The Rev. Miniard Culpepper, pastor of Pleasant Hill Missionary Baptist Church, preaches next to an image of George Floyd in June 2020 in Boston. (Pat Greenhouse/The Boston Globe via Getty Images)

This analysis is based on the texts of 12,832 sermons shared online by 2,143 U.S. religious congregations (nearly all of them Christian churches) delivered between Aug. 31 and Nov. 8, 2020 – a period that included the 2020 U.S. presidential election on Nov. 3 and the Sunday following Election Day. The dataset includes sermons from 438 evangelical Protestant congregations, 388 mainline Protestant congregations, 235 Catholic parishes and 205 historically Black Protestant congregations. The remaining congregations could not be reliably classified, belong to other Christian traditions (such as Orthodox Christian denominations) or belong to other faiths. While we collected sermons from a sample of congregations in our database, all sermons found on those websites were included in the analysis.

After identifying a comprehensive list of websites of U.S. churches using the Google Places API, we deployed a custom-built web scraper to navigate through each church’s website, find any pages with sermons (in audio, video or text form), download each sermon along with the date on which it was delivered, and transcribe it from audio to text, if necessary. We then developed a machine learning classifier to identify sermons that discussed certain key topics – including the election, the COVID-19 pandemic and racism in America.

For technical and legal reasons, the Center was largely unable to collect sermons that were not posted or embedded directly on a church website. In particular, sermons shared or streamed solely on church Facebook accounts could not be included in this research. Sermons shared on YouTube accounts also were not included, unless they were embedded directly on the church’s own website.

See Appendix A for more details on how the congregations included in this study differ from congregations nationwide. See the Methodology for additional technical information on how this study was conducted.

Religious belief is key to many Americans’ political identities, but the public is divided on whether clergy should preach about politics from the pulpit. So, when pastors across the country addressed their flocks last fall, how did they discuss an election that many Americans viewed as historically important?

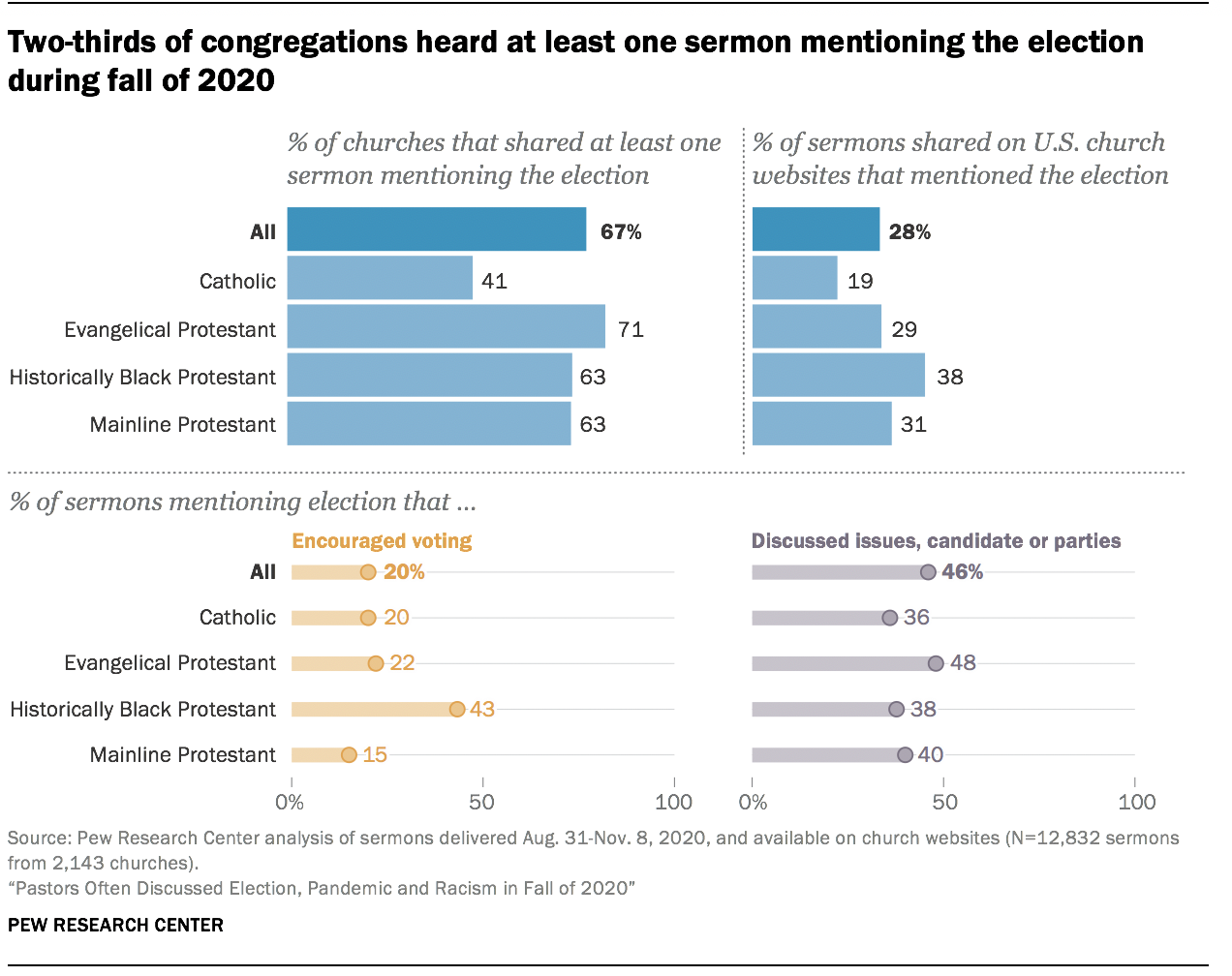

A new Pew Research Center analysis finds that among churches that posted their sermons, homilies or worship services online between Aug. 31 and Nov. 8, 2020, two-thirds posted at least one message from the pulpit mentioning the election. But these rates varied considerably among the four major Christian groups included in the analysis: 41% of Catholic congregations in the database heard at least one sermon mentioning the election, compared with 63% of both mainline Protestant and historically Black Protestant congregations and 71% of evangelical Protestant congregations.

Definitions and analytic frames used in this report

U.S. churches vary widely in the structure of their services and how much of those services they post online. Some post just the sermon. Others post the sermon and part of the service. Still others post the entire service. In many cases, the beginning and end of a sermon are not clearly labeled in the text, audio or video files on a church’s website. As a result, the automated tools used for this analysis cannot isolate sermons from other elements of religious services with precision.

In this report, an “online sermon” refers to a portion of a religious service posted on a church website that contains a commentary from the pulpit but sometimes may include other parts of the service as well.

This report also uses two different frames for comparison, depending on the focus of the analysis. Some findings are based on the share of all sermons that have certain characteristics (e.g., “28% of sermons delivered during the study period referenced the election”). Other findings are based on the share of all congregations that heard discussion of a topic in any of their sermons (e.g., “67% of all congregations heard at least one sermon mentioning the election during the study period”).

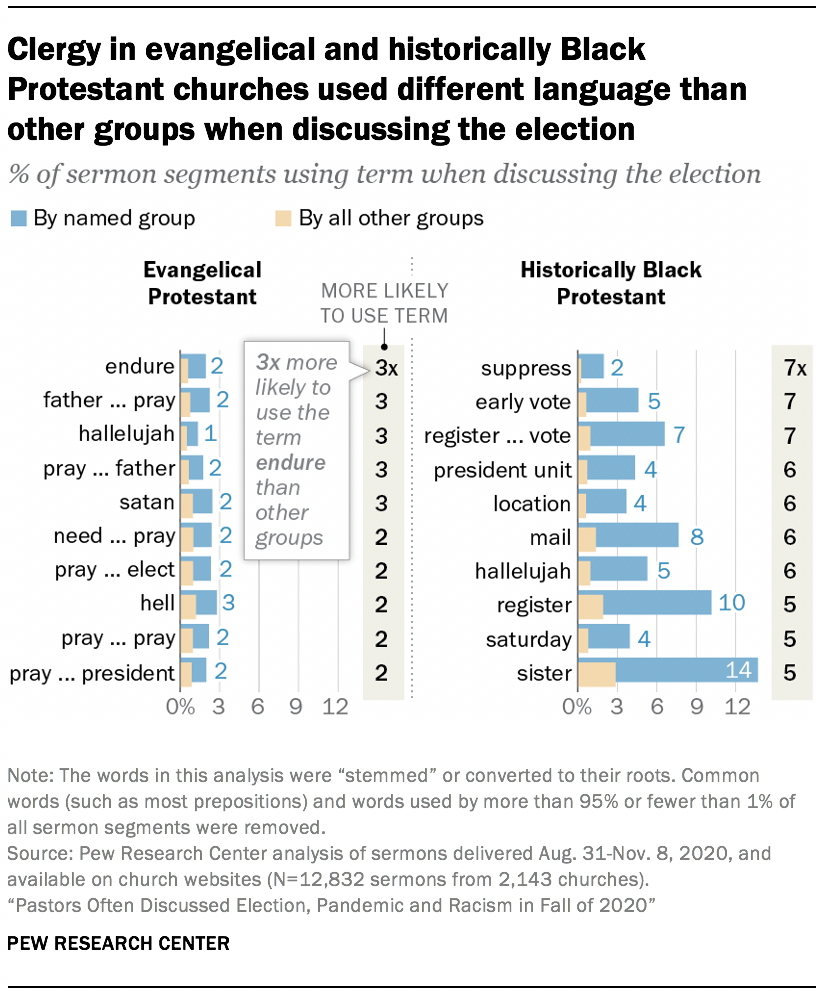

Moreover, the content of the messages tended to differ. Roughly half of all evangelical Protestant sermons mentioning the election discussed specific issues, parties or candidates (48%), the highest share among the four major Christian groups. And, in discussing the election, evangelical pastors tended to employ language related to evil and punishment at a greater rate, using words and phrases such as “Satan” or “hell” at least twice as often as other clergy did. Evangelical pastors also were more likely to use the phrase “pray [for our] president” when discussing the election.

By contrast, historically Black Protestant pastors were by far the most likely to encourage voting and voter turnout: 43% of historically Black Protestant sermons mentioning the election either explicitly encouraged voting or discussed the election in a manner that assumed listeners would vote, roughly double the share of any other group. And when historically Black Protestant pastors discussed the election, they tended to use words or phrases related to voting or voter rights – such as “suppress[ion],” “early voting” and “register [to] vote” – more often than pastors from other groups.

Although most congregations posted at least one sermon mentioning the election at some point during the study period, relatively few pastors openly stumped for particular candidates or parties. Indeed, explicit endorsements from the pulpit were rare enough that researchers could not develop a machine learning model that would reliably identify such language across all sermons in the database. However, in a sample of 535 sermons mentioning the election that researchers examined while attempting to train such a model, 61 seemed clearly to favor either Republicans or Democrats, even if they did not mention parties or candidates by name.

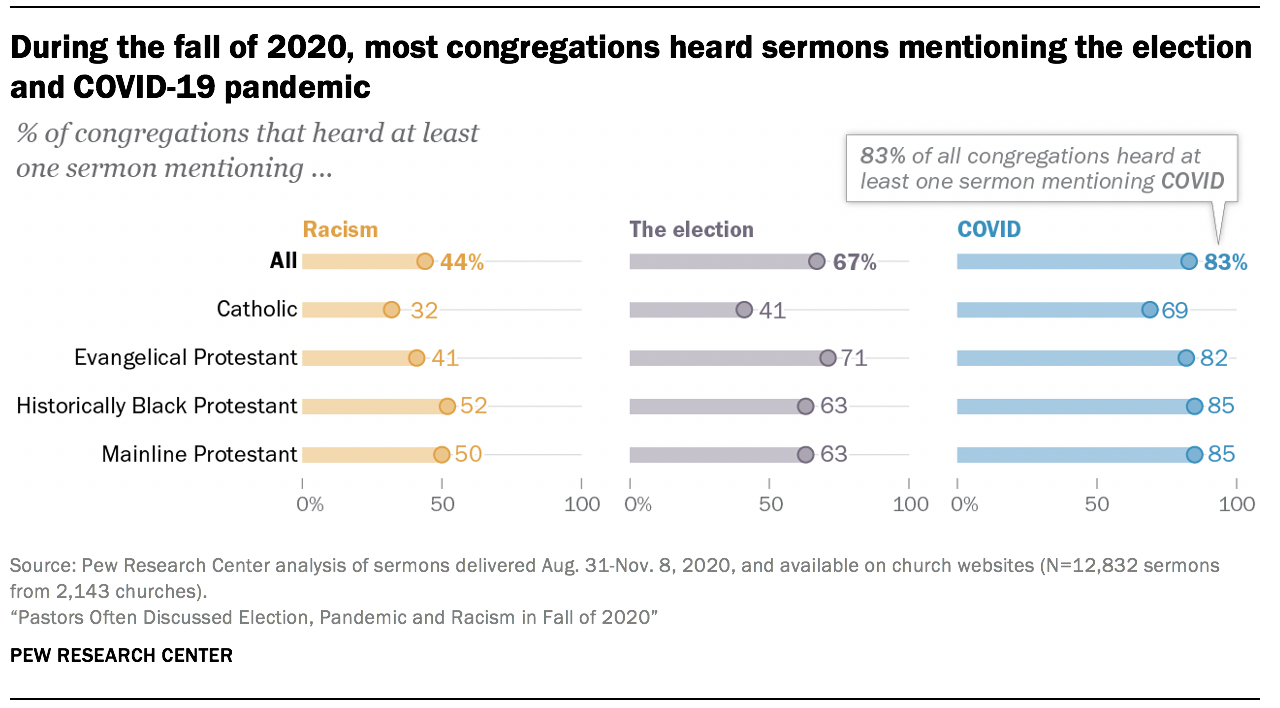

Pastors also discussed other prominent issues during the period. About eight-in-ten congregations in the database (83%) heard at least one sermon touching on the COVID-19 pandemic, while 44% heard at least one reference to racism in America. Catholic congregations stood out as the least likely to mention any of the topics analyzed in this study during the services or homilies they shared online.

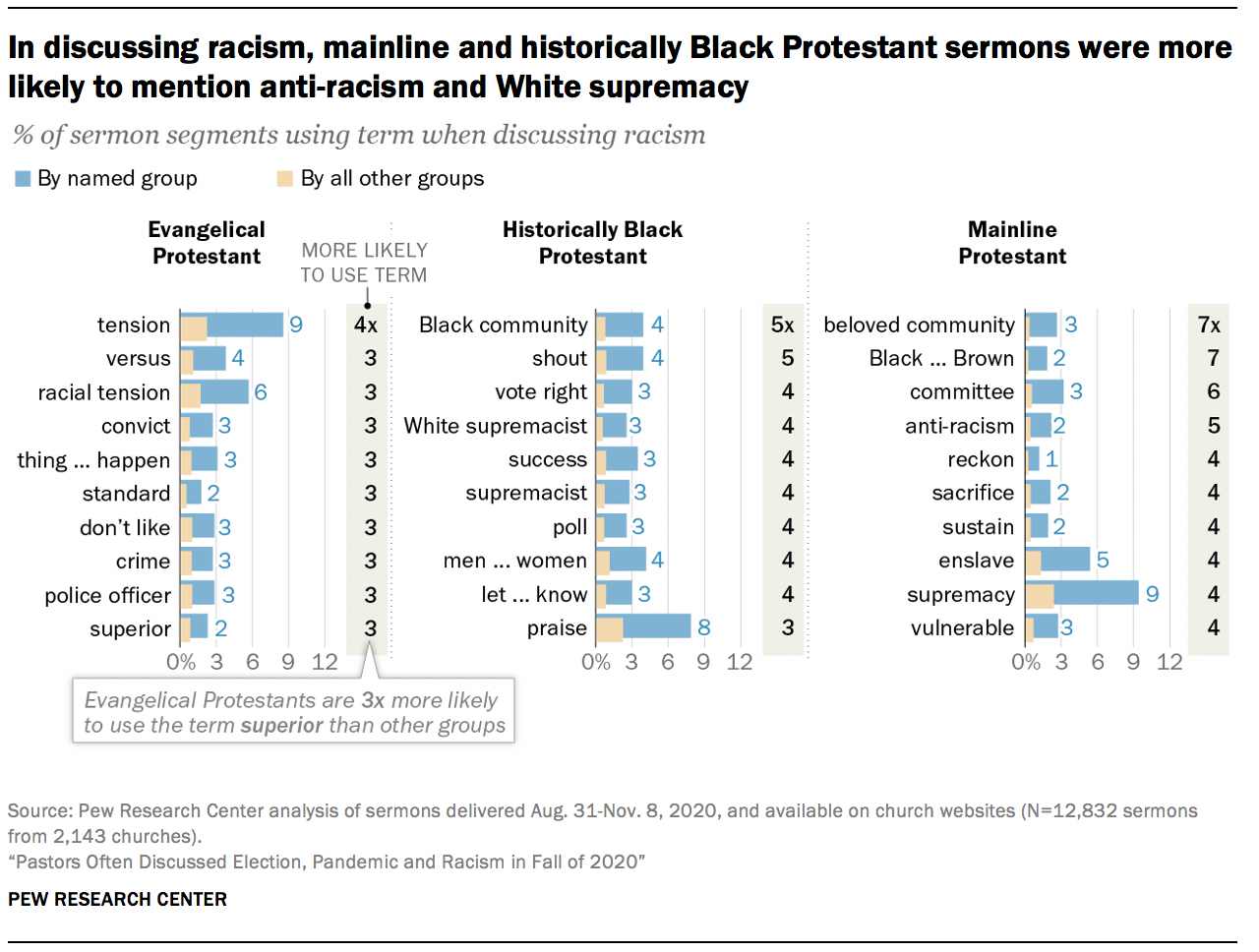

In discussing racism in America, evangelical pastors disproportionately used oblique phrases such as “racial tension.” Meanwhile, clergy in mainline Protestant and historically Black Protestant congregations tended to discuss this issue using more direct terms like “anti-racism” and “White supremacist.”

These are among the main findings of an analysis of 12,832 sermons, homilies or full services delivered to 2,143 American congregations between Aug. 30 and Nov. 8, 2020 – a period when many congregations were streaming their services online due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This study builds on an earlier Center report, which examined sermons shared online in mid-2019.

It is important to note that the sermons included in this dataset are not necessarily representative of the messages delivered in all U.S. religious congregations, for a variety of reasons. First, this analysis focuses on Christian churches and does not include other religious traditions. Moreover, not all Christian churches make their sermons publicly available online – and those that do place their sermons online may choose selectively, posting some but not others. Nonetheless, the sermons database provides a window into what churchgoing Americans heard in the pews – physical or virtual – during a historic moment in American civic life.

A majority of churches shared or livestreamed sermons discussing the election and COVID-19 pandemic during the fall of 2020

The 2020 election, the COVID-19 pandemic and nationwide protests over systemic racism and police violence against Black Americans dominated news cycles in the latter half of 2020. This analysis finds that they featured prominently in U.S. sermons as well. (See the Center’s topic pages for more on the 2020 election and the COVID-19 pandemic.)

A majority of congregations included in this study heard at least one sermon mentioning the COVID-19 pandemic (83%) or the 2020 election (67%). And a substantial minority of congregations (44%) heard at least some discussion of racism in America. Still, pastors of different religious traditions discussed each topic at different rates.

For instance, mainline Protestant and historically Black Protestant congregations were more likely than evangelical Protestant or Catholic congregations to hear discussion of racism from the pulpit during this time period. Conversely, evangelical churchgoers were the most likely to hear discussion of the election.

Catholic priests were consistently the least likely to mention any of these three issues in their sermons, homilies or services shared online. Fewer than half of Catholic congregations in the database heard a single mention of the election (41%) or racism (32%) during the 10-week study period. And although 69% of Catholic congregations heard at least one mention of the pandemic, congregations belonging to the other three major Christian traditions were at least 10 percentage points more likely to hear messages from the pulpit about the coronavirus.

Pastors often mentioned these topics multiple times in the same sermon

To better understand how heavily pastors focused on each topic, researchers broke each sermon down into smaller segments of 250 words each (the median sermon in this collection had 26 such segments, and a segment of that length often occupied one to two minutes of speaking time). The research team then used a combination of labeling by human coders and statistical modeling to determine how many of these individual segments mentioned the three major topics examined in this study.

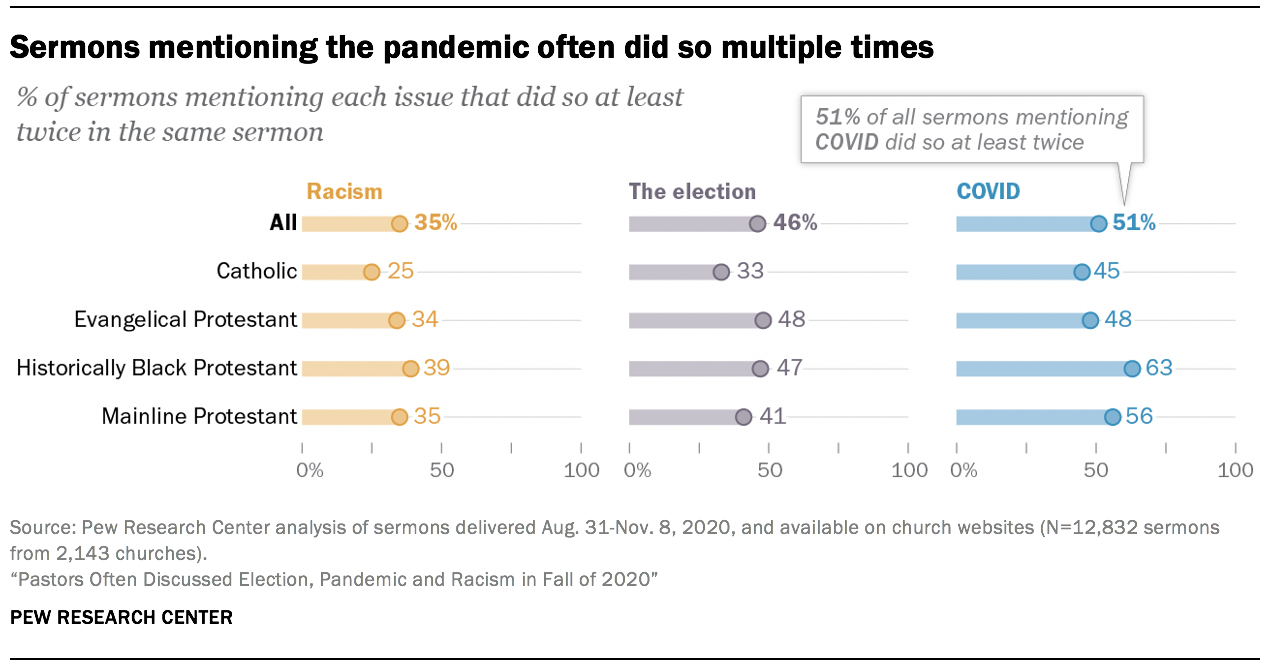

Using a similar technique on a set of sermons delivered in the spring of 2019, the Center found that when pastors discussed abortion, they tended to do so only glancingly. Just one-quarter of all sermons that mentioned abortion did so in more than one 250-word segment.

In contrast, pastors tended to mention the topics examined in this study with greater regularity. Some 35% of sermons where the pastor discussed racism – and 46% of those that mentioned the election – did so in at least two separate 250-word segments.

Pastors were particularly likely to discuss the COVID-19 pandemic at some length: 51% of sermons mentioning this topic included references to the pandemic in two or more 250-word segments. And certain groups were especially likely to make the pandemic a recurring theme in their services. Some 56% of sermons by pastors in mainline Protestant churches that mentioned the pandemic (and 63% of those by pastors in historically Black Protestant churches) did so at least twice.

Nearly half of election-related sermons discussed specific issues, candidates or parties; one-in-five encouraged voting

Researchers also assessed what share of sermons discussing the election encouraged listeners to vote, as well as what share discussed specific issues, candidates or political parties. (The Supreme Court, abortion or taxes would all be examples of an issue). Among the 28% of sermons that discussed the election, roughly half (46%) discussed specific issues, parties or political candidates while 20% encouraged listeners to vote. (For more on how we identified these topics, see the Methodology.) Translated to the congregational level, this means that 23% of all congregations in the database heard at least one sermon during the fall of 2020 encouraging them to vote, while 43% heard at least one discussing parties, issues or candidates.

Researchers also attempted to identify instances in which pastors openly encouraged their congregants to vote for a specific party or candidate. However, such explicit admonitions were rare and, as a result, the Center was unable to systematically identify them across the database. But among a sample of 535 segments of sermons that discussed the election, researchers labeled 35 as advocating for Republicans and 26 as advocating for Democrats. This included some cases in which pastors named a candidate or party as well as cases in which they advocated a clearly partisan array of policy positions.

Predictably, political discussions reached a crescendo during the week of the election. Although 28% of all sermons delivered over the entirety of the study period mentioned the election in some way, that share rose to 49% of all sermons delivered in the first week of November – including 61% of sermons given that week in historically Black Protestant congregations. Also, it appears that sermons mentioning the election were, on the whole, as likely as other sermons to have some scriptural framing. Fully 96% of all sermons that touched on the election mentioned at least one book of the Bible by name, compared with 95% of sermons that did not mention the election.

Different Christian groups used distinctive terminology when discussing the election

To better understand the tenor of what congregants heard in sermons during the fall of 2020, researchers analyzed the words that pastors of each group used most disproportionately – relative to other Christian groups – when discussing topics such as the election. In discussing the election, evangelical pastors were disproportionately likely to use the words “Satan” and “hell,” while historically Black Protestant pastors focused heavily on voter turnout and registration.

To conduct this analysis, the research team first identified all the 250-word segments from a given Christian group that discussed a topic – for instance, all segments of evangelical Protestant sermons that mentioned the election.

Next, we calculated the share of those segments that used a certain word or phrase. Finally, we calculated that same value for all the sermon segments of other groups that discussed the same topic, and we divided the former by the latter. This statistic represents how many times more often a word or phrase appears when pastors in one Christian tradition discuss a topic relative to when pastors in the other Christian traditions discuss that same topic. Common conjunctions, prepositions and articles (such as and, but, of, in, to, from, a, the) were removed for this analysis, and many words were reduced to their roots. For example, the words “election” and “elected” would be reduced to “elect-.” In performing this analysis, researchers also removed any words or phrases used in fewer than 1% of all segments.

While the preceding section of this report examined the prevalence of broad topics within sermons as a whole, this analysis focuses on the short (250-word) segments of sermons that contain pertinent mentions of those topics. This focus is necessary because most Christian services contain core elements – such as traditional prayers, a reading from scripture or the giving of communion – that are far more statistically distinct from other groups’ services than any differences in how they discuss a topic like politics. Focusing on the short segments that mention the election removed many of these liturgical elements, allowing other differences to become apparent.

When discussing election, evangelical pastors disproportionately mentioned ‘hell’ and ‘Satan’; pastors in historically Black churches more likely than others to urge voting

When pastors in evangelical Protestant congregations discussed the election, they disproportionately used phrases related to prayer and to forces of evil. Six of the 10 most distinctive terms in their sermons included the word “pray,” including variations of the phrase “pray … president” such as “pray for our president” or “pray for the president.” Sermons in evangelical congregations also disproportionately used terms such as “Satan” or “hell” when discussing the election.

It is important to note that even though these terms were distinctive to evangelical sermons mentioning the election, they were not especially common in evangelical sermons. The 10 most distinctive terms in evangelical sermons discussing the election were all used in fewer than 5% of segments discussing the election.

By contrast, historically Black Protestant pastors disproportionately used words related to voter suppression, registration and turnout. The word “suppress” (along with common variants such as “suppressed” or “suppression”) was the single most distinctive term used by pastors in historically Black Protestant churches when discussing the election. They also urged their congregations to vote, using words and phrases like “early voting,” “mail” and “register … vote.” Further, some of these phrases were fairly common. For instance, historically Black protestant pastors used the word “register” in 10% of segments that mentioned the election.

By contrast, historically Black Protestant pastors disproportionately used words related to voter suppression, registration and turnout. The word “suppress” (along with common variants such as “suppressed” or “suppression”) was the single most distinctive term used by pastors in historically Black Protestant churches when discussing the election. They also urged their congregations to vote, using words and phrases like “early voting,” “mail” and “register … vote.” Further, some of these phrases were fairly common. For instance, historically Black protestant pastors used the word “register” in 10% of segments that mentioned the election.

Catholic and mainline Protestant sermons touching on the election, by comparison, were primarily distinguished by language related to their respective religious practices – for instance, “Mass,” “bishop” and the word “Catholic” in Catholic sermons, and “communion” in mainline Protestant sermons. This indicates that although these groups may have used some distinguishing language in discussing the election, that language was less distinctive than the usual hallmarks of a Catholic or mainline Protestant service.

Direct quotes from sermons discussing politics and the 2020 election

“We also established that anytime we endeavor to rebuild like the Israelites, we will discover that we will face opposition. For them, opposition came in the form of a Samaritan named Sanballat and others like Tobiah, who tried to keep them from rebuilding. For us, opposition comes in the form of voter suppression, voter intimidation, systemic injustice and a president whose tyrannical leadership chips away at our democracy on a daily basis.” – Historically Black Protestant sermon

“If all lives matter and individual lives matter, then there’s no such thing as being pro-abortion, no such thing as being pro racism, or ignoring human trafficking, or discrimination or prejudice. Those are the things that, if all lives matter, should be our priority, right? Therefore, I would encourage everyone: You need to vote biblical morality and values, if all life matters.” – Evangelical Protestant sermon

“Perhaps, then, today we need to look beyond the chaos of Tuesday’s election and settle instead on the overreaching truth of our lives on Earth. That is what St. Paul told the Thessalonians: ‘Thus we shall always be with the Lord. Therefore, console one another with these words.’ So dead or alive, we are always with the Lord in the Gospel. Today, we are reminded to be ready for anything in life, to be a people prepared not only to deal with the pandemic and a messed up presidential election, but to remember that we are to follow on the path of those wise virgins. To have not only our own lamps lit, but to have extra oil with us just in case. Like it or not, we need to be prepared to meet the Lord when he does call us home.” – Catholic sermon

“We simplify everything as if all these complex issues could be boiled down into a right and a wrong. It’s preposterous. And then we define each other by these absurd categories that we have created, and what happens is, we don’t know each other anymore. We’re defined by labels instead of seeing each other as human beings, and we stop listening. And that, my friends, can get very dangerous as this election approaches. If we define each other solely by our politics and our slogans and our words, we cease to listen to one another, and we are in danger of becoming just like the scribes and the elders and the Pharisees. So I ask you: Don’t give me any words. I don’t want to hear a slogan. But do tell me this: Do you serve the less fortunate than you? Do you take time out of your life to help those in need, to do something that is solely not for you, but for someone else?” – Mainline Protestant sermon

Quotations have been lightly edited for readability.

In discussing racism in America, mainline Protestant clergy urged anti-racism, while clergy in historically Black Protestant churches discussed voting and White supremacy

These groups also used distinctive language to discuss racism in America. Pastors in mainline and historically Black Protestant congregations tended to address racism and racial justice directly. For instance, the most distinctive terms used by mainline Protestant pastors included “supremacy” and “anti-racism,” and the most distinctive terms used by Black Protestant clergy included phrases like “White supremacist” and “Black community.”

Evangelical pastors, by comparison, often used more oblique language to describe racism. Terms such as “tension” and “racial tension” are among the most distinctive terms in evangelical sermons mentioning racism in America. Evangelicals also used terms like “police officer,” “crime” and “convict” about three times as often as other pastors when discussing racism.

Catholic sermons were once again distinguished by words common to Catholic homilies or services such as “[Pope] Francis” or “Bishop.” For a full list of each group’s most distinctive terms, see Appendix B.

Direct quotes from sermons discussing racism in America

“I don’t know when in the world Black lives are gonna matter to some White people, and I don’t know why they love Black culture but can’t stand some of the Black people. I don’t know why Black women who have literally given everything to this world still can’t find a safe space for them to grow, nourish and flourish, or even live. And since I know I already jumped out there, can I just tell you how I’m really feeling? I don’t know how it’s possible for there to have been a $12 million wrongful death lawsuit that was settled, but have nobody responsible for the death. I don’t know how sheetrock could get more justice than one of our beautiful Black sisters. And I don’t know how many more miscarriages of justice we will have to endure before Black people give birth to a response that might turn this country upside down.” – Historically Black Protestant sermon

“Our original sin, then, according to critical race theory, is whiteness. … Salvation from that fall begins when the oppressors become woke – you heard that term, ‘woke’ recently? This is what’s going on in the NFL, and that’s why I won’t be watching it. When they see and repent from their own sins as oppressors and begin to dismantle the inherently oppressive structures of their culture, they’re woke. In other words, you destroy your country’s history, you tear down all the the statues of White people. And since Whites can’t see their own racism, according to the CRT [critical race theory], they need to learn to see the world through the CRT lens. Only then will racial equality be possible. For CRT, then, salvation comes through law, not grace. Forgiveness only comes after complete and ongoing capitulation. Ultimately, CRT is rooted in a blend of two worldviews: Marxism – the oppressed and the oppressor – and secular humanism – the belief that humanity is capable of self-fulfillment and rescue by self-effort apart from God. However, once God is removed, so is any objective standard defining what it means to live a fulfilled, moral life.” – Evangelical Protestant sermon

“The murder of George Floyd has blown open the terrible evil of individual and institutional racism that serves the dominant culture so well. Whether blatant or hiding menacingly under the surface, Roxane Gay wrote that we Blacks live with the knowledge that a hashtag is not a vaccine for White supremacy. We live with the knowledge that, still, no one is coming to save us. The rest of the world yearns to get back to normal. For Black people, normal is the very thing from which we yearn to be free.” – Catholic sermon

“But we have to understand that we are called. There is work to be done. We are called to begin that healing. We’re called to begin that healing. The way that we overcome systemic racism, the way we overcome systemic poverty, we overcome Bible abuse against homosexuals and queer people, the way we overcome transphobia and sexism, the way we overcome people who don’t have a living wage because of the color of their skin or the sex that they were born or identify as, the way we overcome all of that – is coming together and healing across this great divide that has been created. And we do that by coming together prepared for the road ahead.” – Mainline Protestant sermon

Quotations have been lightly edited for readability.

Correction (Oct. 13, 2021): A paragraph near the top of this report has been revised to accurately reflect the dates of the data collection period used for this analysis. The correct dates for data collection for this study are Aug. 31 – Nov. 8, 2020. This correction does not affect the accompanying graphic or materially change the findings or conclusions of the report.