Across five of the six countries surveyed, virtually all respondents identify with a religion. And even in Singapore, the lone exception, about eight-in-ten adults identify with Buddhism, Christianity, Islam or another religious tradition. But for most people in the region, these religious identities are not just about religion.

Indeed, most adults who claim a religion say that their tradition (e.g., Buddhism or Islam) is not just a religion one chooses to follow, but also a family tradition one must follow, an ethnicity one is born into, or a culture one is part of. Many say their religious identity encompasses all four of these elements.

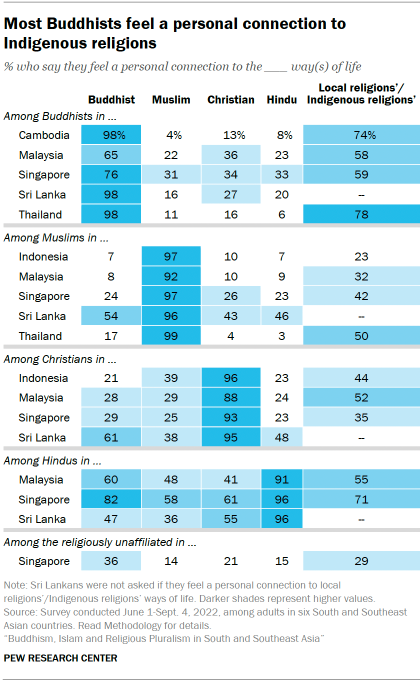

Large shares across the region also feel connections to other religions. For instance, 46% of Sri Lanka’s Muslims say they feel a personal connection to the Hindu way of life.

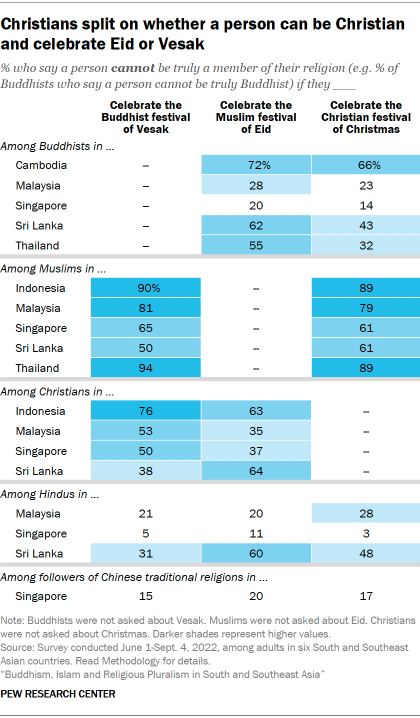

At the same time, many people say celebrating holidays or festivals associated with other religions disqualifies someone from their religious group. For example, roughly eight-in-ten Malaysian Muslims say a person cannot be Muslim if they celebrate Christmas or the Buddhist festival of Vesak.

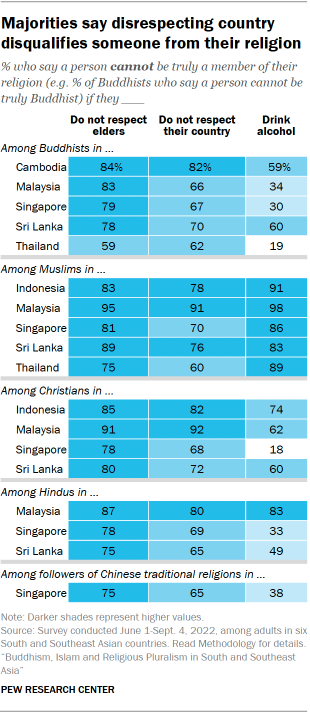

Many in the region say that holding certain beliefs or participating in religious practices is essential to being part of their group. More than eight-in-ten Christians in Singapore (87%), Indonesia (86%) and Sri Lanka (84%) say that a person cannot be Christian if they do not believe in God. The same is also said about concepts that might seem more secular. At least six-in-ten Buddhists in all countries surveyed say that a person cannot be Buddhist if they do not respect their country.

Religion, culture and ethnicity

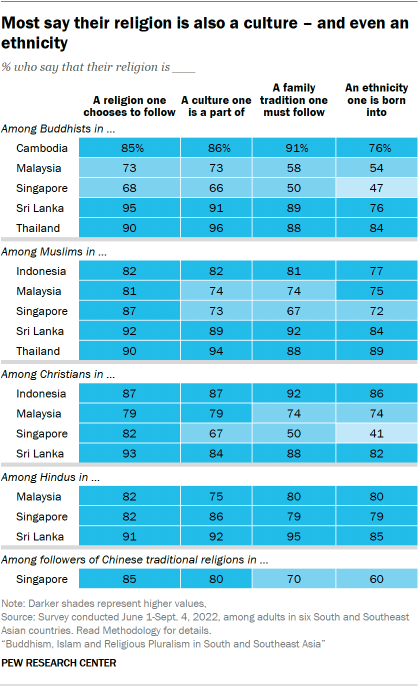

The survey asked respondents who identify with a religion whether they consider their religion to be each of the following: a family tradition one must follow, an ethnicity one is born into, a culture one is part of, and a religion one chooses to follow.

In nearly every country, majorities across religious communities say that each of these descriptions applies to their religion. For example, more than eight-in-ten Thai Muslims see Islam not only as a religion but also as a culture, a family tradition or an ethnicity.

That said, there are differences by country on these questions. Singaporeans often are the least likely to affirm the descriptions; for instance, while 50% of Singapore’s Christians say Christianity is a family tradition, far more Christians in Malaysia (74%), Sri Lanka (88%) and Indonesia (92%) say this.

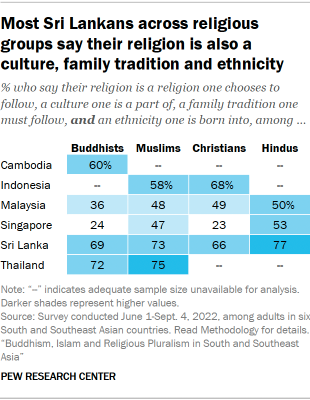

In Sri Lanka, most Buddhists, Muslims Christians and Hindus say that their religion can be described by all four statements – e.g., that Buddhism is a religion, culture, family tradition and ethnicity. The same is true for majorities of Buddhists and Muslims in Thailand, Muslims and Christians in Indonesia, and Buddhists in Cambodia.

In Malaysia and Singapore, however, no more than about half in each religious group say their religion encompasses all four dimensions. This includes Singaporeans who follow Chinese traditional religions, 35% of whom say their religious identity covers religion, culture, family tradition and ethnicity. And one-in-ten of Singapore’s Buddhists say Buddhism is about none of the categories measured in the survey.

Personal connections to other religions

Despite these deeply rooted religious identities, in this religiously diverse region it is also common for people to feel a personal connection to at least one religion other than the one they identify with. For example, at least four-in-ten Sri Lankan Muslims say they feel “a personal connection” to the Buddhist (54%), Christian (43%) and Hindu (46%) “ways of life.”

On balance, Muslims and Buddhists are among the least likely to say that they feel an affinity toward other religions, whereas Christians and Hindus – religious minority groups throughout the countries surveyed – are somewhat more likely to say they have a personal connection to other ways of life.

Additionally, roughly a quarter or more in every group say that they have a personal connection to the local religions’ ways of life in their country. This includes at least seven-in-ten Buddhists in Thailand (78%) and Cambodia (74%), and a similar share of Hindus in Singapore (71%).

Unsurprisingly, nearly all who are religiously affiliated say they feel a personal connection to their own religion, such as the 98% of Cambodian Buddhists who feel connected to the Buddhist way of life and the 96% of Indonesian Christians who say the same about Christianity. Buddhists in Malaysia and Singapore are less likely to feel personally connected to the Buddhist way of life, although most still feel this way (65% and 76%, respectively).

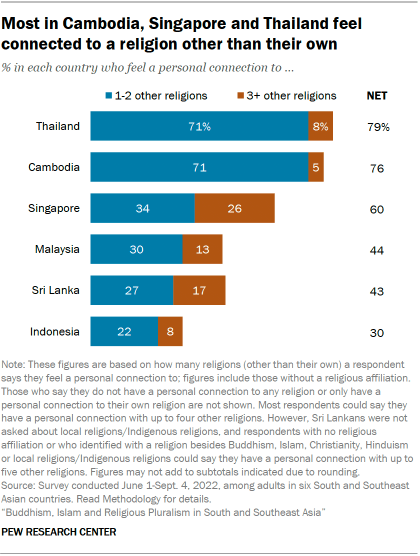

Fewer than half of people in Indonesia, Malaysia and Sri Lanka say they feel a personal connection to a religion besides their own. By contrast, majorities in Cambodia, Singapore and Thailand feel a connection to at least one religion outside their own, even though these countries differ drastically in their religious makeup.

In Singapore, one of the most religiously diverse countries in the world, 26% of respondents feel a personal connection to at least three religions they do not identify with, while 34% feel connected to one or two other faiths. And while 96% of Cambodian adults identify with Buddhism, about three-quarters also say they feel personally connected to another religion, many of them to local Cambodian religions – which could include animism.

Differences between those with and without personal connections to a religion

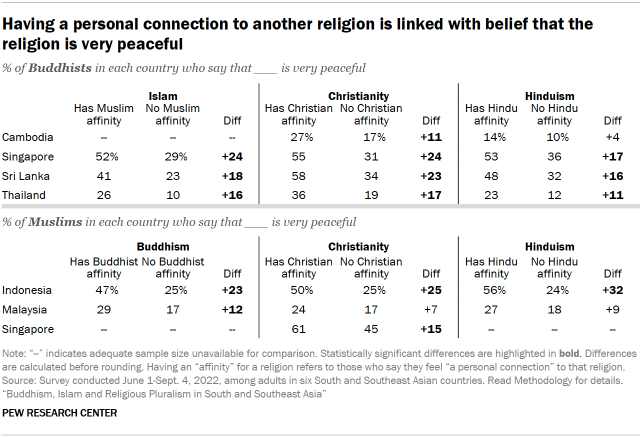

On balance, people who say they have a personal connection with a religion besides their own express more tolerant views of that religion. They are more likely to think the religion is very peaceful, to be willing to accept members of that religion as neighbors, and to say the religion is compatible with their country’s values and culture.

For example, Sri Lankan Buddhists who say they have a personal connection to Islam are more likely than those who do not have this connection to say that Islam is very peaceful (41% vs. 23%). Similarly, Malaysian Muslims who feel a personal connection to Buddhism are more likely than other Malaysian Muslims to say that Buddhism is very peaceful (29% vs. 17%).

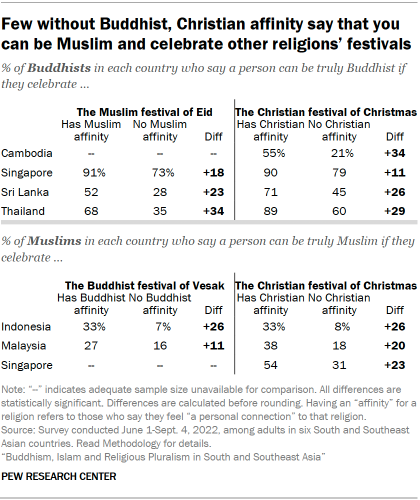

Additionally, people who say they have a personal connection to another religion are more likely to say someone can celebrate that religion’s holiday while still remaining a member of their own religious community. For example, in Malaysia, 38% of Muslims who have a personal connection to Christianity say that a person can be truly Muslim if they celebrate Christmas; only 18% of Malaysian Muslims who do not have this personal connection say the same.

Personal connections with other religions also increase the likelihood that someone prays or offers their respect to that religion’s deities or founder figures. For instance, 77% of Sri Lankan Buddhists who have a personal connection to Hinduism say they pray or offer their respects to Shiva, compared with 59% of other Sri Lankan Buddhists. And among religiously unaffiliated Singaporeans who feel personally connected to Christianity, 38% pray or offer respects to Jesus Christ – far more than among others in Singapore’s religiously unaffiliated community (11%).

What disqualifies someone from a religious group?

The survey asked respondents if a person can still be a member of their religious group under a variety of conditions – such as if they don’t participate in religious practices that are traditionally associated with their religion, or if they partake in specific religious practices associated with other religions.

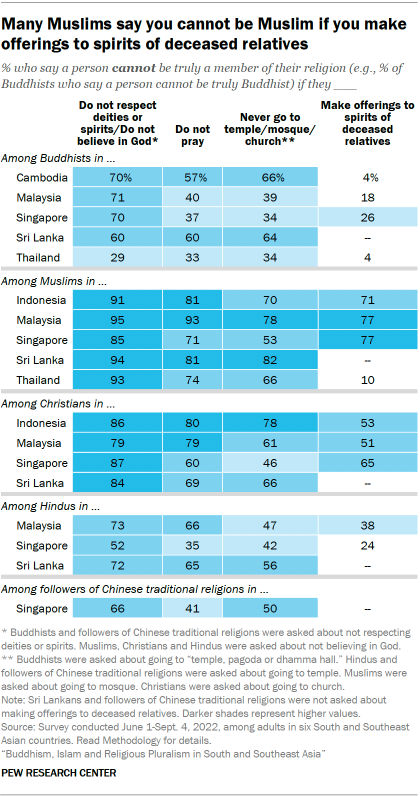

Muslims and Christians generally are more likely than Buddhists to say one must pray or attend a house of worship to be a member of their group. And they’re more likely than Buddhists to say that making offerings to deceased ancestors’ spirits disqualifies someone from their religion.

In four of five countries, most Buddhists say not respecting deities and spirits disqualifies someone from being Buddhist. Muslims, Christians and Hindus received a different question, with most saying that not believing in God is incompatible with being Muslim, Christian or Hindu. In Singapore, though, only 52% of Hindus take this view.

Most Muslims in the region say that a person cannot be Muslim if they celebrate Christmas or the Buddhist festival of Vesak. But among Buddhists and Christians, opinions vary about whether participating in other religions’ holidays is compatible with their religion. For instance, most Christians in Sri Lanka (64%) and Indonesia (63%) say a person cannot be Christian if they celebrate Eid, but far fewer Christians in Malaysia (35%) and Singapore (37%) take this view.

On balance, Hindus are open to fellow Hindus celebrating non-Hindu religious festivals. In Malaysia, only 28% of Hindus say celebrating Christmas disqualifies someone from being Hindu.

Majorities among all religious groups say that a person cannot be a member of their religion if they disrespect either elders or their own country.

Views on drinking alcohol, however, are more mixed, even within some religious groups across the region. For example, about six-in-ten Buddhists in Cambodia and Sri Lanka say drinking alcohol disqualifies someone from being Buddhist, but just 19% of Thai Buddhists say the same. Overwhelming shares of Muslims in every country surveyed, meanwhile, say that a person cannot be Muslim if they drink.

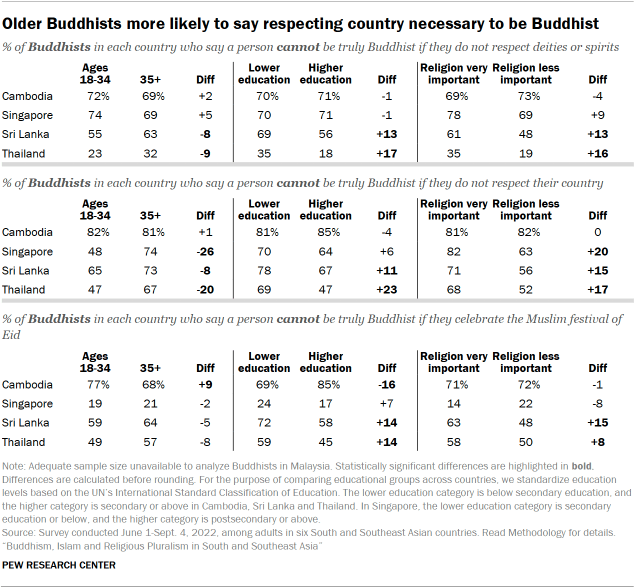

Older Buddhists are somewhat more likely to say that a person cannot be Buddhist if they disrespect their country. For example, 74% of Singaporean Buddhists ages 35 and older say that a person cannot be Buddhist if they disrespect Singapore, compared with 48% of younger Buddhist adults.

There are other patterns among Buddhists on questions about Buddhist identity. Buddhists who say religion is very important in their lives and have a lower education are, on the whole, more inclined to view certain behaviors as disqualifying. For example, Buddhists with lower levels of education in Sri Lanka and Thailand are more likely than Buddhists with more education in those countries to say a person cannot be Buddhist if they disrespect deities or spirits or if they celebrate Eid.

Cambodia sometimes stands out from these general patterns; Cambodian Buddhists with more education are especially likely to view Eid celebrations as disqualifying in Buddhism.