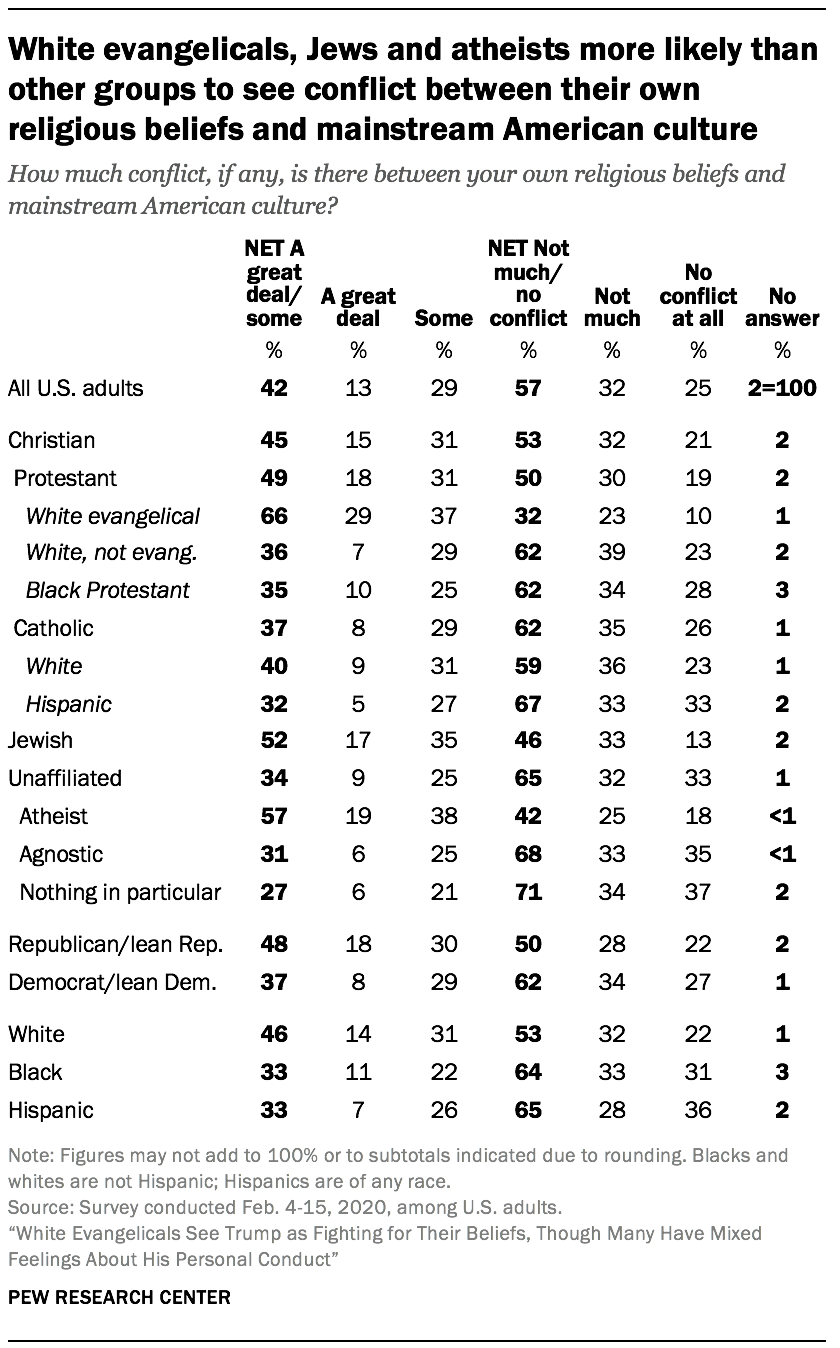

Most U.S. Christians perceive their religion as losing influence in America, and many go so far as to say that there is tension between their beliefs and the mainstream culture. These views are particularly widespread among white evangelical Protestants, two-thirds of whom see at least some conflict between their own religious beliefs and mainstream American culture.

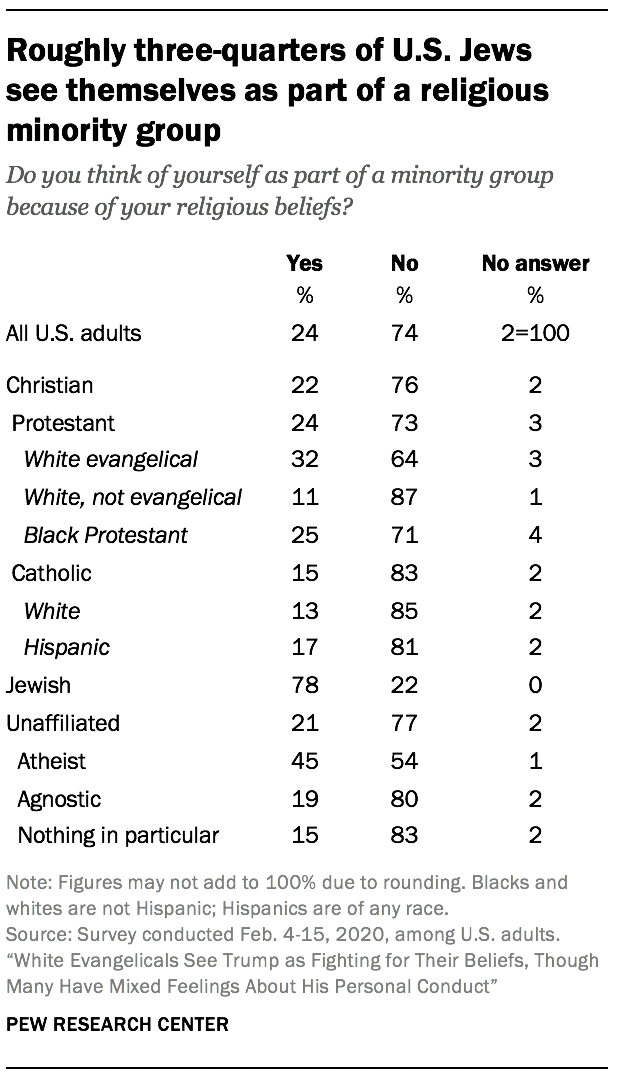

The survey also shows, however, that Christians are somewhat more likely to think their religion’s perceived decline in influence is a temporary, rather than permanent, change. In addition, just one-in-five U.S. Christians, including a third of white evangelical Protestants, see themselves as members of a minority group because of their religious beliefs. (Jews and atheists answer this question quite differently, with 78% and 45%, respectively, saying they see themselves as part of a religious minority group.)

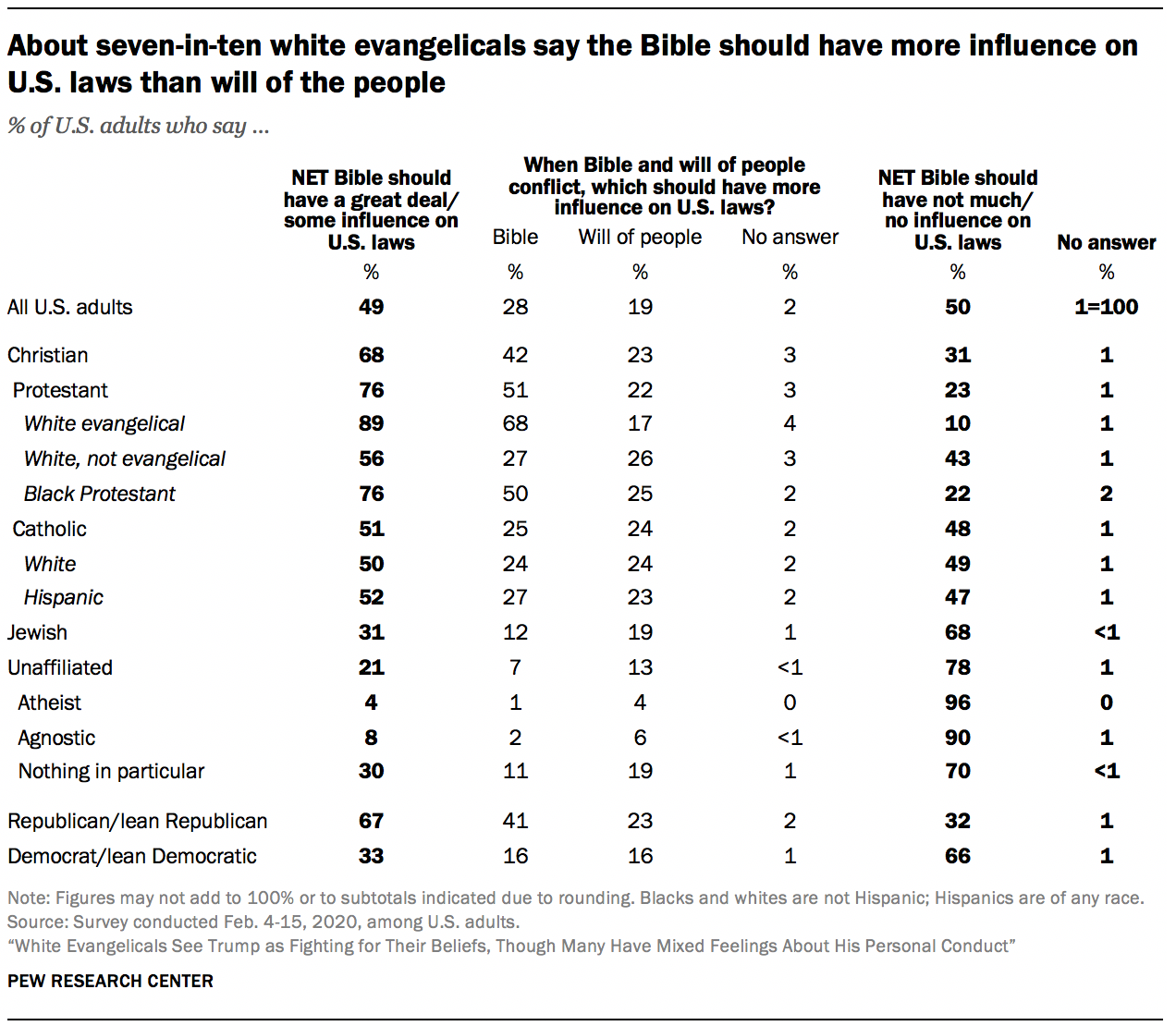

The study also finds that the public is divided over how much influence the Bible should have on U.S. laws. Half of U.S. adults say it should have “a great deal” or “some” influence – with 28% going on to say that the Bible should take precedence over the will of the people – while the other half want little or no biblical influence on the laws of the land.

The rest of this chapter explores these and other questions in more detail.

Four-in-ten Americans perceive conflict between their religious beliefs and mainstream culture; fewer think of themselves as part of a religious minority group

Four-in-ten U.S. adults say there is at least some conflict between their own religious beliefs and mainstream American culture, including 13% who say there is “a great deal” of conflict and 29% who see “some” conflict between their values and the prevailing culture.

Four-in-ten U.S. adults say there is at least some conflict between their own religious beliefs and mainstream American culture, including 13% who say there is “a great deal” of conflict and 29% who see “some” conflict between their values and the prevailing culture.

The perceived disconnect between personal religious beliefs and mainstream culture peaks among white evangelical Protestants, 66% of whom say there is at least some conflict between their own religious beliefs and the prevailing culture – including three-in-ten who feel “a great deal” of conflict. But white evangelicals are not alone in this perception; about six-in-ten atheists and roughly half of Jews also say their own religious beliefs conflict at least “some” with mainstream American culture.

Roughly half of Republicans and those who lean toward the Republican Party see at least “some” conflict between their own religious beliefs and mainstream American culture (48%), higher than the 37% of Democrats and Democratic leaners who say the same. And white respondents are more likely than those who are black or Hispanic to perceive a conflict between their own beliefs and the broader culture (46% of white respondents vs. 33% each for black and Hispanic respondents).

Roughly half of Republicans and those who lean toward the Republican Party see at least “some” conflict between their own religious beliefs and mainstream American culture (48%), higher than the 37% of Democrats and Democratic leaners who say the same. And white respondents are more likely than those who are black or Hispanic to perceive a conflict between their own beliefs and the broader culture (46% of white respondents vs. 33% each for black and Hispanic respondents).

About three-quarters of U.S. Jews (who make up roughly 2% of U.S. adults) say they think of themselves as part of a minority group because of their religious beliefs, as do 45% of self-described atheists (who account for roughly 4% of the U.S. adult population). Across all Christian traditions analyzed, one-third or fewer say they think of themselves as part of a minority group because of their religious beliefs.

Among U.S. adults, no consensus on whether Christianity’s declining influence is temporary or permanent

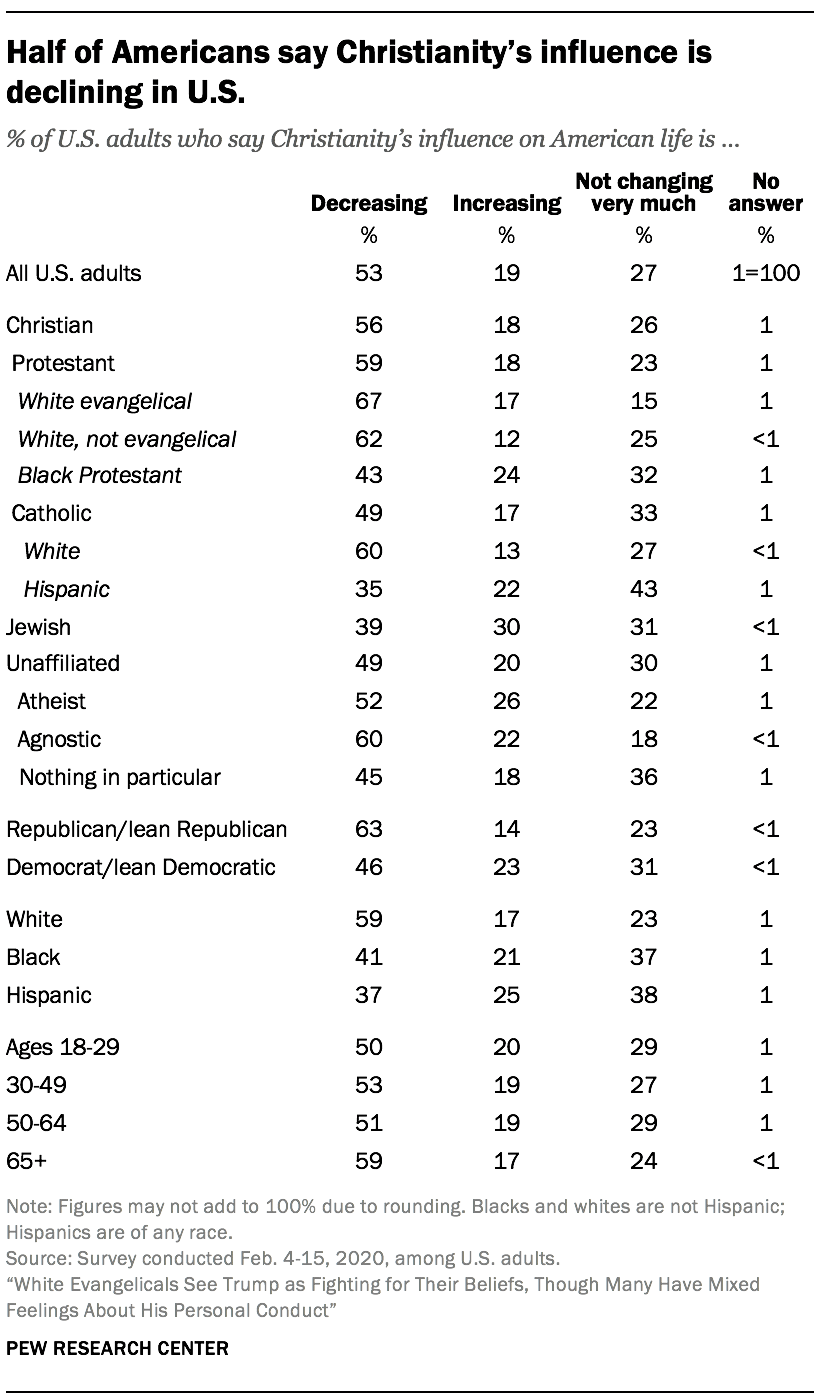

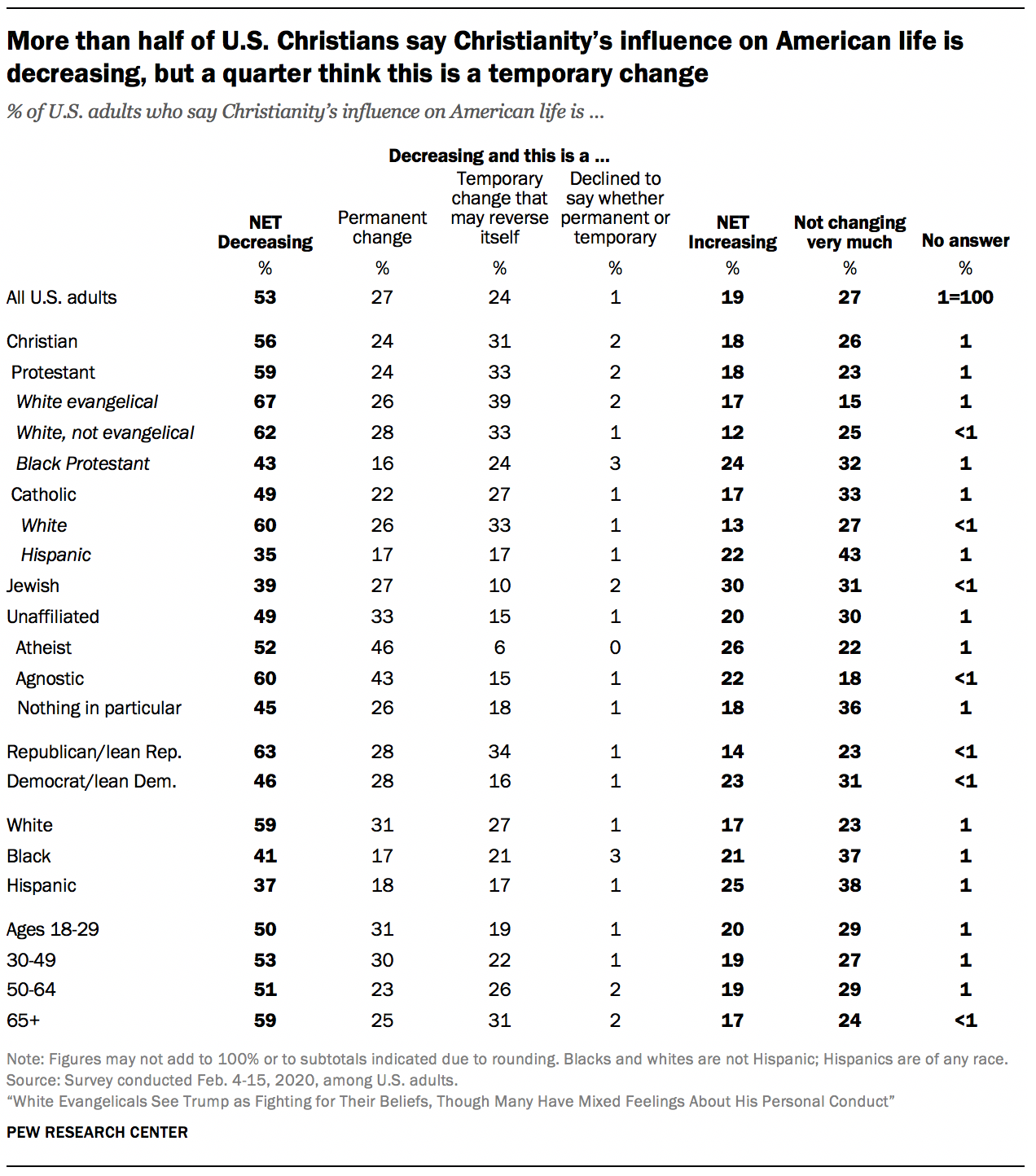

About half of U.S. adults say Christianity’s influence on American life is decreasing (53%), while one-in-five say Christianity’s influence is growing and 27% say Christianity’s level of influence in American life is not changing very much. The view that Christianity’s influence is declining is more common among white respondents than among black and Hispanic adults, and it is more common among Republicans and those who lean toward the GOP than among Democrats (though a plurality of Democrats agree with most Republicans that Christianity’s influence is waning).

About half of U.S. adults say Christianity’s influence on American life is decreasing (53%), while one-in-five say Christianity’s influence is growing and 27% say Christianity’s level of influence in American life is not changing very much. The view that Christianity’s influence is declining is more common among white respondents than among black and Hispanic adults, and it is more common among Republicans and those who lean toward the GOP than among Democrats (though a plurality of Democrats agree with most Republicans that Christianity’s influence is waning).

U.S. adults are about evenly divided between those who see the decline of Christianity’s influence as permanent and those who see it as potentially fleeting: 27% of U.S. adults say Christianity’s influence is decreasing and that this is a permanent change, while 24% say Christianity’s influence is waning but that this is a temporary development that may reverse itself.

Christians are somewhat more likely to see their religion’s declining influence as temporary than they are to see it as a permanent decline (31% vs. 24%). By contrast, Jews and religious “nones” tend to think Christianity’s declining influence will be permanent.

The survey also shows that a larger share of Republicans than Democrats see Christianity’s loss of influence as a temporary development. And the oldest Americans (ages 65 and older) are more inclined than younger adults to believe that Christianity’s decline will prove to be a blip rather than a lasting change.

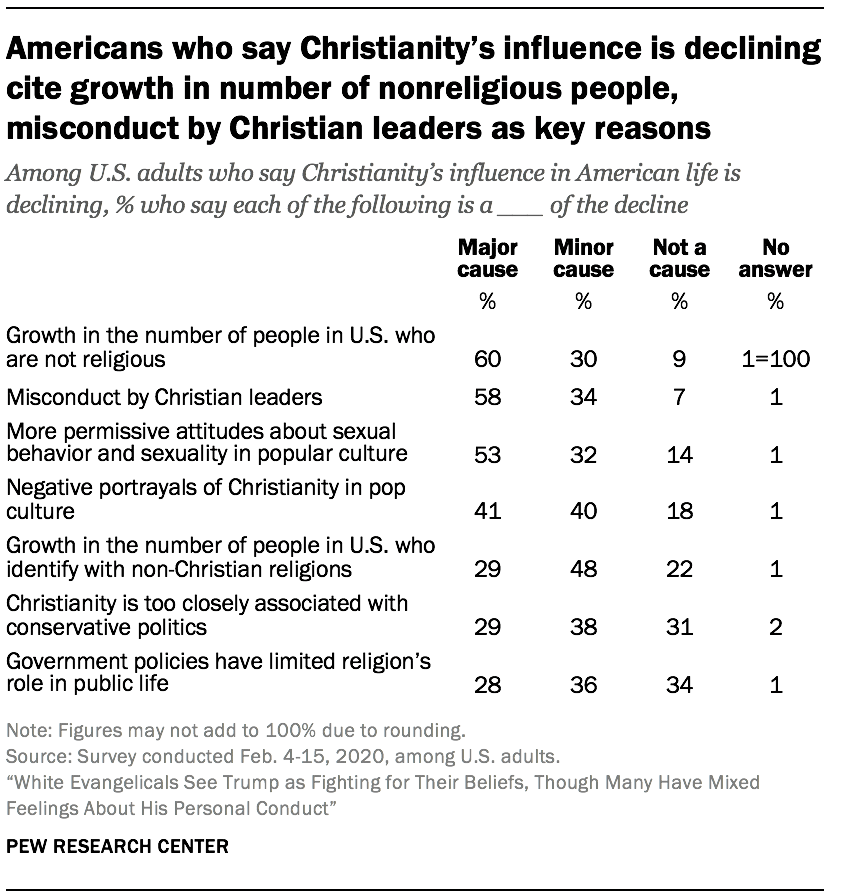

The survey also asked respondents who think Christianity’s influence is declining to assess whether each of a variety of factors has been a major cause, minor cause, or not a cause of the decline. Overall, six-in-ten people who think Christianity’s influence is waning say that growth in the number of people in the U.S. who are not religious is a “major cause” of the change, and a similar share (58%) blame misconduct by ministers, priests or other Christian leaders.

About half of those who say Christianity’s influence is declining cite more permissive attitudes about sex and sexuality in popular culture as a major cause, and four-in-ten say negative portrayals of Christianity in pop culture have played a key role. Roughly three-in-ten say growth in the number of adherents of non-Christian faiths, the association of Christianity with conservative politics, or government policies limiting religion’s role in public life have been major causes of Christianity’s waning influence.

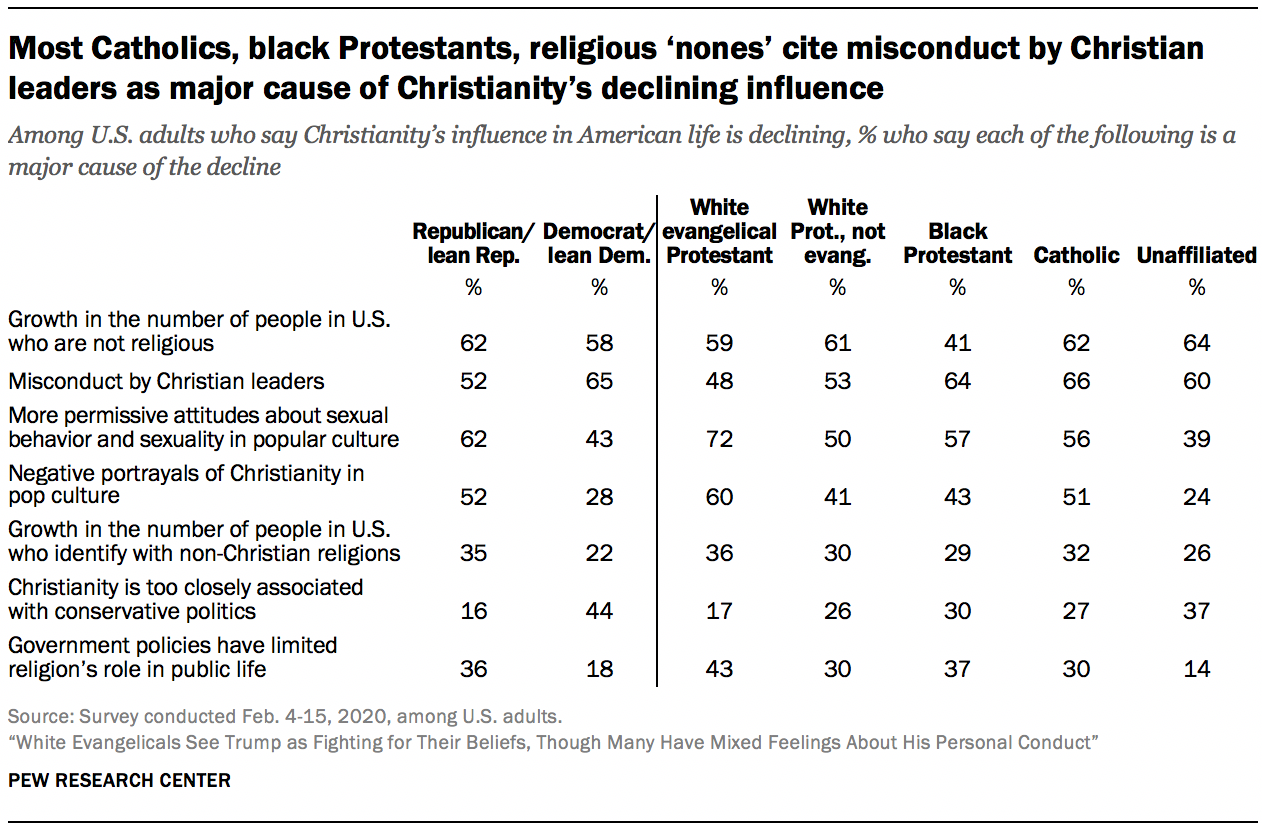

Compared with other Christian groups and especially with religious “nones,” white evangelical Protestants who say Christianity’s influence is declining are more inclined to blame this on society’s changing standards relating to sex and sexuality and on negative portrayals of Christianity in popular culture. By contrast, Catholics and black Protestants are more apt than white evangelicals to attribute Christianity’s declining influence to misconduct by ministers, priests and other religious leaders.

Compared with other Christian groups and especially with religious “nones,” white evangelical Protestants who say Christianity’s influence is declining are more inclined to blame this on society’s changing standards relating to sex and sexuality and on negative portrayals of Christianity in popular culture. By contrast, Catholics and black Protestants are more apt than white evangelicals to attribute Christianity’s declining influence to misconduct by ministers, priests and other religious leaders.

There also are significant partisan divisions regarding the cause of Christianity’s perceived loss of influence. Two-thirds of Democrats who say Christianity’s influence is declining (65%) cite misconduct by religious leaders as a major cause, compared with 52% of Republicans who say this. Democrats also are more likely than Republicans to see Christianity’s association with conservative politics as a major cause of its loss of influence. By contrast, Republicans are much more likely than Democrats to cite changing norms about sexuality as a major cause of Christianity’s declining influence (62% vs. 43%). Republicans also are more likely than Democrats to view negative portrayals of Christianity in pop culture (52% vs. 28%), growth in the number of adherents of non-Christian religions (35% vs. 22%), and government policies limiting religion’s role in public life (36% vs. 18%) as major causes of Christianity’s declining influence.

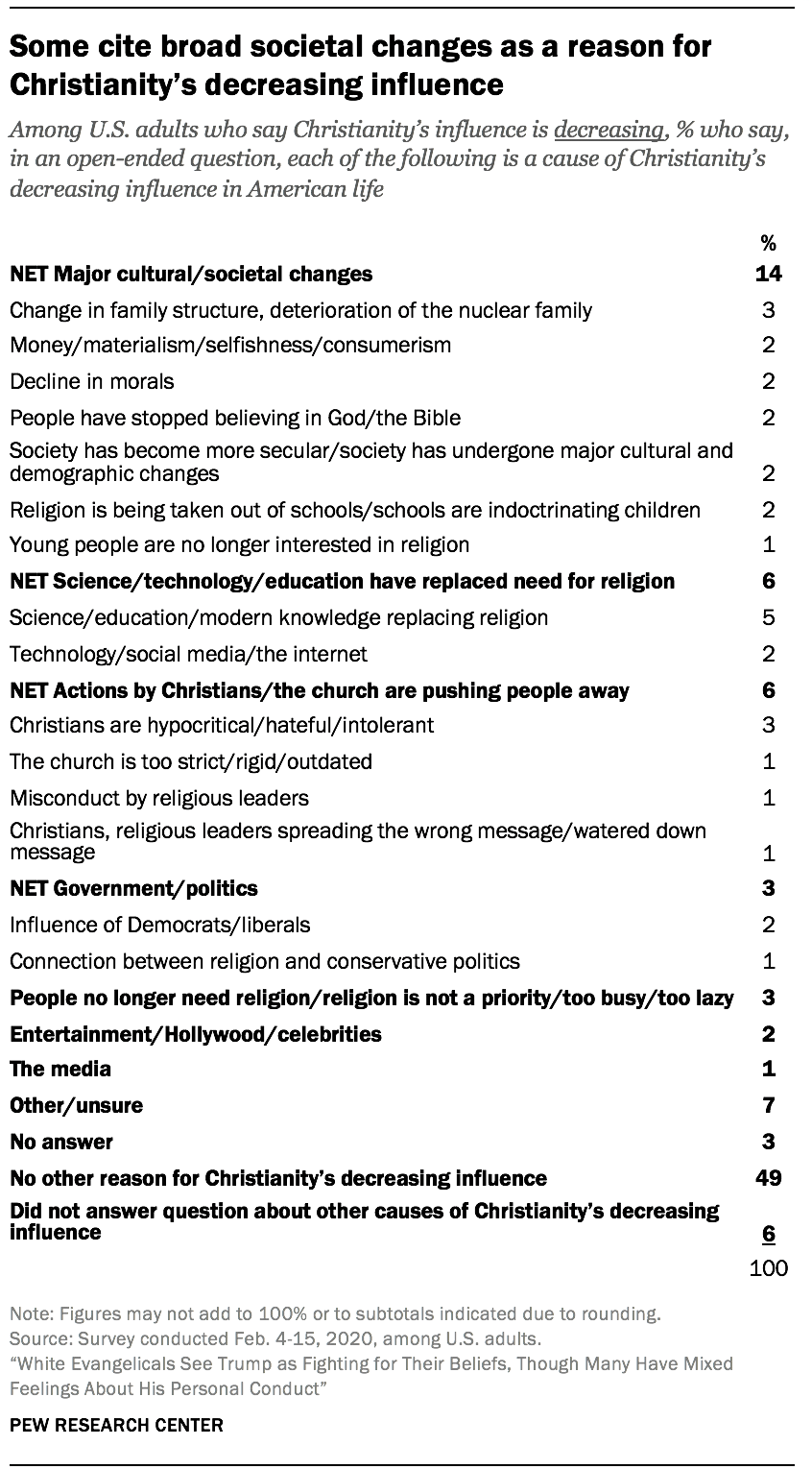

Respondents who say Christianity’s influence is decreasing also received an open-ended question (in addition to the questions about specific possible reasons): Are there any other reasons for Christianity’s waning influence? Just under half of respondents offered an answer, and the responses covered a wide array of topics.

Respondents who say Christianity’s influence is decreasing also received an open-ended question (in addition to the questions about specific possible reasons): Are there any other reasons for Christianity’s waning influence? Just under half of respondents offered an answer, and the responses covered a wide array of topics.

The most common type of response involves large-scale societal and cultural changes happening in the U.S. (14%). This includes mentions of changes in family structure (3%), a general decline in morals in the U.S. (2%) and religion being taken out of schools (2%) as reasons for Christianity’s declining influence.

Some respondents also give answers about advances in science and technology and increased educational attainment contributing to a decreased need for religion (6%). The same share cite negative actions by Christians and religious leaders as contributing to pushing people away from Christianity (6%).

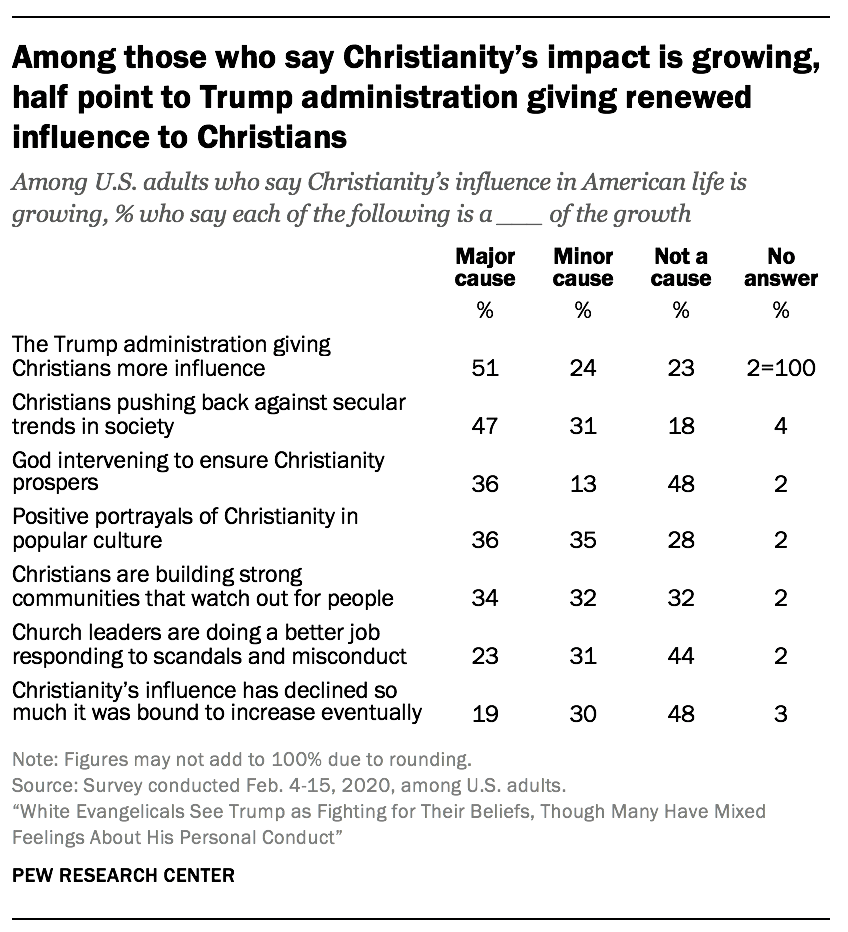

Fewer Americans say Christianity’s influence is increasing, but these respondents also were asked about several possible reasons for this perceived trend. Half of those who say Christianity’s influence is growing see the Trump administration giving Christians more influence as a “major cause” of the change (51%), and a similar share cite Christians’ efforts to push back against secular trends in society (47%).

Fewer Americans say Christianity’s influence is increasing, but these respondents also were asked about several possible reasons for this perceived trend. Half of those who say Christianity’s influence is growing see the Trump administration giving Christians more influence as a “major cause” of the change (51%), and a similar share cite Christians’ efforts to push back against secular trends in society (47%).

Roughly one-in-three cite God’s intervention, positive portrayals of Christianity in popular culture, and Christians’ efforts to build communities of people who watch out for one another as major causes of Christianity’s growing influence. One-in-four Americans who think Christianity’s influence is growing (23%) say that improvements in the way Christian leaders have responded to scandals and misconduct are a major cause of Christianity’s increasing influence, while one-in-five say Christianity’s influence has declined so much that a rebound was inevitable (19%).

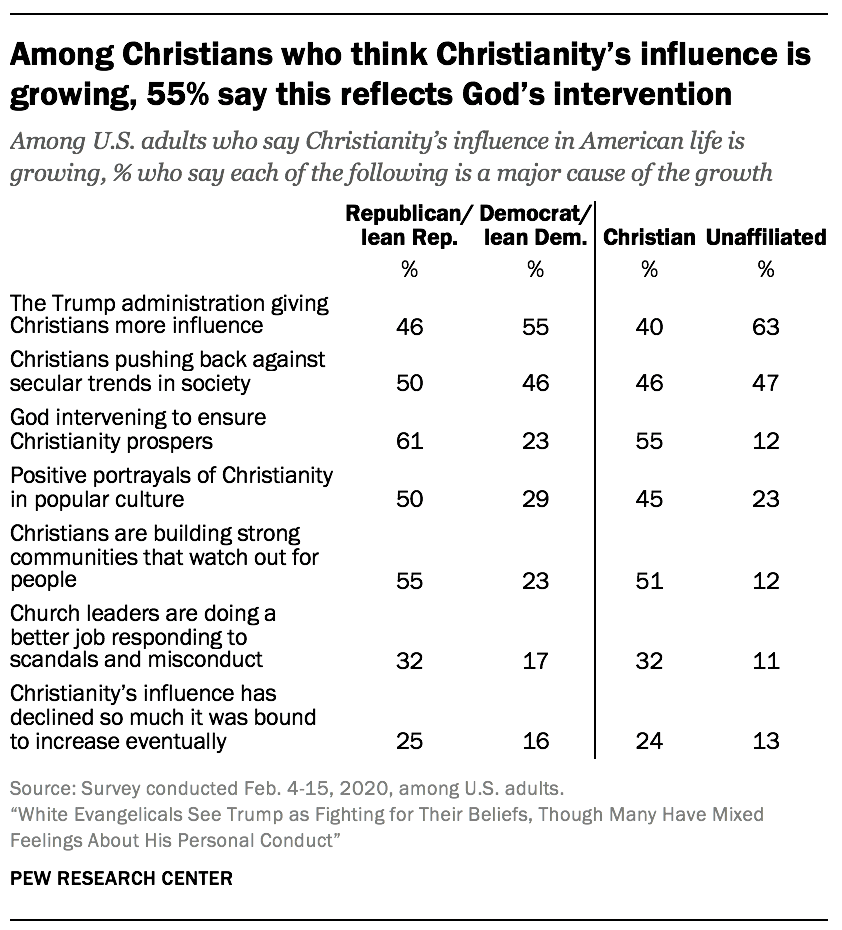

Among religious “nones” who think Christianity’s influence in American life is growing, 63% chalk this up to the actions of the Trump administration, compared with 40% of Christians who say this. By contrast, 55% of Christians who think Christianity’s influence is growing see God’s intervention as a major cause, and 51% say this about Christians’ efforts to build strong communities. Just one-in-ten religious “nones” take these positions. Christians also are more apt than religious “nones” to cite positive portrayals of Christianity in pop culture, improved reactions to clerical scandals and misconduct, and an inevitable reversal after a decline as key factors in what they perceive as Christianity’s resurgent influence.

Among religious “nones” who think Christianity’s influence in American life is growing, 63% chalk this up to the actions of the Trump administration, compared with 40% of Christians who say this. By contrast, 55% of Christians who think Christianity’s influence is growing see God’s intervention as a major cause, and 51% say this about Christians’ efforts to build strong communities. Just one-in-ten religious “nones” take these positions. Christians also are more apt than religious “nones” to cite positive portrayals of Christianity in pop culture, improved reactions to clerical scandals and misconduct, and an inevitable reversal after a decline as key factors in what they perceive as Christianity’s resurgent influence.

Among those who say Christianity’s influence is growing, Democrats are more likely than Republicans to cite the Trump administration as a major cause of Christianity’s growing influence. Otherwise, Republicans are more inclined than Democrats to say most of the factors asked about in the survey are “major causes” of Christianity’s renewed influence in American life.

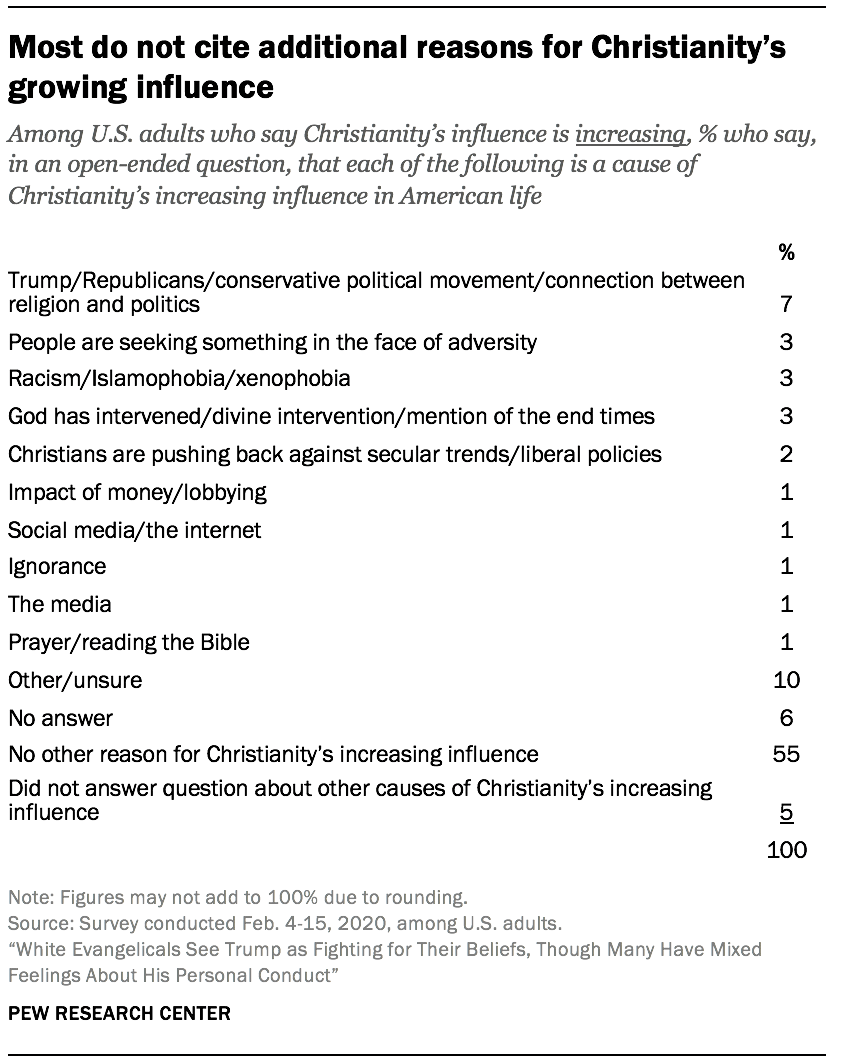

In response to an open-ended question asking about any other reasons why Christianity’s influence is increasing in American life, respondents with this perspective most commonly mention the Trump administration and the connection between religion and politics in the U.S. (7%).

In response to an open-ended question asking about any other reasons why Christianity’s influence is increasing in American life, respondents with this perspective most commonly mention the Trump administration and the connection between religion and politics in the U.S. (7%).

Another 3% say that Christianity’s growth is due to people seeking comfort and hope in the face of adversity or uncertainty, while similarly small shares mention racism and xenophobia (3%) or the intervention of God (3%). Just over half of people who see Christianity’s influence as increasing (55%) do not cite another reason for this trend (in addition to those specifically measured by the survey).

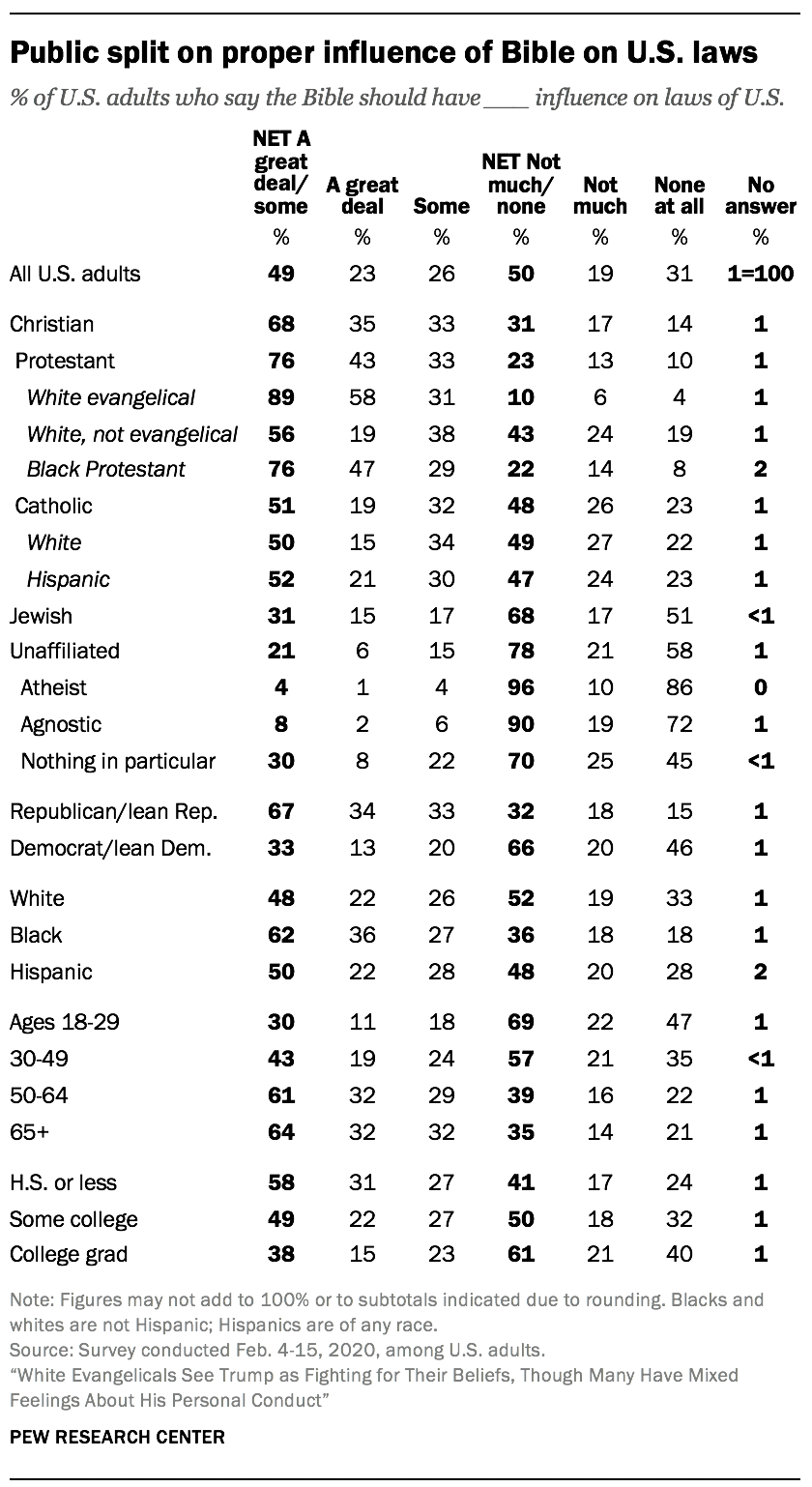

Half say Bible should have a great deal or some influence on U.S. laws

Half of U.S. adults say the Bible should have “a great deal” or “some” influence on the country’s laws. This view is most common among white evangelical Protestants (89%) and black Protestants (76%). More than half of white Protestants who do not self-identify as born-again or evangelical Christians also want the Bible to have at least “some” influence on U.S. laws, though people in this group are much less inclined than white evangelicals or black Protestants to say the Bible should have “a great deal” of influence. Catholics are evenly divided on this question; half say the Bible should have at least some influence on U.S. laws, while the other half say the Bible should have little or no influence on American laws.

Half of U.S. adults say the Bible should have “a great deal” or “some” influence on the country’s laws. This view is most common among white evangelical Protestants (89%) and black Protestants (76%). More than half of white Protestants who do not self-identify as born-again or evangelical Christians also want the Bible to have at least “some” influence on U.S. laws, though people in this group are much less inclined than white evangelicals or black Protestants to say the Bible should have “a great deal” of influence. Catholics are evenly divided on this question; half say the Bible should have at least some influence on U.S. laws, while the other half say the Bible should have little or no influence on American laws.

Eight-in-ten religious “nones,” including 96% of self-described atheists and 90% of agnostics, say the Bible should have little or no influence on U.S. laws. And about seven-in-ten Jewish respondents want little or no biblical influence on the country’s laws.

The survey shows that Republicans and Democrats are mirror images of each other on this question. Two-thirds of Republicans and those who lean toward the GOP say the Bible should have “a great deal” or “some” influence on the country’s laws. By contrast, two-thirds of Democrats say the Bible should not have much, if any, influence on U.S. laws.

There are twice as many Americans ages 65 and older who want the Bible to have an influence on the laws of the land as there are among adults under 30 (64% vs. 30%). And Americans with a high school degree or less education are much more inclined than college graduates to say the Bible should influence U.S. laws (58% vs. 38%).

Respondents who said they think the Bible should have at least “some” influence on U.S. laws were asked a hypothetical follow-up question: When the Bible and the will of the people conflict with each other, which should have more influence on the laws of the United States?

Overall, three-in-ten U.S. adults say they think the Bible should have more influence on the laws of the land in cases where the Bible and the will of the people conflict. This view is most commonly held by white evangelical Protestants, among whom about seven-in-ten say that when the Bible and the will of the people conflict, the Bible should be more influential. Half of black Protestants share this view. Majorities in all other religious groups in this analysis say either that the Bible should have little or no influence on U.S. laws or that it should be subordinate to the will of the people.

Four-in-ten Republicans and Republican leaners say they think that when the Bible and the will of the people conflict, the Bible should have more influence on U.S. laws, while 16% of Democrats share this view.