two situations highlight the complicated nature of end-of-life questions. A recent Pew Research Center survey explores Americans’ views on the topic, ranging from the morality of suicide to personal preferences for end-of-life care. Here are some of the key findings:

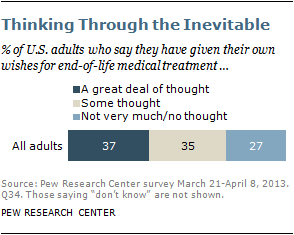

11  Death may not be the most comfortable topic to ponder, but 37% of Americans say they have given a great deal of thought to their own wishes for end-of-life medical treatment – up from 28% in 1990. A third (35%) say they have put their wishes in writing. At the same time, however, about a quarter (27%) say they’ve given no thought or not very much thought to their wishes.

Death may not be the most comfortable topic to ponder, but 37% of Americans say they have given a great deal of thought to their own wishes for end-of-life medical treatment – up from 28% in 1990. A third (35%) say they have put their wishes in writing. At the same time, however, about a quarter (27%) say they’ve given no thought or not very much thought to their wishes.

22 While a clear majority (66%) of U.S. adults say that there are sometimes circumstances in which doctors and nurses should allow a patient to die, nearly a third (31%) say medical professionals always should do everything possible to save a patient – twice as many as expressed this view in 1990 (15%).

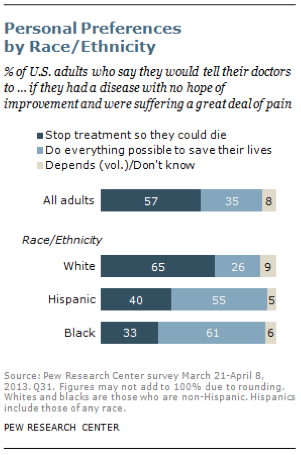

33  There are substantial differences across racial and ethnic groups when it comes to personal choices about end-of-life medical treatment. Nearly two-thirds of whites (65%) say they would stop their medical treatment if they had an incurable disease and were suffering a great deal of pain; by contrast, 61% of blacks and 55% of Hispanics say they would tell their doctors to do everything possible to save their lives in these circumstances. According to interviews by Religion News Service, possible reasons for these differences include historic experiences, religious faith and family roles.

There are substantial differences across racial and ethnic groups when it comes to personal choices about end-of-life medical treatment. Nearly two-thirds of whites (65%) say they would stop their medical treatment if they had an incurable disease and were suffering a great deal of pain; by contrast, 61% of blacks and 55% of Hispanics say they would tell their doctors to do everything possible to save their lives in these circumstances. According to interviews by Religion News Service, possible reasons for these differences include historic experiences, religious faith and family roles.

44 The public is closely divided on physician-assisted suicide, with 47% in favor of laws that would allow doctor-assisted suicide for terminally ill patients and 49% opposed, largely the same as in a 2005 Pew Research survey. Americans’ views on whether a person has a moral right to suicide vary based on that person’s circumstances.

55 Four states currently allow physician-assisted suicide. From when Oregon’s Death With Dignity Act went into effect in late 1997 through the end of 2012, 673 patients died from lethal medications prescribed under the law in that state. Washington has had a similar law since early 2009; through the end of 2012, at least 240 people there have died from lethal medications. (More than 100 other Death with Dignity Act participants in Washington died without taking the medication.) In December 2009, the Montana Supreme Court ruled that there was nothing in state law preventing physician-assisted suicide for the terminally ill, but state officials do not keep track of such deaths. Since Vermont legalized physician-assisted suicide in May, one citizen has taken advantage of the law, according to the state’s health department.