As is the case in many world religions, rituals around death are a key part of religious practice for multiple groups in the region.

In most countries surveyed, when people are asked to consider planning a loved one’s funeral, they place great importance on religious elements. For example, 72% of Indonesians say inviting an imam or other religious leader to recite sacred texts or preach would be very important, and 78% of Thais say performing rituals at a temple or other religious site would be very important. But for most people in the region, religiously commemorating a family member’s death extends beyond the funeral: Many people also perform rituals on the death anniversary of a loved one.

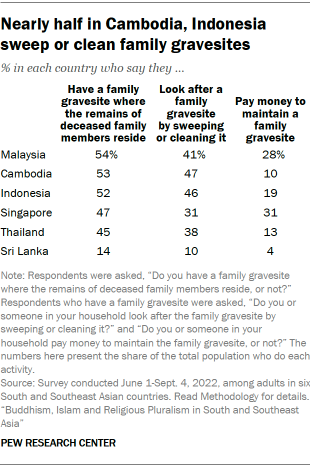

Throughout Southeast Asia, family gravesites where deceased family members’ remains reside are fairly common. Many families look after their gravesites by sweeping or cleaning them. Sri Lankans, though, are far less likely than others in the survey to have a family gravesite.

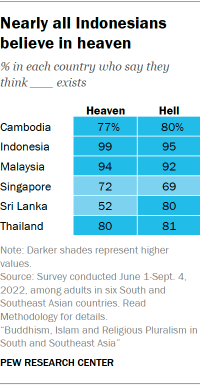

In addition to questions about funerals and gravesites, we also asked respondents to share their beliefs about the afterlife. In general, most people surveyed expressed belief in heaven and hell, including majorities in almost every religious group. Even among Singapore’s religiously unaffiliated population, roughly four-in-ten believe in each concept.

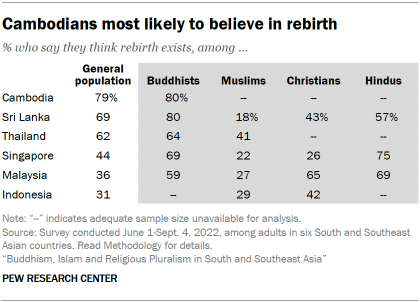

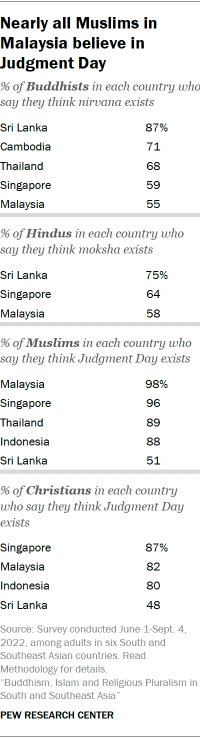

Across the countries surveyed, most Buddhists and Hindus believe in rebirth, as well as the idea that people can escape or be liberated from the cycle of rebirth (nirvana for Buddhists and moksha for Hindus). And many Muslims and Christians say they believe in Judgment Day, an end-time belief that the dead shall rise and be judged for their life’s works.

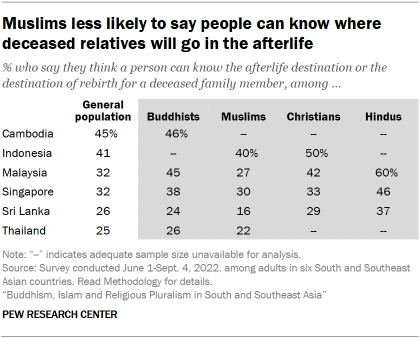

Even with such widespread beliefs in the afterlife, far fewer adults think a person can know the afterlife destination or the destination of rebirth of a deceased family member. Only among Malaysia’s Hindu community does a majority believe this is possible.

What elements are very important for a family member’s funeral?

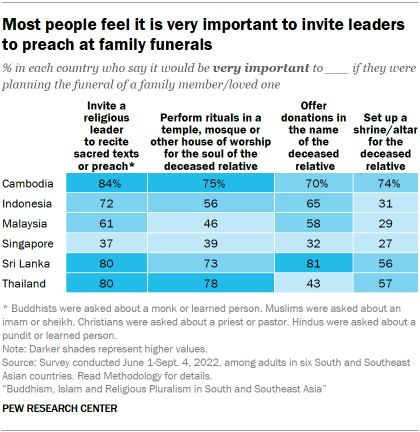

Respondents were asked how important several elements would be if they were planning the funeral of a family member or loved one. In general, inviting a religious leader, such as a monk, imam or priest, to recite sacred texts or preach is seen as very important by the largest shares of people. Majorities in every country say this, except in Singapore (37%).

Many people also say that if they were planning a loved one’s funeral, it would be crucial to perform rituals at a house of worship and to offer donations in the name of the deceased relative. In Cambodia, Indonesia and Sri Lanka, majorities say each of these funeral activities is very important.

Setting up a shrine or altar for the deceased relative is seen as less important in some countries. Still, more than half of people in the Buddhist-majority countries of Cambodia, Thailand and Sri Lanka see memorial altars as very important.15

Cambodians are among the most likely to say each of these four funeral activities is very important, while people in Singapore are consistently the least likely to say this.

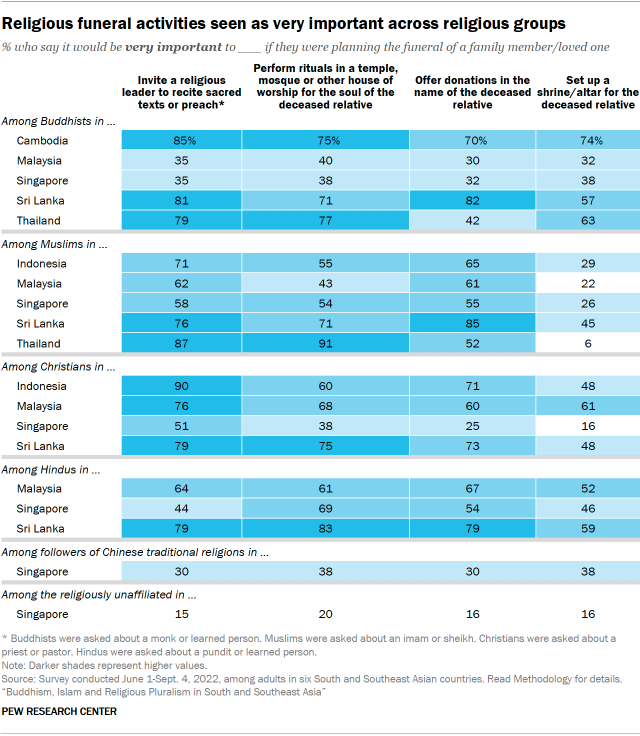

Many of these rituals are shared across religious groups. For instance, most Buddhists, Muslims, Christians and Hindus in Sri Lanka say that inviting a religious leader to recite sacred texts, performing rituals in a house of worship and offering donations are very important. But, on the whole, Buddhists and Hindus in the region are more inclined than Muslims to value a funerary altar or shrine.

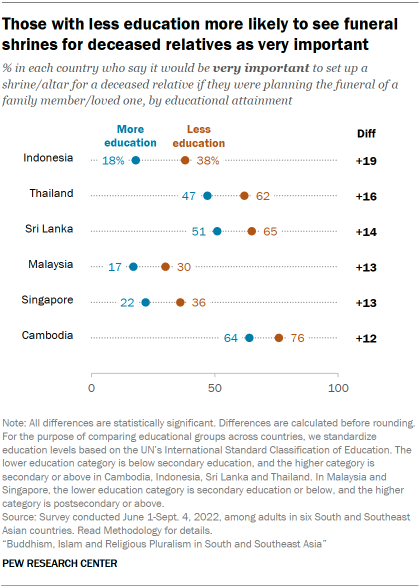

People with less formal education are more likely than others in their country to say each of the four activities would be very important for a family member’s funeral. For example, 65% of Sri Lankans who have not completed secondary school say it would be very important to set up a shrine or altar for the deceased relative if they were planning the funeral, compared with 51% of Sri Lankans with more education.

People who say religion is very important in their lives also are more inclined than others to say the four funeral activities would be very important if they were planning the funeral of a family member. For instance, 56% of Singaporeans who consider religion to be very important also say it would be very important to invite a religious leader to recite sacred texts or preach at a funeral, roughly double the share of other Singaporeans who place this much importance on the activity (26%).

Marking death anniversaries with rituals

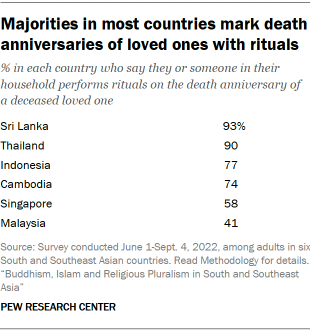

For many people in Southeast Asia and Sri Lanka, commemorating a family member’s death is not limited to the immediate time after their death. In five of the six countries surveyed, majorities say they or someone in their household performs rituals on the death anniversary of a deceased loved one, including 93% in Sri Lanka and 90% in Thailand.

Most people in nearly every religious community say their household performs death anniversary rituals. Even among Singapore’s religiously unaffiliated population, 52% say this. The only groups in which fewer than half do this are Muslims in Singapore (46%) and Malaysia (31%) and Christians in Singapore (33%).

Family gravesites

In all five of the Southeast Asian countries surveyed, people are somewhat split between those who do and do not have a family gravesite where the remains of deceased family members reside. For example, 52% of Indonesians say they have a family gravesite, while 48% do not. However, only 14% of Sri Lankans have family gravesites.

Among Buddhists, those who live in rural locations are more likely than urban dwellers to have family gravesites. In Cambodia, for instance, 57% of rural Buddhists say they have a family gravesite, versus only 44% of urban Buddhists.

Survey respondents who reported having a family gravesite were asked whether their household looks after it by sweeping or cleaning it, and separately, whether they pay money to maintain it.

Among those with a family gravesite, most say they or someone in their household sweeps or cleans the graves. Generally, people are much less likely to say they pay money to maintain the gravesites. Only in Singapore do similar shares say their household personally looks after the family gravesite and pays money to maintain it.

Belief in rebirth

Most people in the Buddhist-majority countries of Cambodia (79%), Sri Lanka (69%) and Thailand (62%) say they think people can be reborn after they die. And across the countries surveyed, majorities of Buddhists and Hindus believe in rebirth.

Muslims are the religious group least likely to believe in rebirth. In Singapore, Muslims are less likely than even religiously unaffiliated people to believe in this concept (22% vs. 32%).

Among Muslims, women are less likely than men to think that rebirth exists. For instance, 21% of Muslim women in Malaysia believe in rebirth, compared with 32% of Muslim men in the country.

Conversely, Buddhist women in the region are generally more likely than Buddhist men to hold this belief. In Cambodia, for example, 85% of Buddhist women believe in rebirth, compared with 76% of Buddhist men.

Nirvana, moksha and Judgment Day

Members of different religious communities were asked about their belief in afterlife concepts commonly associated with their tradition.

Buddhists were asked if they believe in nirvana, a term used in Buddhist teachings to refer to the state of liberation from the cycle of rebirth. While most Buddhists say they think nirvana exists, the belief is especially common in the Buddhist-majority countries of Sri Lanka (87%), Cambodia (71%) and Thailand (68%).

Hindus were asked about moksha, a concept that also commonly refers to escaping reincarnation’s cycle of rebirth. Most Hindus believe in moksha, but Sri Lankan Hindus (75%) are more likely to believe in it than are Hindus in Singapore (64%) or Malaysia (58%).

Muslims and Christians were asked if they believe in Judgment Day. This often refers to an end-time belief that the dead shall rise and be judged for their life’s works. Among the countries surveyed, Sri Lanka’s Muslims and Christians are the least likely to profess belief in Judgment Day. By contrast, Malaysian and Singaporean Muslims nearly universally think Judgment Day will happen.

Heaven and hell

Teachings about heaven and hell vary widely across the religions found in Southeast Asia and Sri Lanka. Some religions teach that heaven and hell are temporary states, while others say they are final destinations based on how people lived their lives.

In almost every country surveyed, most people believe in both heaven and hell, and the shares are usually quite similar. For example, 72% of Singaporeans think heaven exists, and 69% believe in hell.

The exception is Sri Lanka, where far fewer adults believe in heaven than in hell (52% vs. 80%). Much of this divergence is driven by Sri Lanka’s Buddhists, who are about half as likely to believe in heaven as they are to believe in hell (42% vs. 82%).

Muslims and Christians are consistently the most likely to believe in heaven. Still, majorities in almost every religious group say they think heaven exists.

In general, those who pray daily are more likely than other adults to say heaven and hell exist. In Malaysia, 97% of adults who pray daily believe in heaven, but belief in heaven falls to 80% among those who pray less often.

Women are more likely than men to believe in heaven. For example, 85% of Thai women say heaven exists, compared with 74% of Thai men. And among Buddhists, women also are more likely than men to believe in hell.

Knowing what will happen to a family member in the afterlife

Fewer than half of adults in each country surveyed think that “a person can know the afterlife destination or the destination of rebirth for a deceased family member.” People in Cambodia (45%) and Indonesia (41%) are most likely to hold this view.

Muslims generally are less likely than other adults in the countries surveyed to say that someone can know the afterlife or rebirth destination of dead family members. For instance, 27% of Malaysian Muslims take this stance, compared with 42% of Christians, 45% of Buddhists and 60% of Hindus in the country.

Among Buddhists, those who say religion is very important in their lives are slightly more likely than others to think that a person can know the afterlife destination of a deceased family member.

Is it possible to feel the presence of the deceased?

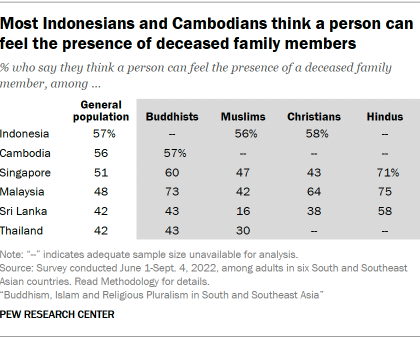

Slim majorities of adults in Indonesia and Cambodia think “a person can feel the presence of a deceased family member.” About half in Singapore and Malaysia express this view, as do slightly smaller shares in Sri Lanka and Thailand (42% each).

In general, this sentiment is especially common among Hindus in the countries surveyed. For instance, 71% of Singapore’s Hindus say a person can feel a deceased family member’s presence, compared with 60% of Buddhists, 47% of Muslims and 43% of Christians in the country. About two-thirds of Singapore’s followers of Chinese traditional religions also believe in this concept (68%).

People with less education are more inclined than adults with higher levels of schooling to think a deceased family member’s presence can be felt by the living. For example, in Indonesia, 62% of those who did not complete a secondary education take this stance, compared with 48% of adults with a secondary degree.