Across the 20 places surveyed, there is relatively high trust in the military and scientists to do what is right for the public; trust tends to be lower in the national government, news media and business leaders, by comparison. Education and political ideology often play a role in people’s assessments of scientists, with highly educated people and those on the political left tending to express more trust in scientists than those with lower levels of education and those on the political right.

While political ideology, including views of right-wing populist parties, is often correlated with trust in scientists, it has only a modest connection with general views about whether scientists’ judgments are based solely on the facts or as likely to be biased as those of other people. In general terms, about half to three-quarters across all of these publics think it is better to rely on people with practical experience to solve pressing problems in society than to rely on those with expertise. Public skepticism of relying on experts, generally, is widely shared across those on the right and left.

Public trust in the news media is considerably lower than that for scientists in most places surveyed. However, majorities in 18 of the 20 survey publics give the media positive marks for their science news coverage. Further, majorities in most of these publics agree on at least one problem about the news: The general public doesn’t know enough about science to really understand coverage of scientific research.

Public trust in scientists rivaled that in the military at the onset of the pandemic

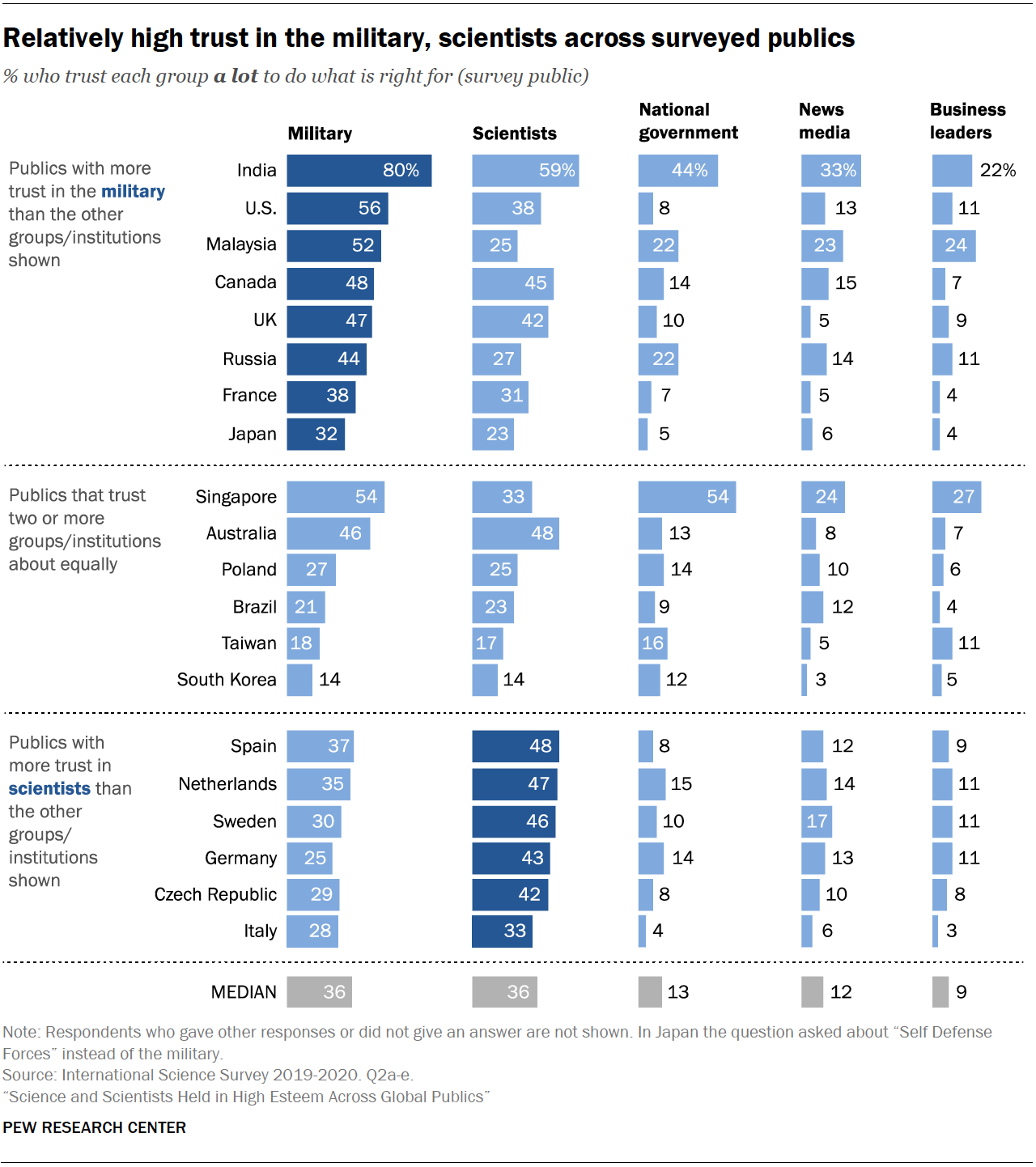

Majorities across publics say they have either a lot of trust or some trust in scientists to do what is right for the public. A 20-public median of 36% express the strongest level of trust in scientists to do what is right. Relatively few across most survey publics say they have not too much or no trust in scientists to do what’s right.

Overall, views of the military are similarly positive. In nearly all places, majorities have at least some trust in the military to do what is right for the public, and a median of 36% have a lot of trust (the same median as for trust in scientists).

However, the relative standing of trust in the military and scientists varies from place to place. In eight of the places surveyed, the military is more trusted than scientists, including in India, the U.S. and Russia. By contrast, in six publics – all in Europe, including the Netherlands, Sweden and Germany – greater shares have a lot of trust in scientists than in the military to do what is right. In five publics, no one group is trusted more than another, and trust in the military and scientists tends to be about the same. For example, 46% of Australians say they trust the military a lot, while 48% have a lot of trust in scientists.

Singaporeans stand out for comparatively high trust in their national government to do what is right for the country: 54% have a lot of trust in the national government, and the same share has a lot of trust in the military. By comparison, a third in Singapore have a lot of trust in scientists. (The language used to describe the national government varied modestly across survey publics; see topline for more details.)

In the large majority of publics surveyed, trust in the national government, news media and business leaders tends to be lower than that for the military and for scientists. Medians of roughly one-in-ten have a lot of trust in each of these groups and institutions to do what is right. And, the share with a negative view of each group is often sizable. For example, the share who report not too much or no trust in the news media to do what is right on behalf of the public is as high as 75% in France and 69% in South Korea.

In a majority of surveyed publics, people with more education are more trusting of scientists than those with less education

In 14 of the 20 publics, people with more education express higher levels of trust in scientists than those with less education. For example, 54% of Canadians with at least some postsecondary education have a lot of confidence in scientists compared with 33% of Canadians with a secondary education or below, a difference of 21 percentage points. There are differences in trust in scientists by education levels in a number of other places, including the UK, Brazil, Germany, the U.S. and Sweden.

In some places, trust in scientists is also higher among people who have taken three or more science courses as part of their postsecondary education than among those with less postsecondary science training. This is the case in the UK, the Netherlands, Australia, the U.S. and Taiwan. However, science training is not uniformly related to higher trust in scientists; in most places surveyed, there is no significant relationship between the two. See details in Appendix A.

Age can also play a role in views of scientists. Adults younger than the median age report higher levels of trust in scientists to do what is right than those older than the median age in eight of the publics surveyed. Overall, the magnitude of these gaps is relatively modest. For instance, in the UK, 47% of those younger than the median age trust scientists a lot to do what is right compared with 37% of people older than the median age. See details in Appendix A.

Levels of trust in scientists and the military differ by political ideology

The growth of right-wing populist movements in many European nations, along with anti-establishment rhetoric, has heighted concern about the degree to which the general public values expertise. Views of experts have been a flashpoint in political conversations in places around the world, including the U.S. and UK. British conservative politician Michael Gove said during debates around the economic impact of leaving the European Union that “people in this country have had enough of experts,” and in the U.S. President Donald Trump has often expressed a low opinion of experts.

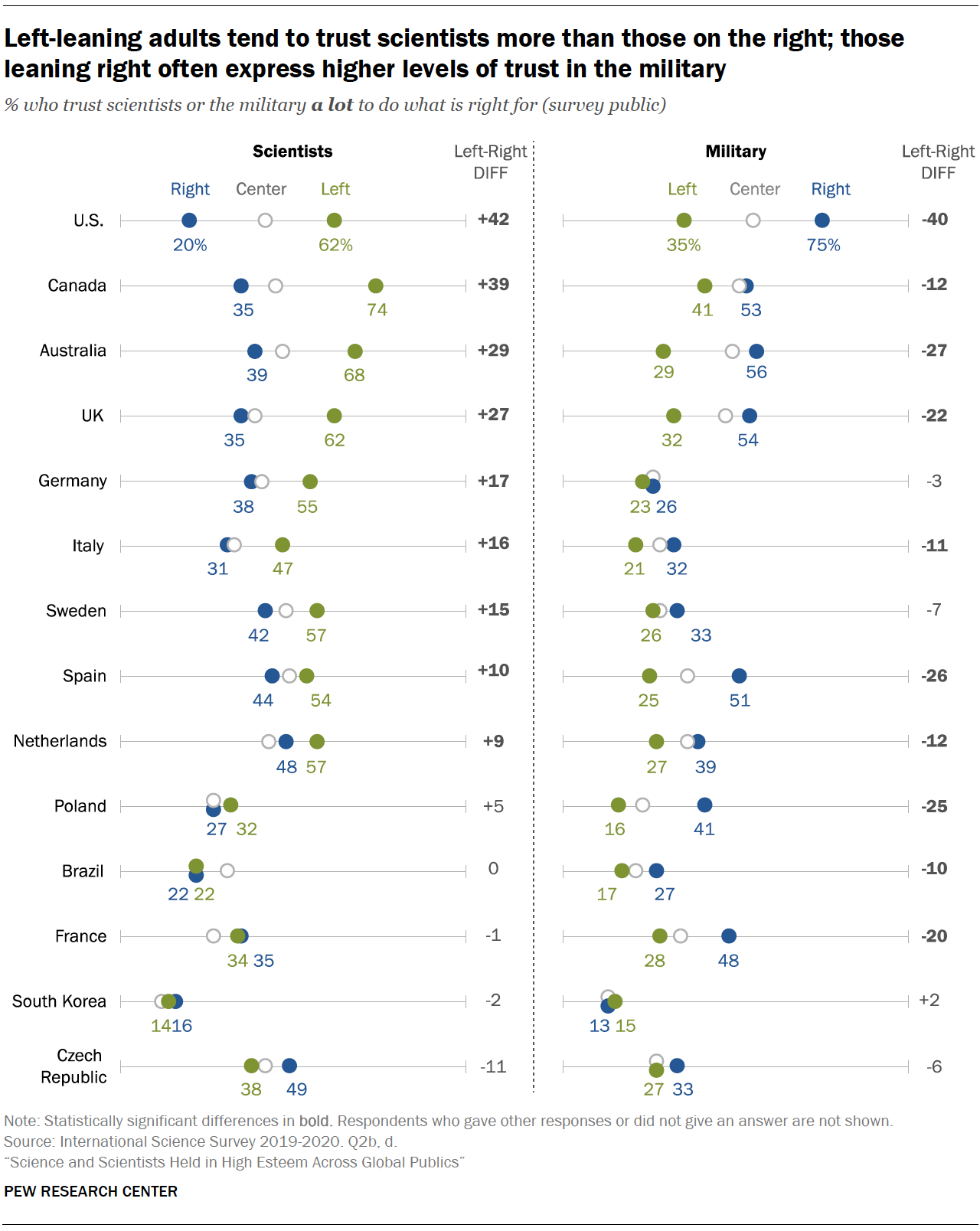

The Center’s survey finds differences by political ideology in views of scientists, as well as the military, with those who place themselves on the left of a scale of political ideology often expressing more trust in scientists – and less trust in the military – than those on the right.

There are especially large differences in trust in scientists and the military by political ideology in all four English-speaking countries surveyed (the U.S., Canada, Australia and the UK). Majorities of those who identify themselves as left-leaning in these places say they have a lot of trust in scientists to do what is right for the public, while fewer than half say this about the military. For example, 62% of those on the left in the UK have a lot of trust in scientists, while just 32% say this about the military. The pattern is the reverse among those on the political right. In the U.S., for instance, 75% of those on the right express the highest level of trust in the military, compared with 20% who have a lot of trust in scientists.

Trust in scientists also is higher on the left than the right in Germany, Italy, Sweden, Spain and the Netherlands. People who consider their ideological views to be on the right are more inclined to trust the military to do what is right, although the size of the difference varies across these countries. (People’s political ideology was asked in 14 of the 20 publics surveyed, primarily in Europe and the Americas.)

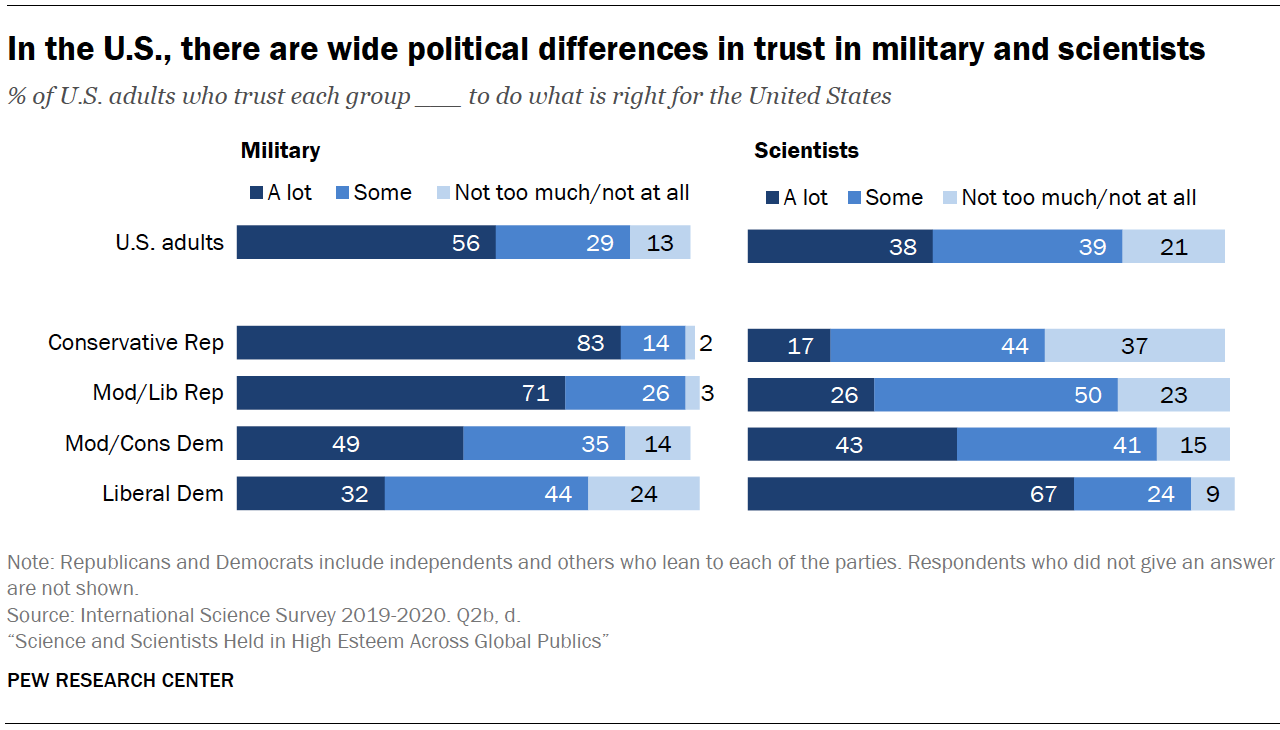

In the U.S., political ideology is closely tied to party identification. Analysis of partisanship and ideology shows very large differences between liberal Democrats and conservative Republicans in the levels of trust they express in scientists and the military.

Two-thirds of liberal Democrats have a lot of trust in scientists to do what is right for the country, compared with just 17% of conservative Republicans. By contrast, a broad majority of conservative Republicans (83%) have a lot of trust in the military to do what is right for the county, compared with 32% of liberal Democrats.

Publics skeptical that they should rely more on ‘experts’ to solve problems

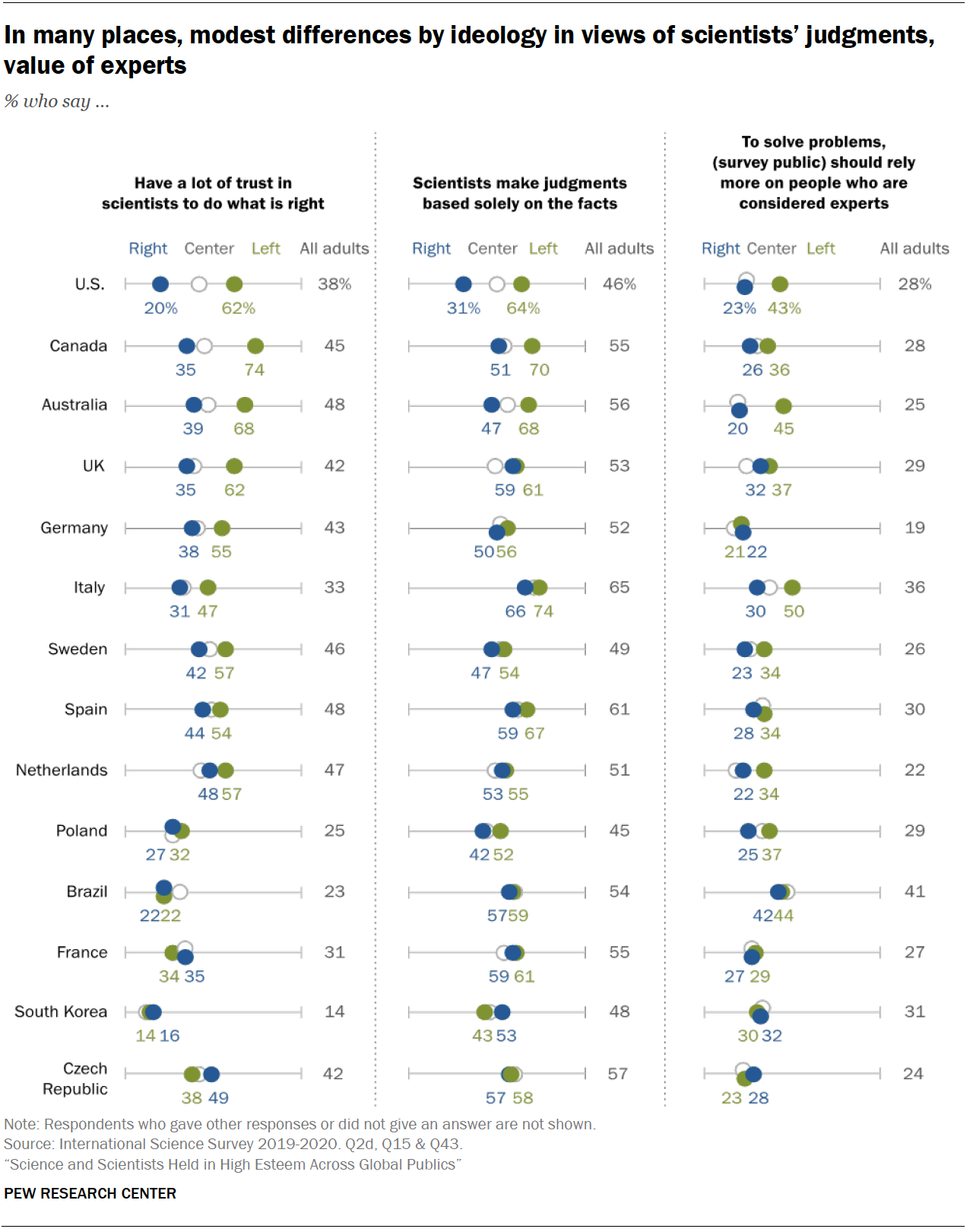

Across publics, there is skepticism about relying on experts to solve important problems over those with practical experience in the problem area. In all 20 publics, fewer than half think they should rely more on people who are considered experts in the area – even if they don’t have much practical experience – to solve pressing problems (median of 28%). In all places, larger shares say they should rely more on people with practical experience, even if they aren’t considered experts (median of 66%).

When it comes to the decision making of scientists, a median of 55% think that scientists make judgments based solely on the facts, compared with a median of 41% who say they are just as likely to be biased as other people.

While there are often wide differences between those on the left and the right in overall trust in scientists, there are generally smaller gaps in assessments of whether scientists make decisions based on the facts and whether publics should rely more on people considered experts to solve problems.

For instance, in the UK, those on the left are 27 points more likely than those on the right to say they have a lot of trust in scientists to do what is right. However, there are quite modest differences between the shares of those on the left and right who say scientists make judgments based solely on the facts (61% and 59%, respectively) and say that the public should rely more on experts to solve problems (37% and 32%).

Where ideological differences in these two views exist, those on the left are more likely than those on the right to say that scientists make judgments on the facts and that the public should rely more on people who are considered experts. There are notable differences by ideology on these two questions in the U.S., Canada and Australia – three places where those on the left and right also express different levels of overall trust in scientists. In Australia, for instance, about two-thirds of those on the left (68%) think scientists make judgments based solely on the facts. By contrast, those on the right are about as likely to say scientists’ judgments are as likely to be biased as other people’s as to say they make judgments solely on the facts. Left-leaning Australians are also more inclined to rely on experts to solve problems; 45% of Australians on the left say the government should rely more on people who are considered experts to solve the nation’s most pressing problems compared with just 20% of those on the right.

[callout]

[callout]

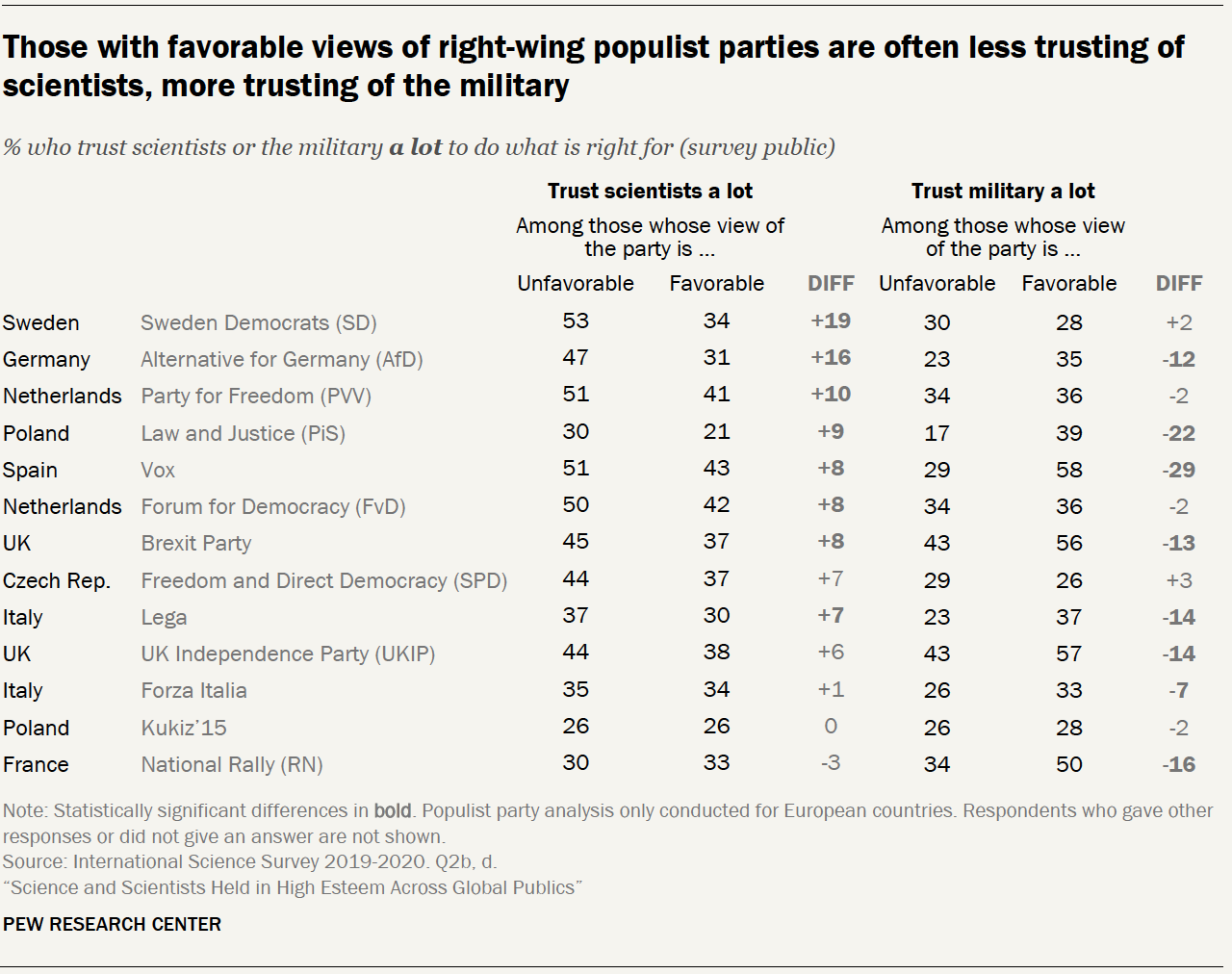

Favorable views of right-wing populist parties also tend to align with lower trust in scientists, higher trust in the military

In most places, the relationship between trust in scientists and the military and attitudes toward right-wing populist parties mirrors that seen with political ideology. People in Europe with a favorable view of right-wing populist parties tend to report lower levels of trust in scientists – and higher levels of trust in the military – than those who view these parties unfavorably. Notably, differences are less pronounced between those with favorable and unfavorable views of right-wing populist parties when it comes to whether scientists base their decisions primarily on the facts and whether the public should rely more on experts to address pressing problems. (Supporters of European populist parties stand out across a number of issues. See Center analyses from 2019 for an overview.)

[/callout]

[/callout]

Majorities say the media do a good job covering science but say the public often doesn’t know enough to understand news on scientific research

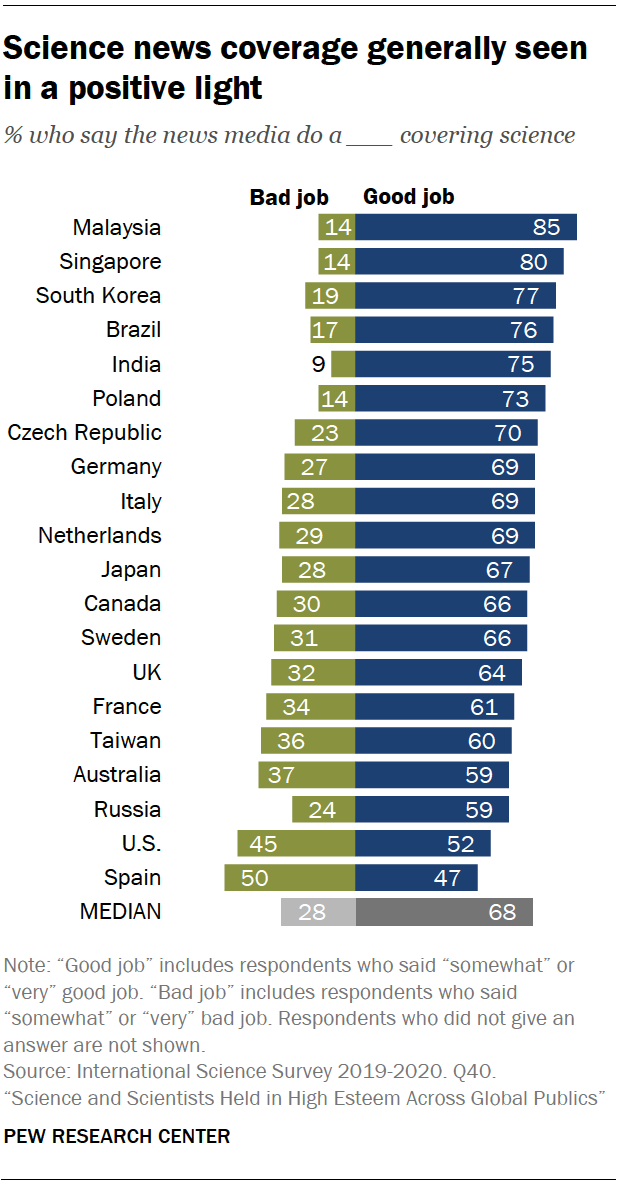

While relatively few people have strong trust in the media to do what is right, majorities across most of these publics give the news media positive marks for their science news coverage. Around two-thirds or more say the news media do a very or somewhat good job covering science topics, while far fewer say the media do a bad job covering science (20-public median of 68% vs. 28%).

While relatively few people have strong trust in the media to do what is right, majorities across most of these publics give the news media positive marks for their science news coverage. Around two-thirds or more say the news media do a very or somewhat good job covering science topics, while far fewer say the media do a bad job covering science (20-public median of 68% vs. 28%).

Malaysians are the most positive about journalists’ coverage, with 85% saying they do a good job covering science stories. About eight-in-ten in Singapore (80%) and South Korea (77%) also say the news media do a good job covering science. Ratings of the news media are lowest in the U.S. and Spain, where roughly half say the media do a good job with their science coverage.

Older adults tend to be more positive than younger adults about science media coverage. A larger share of older than younger adults say the news media do a very or somewhat good job covering science-related stories in 12 of the publics surveyed. For instance, about three-quarters of older Swedes (76%) say the news media do a good job covering science, compared with 56% of younger Swedes.

Older adults tend to be more positive than younger adults about science media coverage. A larger share of older than younger adults say the news media do a very or somewhat good job covering science-related stories in 12 of the publics surveyed. For instance, about three-quarters of older Swedes (76%) say the news media do a good job covering science, compared with 56% of younger Swedes.

People with more education are more critical of science news coverage in nine of these publics. For example, 59% of Italians with a postsecondary education or higher say the media do a good job covering science, compared with 71% of those with less education.

In most publics, political ideology – and support for right-wing populist parties – is not related to views of science media coverage. However, past Pew Research Center research has found people in a number of Western European countries who hold populist views are often less likely to trust the news media generally.

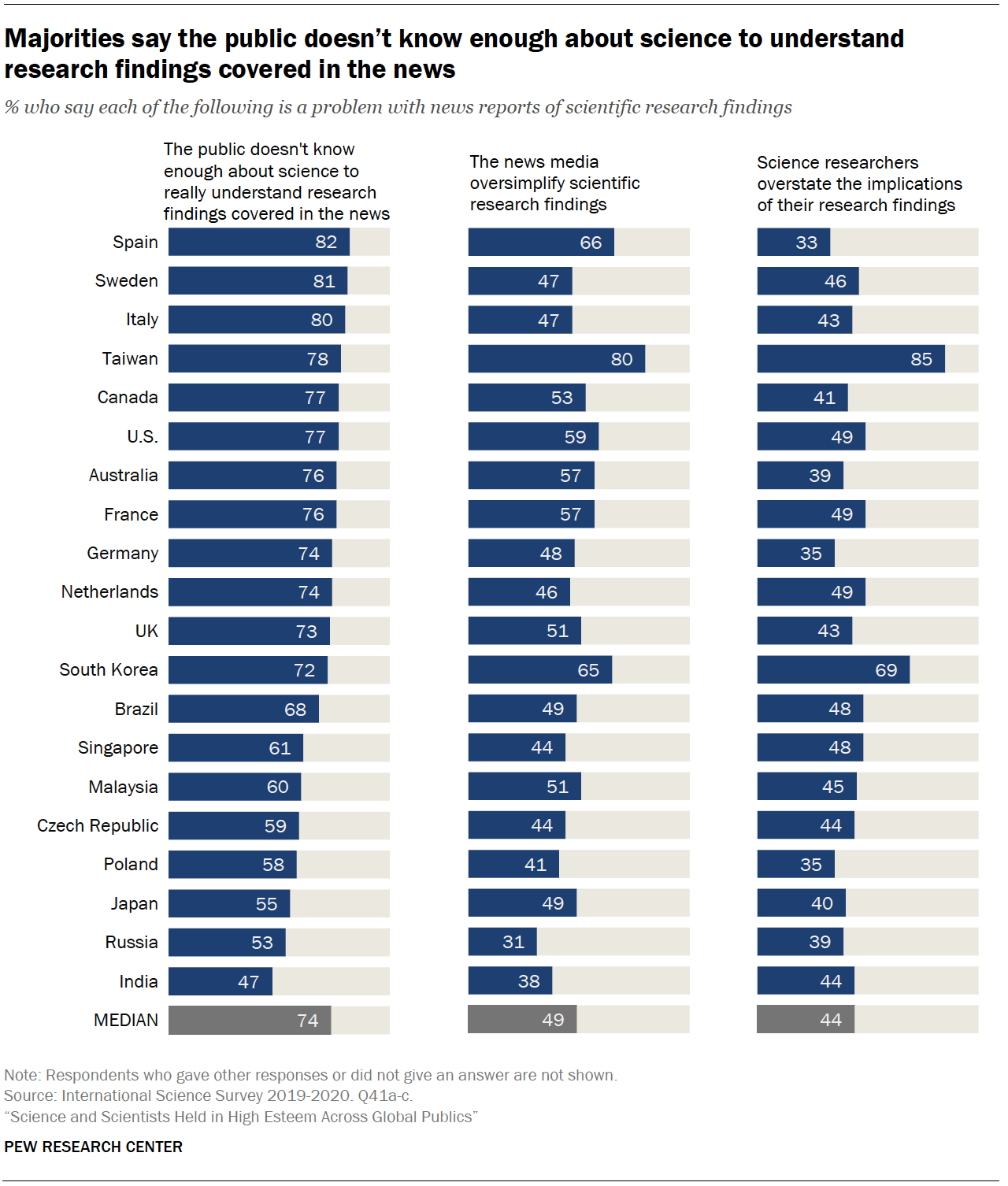

More see public understanding of science as a problem for news coverage than they do issues stemming from the media or from researchers

Asked to consider three potential problems for news coverage of scientific research, the public edict was clear. Majorities across 18 of 20 publics consider limited public understanding of science to be a problem for media coverage of scientific research (a median of 74% say this).

In general, fewer see other areas as potential problems for science news coverage. A 20-public median of 49% say the news media oversimplifying research findings is a problem in coverage. Places where a high share see oversimplification as a problem in science news coverage include Taiwan (80%), Spain (66%) and South Korea (65%).

Publics are not especially likely to blame researchers themselves for problems with science news coverage: A 20-public median of 44% say it’s a problem for science news coverage that researchers overstate the implications of their findings. Majorities in only two publics – Taiwan (85%) and South Korea (69%) – see this as a problem.

Respondents who said at least two of these three issues were problems for scientific reporting were asked a follow-up question about what they see as the biggest problem with science coverage. A lack of public understanding was most frequently seen as the biggest problem of this set: A median of 52% across publics said this. Far smaller shares said the biggest problem for coverage was media oversimplifying research findings (median of 16%) or that researchers overstate the implications of their findings (median of 13%).

People across levels of educational attainment tend to see lack of public understanding as a problem for media coverage of science. However, in nine of 20 places surveyed, those with higher levels of education are more likely to say this than those with lower levels of education. Differences by education are especially pronounced in Brazil (a difference of 25 percentage points) followed by Malaysia (an 18-point difference). People’s views about whether media oversimplification of research findings is a problem also tend to vary by education. In 11 publics, people with higher levels of education are more likely to say news media oversimplification of research findings is a problem. For details, see Appendix A.

Fact Sheets: Public Views of Science Around the World

Fact Sheets: Public Views of Science Around the World