While several organizations have long tracked the risks faced by professional journalists working in harm’s way, until recently, less attention has been paid to the occupational hazards faced by “citizen journalists” and “netizens.” These newer members of the media document some of the most dangerous conflicts, sometimes in places that are off-limits to professional journalists. New figures show that the war in Syria, in particular, has taken a heavy toll among them.

While several organizations have long tracked the risks faced by professional journalists working in harm’s way, until recently, less attention has been paid to the occupational hazards faced by “citizen journalists” and “netizens.” These newer members of the media document some of the most dangerous conflicts, sometimes in places that are off-limits to professional journalists. New figures show that the war in Syria, in particular, has taken a heavy toll among them.

After the onset of the Arab Spring in late 2010, Reporters sans frontieres (Reporters Without Borders/RSF)—one of the principal organizations that monitors attacks on freedom of information worldwide— began tracking this new category of journalists. RSF defined citizen-journalists as those who have had no professional media training, did not work in journalism before and who only started working to document a conflict once it began. They may be working freelance to sell their pictures and stories, or they may have set up an affiliation with a local media center.

Netizens share a similar background to citizen-journalists, but they focus on the use of internet tools to disseminate their work. While RSF states that many of the citizen journalists and netizens in Syria may be sympathetic to the forces trying to overthrow the government of President Bashar al-Assad, the organization says they are not combatants in the conflict.

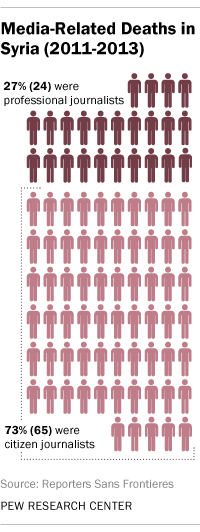

Since RSF began reporting the deaths of citizen-journalists and netizens in 2011, there have been 68 lives lost worldwide. Nearly all of these deaths—65—have been in Syria: four in 2011, 46 in 2012 and 15 (thus far) in 2013. Put another way, citizen-journalists and netizens have accounted for over 70% of all of the Syrian media-related deaths, according to RSF numbers.

Aside from the citizen journalist casualties, the dangers faced by professional journalists also continue, most recently after the explosion of deadly violence in Egypt. On August 14, The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) reported a grim statistic: The death in Cairo of Sky News cameraman Mick Deane brought the worldwide total of journalists, professional and non-professional, who have been killed in the line of duty in the past 21 years to 1000. According to CPJ, a total of nine journalists have lost their lives in Egypt since that organization first began tracking deaths in 1992.

Aside from the citizen journalist casualties, the dangers faced by professional journalists also continue, most recently after the explosion of deadly violence in Egypt. On August 14, The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) reported a grim statistic: The death in Cairo of Sky News cameraman Mick Deane brought the worldwide total of journalists, professional and non-professional, who have been killed in the line of duty in the past 21 years to 1000. According to CPJ, a total of nine journalists have lost their lives in Egypt since that organization first began tracking deaths in 1992.

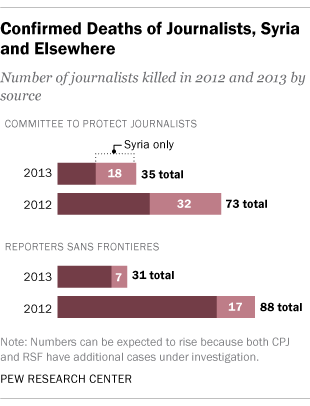

But as is the case with citizen journalists, it is in neighboring Syria where professional journalists report under conditions that pose greater risks than in any other country in the world. Although CPJ and RSF differ slightly in their methodologies, they are in agreement that Syria has become the most lethal country in the world for the media. Of the total of 108 deaths worldwide confirmed by CPJ since the beginning of 2012, 50 were in Syria. Of the 119 deaths confirmed by RSF for that same time period, 24 were in Syria.

Since the beginning of the uprising in March 2011, Syria—never a friendly environment for reporters—has become even more inhospitable. The government has placed increasingly stringent restrictions on independent media and has effectively banned entry to almost all international press.

In addition to implementing these formal restrictions on freedom of the press, CPJ has reported that the government has frequently moved in many other ways to silence journalists—disabling mobile phones and the internet, hacking websites and instigating malware attacks. Amnesty International recently published a report documenting how both media professionals and citizen journalists have been targeted for killing, torture, abduction and intimidation—first by the Assad government but more recently by opposition forces as well.

These constantly changing on-the-ground realities—coupled with smartphones, satellite phones, communication technologies such as Skype, and social media platforms like Twitter, Facebook and YouTube—are producing a new kind of reporting about the Syrian conflict that demonstrates the impact of citizen journalists and netizens.

Dozens of international media outlets now rely on or supplement their reporting with information and video footage provided by citizen journalists. Soazig Dollet, who works on the Middle East and North Africa desk of RSF, explained both the significance and the shortcomings of this new breed of journalist in a country like Syria:

“The conflict is evolving every day…in order to cover the conflict, there is no other choice than citizen-journalists to get the images out. But that does not mean the conflict is properly covered: both, the authorities and armed opposition groups, are spreading disinformation. And despite the emergence of citizen media—usually pro-revolution—there are very few independent observers, and a very limited number of foreign correspondents.”

Note: The fifth paragraph of this post was modified on Aug. 29, 2013 to reflect that fact that CPJ’s count of journalists includes both professionals and freelancers. Some of those freelancers are citizen journalists.