Public attitudes about science-related issues are as varied as the science itself. People’s views about the effect of their government’s space program on society are generally positive, with many more saying it has mostly been a good than a bad thing for society. Public sentiment about developments in artificial intelligence (AI) is mixed; majorities in most of the Asia-Pacific publics surveyed see AI as having a positive effect on society, while views in places such as the Netherlands, the UK, Canada and the U.S. are closely divided on this issue. There are similar divides over the societal impact from workplace automation using robotics.

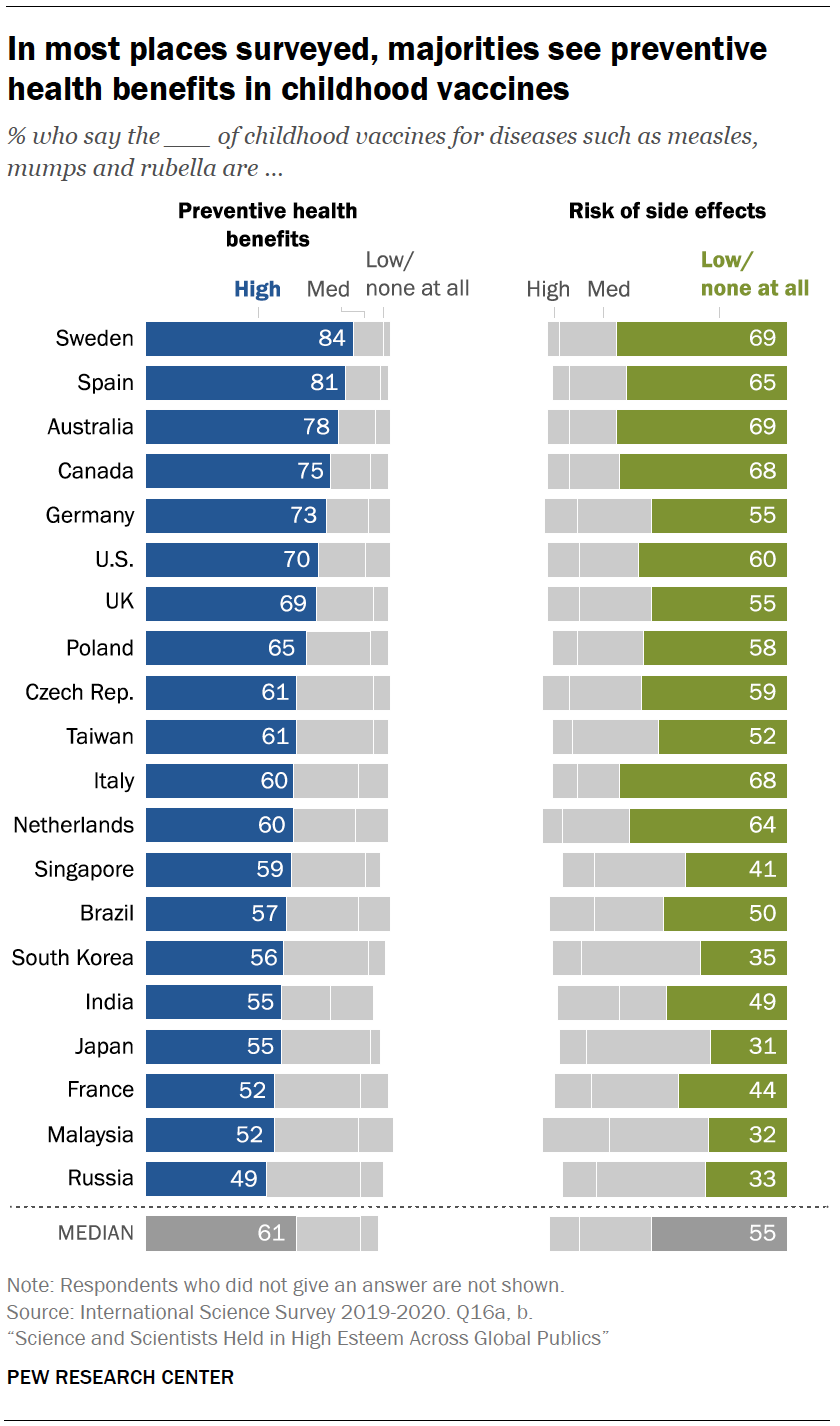

Beliefs about the preventive health benefits from childhood vaccines, such as those for the measles, mumps and rubella, run the gamut from 84% saying they are high in Sweden to 49% saying the same in Russia. A median of 55% across the 20 publics rate the risk of side effects from childhood vaccines as low or none, 29% say the risks are medium and 12% say they are high.

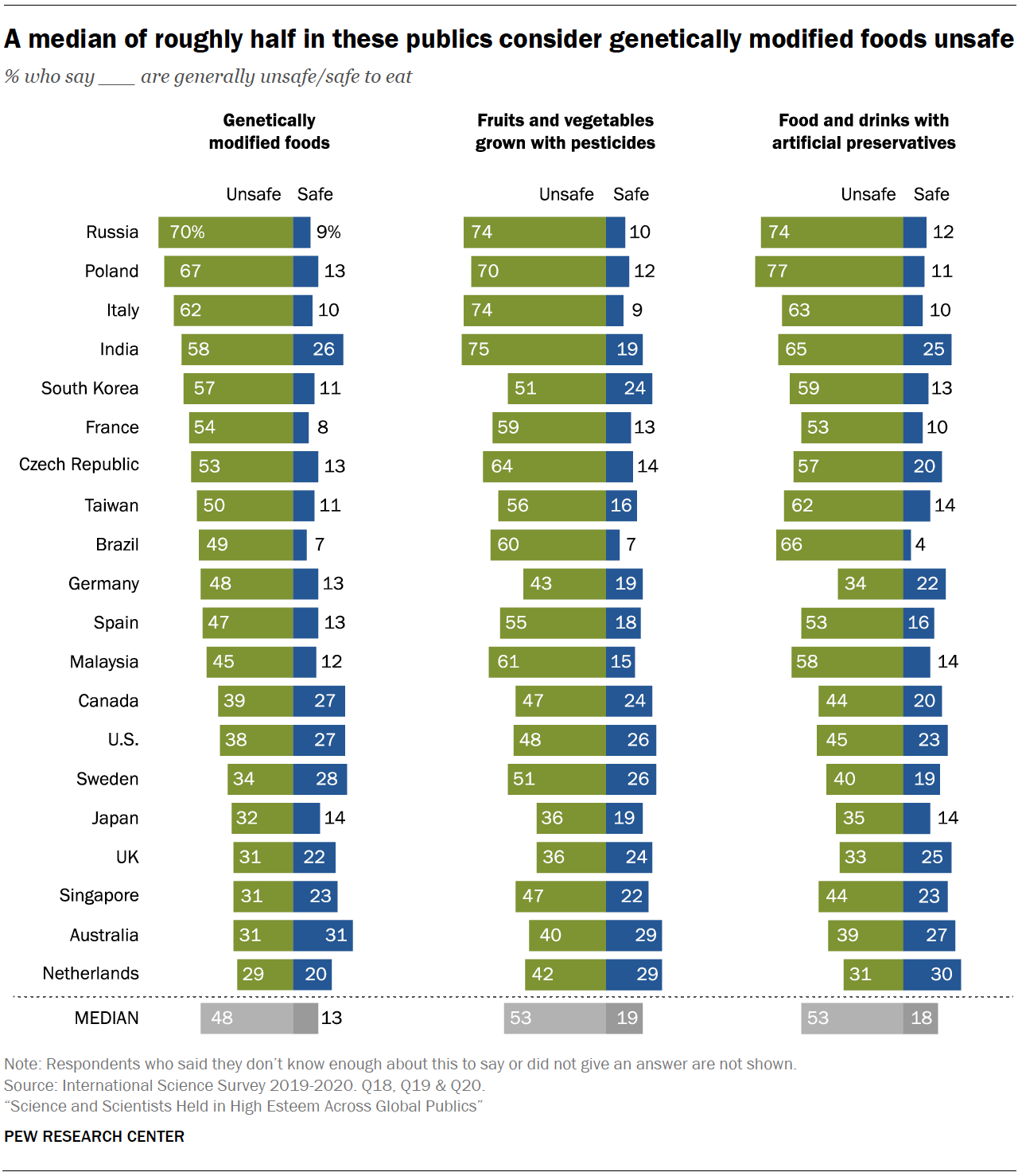

Majorities across these publics turn a cautious eye to foods grown or produced with techniques informed by science. Larger shares consider fruits and vegetables grown with pesticides to be unsafe more than safe to eat. The same pattern is found in views about food and drinks that contain artificial preservatives and beliefs about foods with genetically engineered ingredients, colloquially known as GMOs.

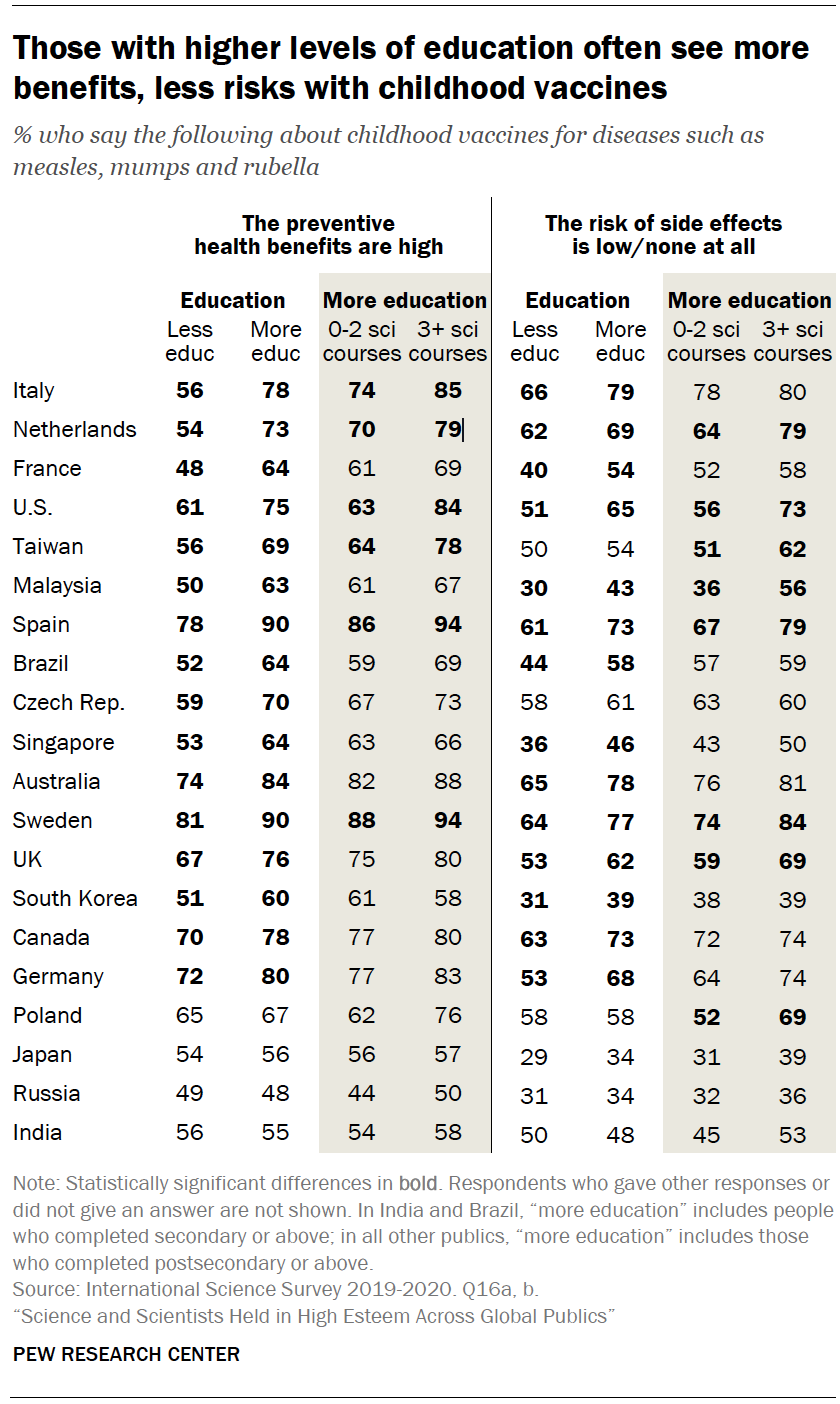

There is no single background characteristic that connects with how people view these issues. Education and science training are strongly related to beliefs about the preventive health benefits of childhood vaccines and the potential health risk from eating foods with GM ingredients. (Those with more education or more science training in secondary or postsecondary schooling are more convinced that childhood vaccines bring high preventive health benefits and are more likely to think GM foods are safe to eat.) But education is only a modest factor in other science-related beliefs.

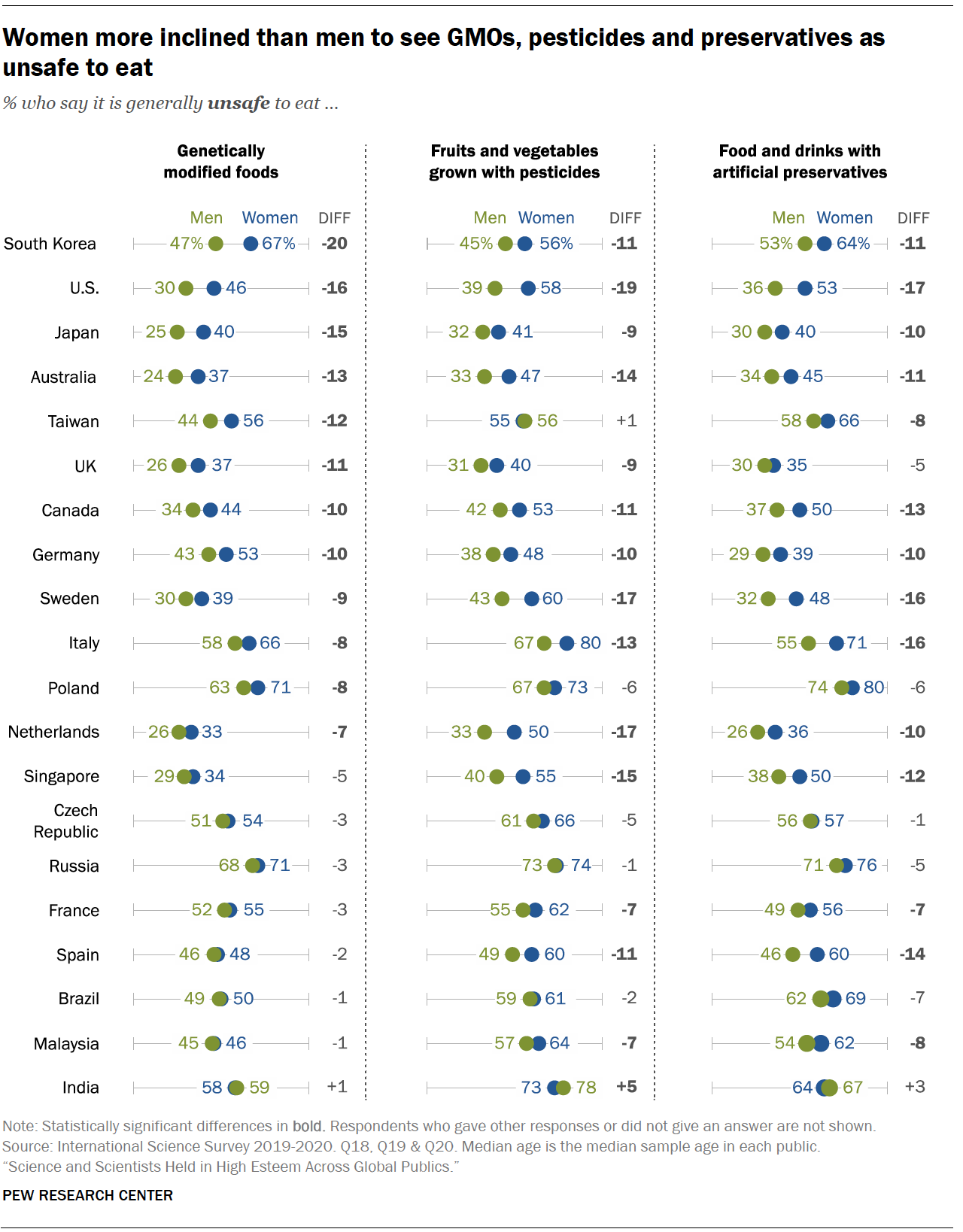

There are consistent gender differences on food issues, with women more likely than men to see each of the three food types considered in the survey as unsafe. Women are also less likely than men to think AI and job automation have been a good thing for society. On other science-related issues, however, there are no or only modest differences by gender.

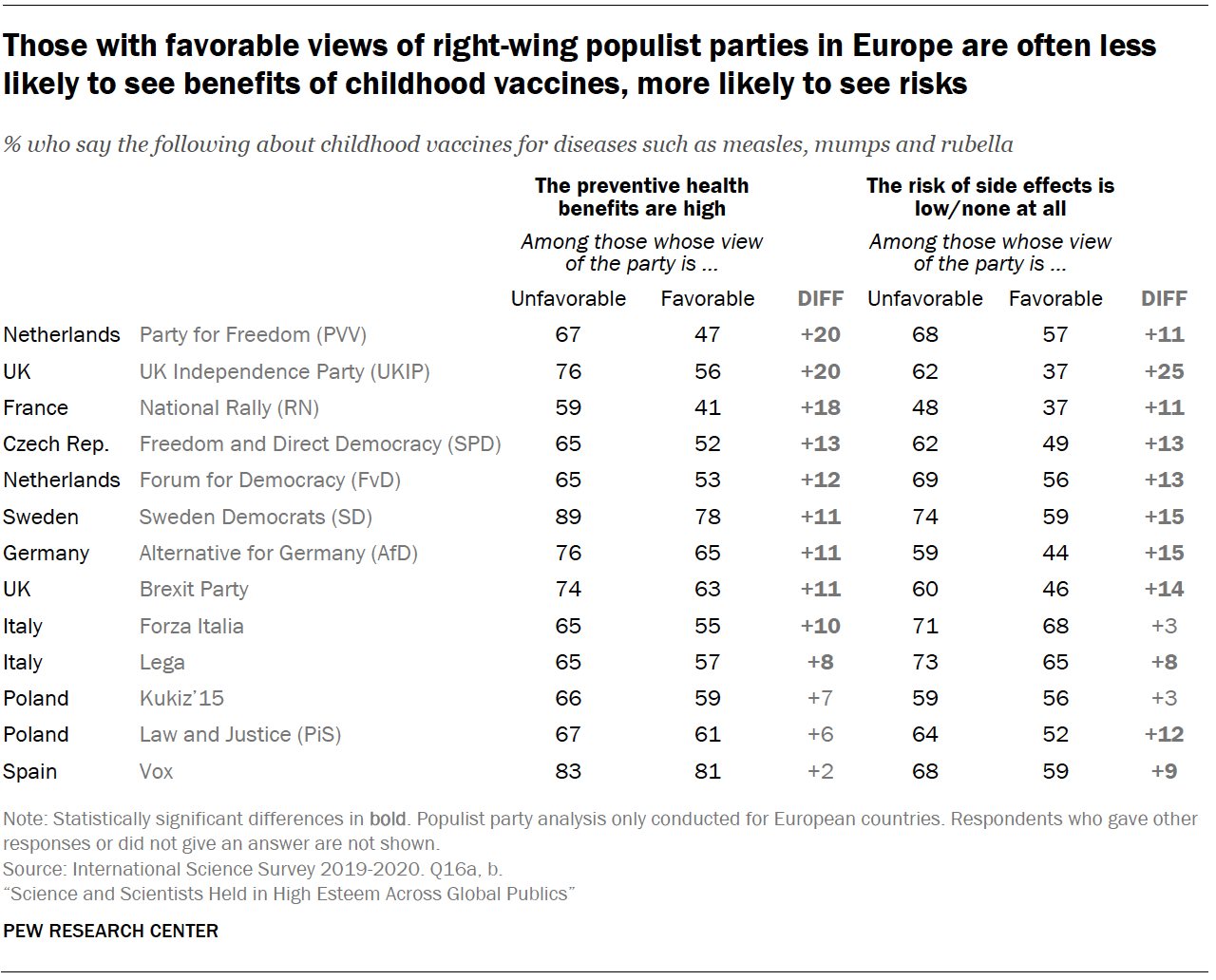

Political differences are quite wide in people’s views about climate, environment and energy issues. Ideology and support for right-wing populist parties are also a factor in people’s beliefs about childhood vaccines. But political identification is not a prominent factor in people’s views on other science-related issues such as AI or GM foods.

Publics often express mixed views on the impact of artificial intelligence and job automation

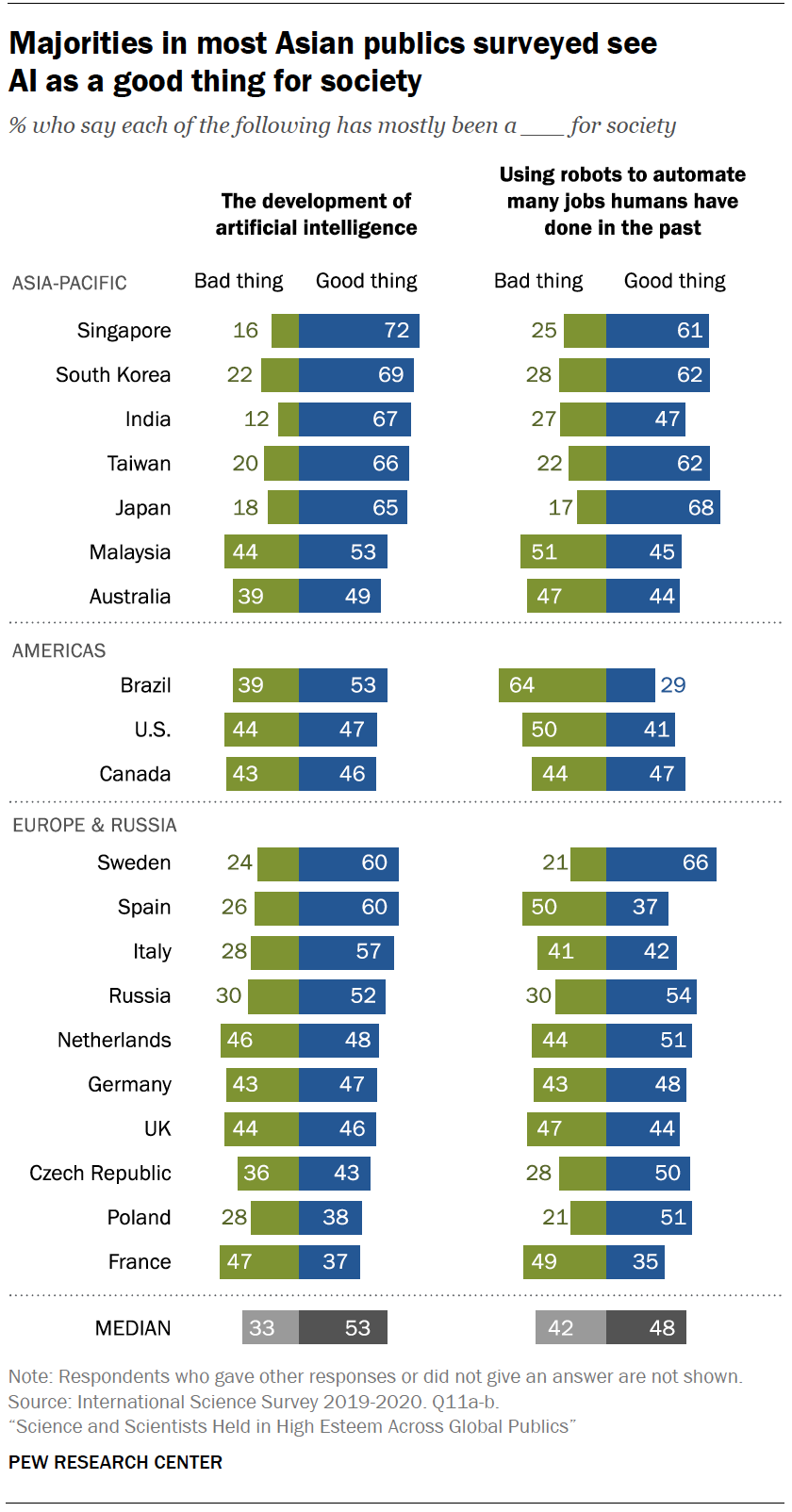

Across the 20 publics surveyed, a median of 53% say the development of artificial intelligence (AI) has mostly been a good thing for society, while a median of one-third (33%) say it has mostly been a bad thing; the remaining share volunteer that it’s been both, neither or say they don’t know.

Public opinion on AI varies among the places surveyed. Majorities in eight publics say artificial intelligence, described in the survey as computer systems designed to imitate human behaviors, has been a good thing. This includes about two-thirds or more in five of the six Asian publics surveyed, including Singapore (72%), South Korea (69%), India (67%), Taiwan (66%) and Japan (65%).

Publics surveyed outside of Asia tend to be more divided over the effects of AI for society, especially in the Netherlands, the UK, Canada and the U.S. In the Netherlands, for instance, about half (48%) think AI has been a good thing, while 46% say it has been bad for society. People in France are particularly skeptical: Just 37% say the development of artificial intelligence is a good thing for society.

Publics surveyed outside of Asia tend to be more divided over the effects of AI for society, especially in the Netherlands, the UK, Canada and the U.S. In the Netherlands, for instance, about half (48%) think AI has been a good thing, while 46% say it has been bad for society. People in France are particularly skeptical: Just 37% say the development of artificial intelligence is a good thing for society.

Ambivalence in some European countries about the development of AI echoes findings from a November 2019 Eurobarometer survey, which found Europeans overwhelmingly want to be informed when digital services or applications use artificial intelligence. In addition, about four-in-ten Europeans said they were concerned about the potential uses of AI leading to “situations where it is unclear who is responsible,” such as traffic accidents caused by autonomous vehicles. About a third were worried that the use of artificial intelligence could lead to more discrimination or to situations where there is nobody to complain to when problems occur. On the positive side, the Eurobarometer survey found half of Europeans thought AI could be used to improve medical care.

The Pew Research Center survey finds that publics offer mixed views about the use of robots to automate jobs. Across the 20 publics, a median of 48% say such automation has mostly been a good thing, while 42% say it has been a bad thing.

Majorities in four Asian publics see automation as good for society – Japan (68%), Taiwan (62%), South Korea (62%) and Singapore (61%) – as do about two-thirds (66%) in Sweden. Brazilians are the least likely to see this as a positive for society (29%), with nearly two-thirds (64%) saying the use of robots to automate human jobs has mostly been a bad thing for society.

A 2018 survey by the Center found people in both developed and emerging economies were concerned about job automation and its potential to displace workers and exacerbate the gap between rich and poor. Brazilians, for instance, overwhelmingly said using robots and computers to do work currently done by humans would make it harder for people to find jobs (83%) and make inequality worse (80%).

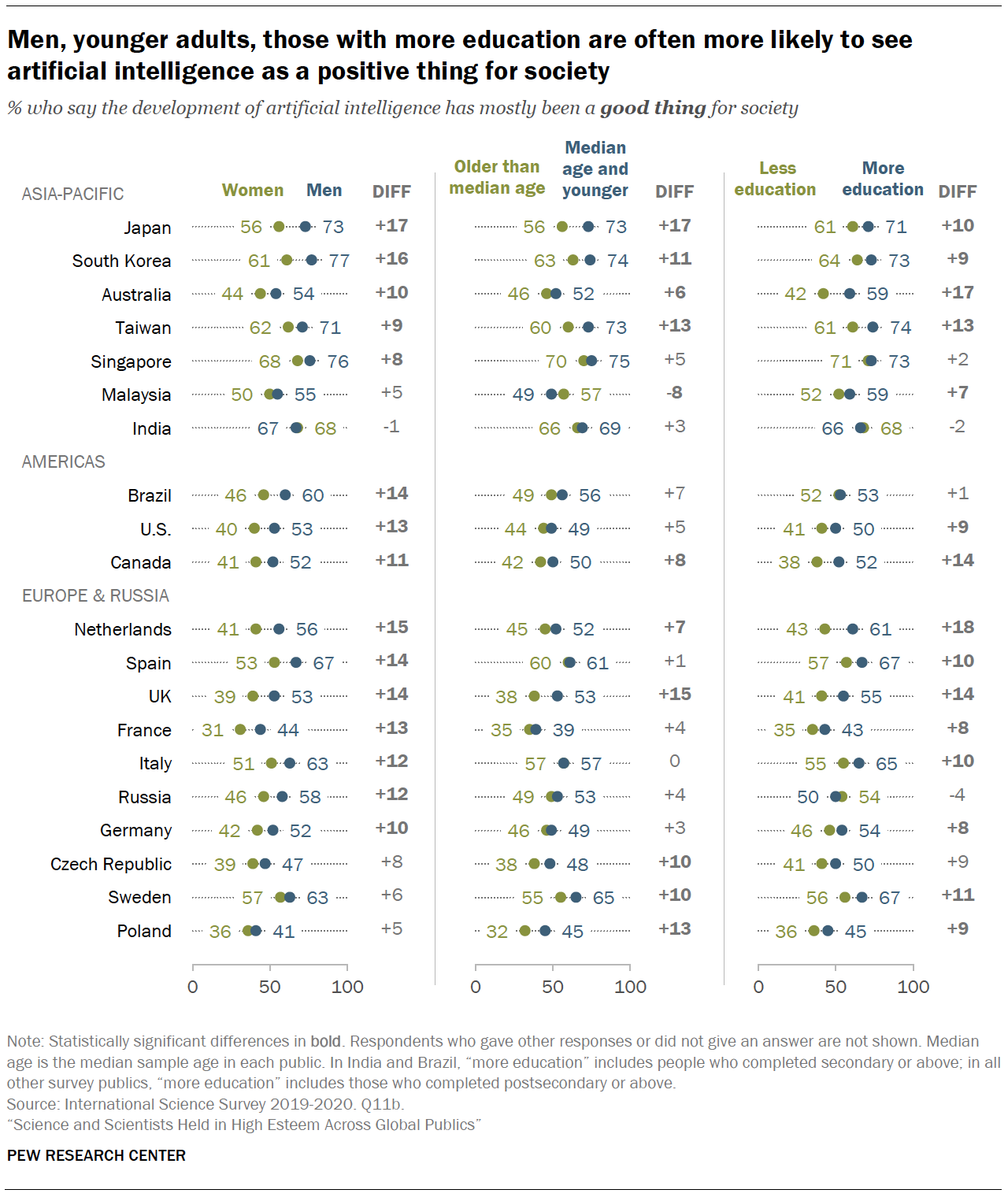

Men, more educated people often feel more positively about AI and robotics in the workplace

In most publics, men feel more positively about AI than women do. In Japan, for instance, about three-quarters of men (73%) say artificial intelligence is a good thing, compared with 56% of women, a gap of 17 percentage points. A similarly sized gender gap is seen in South Korea, where more men than women (77% vs. 61%) say the effects of AI have been mostly positive.

Education also plays a role in views of AI. People with more education – those with a secondary education or more in Brazil and India or a postsecondary education or more in other survey publics – are generally more positive in their assessment of AI. In Australia, for example, 59% of people with higher levels of education think AI has mostly had a good impact on society, compared with 42% of those with less education. (Note, however, that within the more educated group, there is little difference between people who took three or more science courses and those who took fewer. Science training itself is not strongly associated with views on AI.)

Age is also sometimes a factor in views of AI. In 10 publics, younger people (those who are at or younger than the median age in the survey public sample) are more likely than older adults to say the development of artificial intelligence has been good. In Malaysia, the pattern is reversed, with older adults seeing AI more positively than younger adults (57% vs. 49%, respectively).

View about how AI has impacted society are similar across ideology groups in most publics surveyed.

View about how AI has impacted society are similar across ideology groups in most publics surveyed.

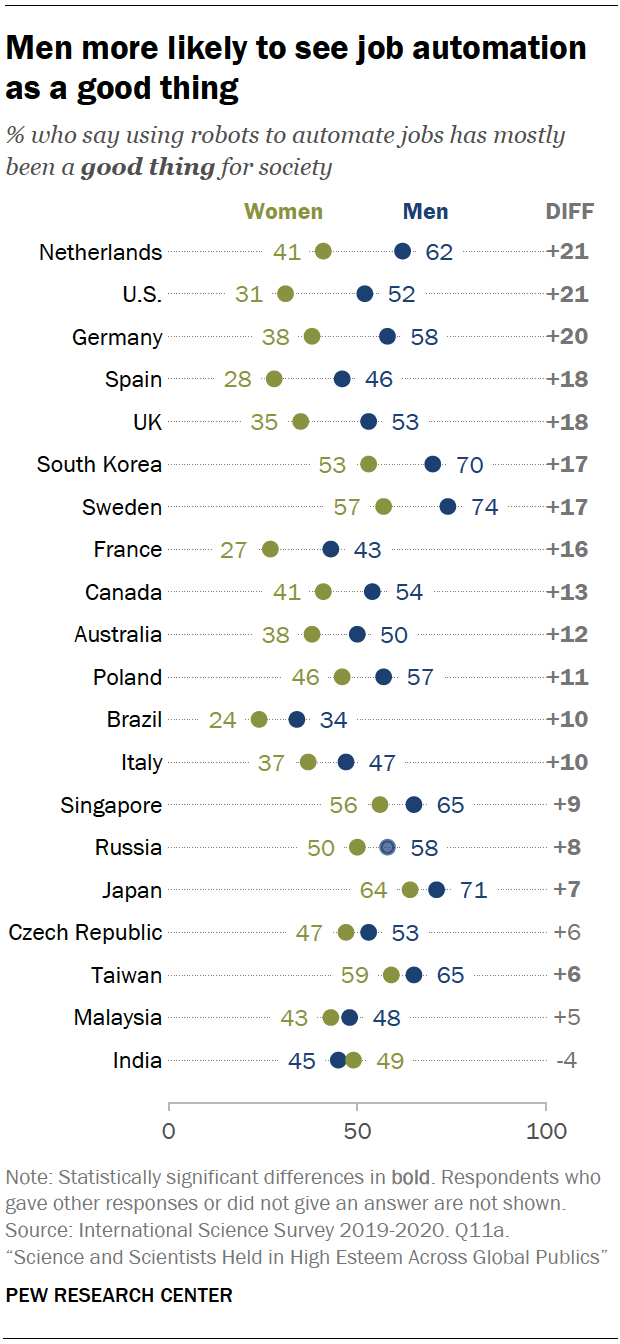

As with views about AI, the Center survey finds men are more likely than women to say the use of robots to automate jobs has been a good thing in most publics surveyed. In the Netherlands, for instance, 62% of men say automation has been mostly good for society, compared with 41% of women. There are similarly wide gender divides on this issue in the U.S. (52% of men vs. 31% of women) and Germany (58% vs. 38%).

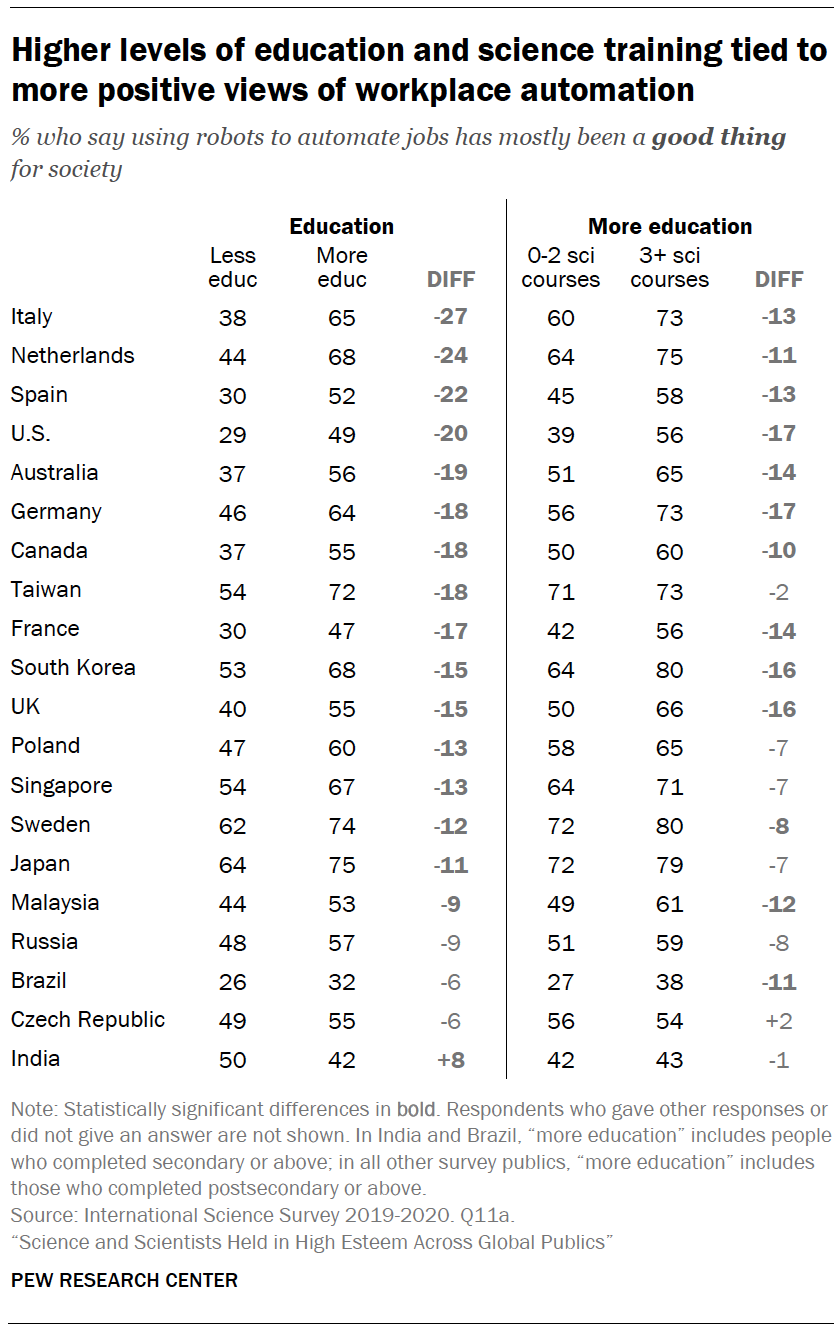

People with higher levels of education and those with more science training are more likely to think automation is a positive for society. For example, a majority of Italians with postsecondary education or higher (65%) say using robots to automate jobs is a good thing, while only 38% of those with less education say the same.

Among those with higher levels of education, people who took three or more science courses tend to see automation as more positive than those who took fewer science courses. This pattern exists in 13 of the 20 publics surveyed. In Germany, for instance, about three-quarters of those with postsecondary education or above who took three or more science courses (73%) say automation is a good thing for society, compared with 56% of those who took fewer science courses.

Among those with higher levels of education, people who took three or more science courses tend to see automation as more positive than those who took fewer science courses. This pattern exists in 13 of the 20 publics surveyed. In Germany, for instance, about three-quarters of those with postsecondary education or above who took three or more science courses (73%) say automation is a good thing for society, compared with 56% of those who took fewer science courses.

In most places, age and ideology are not strongly related to views of automation. Similarly, in the European countries surveyed, people with a favorable view of a right-wing populist party in their country generally hold similar views about the effect of robotics in the workplace as do others in the survey public.

While many see childhood vaccines as bringing high preventive health benefits, in some places sizable shares are not fully convinced

Across publics, majorities generally hold favorable views of the preventive health benefits from childhood vaccines, such as the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine (MMR), and tend to consider the risk of side effects as low. Still, there is considerable range in how widely these views are held across publics.

Across publics, majorities generally hold favorable views of the preventive health benefits from childhood vaccines, such as the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine (MMR), and tend to consider the risk of side effects as low. Still, there is considerable range in how widely these views are held across publics.

Public health experts often point to vaccines as one of the most important tools available to curb the spread of infectious disease. But their effectiveness depends on widespread access and “uptake” of vaccines on a recommended schedule specific to each disease.

Outbreaks of the measles in the U.S. and elsewhere were linked with lower rates of immunization for the disease in recent years. And concerns about vaccine hesitancy as well as communities espousing “anti-vax” views have grown in the U.S. and elsewhere.

A majority of adults in 17 of the 20 publics surveyed rate the preventive health benefits from childhood vaccines to be high. But there are only a handful of publics – Sweden, Spain and Australia – where about eight-in-ten or more are convinced of the high preventive health benefits. The shares who take this view are closer to six-in-ten in several places, including Italy, the Netherlands and Singapore. Russia (49%), France (52%) and India (55%) are among survey publics least likely to rate the preventive health benefits of vaccines as high.

Concerns about the risk of side effects from childhood vaccines also vary across publics, though they tend to be low in most places. For instance, in Sweden, Australia, Italy and Canada, nearly seven-in-ten say there is no or only a low risk of side effects from childhood vaccines. Somewhat smaller majorities say this in other places, including the U.S. (60%) and the Czech Republic (59%). In some publics, people are more skeptical. Half of Japanese adults say the risk of side effects is medium and 11% view it as high (31% say there is no or low risk). About half or more also consider the risk of side effects to be medium or high in Malaysia, Russia, South Korea, France and Singapore.

These patterns are broadly consistent with 2018 Wellcome Global Monitor data that found lower shares convinced that vaccines are safe in Japan, South Korea, France, Russia and Taiwan.

People with more education are often more convinced that childhood vaccines bring health benefits with little risk

People with more education tend to rate the preventive health benefits of childhood vaccines higher – and the risk of side effects as lower – than those with less education. This pattern occurs in most of the 20 publics surveyed.

People with more education tend to rate the preventive health benefits of childhood vaccines higher – and the risk of side effects as lower – than those with less education. This pattern occurs in most of the 20 publics surveyed.

In some places, science training is also related to beliefs about childhood vaccines. In six publics, those with higher levels of education who have also completed at least three science courses are more convinced than those with higher levels of education but few science courses that childhood vaccines bring high preventive health benefits. A similar pattern holds in eight publics for views that the risk of side effects from childhood vaccines are low or nonexistent.

Those with right-leaning political views and favorable ratings of right-wing populist parties are sometimes less convinced about benefits of childhood vaccines

In some publics, ideology and views of right-wing populist parties are related to beliefs about childhood vaccines. Those who place themselves on the right in terms of political ideology are less likely than those on the left to say that the benefits of childhood vaccines are high in Australia, Italy, the UK, Germany, Canada and the U.S. Similarly, in six of 14 publics where political ideology was measured, those on the ideological right are less likely than those on the left to rate the risk of side effects as low or none. See Appendix A for details.

In seven of the nine European nations surveyed, people who view their country’s right-wing populist party (or parties) favorably are less likely to say childhood vaccines have high preventive health benefits. For instance, 47% of Dutch adults who view the Party for Freedom (PVV) favorably say these vaccines are highly beneficial, compared with 67% of people who hold unfavorable views of PVV.

Similarly, in European publics, those with favorable views of right-wing populist parties are generally less likely than those with unfavorable views to say the risk of vaccine side effects are low or nonexistent.

Many see foods with genetically modified ingredients, artificial preservatives or grown using pesticides as unsafe

In many publics around the world, people tend to turn a cautious eye to the safety of eating foods that contain genetically modified ingredients or artificial preservatives or, in the case of produce, have been grown with pesticides.

Modern developments in the cultivation and production of food have come under scrutiny from health advocates, particularly among those who believe organic and less processed foods are better for one’s health. A 2016 report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine highlighted consensus among scientific experts in the U.S. that GM foods were safe. In 2019, an expert panel in Japan came to the same conclusion.

Crops or foods with genetically engineered ingredients, commonly referred to as genetically modified organisms or GMOs, face a complex and varying regulatory market around the world. Many European countries, such as France and Germany, have banned growing GM crops. The European Union also has some of the most stringent labelling requirements in the world. Japan and some other Asian publics, such as South Korea, also restrict commercially grown GM crops and require labeling of such foods. The U.S. and Brazil generally have more favorable regulations for GM crops and are among the world’s largest producers of such crops.

Across most of the publics surveyed, larger shares believe foods with GM ingredients are unsafe to eat than say they are safe (20-public median of 48% to 13%). A substantial share in some publics report that they don’t know enough about such foods to say (20-public median of 37%). Russians are particularly likely to think that GM foods are unsafe to eat (70%). Just 9% of Russians say such foods are safe and 18% don’t know enough to say either way. Australians are evenly divided with 31% each saying such foods are safe and saying such foods are unsafe. In places where GM foods are more restricted, the share saying they don’t know enough to say tends to be higher. For example, about half of the public in Japan (51%) and the Netherlands (50%) don’t have an opinion on this issue.

Public skepticism is also strong when it comes to judgments about the safety of produce grown with pesticides and food and drinks that contain artificial preservatives. For both types of foods, a median of 53% say they are unsafe to eat, with far fewer saying that each type of food is safe.

In Russia and Poland, two-thirds of the public or more consider each of the three food types to be generally unsafe to eat. Italy and India have majorities who consider each of these three types to be unsafe.

Women often more likely than men to see a health risk from consuming foods with GMOs, pesticides and artificial preservatives

Women are more likely than men to consider foods with genetically modified ingredients unsafe to eat. This pattern occurs in 12 out of 20 places surveyed. Similarly, in most of these places, more women than men say that both fruits and vegetables grown with pesticides and food and drinks with artificial preservatives are unsafe.

Gender differences in the U.S. are among the largest across these publics for all three types of foods. A 2019 U.S. survey by the Center also found women more likely than men to say that GM foods are worse for health than conventionally grown foods (58% vs. 42%).

In many of these publics, people with more education, and specifically those who have also taken at least three science courses during their secondary or tertiary schooling, are more likely to see these foods as safe to eat. Education and science training differences in views about GM foods are particularly wide. For example, in the Netherlands, 27% of those with at least some postsecondary education who completed two or fewer science courses consider GM foods to be safe, while half (50%) of those who completed at least three science courses say the same. (See details in Appendix A.)

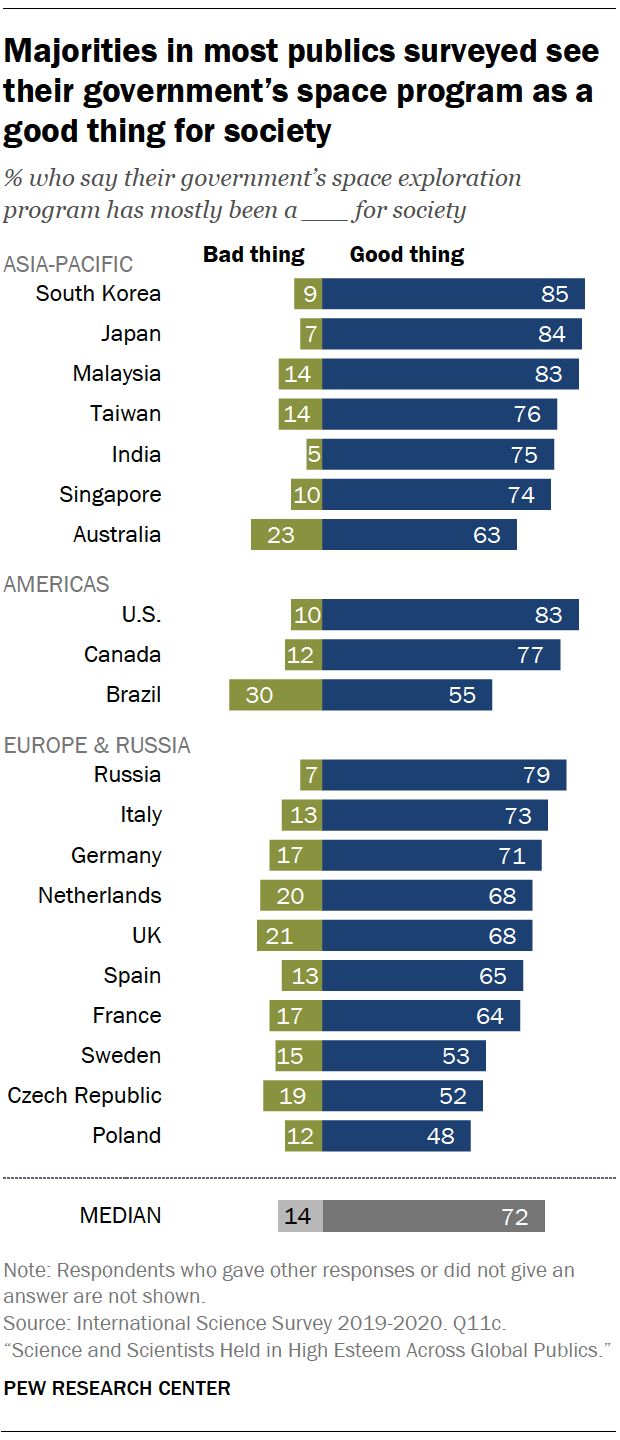

Space programs are generally seen as having a positive impact on society

Majorities in most publics see their government’s space exploration program as a good thing for society. Among the 20 publics surveyed, a median of 72% say their government’s space exploration program has mostly been a good thing for society. This includes about eight-in-ten or more in South Korea (85%), Japan (84%), the U.S. (83%), Malaysia (83%) and Russia (79%). (See Topline for the space programs included in the survey.)

Majorities in most publics see their government’s space exploration program as a good thing for society. Among the 20 publics surveyed, a median of 72% say their government’s space exploration program has mostly been a good thing for society. This includes about eight-in-ten or more in South Korea (85%), Japan (84%), the U.S. (83%), Malaysia (83%) and Russia (79%). (See Topline for the space programs included in the survey.)

In Europe, opinion about the European Space Agency (ESA) – an intergovernmental organization with 22 member states – also tilts to the positive. Majorities in Italy (73%), Germany (71%), the Netherlands (68%), the UK (68%), Spain (65%) and France (64%) say the program has mostly been a good thing for society. In Sweden (53%), the Czech Republic (52%) and Poland (48%), about half of adults feel this way about the ESA.

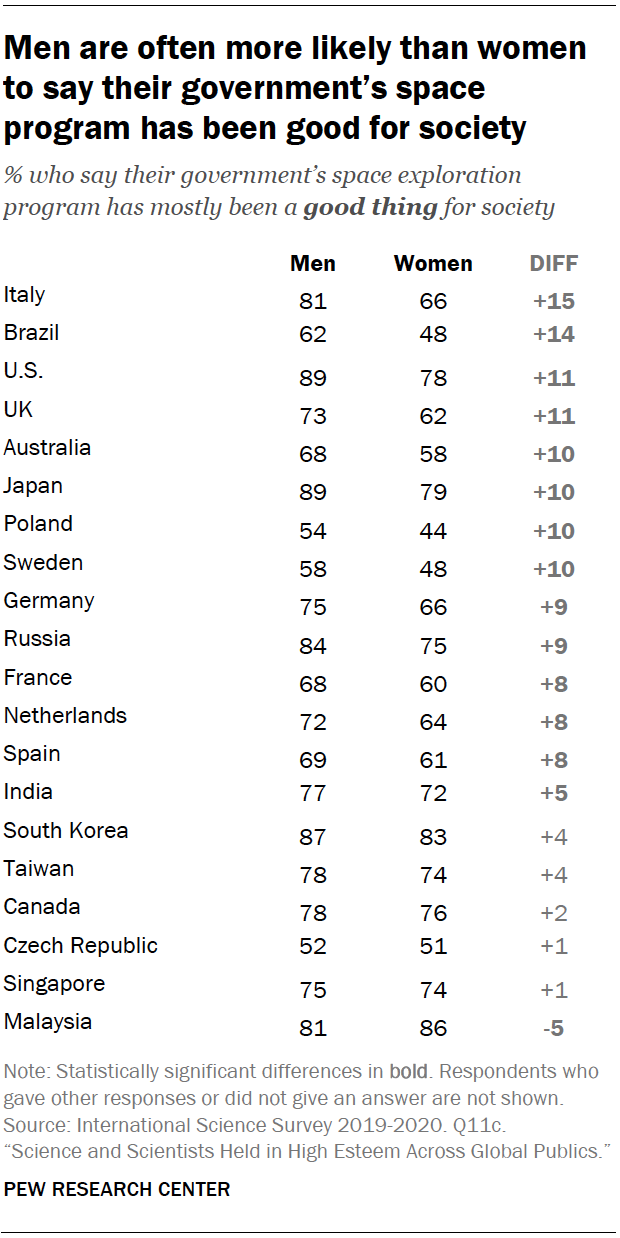

Men are often more positive than women about the impact of their space program on society. The gender gaps are largest in Italy, where 81% of men vs. 66% of women see their country’s space program as a good thing for society, and Brazil (62% vs. 48%, respectively). Only in Malaysia are women (86%) slightly more likely than men (81%) to say the space exploration program has been a good thing.

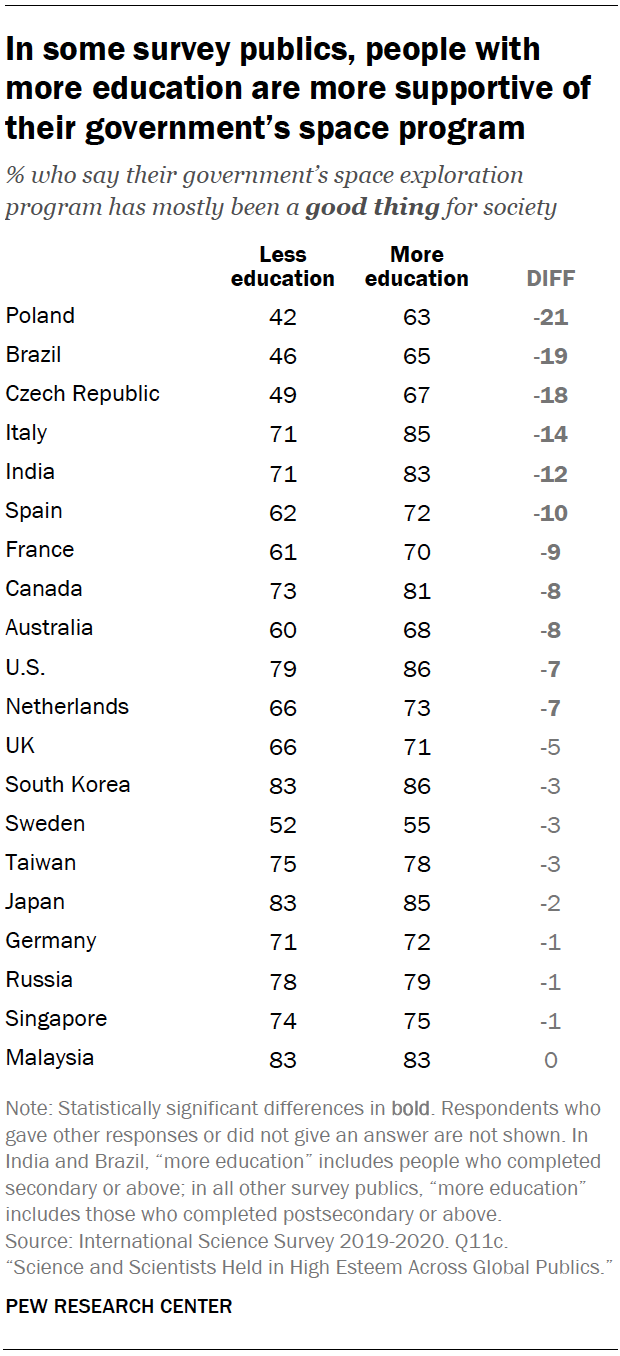

In 11 of the 20 survey publics, people with more education are more likely to see their government’s space exploration program as a “good thing” for society. In Poland, for example, a majority of those with postsecondary education or higher (63%) say their space program has been good for society, compared with 42% of people with less education. The gap between more and less educated people is similarly large in Brazil (65% vs. 46%, respectively) and the Czech Republic (67% vs. 49%).

Having completed science courses, however, is not a major factor in people’s views of space exploration programs. In addition, there are no differences in views – or only modest ones – by age or political ideology in assessments of space exploration programs.

Fact Sheets: Public Views of Science Around the World

Fact Sheets: Public Views of Science Around the World