Looking across the 20 publics surveyed, majorities considered their medical treatments to rank above those of other publics globally. Views of medical treatments were often seen more favorably than achievements in other areas, including science, technology, STEM education, politics and the economy. In the U.S., however, 61% said their scientific achievements were at least above average, while more – 55% – said the same about their medical treatments. And in India, similarly sized majorities saw their country as above average or the best in the world across a number of areas. (The survey was conducted before the coronavirus outbreak reached pandemic proportions.)

Large majorities saw value from government investment in scientific research, saying that such investment is usually worthwhile for society over time. Majorities also generally considered it at least somewhat important to be a world leader in scientific research. But the share who considered their scientific achievements at least above average often lagged behind the share saying it was very important to be a world leader in science.

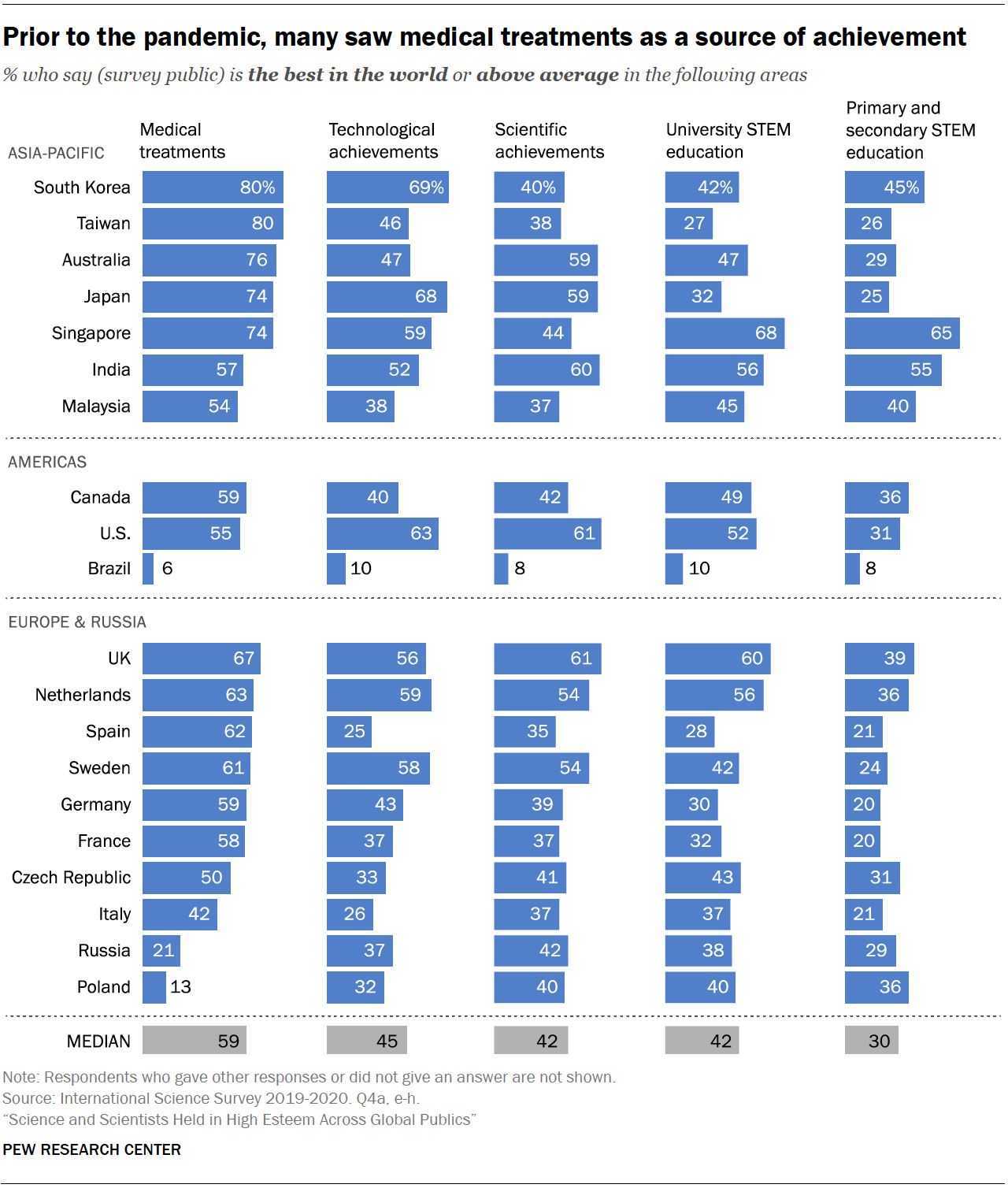

Many see their medical treatments in a favorable light; fewer say the same about STEM education for primary and secondary school students

Across the 20 publics, a median of 59% say their medical treatments are at least above average, with some of the highest ratings in the Asia-Pacific region. In South Korea and Taiwan, for example, 80% say their medical treatments are at least above average. By contrast, only 6% in Brazil and 13% in Poland think their medical treatments are the best in the world or above average.

Medians of 45% and 42% say their technological and scientific achievements are at least above average, respectively. Perceptions of areas of relative strength vary by public. In the UK, the U.S. and Japan, majorities give positive ratings to both their technological and scientific achievements. In South Korea and Singapore, majorities think their technological achievements are at least above average, but fewer than half say the same about scientific achievements. In Australia the opposite pattern occurs, with a smaller share giving their technological than scientific achievements high marks.

When it comes to education in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM), a median of 42% see their publics’ university STEM training as above average or the best in the world. Ratings are far lower when it comes to STEM education at the primary and secondary school levels: Across the 20 publics surveyed, a median of 30% view the STEM education at these levels as at least above average.

Singaporeans stand out for their strongly positive ratings of their STEM education: 65% rate their STEM education in primary and secondary schools as at least above average. The city-state consistently ranks at or near the top in math and science on the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) of 15-year-olds. Singapore is also one of only a handful in which a majority (68%) rates their university STEM education as at least above average, along with the UK (60%), the Netherlands (56%) and India (56%).

Across all areas of achievement, ratings are particularly low in Brazil. Just 10% or fewer consider their medical treatments, technological or scientific achievements and STEM education to be at least above average. A majority of Brazilians (63%) consider their medical treatments to be below average; 41% say the same about the country’s scientific achievements. Brazilians’ views of the political and economic system are also quite negative. Fewer than one-in-ten say their country is the best in the world or above average in these areas; majorities say each is below average compared with other nations.

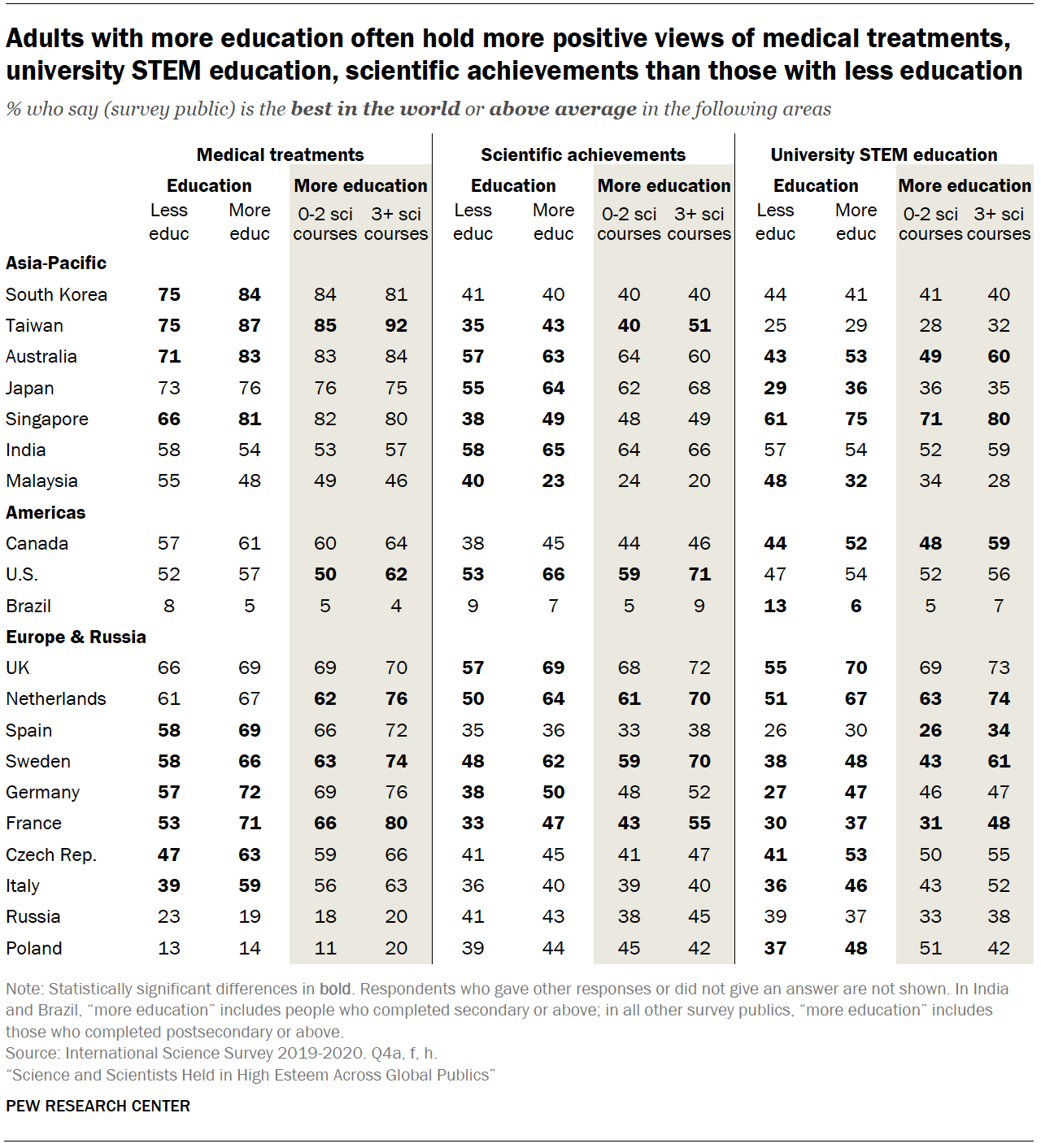

Those with more education tend to see their STEM-related achievements in a more favorable light

Across the 20 publics, those with more education often rank their medical treatments, university STEM education and scientific achievements more highly than those with less education. For example, 72% of Germans with a postsecondary education or more think the country’s medical treatments are at least above average compared with 57% of those with less education. Germans with more education are also more inclined than those with less education to say their university STEM education (47% vs. 27%) and scientific achievements (50% vs. 38%) are the best in the world or above average.

Malaysia stands out as the only survey public in which the pattern is reverse. Malaysians with at least a postsecondary education are less likely than others to see the country’s university STEM education or scientific achievements in a favorable light. Malaysians with a postsecondary education also tend to give lower marks to the country’s technological achievements as well as to its political system and economy.

While higher levels of education are often associated with more positive views of STEM-related achievements, postsecondary science training itself is not consistently tied to differences in these assessments. For instance, among those with a postsecondary education in Japan, 75% of those who took three or more science courses say their medical treatments are above average or the best in the world, compared with about as many (76%) who took zero to two science courses.

The absence of a relationship between postsecondary science training and ratings of medical treatments, scientific achievements and university STEM education is seen across many survey publics. However, Sweden, France and the Netherlands are exceptions to this general pattern. In these places, those who have at least a postsecondary education and who have completed three or more college-level science courses are more positive about the quality of their country’s medical treatments, university-level STEM education and scientific achievements than postsecondary graduates with less science training.

In many places, men are more likely than women to highly rank their countries’ accomplishments across a range of STEM-related areas, particularly in Europe. For example, in the Netherlands, men are more likely than women to say their country is at least above average in university STEM education (20 percentage point difference), medical treatments (by 18 points) and scientific achievements (18 points). There are similar differences between men and women in the ratings of medical treatments, university STEM education and scientific achievements in France, Italy, Germany and the UK. See details in Appendix A.

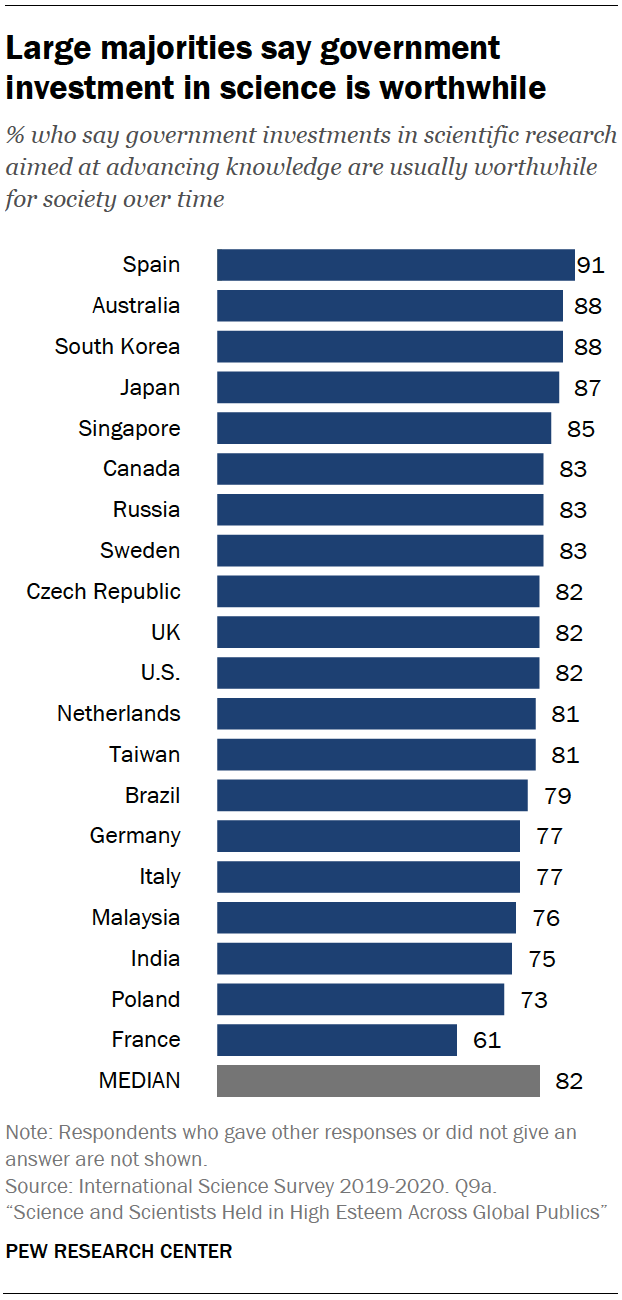

Majorities see government investments in scientific research as valuable; half or more think being a world leader in science is important

Overall, there is broad agreement among these 20 publics that government investment in scientific research is worthwhile. Large majorities in most publics surveyed say that government investment in scientific research aimed at advancing knowledge is usually worthwhile for society over time. Across all places surveyed, a median of 82% say this.

Overall, there is broad agreement among these 20 publics that government investment in scientific research is worthwhile. Large majorities in most publics surveyed say that government investment in scientific research aimed at advancing knowledge is usually worthwhile for society over time. Across all places surveyed, a median of 82% say this.

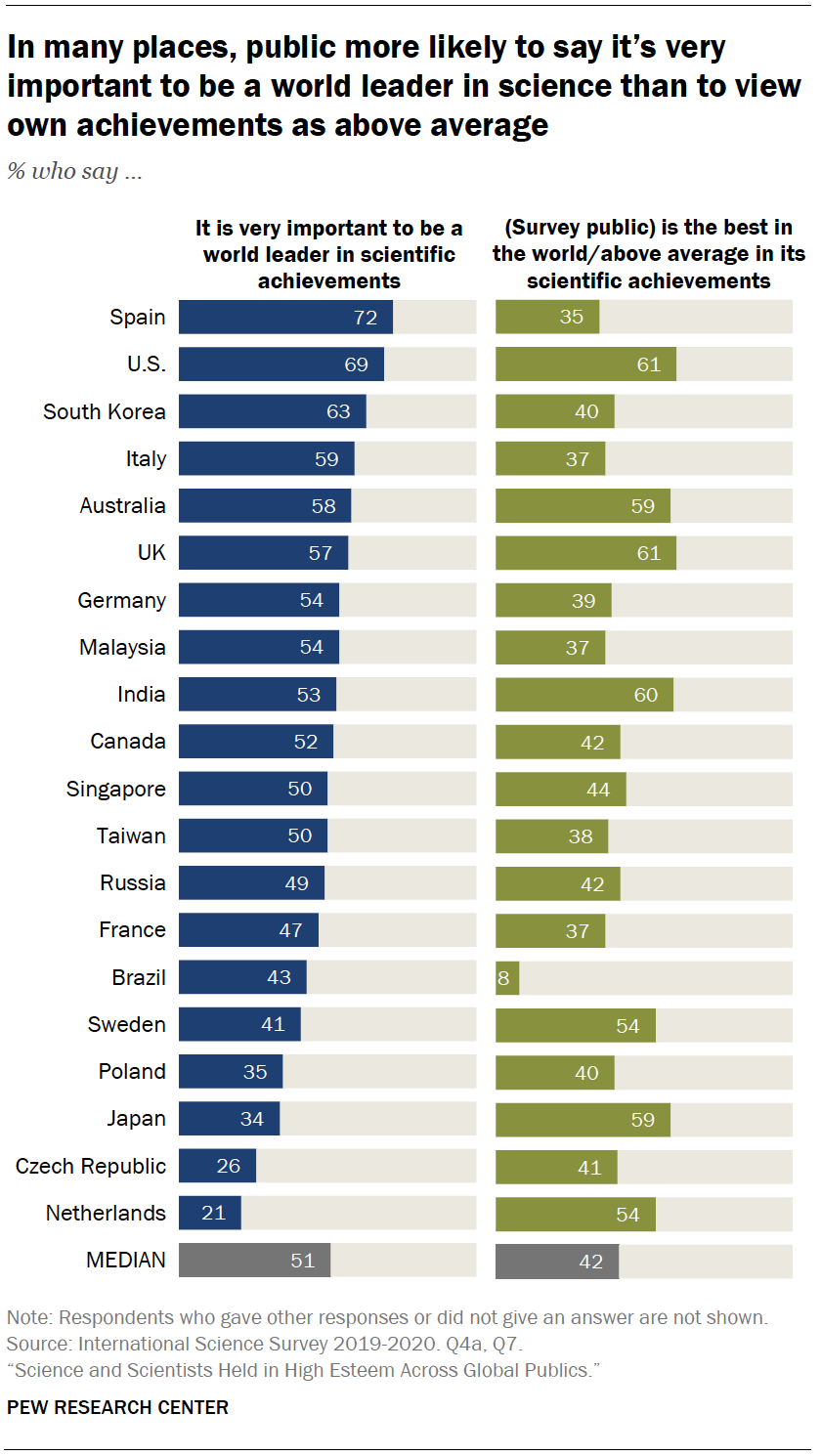

Further, majorities in all publics agree that being a world leader in scientific achievement is at least somewhat important. The share who view this as very important varies by public. A 20-public median of 51% place the highest level of importance on being a science world leader.

Assessments of where each public stands in its scientific achievements often lag behind the shares who aspire to be a world leader in science.

For example, 72% of Spaniards consider it very important to be a world leader in scientific achievement, but just 35% believe their country’s scientific achievements are the best in the world or above average.

For example, 72% of Spaniards consider it very important to be a world leader in scientific achievement, but just 35% believe their country’s scientific achievements are the best in the world or above average.

In a few places, the opposite pattern occurs. Among the Dutch, for instance, just 21% say it is very important to be a science world leader, while more than twice as many (54%) consider the nation to be at least above average in its scientific achievements.

People with higher levels of education are more likely than those with lower levels of education to think government investments in scientific research are worthwhile. There is a significant difference in views by level of education in 18 of the 20 publics surveyed.

In eight of 20 publics, people with more education are more likely than those with less education to say it is very important to be a world leader in scientific achievements.

Among those with higher levels of education, there is little difference in views on these two questions between those who have taken three or more science courses and those with less science training. See details in Appendix A.

Fact Sheets: Public Views of Science Around the World

Fact Sheets: Public Views of Science Around the World